Everything That Happens in Red Desert (6)

The scab, the sandwich, and the slag-heap

This post contains spoilers for Umberto D and Europa ’51.

Red Desert’s protagonist, Giuliana, is introduced to us through her encounters with a strike-breaker, with a striking worker who sells her a sandwich, and with the slag-heap where she eats this sandwich. Between them, these three encounters tell us something important about how Giuliana connects, or fails to connect, with the people and things around her. We sense a vague parallel between her and the strike-breaker, which is then compounded by her seeming alienation from his disapproving colleagues. Finally, in a confrontation that will resonate through the rest of the film, Giuliana faces the desolation of the industrial waste land, in which she finds a mirror and premonition of her own fate.

When she first appears, Giuliana is associated visually with the strike-breaker, Romeo Salviati. After the panning shot across the factory complex, we cut to a human’s-eye-level and see Romeo walking towards us, and towards the left-hand side of the frame.

We then cut to a reverse-shot of Giuliana walking towards us, and towards the right-hand side of the frame, mirroring Romeo.

This turns into a tracking shot as Romeo and his escorts enter the frame from the right and approach the factory entrance, crossing Giuliana’s path. For a brief moment, it looks as though she may have come there to meet him: she reaches for her son’s hand as if prompting him to join her so they can both greet Romeo.

Both she and Romeo are slightly less robotic than the crowd of strikers: he looks nervously over his shoulder before entering the factory complex, then again as he makes his lonely way across the factory yard; she looks nervously at him, and at the crowd that has been watching him.

Insofar as we have any emotions to latch onto in this first part of the film’s first scene, they are provided by Giuliana and Romeo. His visual isolation from the crowd is echoed by hers, except that the crowd’s attention is all focused on Romeo whereas Giuliana seems to be invisible to them.

After Romeo passes through the gate, we see carefully demarcated areas of bright green grass inside the industrial park, while the ground outside the factory walls has been reduced to an endless road of black mud with feeble strands of grass clinging to its edges.

Rolando Caputo, in his commentary on Red Desert, notes that the stand-out colours of the factory complex – the green grass and the beige buildings in the background – rhyme with the colours of Giuliana’s and Valerio’s clothes.1 This is perhaps more evident on the Madman edition, in which the beige of the factory is a little lighter, and closer to that of Valerio’s coat.

Through these subtle visual associations, we are unconsciously made to feel that Giuliana is like the strike-breaker in some way. The man with the megaphone urges Romeo to join the strike, telling him that he is not a ‘dirigente’ (a high-ranking executive) but someone who works to feed his children. The implication that Romeo has aligned himself with the factory managers also links him, subliminally, to Giuliana, the wife of a factory manager who is out for a lunchtime walk with her son (and will soon try, unsuccessfully, to give him food).

However, it quickly becomes apparent that she is not here to meet Romeo Salviati: if anything, she seems to have grabbed Valerio’s hand in a protective manner, perhaps unsure of whether Romeo’s escorts are protecting him or protecting others from him. So what is she here for? The film cuts from Romeo’s arrival at the factory to this out-of-focus shot of workers filing from left to right.

We are looking through the same eyes as in the title sequence, and when Giuliana – in focus – enters the frame, we understand that this is how she sees the crowd of workers, as a nebulous mass.

Giuliana moves against the flow of the crowd, from right to left, and when we cut to a reverse angle we again see her in focus and the workers out of focus.

Then one of the workers comes into focus for her, on the other side of the stream: he is standing with another man and eating a sandwich.

As with Romeo Salviati, we might think that Giuliana knows this man and is trying to get his attention. She seems nervous. Perhaps this is her husband, or a former lover, and she is unsure how he will react to seeing her.

The moment when we find out that this man is a stranger, and that Giuliana wants to buy his half-eaten sandwich rather than purchasing her own, is the moment when we realise that she has a problem.

The worker finds her behaviour inexplicable, but we may already have begun to understand and empathise with her. Her ravenous hunger in this scene is not just for food, but for a human connection.

The image of Giuliana walking against the flow of the crowd recalls a pivotal scene in Cléo from 5 to 7, in which Cléo’s path intersects with that of a long stream of pedestrians.

As these people cross the road, they seem almost like a funeral procession, striking a chord with Cléo who is preoccupied with her own mortality. In this sequence, around the mid-point of the film, Cléo has experienced a kind of rupture with her former self: the director Agnès Varda describes this rupture as a shift from seeing (and defining) oneself through other people’s eyes to seeing other people and defining oneself in relation to them.2 As Cléo wanders the streets of Paris, we see strangers glancing at her but then also looking at the camera. Then the camera fully inhabits her point of view, and we are conscious that these people are not looking at Cléo (or at Corinne Marchand) at all, but at Varda’s camera.

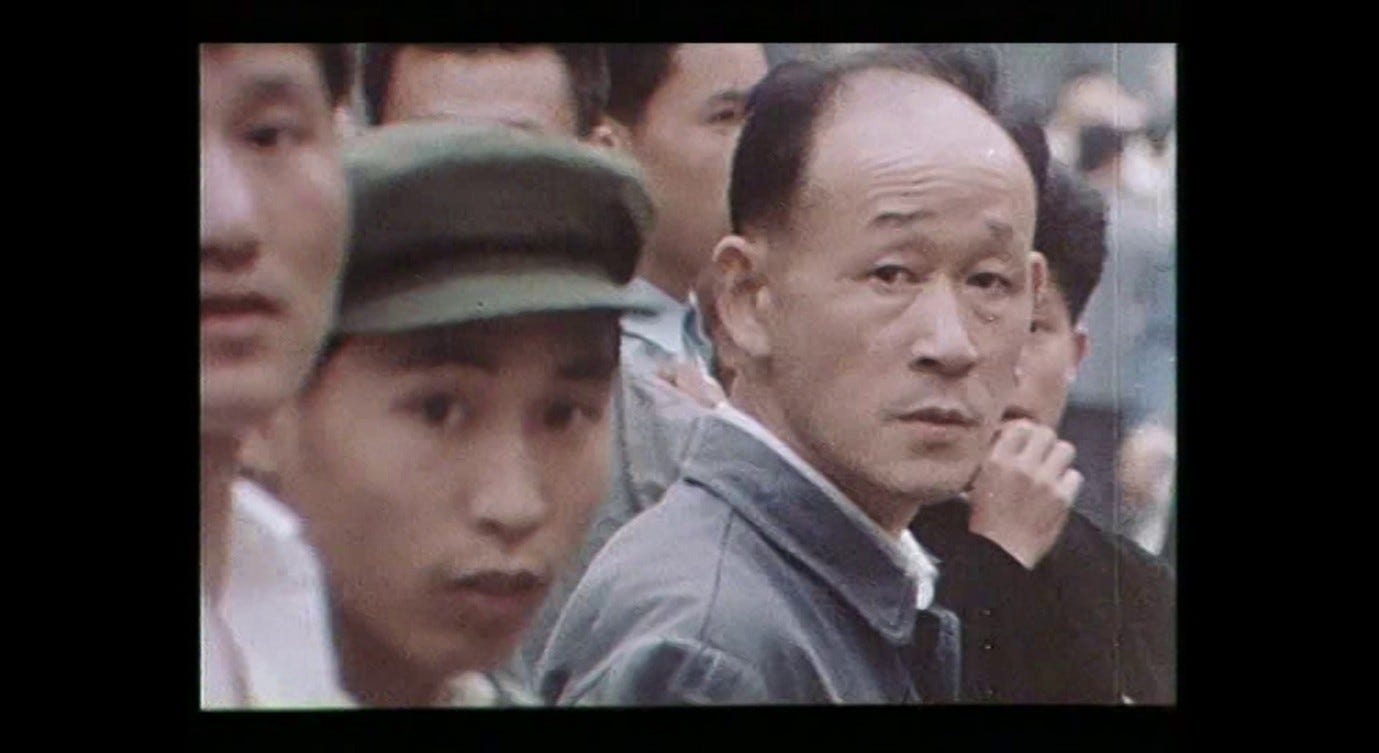

Some of them smile and laugh when they realise they are being filmed, but most look uncomfortable and even suspicious, much like the anonymous objects of the camera’s gaze in Chung Kuo: Cina whose faces move in and out of the frame, inspecting Antonioni and his crew and wondering why they are being filmed.

Alongside the documentary-style images of passers-by, Cléo also pictures other people’s faces in her mind – faces of her friends, of strangers she has just passed, and of inanimate objects that cannot look back at her – and they look directly into the camera lens as we look directly back at them. Reverse-shots of Cléo emphasise that these are internalised images she sees as she looks at her surroundings.

‘I feel afraid of everything,’ she later tells Antoine. ‘Everything amazes me today; people’s faces next to mine.’ In French, the latter phrase is ‘les figures des gens et la mienne à côté,’ which better conveys the feeling of separateness we got from those shot/reverse-shot juxtapositions of people’s faces and Cléo’s face in the earlier sequence. Now, in contrast, the image of Antoine’s face in the same frame as Cléo’s creates a sense of growing connection and meaningful dialogue.

Cléo’s fear of dying has triggered a deeper fear about her relationships with other people. Like Giuliana, she both longs for these connections and fears the effect they may have on her. David Forgacs, in his analysis of Monica Vitti’s acting, says that ‘Her face is at once an impenetrable mask, a magnet for spectatorial desire and a channel for empathetic identification.’3 He could just as easily be talking about Cléo (or Corinne Marchand), and his comment hints at the uncomfortable mix of emotions with which both Giuliana and Cléo face their fellow human beings.

Lidia, in La notte, escapes from the suffocating artifice of her husband’s book-signing to look for signs of life outside. Although she communes briefly with a succession of fellow human beings (a man eating a sandwich, two friendly drunkards, a crying child, an unfriendly office-worker, a woman eating something out of a pot, and a gang of aggressive young men), her journey ends in disappointment and loneliness. At the start of this odyssey, she is juxtaposed with a pillar bearing the number ‘2’; as her loneliness sets in, she is juxtaposed with another bearing the number ‘1’.

As Seymour Chatman says:

We feel [Lidia] coming to understand that her disturbed relationship with her husband is not unrelated to the arid, empty, abstract space in which they live. She sees the same problem in the faces of [passers-by].4

Giuliana’s efforts are even more futile, provoking consternation in the sandwich-eating worker and causing embarrassment for herself and her son. She has her reasons for not wanting to buy food from some anonymous café, and for wanting one that has been partially eaten (and is therefore ‘shared’), but practically, there is no way to explain these reasons or mitigate the strangeness of her behaviour. In Les rendez-vous d’Anna, we see Anna crouching down to eat leftover food in a hotel corridor. After a few bites, she becomes self-conscious, throws the last handful of food back onto the plate, and returns to her own room. Later, we see that she has ordered room service for herself and fallen asleep under it before finishing.

This is one way among many in which Chantal Akerman communicates Anna’s feeling of alienation from other people: like Lidia and Giuliana, Anna makes furtive attempts at connection from which she then furtively retreats, unable to express her emotional hunger except through spasmodic gestures and thousand-yard stares.

Having committed herself to paying for the sandwich, Giuliana grabs money from her pocket and then rifles awkwardly through the banknotes.

The screenplay specifies that she pays 2000 lire (just under €30 in today’s money)5 for the sandwich, and while we do not see the specific amount in the film, it is clear from the worker’s reaction that she has overpaid him.

Giuliana, as the wife of a factory boss, cannot simply take food out of an employee’s mouth, especially when he is on strike; she has to pay him for it. By paying too much, she draws attention to her own wealth and status, exposing the social gulf that makes this connection impossible. Throughout her conversation with him, Giuliana cannot stop looking at the worker or stop looking away from him: she is unable to connect but unable to give up trying.

Angela Dalle Vacche notes a parallel and contrast between the protest sequences at the start of Umberto D and Red Desert: if the former, in 1952, alluded to the way the ‘civic ideals of the Resistance movement [had] been betrayed,’ then Red Desert focuses instead on the ‘social turmoil that characterized the early sixties in the wake of the so-called economic boom of the previous decade.’6 Umberto Domenico Ferrari’s connections to other people (and even, intermittently, to his dog) disintegrate under the pressure of the money-driven context of early-50s Rome; in the world of Red Desert, ‘new financial ventures and cutting-edge technologies have upset traditional relations, not only between workers and management but also between human beings and their environment.’7

We first meet Umberto as one among many protestors, then follow his individual journey into an ever-greater state of destitution as he becomes effectively invisible to society.

That journey revolves around the very specific amounts of money he needs to pay his rent, for which he tries to barter his belongings, or with which he considers paying for his dog’s board and lodging.

In Red Desert, we meet Giuliana as an emblematic outsider-to-the-crowd who wants to connect with the mass of protestors, but whose very non-specific offer of (unwanted) cash illustrates why she remains alienated from them. Our focus has shifted from the poverty-stricken protestor to the prosperous manager’s wife, and while the breakdown in social relations still has an economic component (i.e. it is still somewhat rooted in the divide between rich and poor) it clearly functions on an existential level as well.

As Giuliana backs away from the worker in mortification, she offers the sandwich to her son, as though she had only been trying to feed him. He flatly refuses to play along, so Giuliana gives up and retreats into a solitary space.

Imagine an alternate version of this sequence: we arrive on the scene with Giuliana, she encounters a furious crowd of striking workers, she sees them yelling at the strike-breaker, and through this experience she comes to understand and sympathise with their point of view. They are oppressed by the same de-humanising industrial forces that make her feel alienated and out of place, and she begins to think about joining (or somehow supporting) their struggle. In this version of the story, Giuliana would be like Irene Girard in Europa ’51. We first meet Irene complaining about the inconvenience caused by a transport strike, but as the film progresses she abandons her bourgeois lifestyle in order to fight social injustice. As a result, she is labelled insane by her family and friends, but is ultimately revered by the working-class community that forms around her.

The troubled mother/son relationship in Red Desert, and the fact that Giuliana is seen as mentally ill by her husband, may well remind us of Rossellini’s film, but the comparison throws into relief how different the two stories are. For Rossellini, social problems must be faced head-on and at first-hand so that these bonds can be repaired. Even in the bleakest moments in Europa ’51, we feel that the values of love and kindness can make the world a better place. As Angelo Restivo says:

the Rossellini/Bergman films always culminate in the epiphanic moment that – however ambiguous – serves ultimately as an anchoring point; it is precisely this moment that is rigorously excluded from Antonioni’s work.8

Indeed, while the denouement of Irene’s story is open-ended and emotionally complex, it feels cathartic because there is a (clearly genuine) connection between her and the people crying below her window.

The validation of this social bond feels like a transformative epiphany that should move the audience towards some kind of positive action after the film is over. Sam Rohdie delineates the contrast between these two directors in terms of optimism vs. pessimism, but also as a difference in attitude towards the kinds of rupture that both Rossellini and Antonioni are preoccupied with:

[Rossellini] viewed the uncertainties, the malaise of the present not as an opportunity, so much as a misfortune in need of correction…and correctable. […] Antonioni is too uncertain to be a teacher, and too excited with the possibilities offered by misperceptions, by fragility, by the dissolution of things.9

The problems Antonioni is exploring are, as he portrays them, inevitable and incurable. Fighting for social justice is now just another routine the workers go through. There is no cause for Giuliana to take up and no bond that she can form with these workers, even through the most basic communal activity like ‘breaking bread’. And, as Rohdie points out, this failure to connect opens up a very different set of creative possibilities from those that were explored within Rossellini’s more optimistic framework.

Giuliana also struggles to bond with her son. At the start of Europa ’51, Irene tragically fails to notice how much her son needs her, and he falls to his death in an apparent attempt to get her attention. This traumatic breakdown in a familial relationship prompts Irene to seek out other needy people in the world beyond her home. The tragedy of Giuliana’s relationship with Valerio is that, as she will say later, he does not need her at all. While his mother purchases the sandwich, Valerio is quite content to amuse himself, robotically stepping from left to right and back again along a metal rail.

‘No,’ he says, and then again, ‘no,’ coldly and firmly, when his mother offers him the sandwich. His hair is lighter than Giuliana’s, closer to the colour of his skin and his coat, so that apart from his black boots and shorts he seems to be all one colour, very ‘uniform’. His self-sufficiency, decisiveness, and emotional restraint make him seem like a walking critique of his mother, who has none of these qualities.

Early in Paper Moon, when Moze is buying a train ticket to get rid of Addie, we see her behind him staring impassively down the railway track; later, when her superior intelligence and aptitude have become painfully obvious to Moze and he is trying to get a refund for the ticket, we see Addie tightrope-walking back and forth along a rail. This set-up may have been inspired by the similarly painful (but less comedic) visual contrast between Giuliana and her well-coordinated son.

In a lingering shot of Valerio after Giuliana has left the frame, his lips are turned down for a moment, as if to express sadness, but then his face becomes blank again.

He is not like Irene Girard’s son, upset at being rejected by his mother and resorting to extreme gestures to win back her affection, nor is his stony face a prelude to eloquent fury, like Addie Pray’s. His momentary expression of sadness is just a face he is pulling to have something to do, much like his idle side-stepping along the rail. It is Valerio who rejects Giuliana: she has not left him behind, rather he is hesitant to follow her because he finds her embarrassing. At the end of this sequence, when he runs after her and takes her hand, there is a sense that he is ‘fetching’ her to take her home, after letting her play out her strange, solitary ritual with the sandwich. As they leave, Giuliana will stroke his hair affectionately, but there is no indication that he reciprocates this affection.

From the beginning of Red Desert, Valerio is an unsettling and robotic companion for his mother – ‘a little zombie,’ as Robin Wood calls him, drawing comparisons with the pod people in Invasion of the Body Snatchers.10

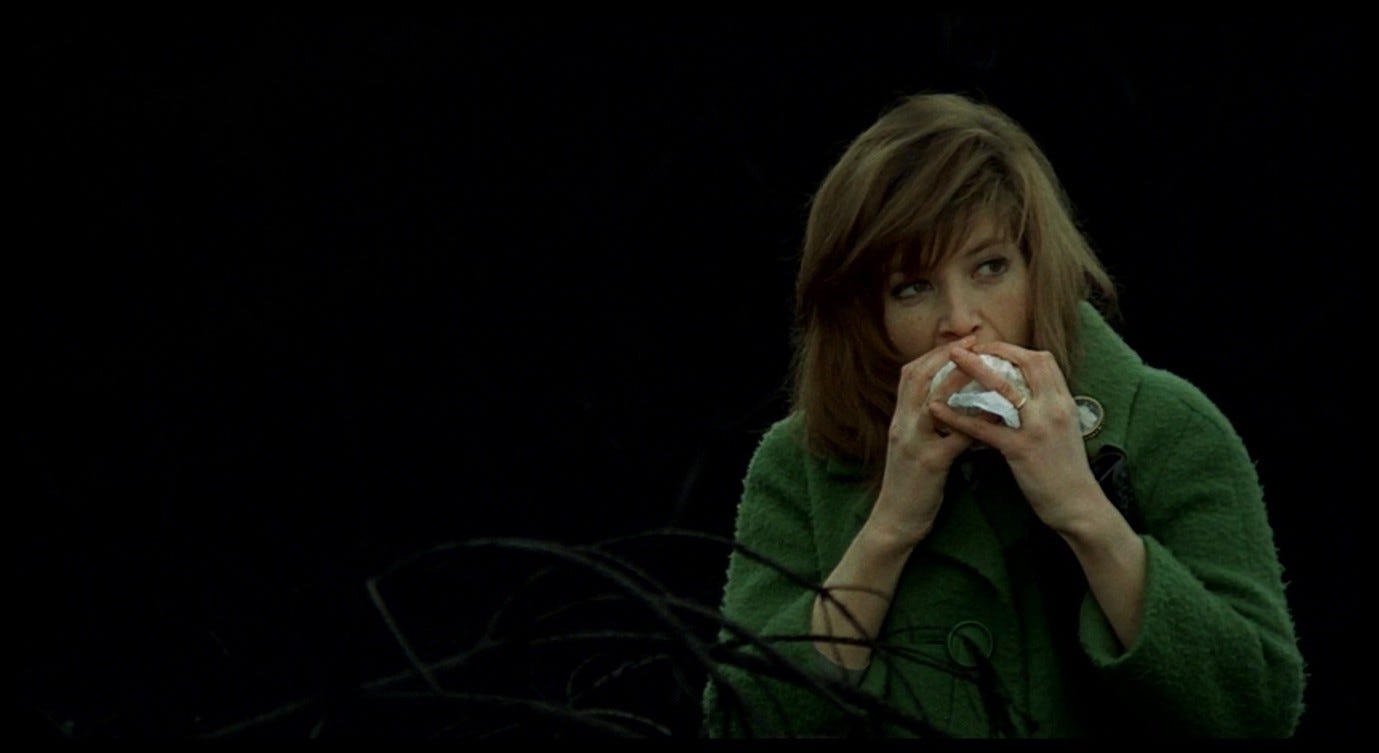

Giuliana escapes from her embarrassing encounter with the worker into a secluded spot behind some trees. The clearing is shockingly polluted. The few tufts of green grass seem as out of place here as Giuliana does, and the prevailing visual impression is of blackened vegetation beneath a grey sky. Before she can start eating, Giuliana has to take refuge behind some protruding branches, then she looks around as though checking for predators. When she finally bites into the sandwich, we cut to a medium shot so that we can register the extent of her relief. After swallowing the first mouthful, she takes a deep breath and exhales quickly, before stuffing the sandwich into her mouth again.

The screenplay specifies that Giuliana cannot eat in front of the workers because she is ‘suddenly overcome with shame,’ that she tries to offer the sandwich to Valerio ‘in an attempt to make him her accomplice,’ and that she runs away because she is ‘confused and unable to contain her urge.’11 In addition to the social awkwardness I commented on above, it is the intensity of Giuliana’s impulse that makes her ashamed and drives her into solitude. When we see her breathless, unrestrained attack on this sandwich, we understand that there is something socially unacceptable about her hunger. The sandwich’s original owner stood eating it with one hand in his pocket while carrying on a conversation, not clutching it in both hands, gasping for breath in between mouthfuls, looking furtively around him.

Giuliana cannot find anyone to share food with her because no one is as hungry as she is, and (by the same token) because it is not appropriate to be as hungry as she is. (This is perhaps why the hyper-restrained Anna in Akerman’s film abandons her hotel-corridor meal, ashamed of her open display of corporeal desire even when no one else can see it.) As Red Desert goes on, we will gain a deeper insight into what Giuliana’s ‘hunger’ stands for and why it is seen as inappropriate.

The film cuts from a wide shot of Giuliana, behind the branches and at the centre of the frame, to a medium shot of her in which she is pushed to the right-hand side of the frame.

It then cuts back to the wide shot for a few seconds, only to cut to another medium shot, this time from a different angle and with Giuliana centred in the frame. The approach to editing and composition here is playing off Giuliana’s ‘marginal’ status, on the sidelines of the modern world, against the idea of her centrality: she is the centre of the film, but also at the epicentre of the red desert; in an important sense, she is the red desert.

We have cut to a noticeably lower angle, framing Giuliana against the blackened trees behind her. The jet of yellow flame from the first establishing shot pipes away insistently in the far background. That ‘ah-ah-ah’ noise that interrupted the title sequence (and Giuliana’s song) has not stopped throughout this scene, and now we are reminded of its origin. The flames appear to be piping out of the trees themselves, as though the flare stack were a kind of tree, or as though the trees had been incorporated into the factory complex. The trees appear to have been burnt, in fact, and seeing these victims of industrial processes (with Giuliana herself, in her grass-green coat, standing vulnerably among them) may prompt us to reflect that the incessant flames have to come from somewhere – they have to be burning something.

The cut to this low angle occurs at the moment when Giuliana turns around, stops chewing, and stares in horror at an off-screen space now occupied by the camera.

Indeed, this is like a moment in a horror film when a character reacts to something out of frame before the audience has had a chance to see it. The bleak forest-fragment behind Giuliana gives us a clue as to what she has seen before it is shown to us directly. She is looking at the slag-heap where waste products are dumped and burnt, a seething desert of black-and-yellow garbage. Unidentifiable hunks of scrap, stained with rust or poisonous effluent, merge with the prevailing grey muck. A hillock of steaming soot disintegrates before our eyes.

This sequence introduces an idea that will pervade the rest of the film, namely what Karl Schoonover calls ‘the powerfully insistent presence of refuse.’12 He contextualises this idea in terms of the prosperity of early-1960s Italy, in a way that resonates with my earlier discussion of the contrast between Umberto D and Red Desert:

A hyperbolic upsizing of large-scale industry’s infrastructure in Europe ushered in the economic miracle […] [T]he new era of plenitude promised to whisk away postwar squalor with an array of dazzling commodities. Yet plenitude also came with a new kind of trash. […] Detritus no longer decomposed; it threatened to fill our lives, crowd us out and outlast us. […] The permanence of new forms of garbage took us by surprise: these new materials not only refurbished our standard of living, but also overspilled, contaminated and leached into our environment and bodies. Living with toxic waste seemed to haunt commodity culture’s promise to eradicate need.13

Ostensibly, the slag-heap Giuliana stares at is supposed to be a place where detritus decomposes. But instead of decomposing, it metamorphoses and multiplies into a sort of black quicksand that creeps over the garbage dump and gradually infects the entire area, even climbing up into the trees. Schoonover’s link between plenitude – the ‘promise to eradicate need’ – and this over-plenitude of waste products is especially poignant because this sequence focuses on Giuliana’s need, her literal and emotional hunger. Food is plentifully available in the nearby shop, yet Giuliana recoils from this as a kind of unwanted excess; she would rather finish a sandwich someone else has started. Umberto D purchased and then discarded (and smashed) a piece of glassware, simply in order to get the change he needed for his taxi fare and to save his dog from the pound.

Like Giuliana, he found himself in a world where the banknotes are too large and the commodities too plentiful, but the consequences for him (of not having money and things) were destitution and starvation. Clearly, Red Desert is not about running out of money and perishing; it is as if Umberto became prosperous and physically healthy, but were still being eroded from within by the same culture of excess, grown now to monstrous proportions.

What I find most interesting about Giuliana’s confrontation with the slag-heap is not the sense that the waste products have made it impossible for her to survive here, placing her in a kind of mortal peril equivalent to Umberto’s (though that is part of what this scene conveys). There is also a sense that she identifies with these waste products, and that their surprising persistence mirrors her own. Later in Red Desert, looking at the polluted waters of what used to be a prime fishing spot, Ugo will remark philosophically that ‘effluent has to end up somewhere.’ There, too, Giuliana will be fascinated by the blackened and yellowed ponds and trees, prompting Corrado to ask, ‘What are you looking at?’ She is fascinated by and drawn to such scenes because they show her the ultimate fate of ‘waste’, of the useless scum that is refined away and expelled from the hygienic, efficient world that Ugo and others like him have built for themselves. She is afraid that the same fate awaits her.

Giuliana will not quite perish in this hostile environment, but instead will just barely survive on its margins. Here again is Antonioni’s explanation of the title, Red Desert:

‘Desert’ perhaps because there are few oases left; ‘red’ because it’s blood. The living, bleeding desert, full of the flesh of men.14

At the end of Part 5, I described Giuliana as an oasis of brightness, colour and clarity, surrounded by greyness and obscurity. In her first scene, when she encounters the slag-heap, Giuliana surveys the desert created by industrial processes: an oasis burnt to ashes. Later in the film, she will re-discover the oasis by conjuring it in her imagination. But as Antonioni’s comment about blood and flesh reminds us, the problem is not just that the oasis has been destroyed; the desert that replaces it is alive and bleeding, just as the pink rocks in Giuliana’s oasis-fantasy will seem to be alive. In T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, the desert at first seems to contain only ‘stony rubbish’ out of which nothing can grow:

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water. Only

There is shadow under this red rock,

(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.15

In Red Desert, Giuliana seeks out the dead and blackened trees for shelter, and what she finds is something like ‘fear in a handful of dust.’ The most obvious meaning of Eliot’s phrase is ‘fear of mortality’: the desert reminds us that we came from and will return to dust, we realise we are nothing more than ‘a handful of dust,’ and we are afraid. Fear of mortality, and fear of change more broadly, is a key theme in Antonioni’s work. But in Red Desert, death is not (I think) what Giuliana is truly afraid of. In her waste land, it is as though the dust itself, and the red rock, and all these inanimate objects with whom she communes, are alive and afraid: they contain fear as well as provoking it. The prospect of being poisoned and killed by this place seems frightening enough; but like the Sibyl who provides the epigraph for The Waste Land (‘I want to die’), we might find the prospect of surviving here even more frightening.

The slag-heap looks like a black and yellow desert, but in a sense it is ‘red’ because it indirectly consumes lives, human and non-human. Giuliana is in the process of being consumed by it: she gives the impression of always being on fire, always burning with anxiety, always in danger of ‘burning out’, yet never finally expiring. She and the steaming, creeping landscape she wanders through are two manifestations of the red desert, the oasis turned into an ever-welling, ever-simmering pool of sentient flesh and blood. John Orr describes the slag-heap encounter in a way that suggests both Giuliana’s fear of and identification with the toxic waste products that surround her:

Through a strange anthropomorphic switch her figure seems to have taken on in garish hues the normal colours of trees and plants which are now black and withered […]. When she turns to see yellow spurts of poisonous flame come out of the refinery’s stacks, the yellow seems a further dilution of the green which is not there, a travesty of nature like the colour of the coat she wears.16

This almost makes Giuliana sound like a parasite who has leeched the colours of nature into herself, like that figure in the Tintal advert who has appropriated the green of the forest for the wall of her home (discussed in Part 2).17

In this reading, Giuliana does not simply mourn the loss of green vegetation, she becomes (unwillingly) a walking travesty of nature, just as her exchange with the worker was a kind of travesty of generosity and social connectedness. Her coat stands for the green that has been burnt away, her misjudged wad of cash for the cross-class connections (envisioned by Rossellini) that failed to materialise. Noa Steimatsky also reads Giuliana’s green coat as one step removed from the ‘original’ green of nature, but in a more positive, generative sense:

[W]hen Monica Vitti emerged into the polluted landscape in her green wool coat – a green exquisite in its break with both the natural vegetation and with the primary-color industrial palette – person and coat could speak or, by fantastic counterpoint to the setting, could sing together.18

This is the Antonioni Rohdie described earlier, ‘excited by possibilities,’ marvelling at the ‘boiling energy’ of Giuliana’s environment (as Chatman put it in Part 5). We might say that Giuliana experiences her coat, and even her self, as a parasitic ‘travesty’ of the natural world, while the camera sees something exquisite and hears a fantastic new song. That joy in exquisite new things is itself part of Giuliana’s anguish, though the viewer may choose not to experience it as such.

Sławomir Masłoń reads this episode in terms of Giuliana’s search for an identity and a role:

[B]y buying a worker’s sandwich and eating it agitatedly, she tries to incorporate into herself a beyond which is not just an individual fantasy (like the mysterious ship [in the story of the pink beach]) which may help her to find or re-find meaning in the family constellation as a wife and a mother, but which would include a wider social bond that could tell her who she is beyond the domestic roles.19

The chronology is interesting here: we see Giuliana tending to her ‘wider social bond’ before we have seen her in the domestic space, and long before we have seen her ‘individual fantasy’ of the mysterious ship. In a sense, it is the same narrative structure as in Europa ’51, in which we meet first an anonymous couple and then Irene commenting on the industrial action (the anonymous husband rebukes his wife for her lack of social consciousness; Irene’s husband, tellingly, does not). But by giving so much more time and emphasis, in the very first scene of the film, to Giuliana’s social alienation, and by connecting this to her alienation from her own son, Red Desert sets up its protagonist as someone who cannot ‘reach out’ for connections beyond her immediate sphere. Her journey, some of which she will (try to) take with Corrado’s help, can only take her further inwards.

Next: Part 7, Inside the factory.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Caputo, Rolando, Commentary track, Red Desert (DVD, Madman Entertainment 2006).

Remembrances (d. Agnès Varda, 2005), available in The Complete Films of Agnès Varda (Blu-Ray, The Criterion Collection 2020)

Forgacs, David, ‘Face, Body, Voice, Movement: Antonioni and Actors’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 167-182; p. 173

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 96

Historical Currency Converter, fxtop.com

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 44

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 44

Restivo, Angelo, The Cinema of Economic Miracles: Visuality and Modernization in the Italian Art Film (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022), p. 97

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 59

Cameron, Ian, and Robin Wood, Antonioni (revised edition) (New York: Praeger, 1971), p. 116. The quoted passage is from the latter part of the book, which was written by Wood.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 436. My translation.

Schoonover, Karl, ‘Antonioni’s Waste Management’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 235-53; p. 238

Schoonover, Karl, ‘Antonioni’s Waste Management’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 235-53; p. 239

Manceaux, Michèle, ‘Dans le Désert rouge’, L’express (16 January 1964), pp. 19-21; p. 20. My translation. For a fuller discussion, see Part 2 of this series.

Eliot, T.S., ‘The Waste Land’, in The Complete Poems and Plays of T.S. Eliot (London: Faber, 2011), pp. 60-80; p. 61, ll. 20-30

Orr, John, Contemporary Cinema (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), p. 43

Image posted by ebay.it seller ‘stems23’, item listed as ‘advertising Advertising 1967 TINTAL MAX MEYER’

Steimatsky, Noa, The Face on Film (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 186

Masłoń, Sławomir, Secret Violences: The Political Cinema of Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960-75 (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2023), p. 114