Everything That Happens in Red Desert (8)

The cloud of steam

In this post, I will slightly disrupt the chronology of the film by discussing the final part of the ‘factory tour’ sequence, when Ugo and Corrado spectate a billowing cloud of steam in a courtyard. Part 9 will focus on the scene just before this, when Ugo, Corrado, and Giuliana meet inside the factory.

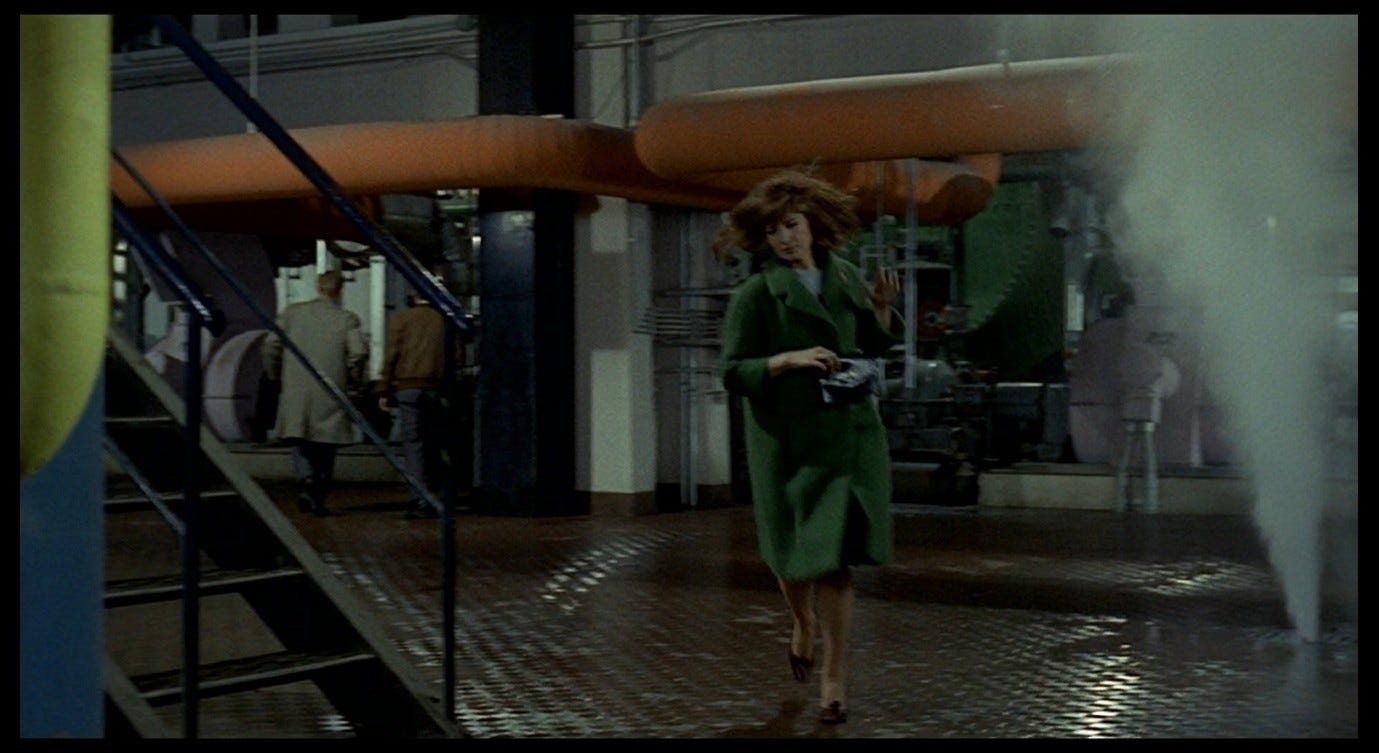

The enormous steam-cloud is the culmination of a series of ventilations throughout these early scenes of Red Desert. It is worth taking stock of how this motif has manifested itself up to this point. We begin, in the title sequence and the first scene, with the clouds of smoke and jets of flame pouring or bursting from the factories, and we also see steam and smoke rising from the slag-heap. Inside the factory, we hear the exchange between Ugo and his colleague about the over-heated vapour, and we see Giuliana alarmed (as she arrives) by the ventilator blowing her hair and (as she leaves) by the steam shooting up from the floor.

Now, we see a vast cloud of steam that envelops an entire courtyard, filling the frame and the soundtrack, before dissipating again.

The flames, steam, smoke, and wind that characterise the industrial world in Red Desert carry various connotations. On the one hand, they represent control and moderation, but on the other hand they are spasmodic and unpredictable. Like the mechanical eye that stares through the ceiling, these industrial phenomena are both purposeful and mysterious, controlled and menacing.

The steam-cloud episode brings this motif to an apocalyptic climax. It is a breathtaking set-piece that suspends the action of the film. The two men come to a halt for no apparent reason, and gradually we realise that Ugo has brought Corrado here with the express purpose of showing him this phenomenon. He commentates the spectacle, presumably explaining what is happening, but all we see and hear is the steam. Deprived of any rational explanation, how do we respond to this? Let’s break the sequence down shot-by-shot.

First, we see the steam-cloud’s origin, a ventilator in a wall that begins by oozing steam and then suddenly sprays huge quantities of it in our direction.

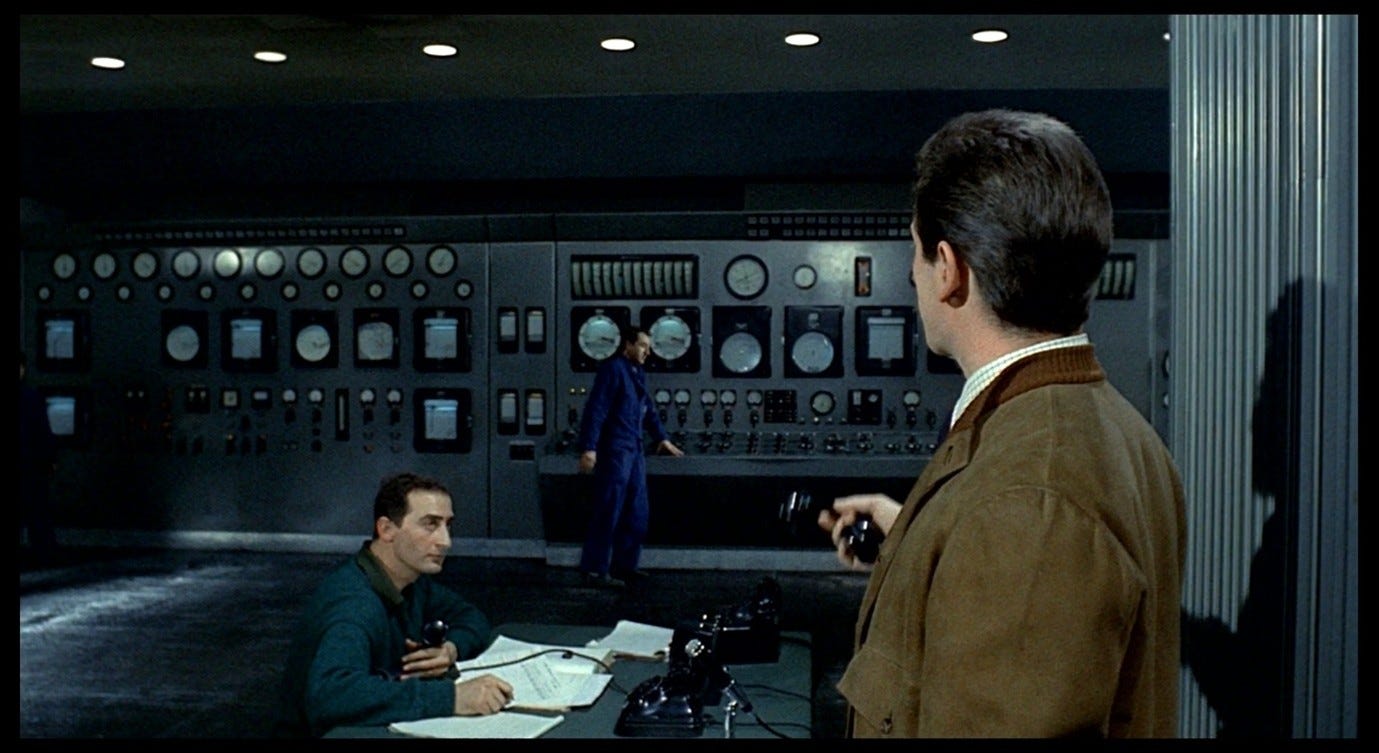

It is a slightly shocking moment; at first we do not know whether this explosion is an accident or a routine safety measure, but it soon becomes obvious that it is the latter. When we first met Ugo, an employee was telling him that ‘The temperature of the steam [vapore] is high,’ and he responded, ‘Lower the burners [bruciatori] a little.’ In Italian, that exchange has (to my ears) a kind of poetry to it, and there is certainly a performative swagger in the way Ugo disposes of the problem and then turns to resume his conversation with Corrado.

Perhaps, for the finale of the factory tour, he has brought Corrado here to illustrate the through-line from the control room to the outdoor steam-vent. Ugo knows when to lower the burners, and he knows when and where the vapore is due to be vented in the courtyard, so he can time his and Corrado’s arrival at this scene with casual precision.

The vapour-spray overwhelms the frame – we are too close to the vent – so the camera moves to a better vantage-point to capture the growing cloud. Ugo and Corrado also move to a better vantage-point.

Then the camera steps even further back, as the cloud grows bigger still and the two men settle on an optimal viewing position.

For the moment, the camera prioritises clarity: it shows us where the steam-cloud comes from, then it makes sure that we can see as much of it as possible. This suggests that we are supposed to comprehend what we are watching, to see clearly what Ugo is pointing at and to understand what it is. But being far enough away to see the entire cloud means being too far away to hear Ugo. As in the floor-grate shot discussed in Part 7, we find ourselves looking with the eyes of a creature that neither wants nor needs to hear human voices, or to have things explained to it. It just wants to watch.

After watching Ugo and Corrado watching the steam, we cut to the reverse angle, from across the courtyard, and the two men are rapidly eclipsed.

Ugo and Corrado remain absent in the next shot, which returns to the other side of the courtyard but looks from a lower angle, to see how high the cloud is rising.

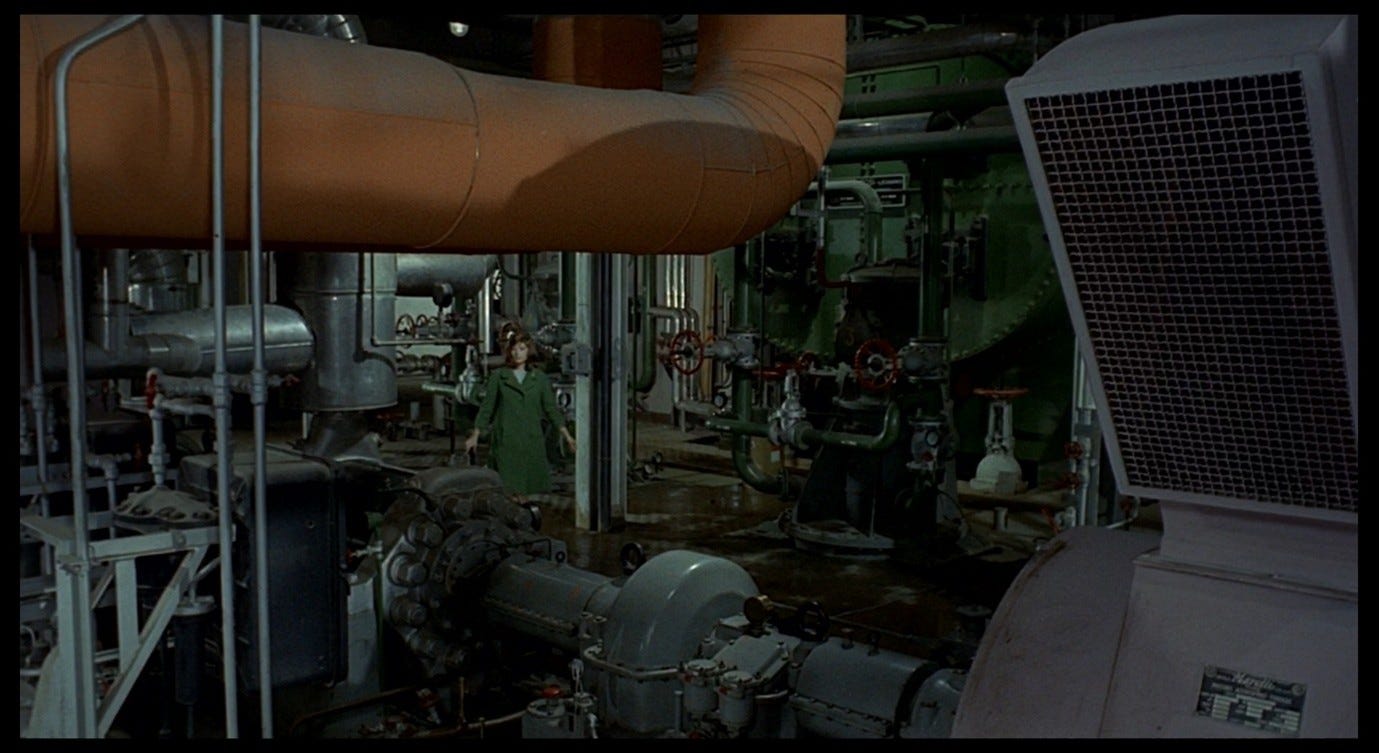

Disappearing people are one of Antonioni’s favourite motifs, and this sequence illustrates two ways of making them disappear: by covering them with fog or by letting the camera drift away from them as though distracted. People can be eclipsed by larger forces or they can simply become less interesting than their surroundings. This phenomenon needs to be captured from a distance to understand its shape and scale, but it also needs to be captured up close, so close that (for the moment) we forget everything else.

However, we then leave the cloud behind entirely to watch Ugo yelling into Corrado’s ear.

There is a dramatic contrast between the cloud-covered environment in the previous shots and the void behind Ugo and Corrado here. The yard extends for a long way and the buildings loom impressively on all sides. It is one of many images in this film that show the overwhelming scale of the industrial landscape. However, the space has visible limits and it is completely empty. We are in Ugo’s world – a world he understands and can explain – and not a single wisp of the unruly steam-cloud can intrude upon it without his authorisation, nor (for the moment) can anyone else occupy it. Ugo floods one courtyard with steam but he clears another for himself and his guest. His power is expressed through the ability to conjure both plenitude and emptiness.

There is another dramatic contrast in the next shot, between the two men’s smallness and stillness (as we see them from behind, at a greater distance than ever) and the pounding momentum with which the cloud expands in front of them.

How can these men feel safe, standing so close to this explosion? The roiling of the cloud is so fierce that it seems on the verge of breaking all limits and consuming everything around it. But just as Ugo can explain this phenomenon with ease, so he also knows its exact parameters. He has chosen a spot that will bring him and Corrado close enough to observe the ventilation process, while keeping them at a safe distance.

Then there is another low-angle shot of the steam-cloud eclipsing the sky.

As the screenplay puts it, the cloud covers not only the factory buildings but even the ‘grey light of the sky.’1 Grey skies overshadow all the daytime scenes in Red Desert: in this film there is a perpetual cloud above us, eclipsing and filtering the sunlight. Antonioni explained this by comparing his approach to that of a painter:

Let’s suppose we have a blue sky. Who knows if it’s going to work; or, if I don’t need it, where can I put it? So I pick a gray day for a neutral background, where I can insert all the color elements I need – a tree, a house, a ship, a car, a telegraph pole. It’s like having a white paper on which to apply colors.2

Using a grey sky as a blank canvas on which to apply a white cloud is a slightly mind-bending choice for a visual artist, like the black-and-grey combinations of the Rothko Chapel.3

The Red Desert steam-cloud is so prevalent, so ‘eclipsing’, that the next shot feels like an interior view of a warehouse, though in fact we are in the same outdoor space where we saw the barrels lined up a moment earlier. Only the overhead cables, which remain stubbornly visible, remind us that we are still outside. The camera tilts upwards and the cloud takes over the world again.

Finally, we see the cloud retreating behind a wall, as Ugo and Corrado (still tiny) calmly walk away from it.

The whine of the factories has been replaced by a hissing white noise throughout the steam-cloud sequence, a noise so intense that Corrado occasionally has to cover his ears. Now, as the cloud recedes, the familiar factory songs fade in again.

The camera shows us this spectacle from several different angles in order to record it accurately and comprehensively. Perhaps Antonioni has discovered a real-life industrial phenomenon and is so impressed by it that he wants to capture it as fully as possible: there is a sense of enthusiasm, or even a slightly muted joy, in the way the camera jumps around from one set-up to another. Alternatively, the scene may spring from the director’s own imagination, and the steam-cloud may be completely staged. The lack of explanation leaves the sequence balanced on a knife-edge between documentary and fiction. It leaves us in a similar position to that of Giuliana when she faces such manifestations: unsure whether this is reality or fantasy, unable to define our relation to it. We experience the industrial process intimately, through the inquisitive and fearless eye of the camera, but our own reaction does not have to be inquisitive or fearless. In place of Ugo’s explanation, we hear only the noise of the process itself. Left unmoored and without guidance, we may feel that we have been plunged into something against our will, and that these sights and sounds are not necessarily welcome to us.

This sequence therefore serves as a fitting summation of the factory tour. We experience this setting and are left to reflect on how we have processed (or should process) our experience. As Antonioni said several times, the film centres on the question of how we adapt to a changing world, and what happens to someone like Giuliana who finds she cannot adapt:

Man has only one alternative. Either he dies, or he adapts. It’s the theme of Red Desert. The film only dealt with the theme of man adapting to a certain environment – noise from cars, air pollution – and of the psychological effects of such an adaptation process.4

Adaptation, when seen in these terms, is not necessarily about comprehending one’s environment, but about the sensory experience of inhabiting it. How do the mind and body respond to these new things – alarming soundwaves, toxic particles – that are suddenly in the air all around us? In the interview just quoted, Antonioni went on to picture a more outlandish science-fiction version of Red Desert, and to consider adaptation not only in psychological but moral terms, as a change in how people relate to each other:

But one could imagine more radical transformations, of an anthropological nature; changes in morphology, physiology, in behavioral patterns. […] [H]umans have become – perhaps not more evil, but certainly more indifferent toward their fellow human beings.5

He then gave, as an example, the treatment of mentally ill people in America who had been deprived of any care or support structures. Giuliana, of course, has been made ill by her environment – this is how she has ‘adapted’ – and it is important to place Antonioni’s two conflicting attitudes side by side. On the one hand, he is in favour of progress and bluntly says that humans must adapt or die; on the other hand, he describes the cost (for the workers and for people like Giuliana) of such progress, and is clearly not indifferent to these casualties of modernity, even if he sees such people’s demise as more or less inevitable.

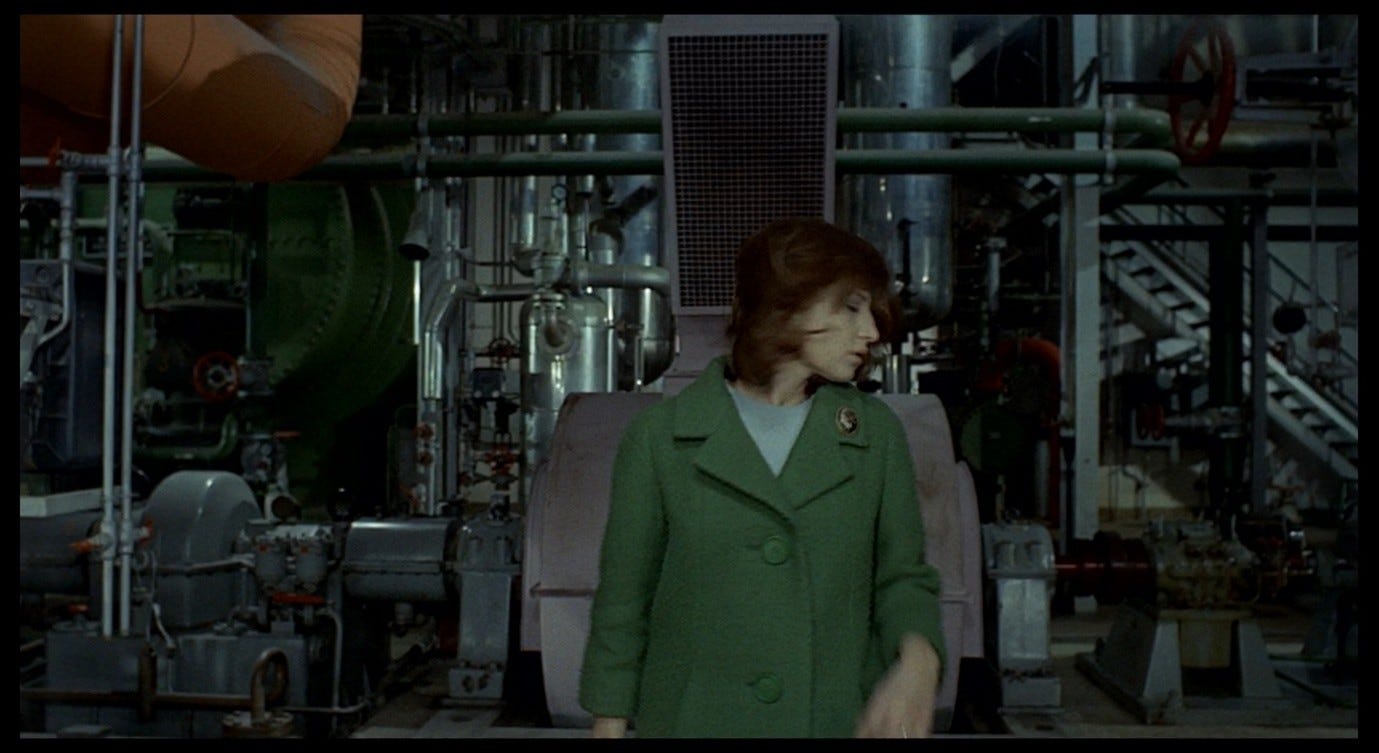

Consider how Giuliana responds to her environment in these early scenes. She was ill at ease outside the factory and is even more so inside. We see her hand recoiling from the banister as she comes down the stairs.

She is unsure of which way to go amid this labyrinth of machines.

She is disturbed to find her hair being blown out of shape by the air-vent she has accidentally stood in front of.

She is shocked by a sudden burst of steam from the floor as she leaves.

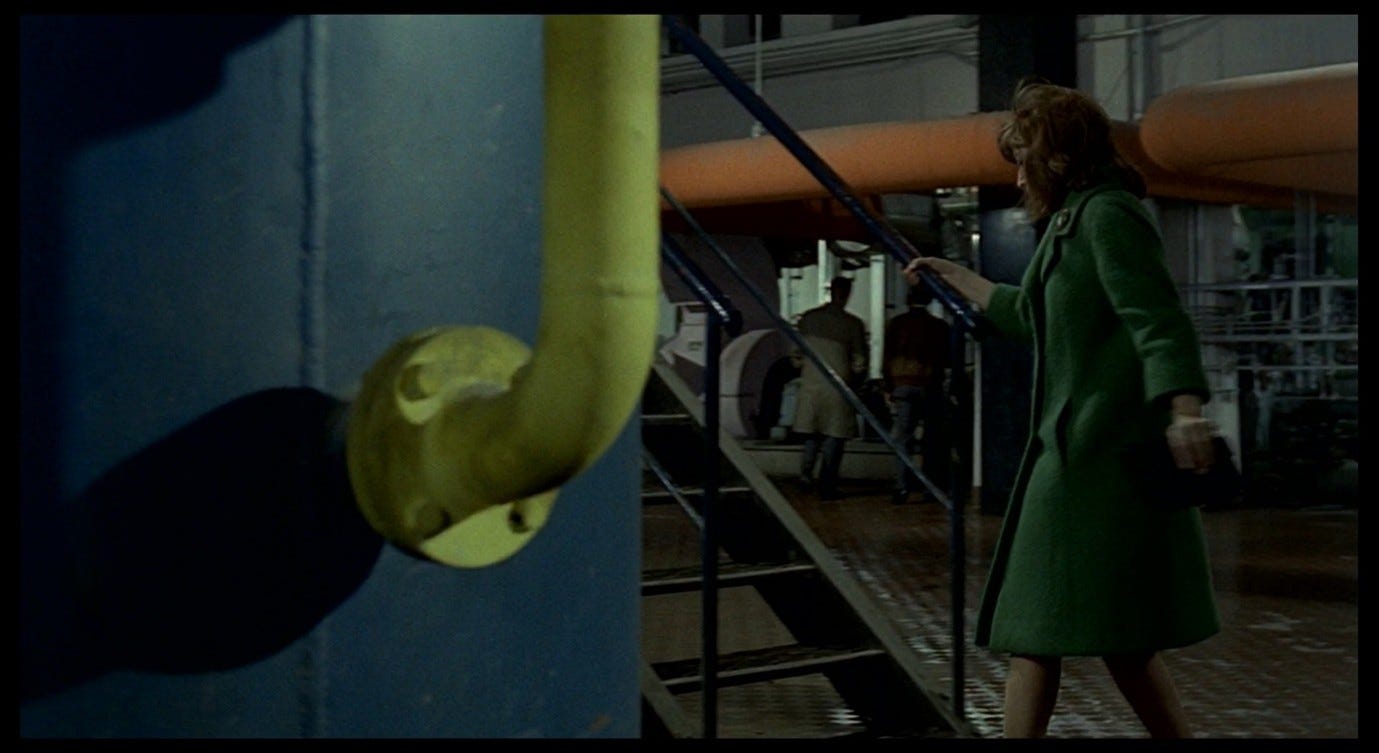

And finally, she is crowded out of the frame by the obtrusive structures around her: we pan across to a big blue tank with a yellow pipe attached, which suddenly takes over the frame as Giuliana shuffles away behind it. The blue tank seems to be saying, ‘And don’t come back!’

A few minutes later, the film will cut from the end of the steam-cloud sequence to Giuliana waking up from a nightmare, as if the steam-cloud were her nightmare, even though she is literally absent during that scene. She feels chased out of the factory yet cannot fully escape it.

John Orr observes that there is a ‘binary motif [of] hygiene and pollution’ in Red Desert, with the pristine interiors of the factory ‘connot[ing] a purity made false by the refinery’s effluent.’6 For him, the vapour-related imagery serves to dissolve the false distinctions of this binary:

[T]he size and power and noise of the complex give rise to a sense of awe and wonder, clinched in a sequence where [Ugo and Corrado] are enveloped in a massive discharge of steam which gushes out of the side of the refinery and fills the screen. Everywhere discharged vapours merge with the mists of the polluted river in telephoto shots to create a veil which blocks the power of the gaze. The swirl around the two men is a defining image, visual testimony to the power of technology and the energies it unleashes.7

Orr’s phrasing of what the steam gives ‘visual testimony to’ is obviously relevant to what the present sequence has been saying about Ugo, whose professional life is invested in ‘the power of technology and the energies it unleashes.’ Even more telling is Orr’s insistence on the commingling of power and pollution: if Ugo’s control room was disingenuously clean, a shrine to moderation belied by the steaming slag-heap outside, then this burst of steam is a more honest expression of what modern industry is about.

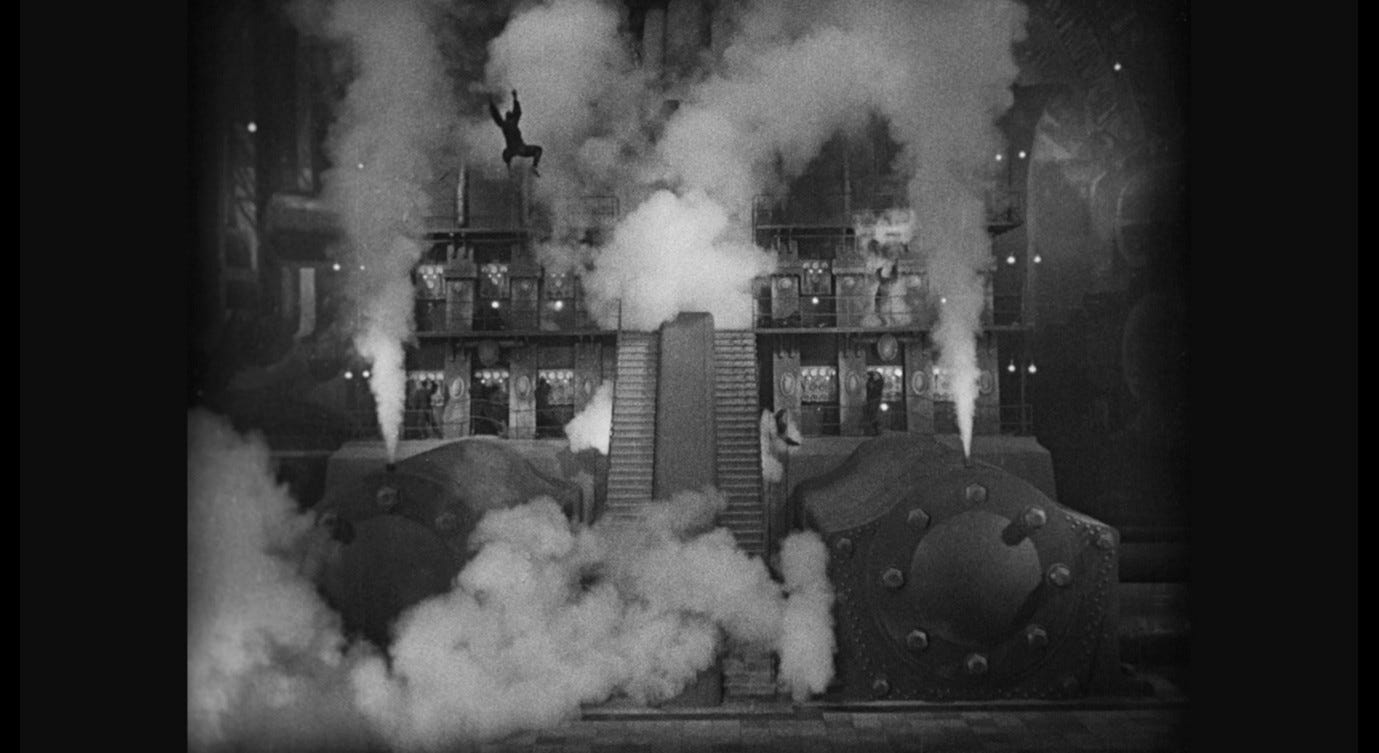

Never mind the mists and vapours that Giuliana was so transfixed by while gazing at the slag-heap; imagine what she would make of this apocalyptic beast. Where does this much energy come from, and where does it go? If this is just the excess steam that needs to be vented, what must those interior bruciatori look like? The ‘energies unleashed’ here are not only constructive but destructive: in one moment that I have always found vaguely disturbing, we see a piece of wood flying through the air in the midst of the steam-cloud, like one of the workers being flung from the Moloch-machine in Metropolis.

Ugo (like Joh Fredersen) sees productivity and control, but Giuliana (like Freder) would see a scalding explosion, poisonous mists, the sky eclipsed and the world beneath it sunk in out-of-focus obscurity. To what extent do we share Giuliana’s reactions? Do we find the steam-cloud frightening, confusing, impressive, fascinating, beautiful? Do we stand back from it and observe it with a cold, analytical eye, or do we feel ourselves and our world being consumed and destroyed by it?

In one of his early short films, Sette canne, un vestito (‘Seven reeds, one dress’), Antonioni shows the industrial process whereby reeds are transformed into rayon. As Karl Schoonover points out, there are several moments in this film where ‘steam consumes the figures of workers as in Il deserto rosso,’ or where ‘a new synthetic product empties out the image, delivering a kind of radical blankness.’8 Eugenia Paulicelli contrasts the ‘emptiness of urban space’ in other Antonioni films with the ‘volumetric dimension of nature, especially as it is expressed in Sette canne,’9 but the volume of natural materials we see here produces a visual emptiness equivalent to that of Antonioni’s urban deserts.

First, the reeds themselves fill the image to the point of obscuring everything else, and we see the workers being overwhelmed by them as they transfer them from the harvester to the trucks.

Then there is a wonderful moment when the trucks, carrying thousands of reeds, pass in front of the camera, revealing a distant factory complex as they leave the frame. We cut to a closer view of our destination which, as the narrator tells us, ‘has all the atmosphere of a mysterious castle.’ Otherworldly music plays on the soundtrack.

Perhaps Antonioni was remembering the discovery of the castle in Les visiteurs du soir, on which he had served as assistant director a few years earlier.

Once inside the factory complex, the truck passes through vast, near-empty courtyards like the one we see Ugo and Corrado standing in front of in Red Desert.

These images reinforce our sense that we are visiting a ‘mysterious castle’, a vacant, cavernous place in which magical things are accomplished in the shadows. Twice, the narrator will refer to an industrial process as a ‘miracle’, and although the documentary is clearly intended to acknowledge the workers’ efforts, at times those workers seem like apprentices to the unseen sorcerer who is actually in control. Once we are inside the factory itself, we get to the moments of ‘radical blankness’ that Schoonover is referring to:

The willingness of these shots to envelop the image in total emptiness demonstrates the aesthetic logic whereby industrial forms bring the abstract, non-figurative and excessive to the image. […] This industrial fog not only erases the human form, smothering out our ability to see the workings of a human agency, it also banishes any informational aspects of the image.10

The reeds are boiled in a vat whose steam obliterates the worker who is feeding it.

Soon after this, there is a shot that directly anticipates the shot of the steam-producing vent in Red Desert, as the boiling liquid is transferred from one vat to another. What starts as a trickle of white liquid quickly becomes a cloud of steam that takes over the whole frame.

Then we see another worker strolling into the clouds that emerge from these larger vats.

But as Schoonover says, the most extraordinary part of the documentary is when the liquid distilled from the reeds is made solid again:

What we witness is more than a simple chemical reaction. […] This is the transformation of a liquid into a solid. One kingdom of materiality becomes another. Like cinema’s central illusion of moving bodies generally, there is something uncanny happening to materiality as we know it.11

For me, the most striking part of this miracle is the creation of the huge clouds of cellulose, which the narrator says is ‘soft and light like snow.’ Its appearance reminds me, not of snow, but of the sinister (and probably toxic in real life) lake of brown-yellow foam in Stalker.

In Sette canne, the snow-like cellulose is revealed in a beautiful shot that begins on a dark, dull corner of the workshop, tracks left to discover the workers dragging the cellulose out of the machinery, and then reveals an astounding stockpile of white fluff that – once again – takes over the image and extends over an impossibly large area.

It is at this moment that the narrator delivers an ecstatic encomium to ‘the genius of scientists, the power of machines [potenza di macchine], the valour of engineers [valore di tecnici], the intelligent and inexhaustible labour of workers.’ This finds an echo in John Orr’s comment about the steam in Red Desert: ‘The swirl around the two men is a defining image, visual testimony to the power of technology and the energies it unleashes.’12 Sette canne is ostensibly celebrating the miracle of turning swamp-dwelling plants into fashionable clothing: in the final moments of the film, we see women wearing beautiful rayon dresses on a catwalk.

But that paean to science, engineering, and machinery seems to be triggered not by the fashion show, but by the image of the cellulose-clouds.

Viewed as a companion piece to Red Desert, Sette canne is about the power of modern industry to flood the world and drown its inhabitants in vast quantities of matter whose basic chemical identity (solid? liquid? vapour?) is in a constant state of flux. Schoonover’s comment that ‘there is something uncanny happening to materiality as we know it’ resembles Giuliana’s comment (later in Red Desert) that ‘there is something terrible in reality, and I don’t know what it is.’ Although the documentary’s narration is informative in ways that Red Desert never is, the short film nonetheless shows Antonioni’s fondness for abstraction, for cinematic imagery that is more about the image itself than the thing ostensibly referred to. But in both films, the abstract imagery still carries implications for the material reality of the people we are watching. Sette canne is about the experience of working in a place where you find yourself and the world you live in repeatedly obliterated, made invisible by steam and inaudible by noise, subsumed by one mass-produced product or another. Your work is a nebulous, intangible wall that entraps you.

It is also worth noting Paulicelli’s observation that the process of rayon production in some ways ‘mimes the process of filming’ by showing the successive stages of collaborative work that lead to the final, performative product.13 In Parts 25 and 27, we will see how Antonioni suggests parallels between the dehumanising effects of industry in the petrochemical and cinematic contexts.

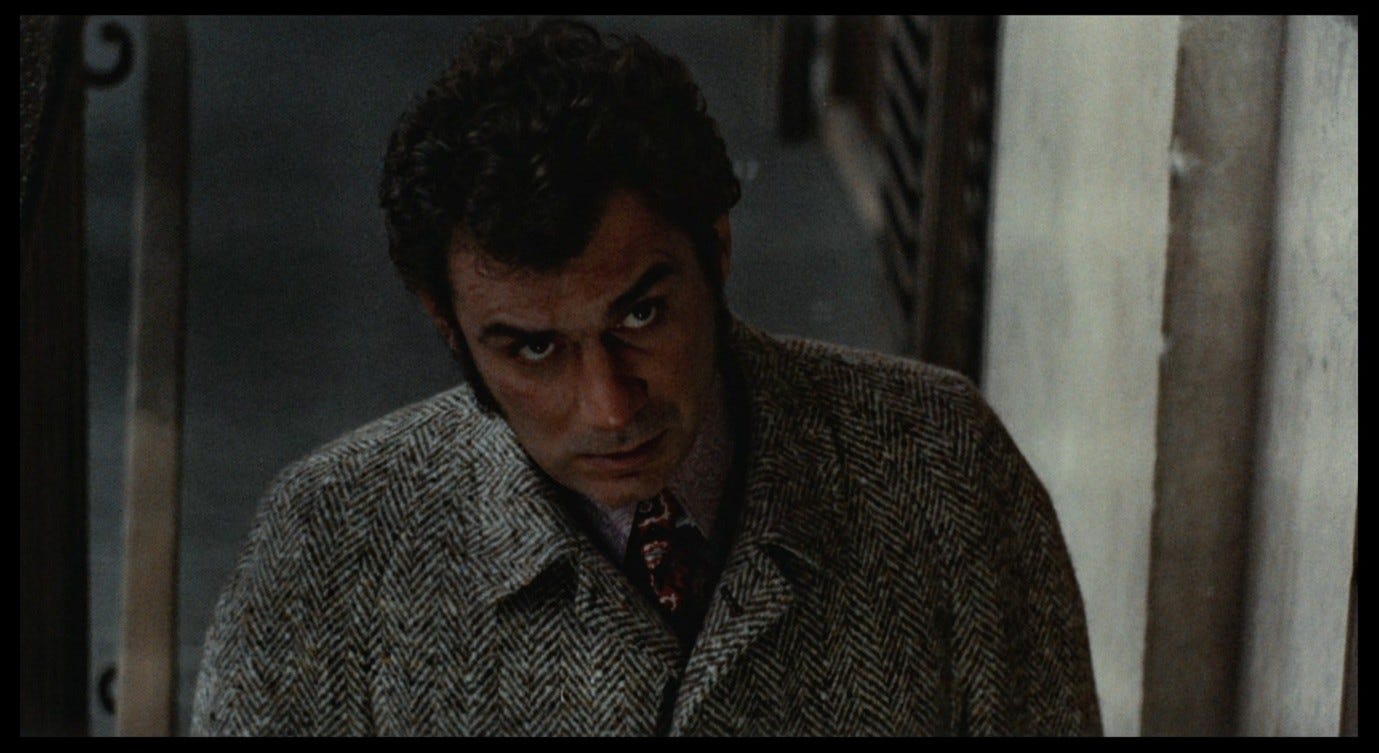

With all this in mind, we should now spend a little more time focusing on Corrado’s perspective in the steam-cloud sequence. As they approach the courtyard, he and Ugo hear two workers hammering at the top of a large red tanker.

Perhaps this is the container from which steam needs to be vented and the hammering is part of that process. Ugo immediately senses that Corrado might want to recruit these men for his project in South America, perhaps because they are evidently used to doing more perilous types of labour. But he warns Corrado off, joking that this is a ‘hunting reserve’, comparing the workers to protected wild animals. This is a tongue-in-cheek way of reminding Corrado that he is a guest in Ugo’s domain, but a moment later Corrado points to some silos in the distance and says that they were built by his father.

In some sense, this is ‘home’ to him. Ugo counters by saying that he cannot imagine Corrado, whose ambition was to be a mineral engineer, ‘alle prese con questa roba,’ literally ‘at the grips with this stuff.’ Corrado ruefully explains that since his father’s death, the business has fallen on his shoulders. Having planned to work ‘down’ (into the earth), he instead is obliged to go ‘up’ (erecting chemical plants). The ‘down’ gesture seems more confident, ‘down to earth’; the ‘up’ gesture seems ironic, as if Corrado finds the silos a little pretentious.

This conversation immediately precedes the steam-cloud spectacle. It is a crucial piece of context because when Ugo refers to ‘questa roba’ – ‘this stuff’ that Corrado shouldn’t be engaging with – he means this hunting reserve, the men who work in it, and the steam that fills it. ‘Prese’ are literally ‘grips’, and Ugo is very much ‘alle prese’ with this stuff; he has full mastery over these substances and processes, and in his comments here there is a gentle implication that Corrado may be out of his depth. From Corrado’s point of view, he is literally out of his depth, working at the wrong level and in the wrong direction. A paternal authority-figure hangs over him, keeping him in this place and thus forcing him to feel forever out of place. Corrado, like Irene Girard at the factory in Europa ’51, has to cover his ears in reaction to the unwonted noise levels.

Ugo is unperturbed by this din: he casually explains the unfurling drama to his friend, but perhaps Corrado (like us) cannot hear him, or cannot understand him. One of the important things being established here is that Corrado feels unhappy in his work, though he is resigned to pursuing it. The cloud of steam is infused with this unhappiness, as much as it is infused with the film-maker’s enthusiasm for recording a giant chemistry experiment. Corrado looks around at the factory complex that hems him in; we look around at the cloud of steam that enfolds us.

In Killer of Sheep, Stan (the titular slaughterhouse worker) feels so worn down by his job that he struggles to connect emotionally with his wife or children.

‘I’m working myself into my own hell,’ he says early in the film. ‘When I close my eyes, I can’t get no sleep at night. No peace of mind.’ Later, when he admits to a friend that he lies awake all night, the friend responds, jokingly: ‘Yeah, counting sheep.’ It is clear from Stan’s reaction that for him this is not a joke.

And the joke becomes even less funny in retrospect as the film goes on. Stan spends every working day surrounded by sheep, his every moment defined by his identity as a ‘killer of sheep’; his work is all about sheep and all about killing them. The slaughterhouse scenes become more and more abstract, with sheep (alive and dead) repeatedly filling the frame, passing through it only to be replaced by identical sheep. At a certain point, in visual terms, it seems to make little difference whether they are live sheep running past the camera or sheep carcasses being transported (suspended on hooks) past the camera.

In one scene, the running sheep raise a cloud of dust that makes it even harder to differentiate them, so that they seem to be gushing past us in one continuous stream – no longer solid sheep but a fluctuating cloud of air particles.

In another scene, the long lens collapses the difference between Stan and the sheep he is herding, while on the soundtrack Dinah Washington sings, ‘If my life is like the dust that hides the glow of a rose, what good am I?’

Schoonover compared the uncanny alteration of materiality (in Sette canne) to ‘cinema’s central illusion of moving bodies,’ and the telephoto-lens shot is a powerful instance of this. What these proliferating sheep do to Stan, on an existential level, is suggested visually by the way he dissolves into them. He is a lot like those workers in the rayon factory, eclipsed by steam as they fed reeds into the boiling vats.

There is some optimism in Burnett’s film: Stan can occasionally be seen smiling while doing his job, and he chooses to remain a ‘killer of sheep’ rather than compromising his principles in pursuit of more lucrative or comfortable work. Nonetheless, I find the emotional tone of these ‘sheep-cloud’ scenes similar to the steam-cloud sequence in Red Desert, especially when considering the latter from Corrado’s perspective. Killer of Sheep is about people who never have enough money, but it is also – insofar as it focuses on Stan – about a person with a steady job, whose existence is therefore more secure than Antonio’s in Bicycle Thieves or Umberto’s in Umberto D. Charles Burnett, who listed Bicycle Thieves and Blow-Up in his Sight & Sound top 10, is less interested in the material effects of poverty than in the emotional and psychological impact of Stan’s environment. In the crushing moment when the motor drops off the back of the pick-up truck, the look on Stan’s face communicates more than a sense of lost money and lost opportunities. Like the photographer in Blow-Up, he is seeing through the broken object to the more profound brokenness behind it.

Likewise, it is not just the violence inherent to Stan’s job that traumatises him, but his sense of being defined as a ‘killer of sheep’ and the way he sees this identity mirrored back at him by the sheep themselves. They are nothing more than ‘sheep to be killed’, an amorphous mass that surrounds him physically during the day and fogs his mind at night.

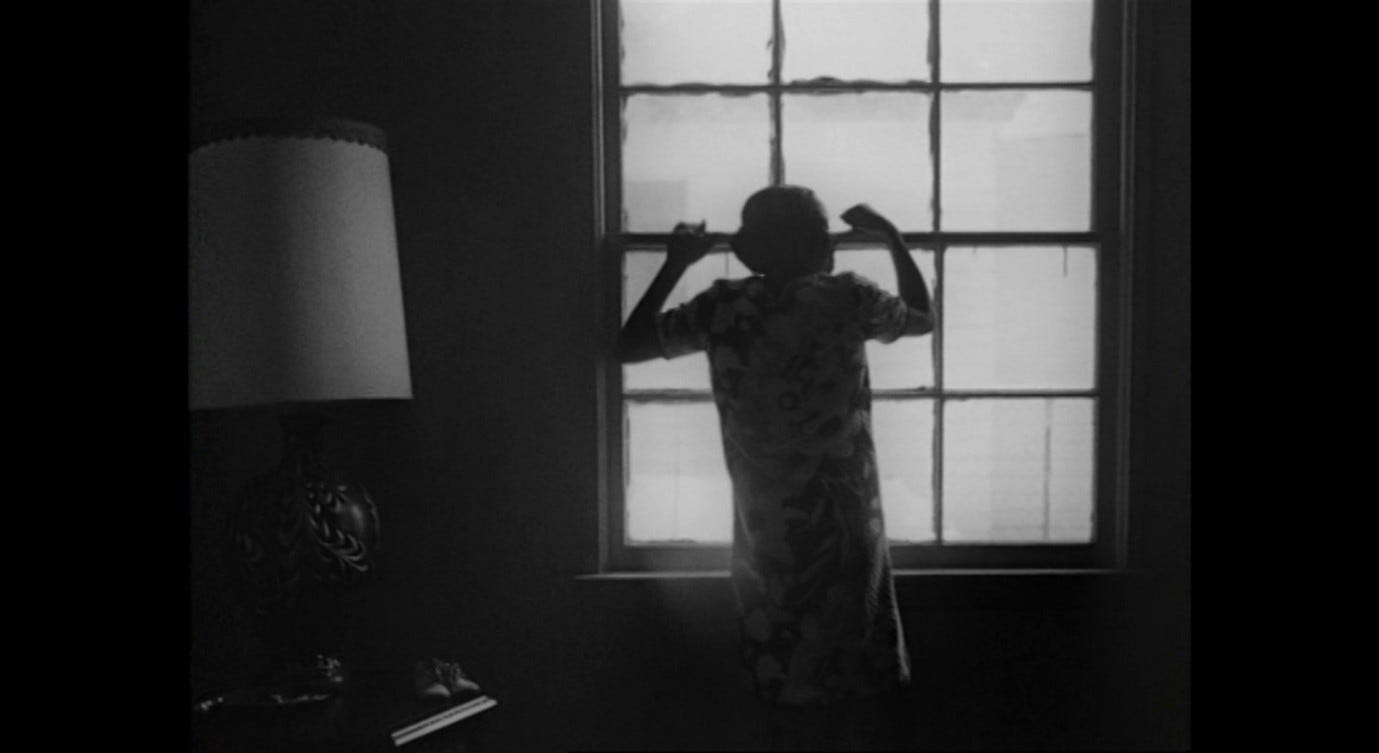

On one level, Killer of Sheep is about an unspoken inter-generational dialogue between the adults who work (or commit crimes) to sustain themselves and the children who sustain themselves exclusively through play. We see (from below) children jumping across the gap between two buildings, then the camera tilts down to find Stan walking through the constricted alley formed by those same two buildings. He looks up ruefully at the children whose movements are so much freer than his own.

In another scene, he comes home to find the children testing how long they can do handstands; in a comic echo of the ‘counting sheep’ line, one of them counts up to 500 but keeps losing count somewhere in the 450s. Stan interrupts the children’s game as he walks past, perhaps resentful that they have the luxury of counting nothing and for no reason, while he is haunted by the quota of sheep he kills every day.

As in Pather Panchali, another of Burnett’s favourite films, we see these children watching trains pass by as though foreseeing their own escape from this environment – in Killer of Sheep they also throw rocks at the train, hinting at a spirit of rebellion that perhaps bodes well for their future.

Burnett’s own entry into film-making was motivated by a desire to effect meaningful change:

It got to the point where it was just me and the kids making the movie, which was appropriate as the idea of doing the film was to demystify filmmaking in the community – to teach kids how to make films. I was into a group that was doing political films, that saw film as a tool to educate people, to do other things than to entertain.14

Killer of Sheep – his debut feature – in some ways stands for the transformative power of creativity. To be a maker of films (like this one) means representing experiences like Stan’s with honesty and clarity, but also showing the creative playfulness of the upcoming generation as a hopeful counterpoint. It is not that we imagine all these children becoming film-makers rather than killers of sheep, but that they might live in a world where the surrounding environment does not make them feel as alienated as Stan does. When Burnett surrounds the camera with sheep and sheep carcasses, he is reflecting on the father-figure’s working life but also asking how the children might perceive this life, and how they might find other paths to explore.

Inter-generational dialogues in Antonioni films tend to be more like Corrado’s wordless conversation with his dead father, which we see playing out in his melancholy facial expressions throughout Red Desert (although it is never referred to again).

We saw this, too, in Anna’s dialogue with her father at the start of L’avventura: their abortive argument over her relationship with Sandro was clearly, for Anna, related to some deeper sense of despair.

She decides to vanish from the film not only because of her identity as ‘fiancée of Sandro’, but also because of her identity as the daughter of her father, as a friend to Claudia, as a member of her social circle, and so on. These vaporous relations – ‘I don’t feel you anymore,’ she tells Sandro just before she disappears – surround her like fog, and once we understand this claustrophobic feeling we can easily understand why she looks so miserable and why she throws in the towel on her whole way of life.

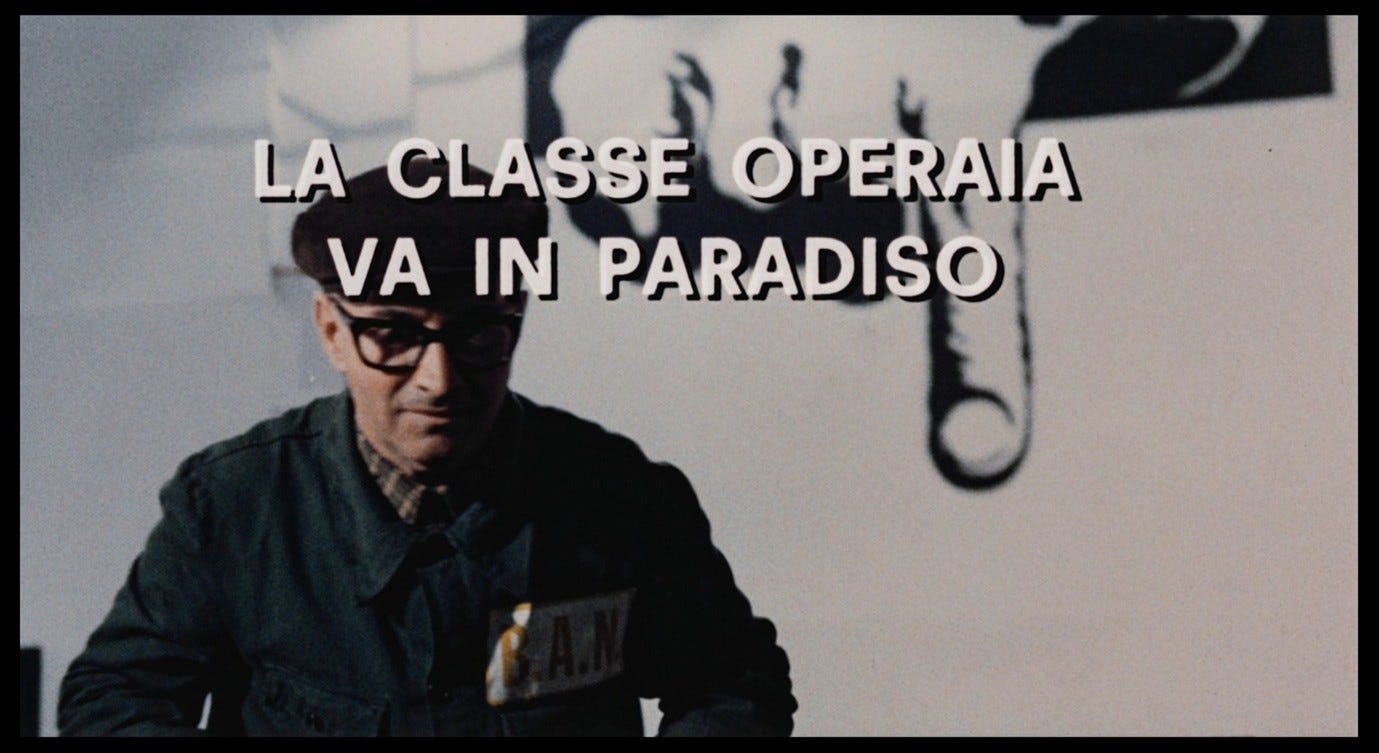

In The Working Class Goes to Heaven, the protagonist, Lulù, is haunted by his relationship with an elder colleague and mentor, Militina. Militina, like Lulù, was an exemplary worker, but was driven insane by the relentless labour that consumed his entire mind and being. Like Corrado unwillingly following in his father’s footsteps, Lulù worries that he is heading for the same fate as Militina.

In the dream that gives the film its title, Lulù imagines breaking down the outer wall of paradise, only to find a cloud of fog (‘nebbia’) behind it, from which he sees first Militina and then himself emerging. Then he says that the fog was also a cloud of brick dust and that all of his fellow workers were inside it. His attempt to recount and explain the dream is thwarted by the clamorous noise of the production line.

The film’s final shot freezes on an image of repetitive labour rendered abstract by the telephoto lens, over which the credits scroll upwards (beginning with the title).

As the downward-pointing finger painted on the white background suggests, that title is ironic: the working class ‘goes to heaven’, but heaven is only the confused fog that Lulù and Militina have been plunged into by their working conditions. Ultimately, this so-called heaven is a kind of hell, a freeze-frame like that at the end of Blue Collar, a portrait of inescapable (and inescapably violent) exploitation.

The dream-like vision of all-consuming steam in Red Desert contributes to our understanding of all three main characters in the film. It completes the picture of Ugo’s industrial mastery that has been accumulating throughout the ‘factory tour’ sequence. It adds texture to Corrado’s professional discontent, serving as a visual and aural manifestation of the forces that are keeping him in his current position; in that cloud he sees his Patagonian construction project, a great nebulous monster he does not understand but which he is somehow supposed to manage. And finally, as I suggested earlier, it is the nightmare from which Giuliana will wake up in the next scene, and which will recur for her in various ways throughout the film.

Next: we’ll be rewinding a few minutes for Part 9, The ‘love’ triangle.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 441

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Apropos of Eroticism’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 148-167; p. 160

Image credit: Anthony Rathbun, from Nudo, Meredith, ‘The Rothko Chapel’s Restoration Has a Long Road Ahead’ (15 January 2025), Houstonia

Lannes, Sophie, Philippe Meyer, ‘Identification of a filmmaker’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 245-256; p. 253

Lannes, Sophie, Philippe Meyer, ‘Identification of a filmmaker’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 245-256; pp. 253-254

Orr, John, Contemporary Cinema (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), p. 43

Orr, John, Contemporary Cinema (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), pp. 43-44

Schoonover, Karl, ‘Antonioni’s Waste Management’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 235-53; p. 249

Paulicelli, Eugenia, Italian Style: Fashion and Film from Early Cinema to the Digital Age (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), p. 228

Schoonover, Karl, ‘Antonioni’s Waste Management’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 235-53; p. 249

Schoonover, Karl, ‘Antonioni’s Waste Management’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 235-53; p. 249

Orr, John, Contemporary Cinema (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), p. 44

Paulicelli, Eugenia, Italian Style: Fashion and Film from Early Cinema to the Digital Age (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), p. 230

White, Armond, Alex Cox, ‘Slaughterhouse blues: Charles Burnett on Killer of Sheep’, Sight and Sound 12.7 (Jul 2002), pp. 28-30