Everything That Happens in Red Desert (7)

Inside the factory

This post contains spoilers for Blue Collar and Human Resources.

In the first eight minutes of Red Desert, our relationship with Giuliana’s world has been established in complex and ambiguous terms. We are disturbed by this place, like her; we are also familiar with it and can navigate it easily, perhaps to the point of feeling complicit in its impact on her; and we have begun to understand how she can be both marginalised by and emblematic of this environment.

In the first part of the following sequence, in Giuliana’s absence, we will meet her husband and explore the factory from his point of view, deepening our empathy for the robots and the pod-people, so to speak. It is important that we understand the relatively untroubled world they inhabit before we begin, in earnest, our slow descent into Giuliana’s nightmares.

Like the first scene, the second begins with a dramatic transition, and again this works on both the visual and aural levels. The wide shot of the smoking grey-black desert, with Giuliana and Valerio walking through it, is interrupted by a cut to a set of bright red power transformers.

The ‘ah-ah-ah’ sound of the flare stack from the previous scene does not cut out immediately, but gradually recedes to make way for the transformers’ continuous electronic hum. Then the hum also becomes quieter – and the sound of the flames disappears almost entirely – as we cut from the slightly out-of-focus long-lens shot to a clearer wide shot that locates the transformers in relation to the factory.

This is the same scene-setting technique we saw a few minutes ago, in the cuts from the flames, to the flare stack, to the factory complex. The juxtaposition of different perspectives makes these structures both strange and familiar to us. Antonioni, while making this film, altered his technique in order to encompass multiple perspectives:

Until Red Desert, I always filmed with a single camera, and thus from a single angle. But from Red Desert on, I began using several cameras with different lenses, but always from the same angle. I did so because the story demanded shots of a reality that had become abstract, of a subject that had become color, and those shots had to be obtained with a long-focus lens.1

The red transformers are seen from the same angle by two different cameras: the first shows reality transformed into a blur of abstract colour; the second shows reality, plain and simple, in a comprehensive wide shot. At the start of the previous scene, we were wrenched out of Giuliana’s perspective and into a more clear-eyed mechanical one. The effect here is less violent, in accordance with what these sounds and images are telling us about the factory complex. The explosive noise of the flare stack, which served as a backing track to that whole first scene, was associated with destructive industrial processes, with the protesting workers, and with the burnt debris of the slag-heap. Now we move to a cleaner, more controlled setting, from the pulsing roar of the flames to the steady hum of the transformers, from surplus gas and refuse being combusted to energy being channelled and controlled.

When we then find ourselves inside a control room in the factory, the noise changes again, but it is still a continuous noise, not a pulsing one. We hear a loud, steady roar coming from somewhere. Then an alarm goes off, drawing everyone’s attention. One of the workers says ‘The temperature of the steam is high,’ addressing his boss as ‘ingegnere’ (‘engineer’). Ugo calmly enters the frame to solve this problem (‘Lower the burners a little’) and we hear no more about it. In short, this is a controlled environment, full of potential dangers that are scrupulously kept in check: high voltages moderated by transformers; high temperatures cooled by Ugo.

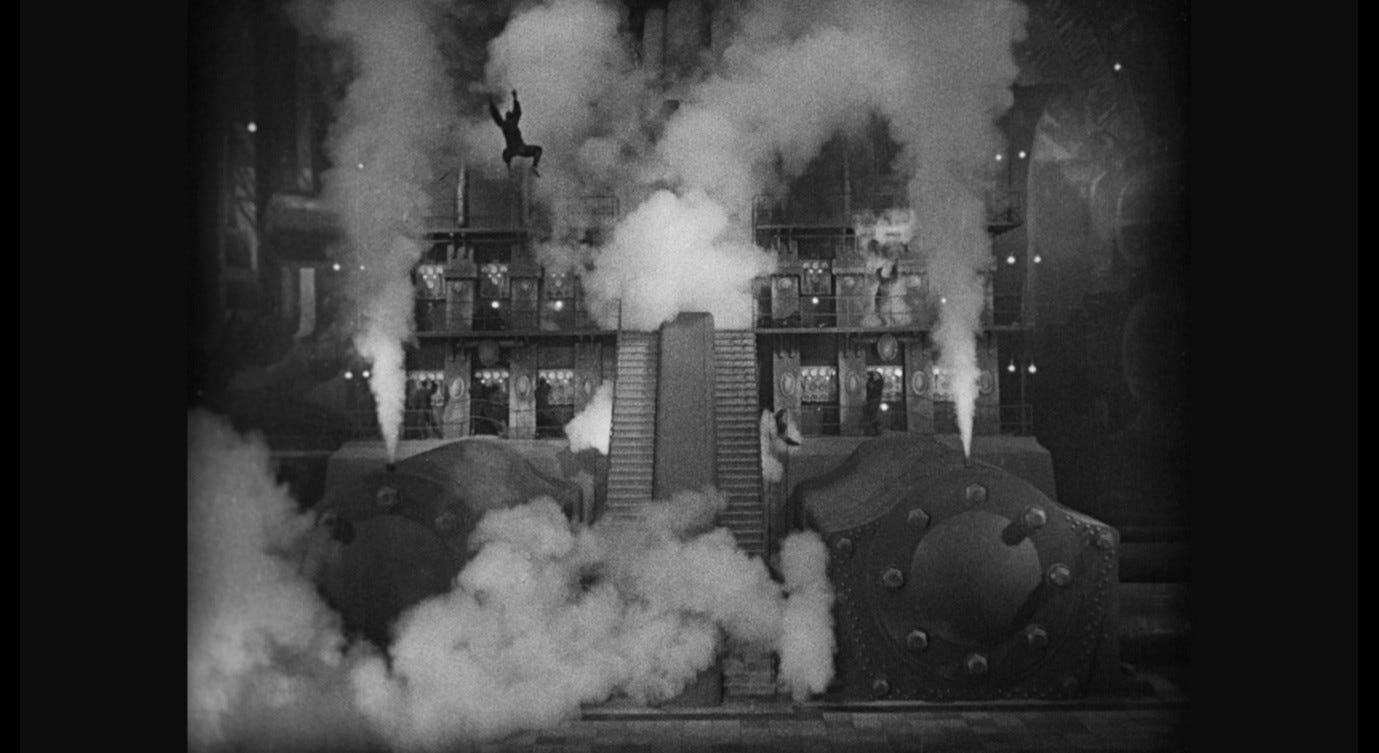

Sławomir Masłoń notes that these ‘dials and levers [are] straight out of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis,’ and sees this as part of Red Desert’s project, in its opening scenes, to evoke a futuristic dystopia (which we are then almost surprised to learn is just current-day Ravenna).2 Near the start of Lang’s film, we are introduced to the subterranean factory as a place where temperature regulation is all-important. Workers are forced to spend ten hours a day adjusting instruments to keep the M-machine’s energy in check: when one worker collapses and is unable to pull the required levers, the mercury in the thermometer rises above the maximum limit. The other workers try frantically to make adjustments, but they are eventually scalded (and in some cases propelled through the air) by an explosion of steam.

Freder, watching in horror, has a hallucinatory vision of the ancient god Moloch, consuming bound slaves and uniformed workers as they are thrown (or as they simply march of their own accord) into its mouth.

Metropolis presents a nightmare vision of the future in which productivity is pursued at any cost: the Moloch-machine is like the flare stack in the first scene of Red Desert; the gaping mouth and relentlessly churning gears are like the roaring ‘ah-ah-ah’ song; and Freder is like Giuliana seeing how objects and people are indiscriminately burnt by these industrial processes, in hidden-away spaces.

The big difference is that, in Red Desert, the workers too are largely (or nominally) protected from that ugly reality. Instead of being forced to work in a state of constant mortal peril, these Moloch-maintainers inhabit a pristine control room that is almost devoid of visible hazards. When there is an excess of heat, that heat and the burners that control it are at a safe distance, and a simple adjustment of a dial can solve the problem. In Metropolis, we were asked to believe that the dystopia could be turned into a utopia through the sentimental idea that ‘the mediator between the head and hands must be the heart’ – that is, through the intervention of Freder’s care and compassion in the relationship between managers and labourers. There is no hint of this in Red Desert when the executive reminds Ugo that ‘we are a state-owned company [azienda statale]: no layoffs.’ Workers’ rights are regulated by the state, companies comply with these regulations, and such compliance is as cold-blooded and by-the-numbers as the strike we saw at the start of the film.

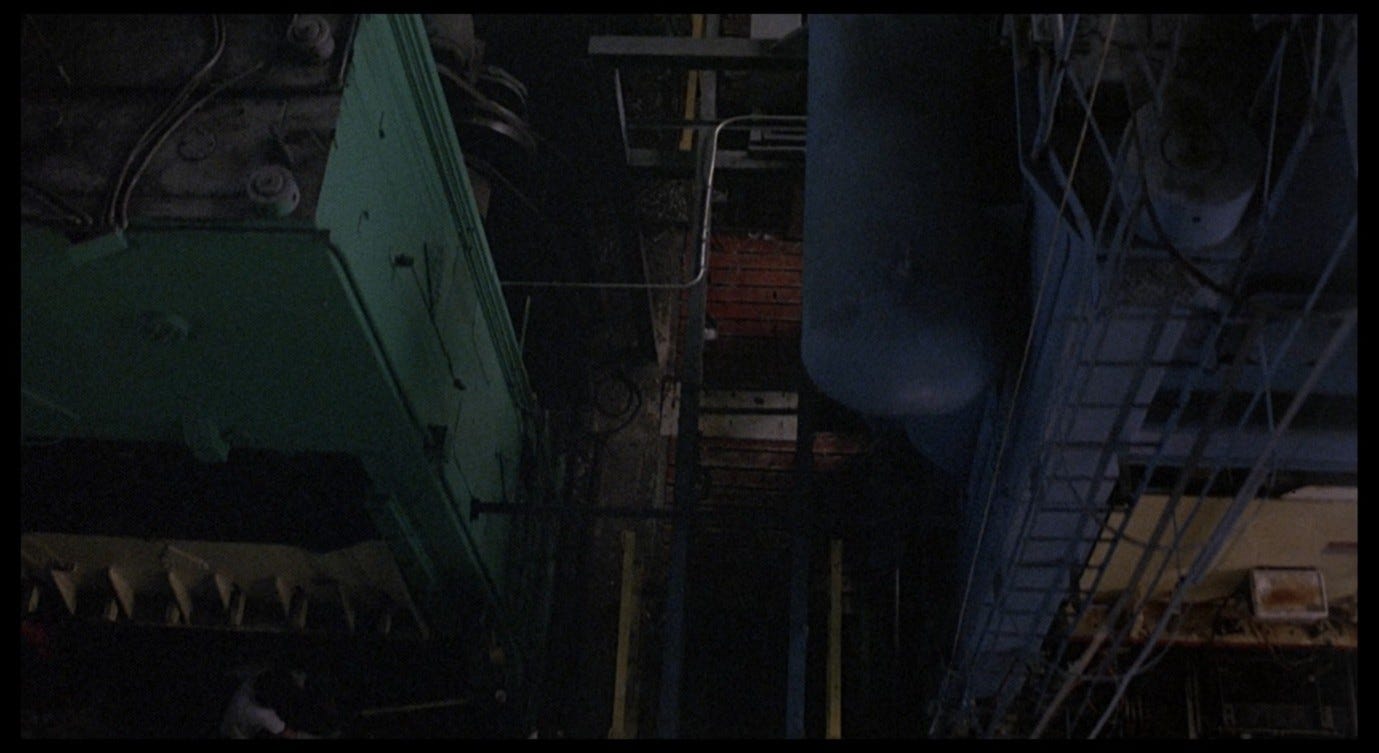

In that first scene, we saw a largely monochrome world ruled over from above by a distant jet of yellow flame, with premonitions of brighter colours in the outdoor complex through which Romeo Salviati walked. Inside the factory, things are more colourful, and the colours are all significant. The control room and Beltrami’s workshop are predominantly blue.

This is appropriate to the blue-collar work being done in these rooms: dirt and stains show up less on blue uniforms. Beltrami’s cavernous work-space is a noticeably darker shade of blue (closer to grey depending on which edition of the film you watch), the workers here wear hard-hats, and some of the machinery in the background is painted red or green. This hints at class distinctions between the different work-forces: one is more likely than the other to get their overalls dirty, to have something fall on them, or to be maimed or electrocuted.

Ugo, the boss in the control room, is more smartly dressed than the workers he commands, though not quite in a suit, and still primarily wearing dark colours.

He is dressed in a light brown jacket, dark blue cardigan, dark purple tie, and grey trousers. His blue-chequered white shirt (most of whose surface area is white), though protected by the cardigan and jacket, signifies that he is less at risk of sullying his clothes than the men at the control panels. He wields authority but as an ‘ingegnere’ he still does hands-on work in a range of different spaces. Occupying an intermediate position, at a table in the control room, is a man wearing a green jumper, with a shirt collar sticking out at the neck. If only subliminally, we understand how people’s designated roles and their positions within a hierarchy are inscribed in the colours they wear, as well as the types of clothing and their physical positions: standing at a machine; sitting at a table; giving directions while making a phone call.

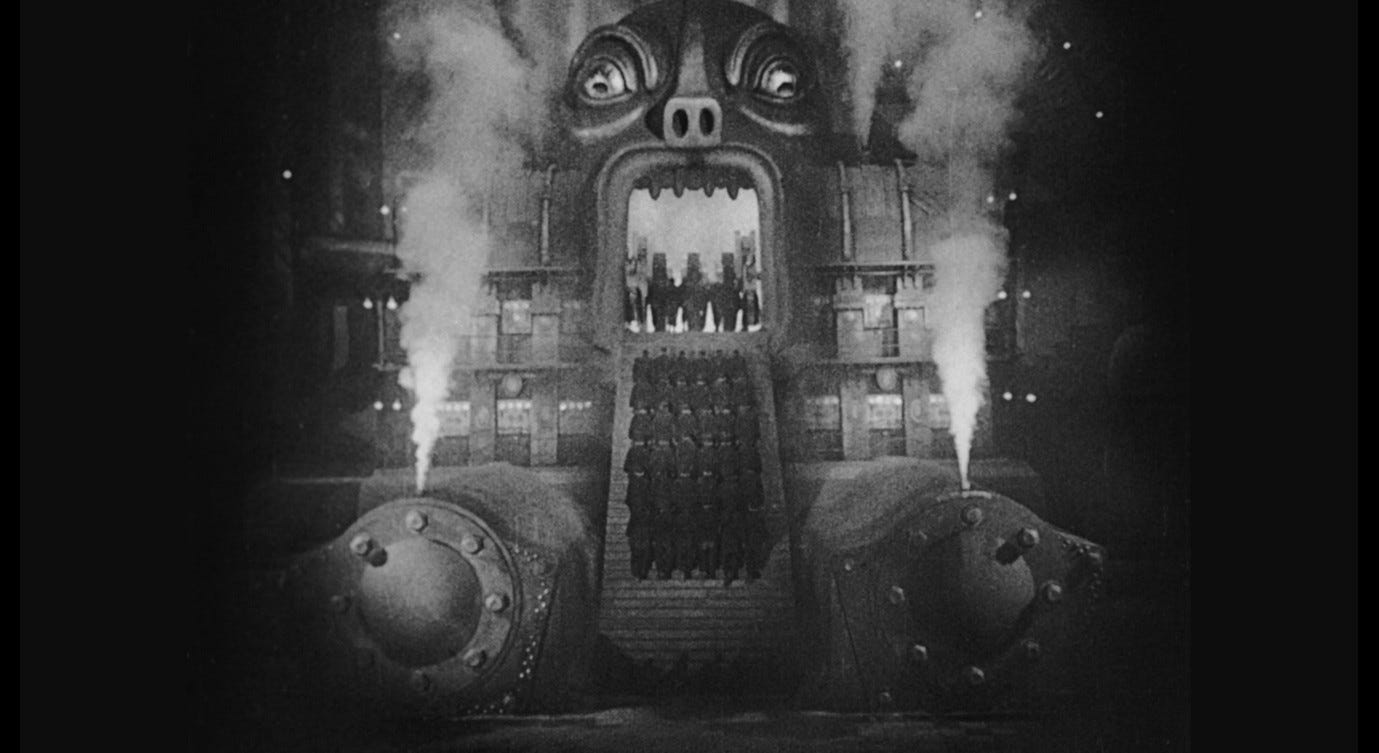

As Ugo makes his phone calls, he is connected with three colleagues in three different offices. As well as the hard-hatted Beltrami, we see two men who appear to work in administration, higher up the corporate ladder than Ugo. Their whitish-greyish or beige offices are clearly designed for white-collar work, but as with the two differently-blue spaces, there are distinctions here as well. One colleague’s office is grey and bleak.

Unlike in the blue offices, there is a large window, but the view is of two giant, spherical tankers. The man sits scowling at a desk covered in papers, with two drawers suspended underneath. He clearly writes his own letters and does his own filing. The screenplay describes him as an ‘impiegato’, an employee.3

The other colleague is called a ‘dirigente’, a director. He occupies a lighter, beiger office, and seems more at ease.

The camera is closer to him, meaning that his windows dominate the background and seem larger than the single window of the grey office. Outside we can see a row of immaculate trees, evidently planted there to complement the buildings and create a pleasant view. This manager stands, rather than sitting at his desk, as though Ugo’s phone call has caught him in the middle of dictating a letter to his secretary.

Victoria Kirkham sees the spherical storage tanks in the first office as representing ‘the new, progressive, industrial Ravenna,’ while the umbrella pines outside the second office are ‘reminders of Ravenna’s once unspoiled natural beauty and its cultural heritage [associated with the pineta], both of which are fast disappearing.’4 In Metropolis, all Joh Fredersen sees from his ivory-tower office is the bright, beautiful city over which he presides.

The executives in Red Desert see the machinery that makes the economic miracle possible and/or a remnant of the natural world that has been destroyed by that machinery. The distinction between these spectacles marks a distinction in the status of these men, but both views are meant to inspire and motivate. The ‘messaging’ is very clear: machines are beautiful, we still have umbrella pines, we never fire anyone, and the burners are under control.

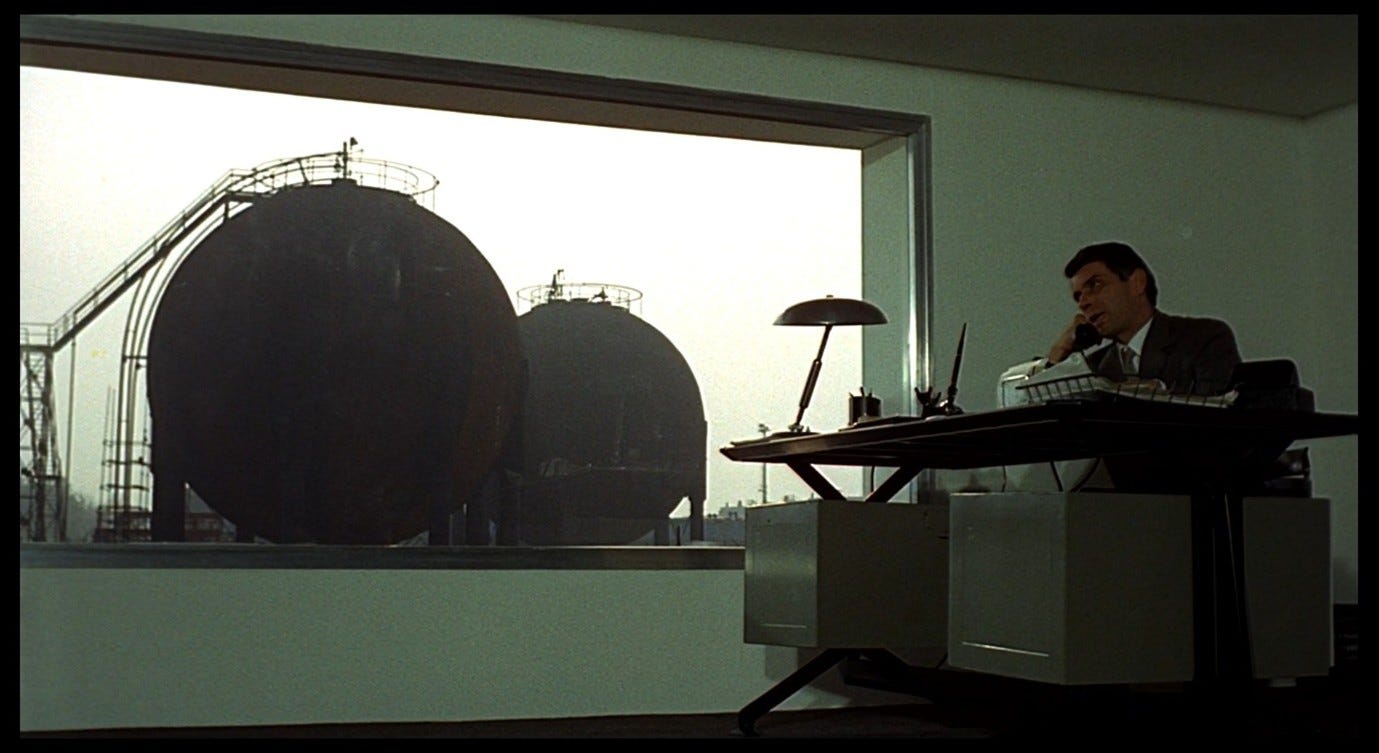

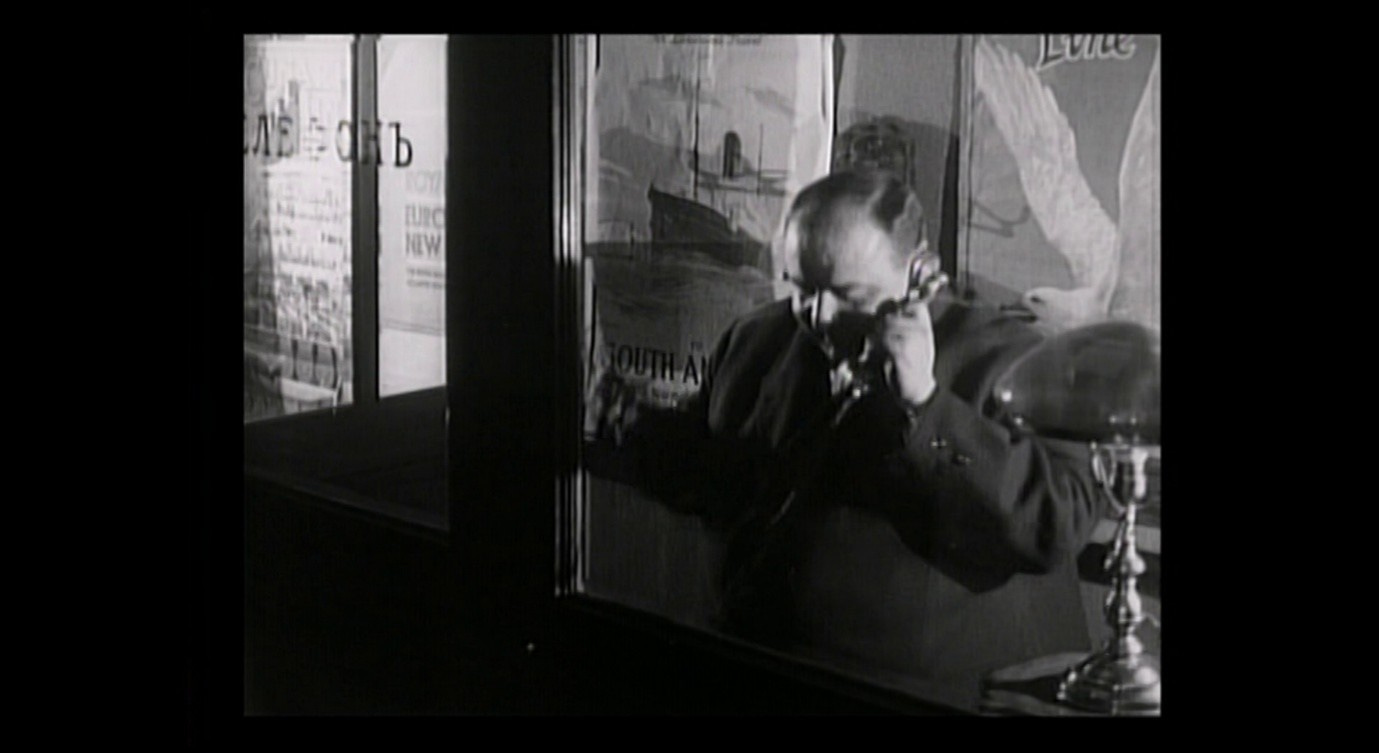

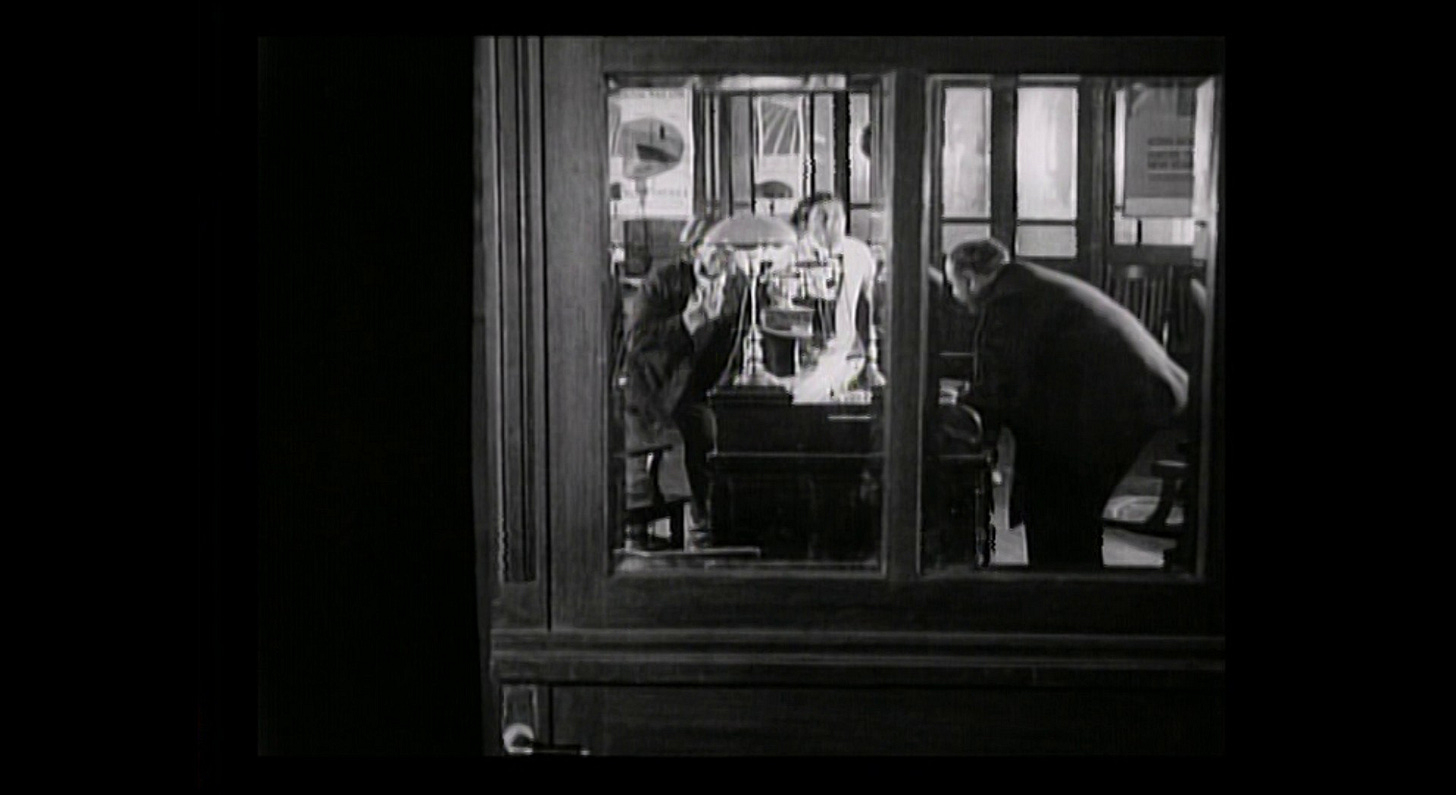

David Forgacs compares Ugo’s phone calls to the sequence in Eisenstein’s Strike when the trouble at the factory is reported, first to the director, then by him to his superior, and so on up the hierarchy.5 That sequence is a vicious satire on the capitalist pecking order. The pompous director rocks back and forth in his chair while his informants lean down awkwardly to give him the bad news; clearly, there is no question of them ever occupying the two empty chairs on the other side of the desk.

The director explodes with rage and everyone in his vicinity has to leap from their chairs – then he has to phone his boss to be shouted at in turn.

That boss and the next one up are both shown holding two phones to their ears: they are nothing more than conduits for this upward trickle of information, and the final boss has to ring a bell to demand yet more information (a heap of files delivered by another harassed underling).

As in Red Desert, the industrialists’ offices, seating arrangements, and phone manners reveal something about their status, but the overall message in Strike is that this is an abusive, dysfunctional, and ridiculous power structure. In one telling shot, we see the director and his underlings through two different window-panes; the camera is positioned inside the telephone booth the director will now enter to be yelled at by his superior.

Everyone is trapped in their own box, their own frame, and each frame is artificial - we want to see them all torn down. These men are completely alienated from their employees and from each other, quite unlike the heroic community of strikers (who interact in person and on a basis of equality). There is still something lightly comic about Ugo’s phone calls, not least because they achieve nothing except to validate what he has already told Corrado – that it will be impossible to recruit workers for his South American project like this – but in Red Desert the communications are efficient and amicable. If anything, this power structure seems a little too well-functioning.

In the world of Red Desert, your environment tells you something important about your place in the industrial hierarchy, and about how the company wants you to feel. In an interview with Jean-Luc Godard, Antonioni commented on what he called the ‘psychophysiology of color’:

[S]tudies and experiments have been done about it. The inside of the factory in the film was painted red; in the space of two weeks, the workers on the set had come to blows. The experiment was repeated, painting everything pale green, and calm was restored. The workers’ eyes need to be soothed.6

Those who work in the control room, tracking and adjusting temperatures, need to be calm and ‘in control’, so the calming blues help to set the right mood. The workers’ movements seem controlled but (unlike those in Metropolis) not coerced: the man at the back of the room side-steps from right to left and back again, not unlike Valerio side-stepping on the rails outside the factory, without any of the desperate urgency associated with the Moloch-machine. The overall mood in Ugo’s control room is one of muted confidence.

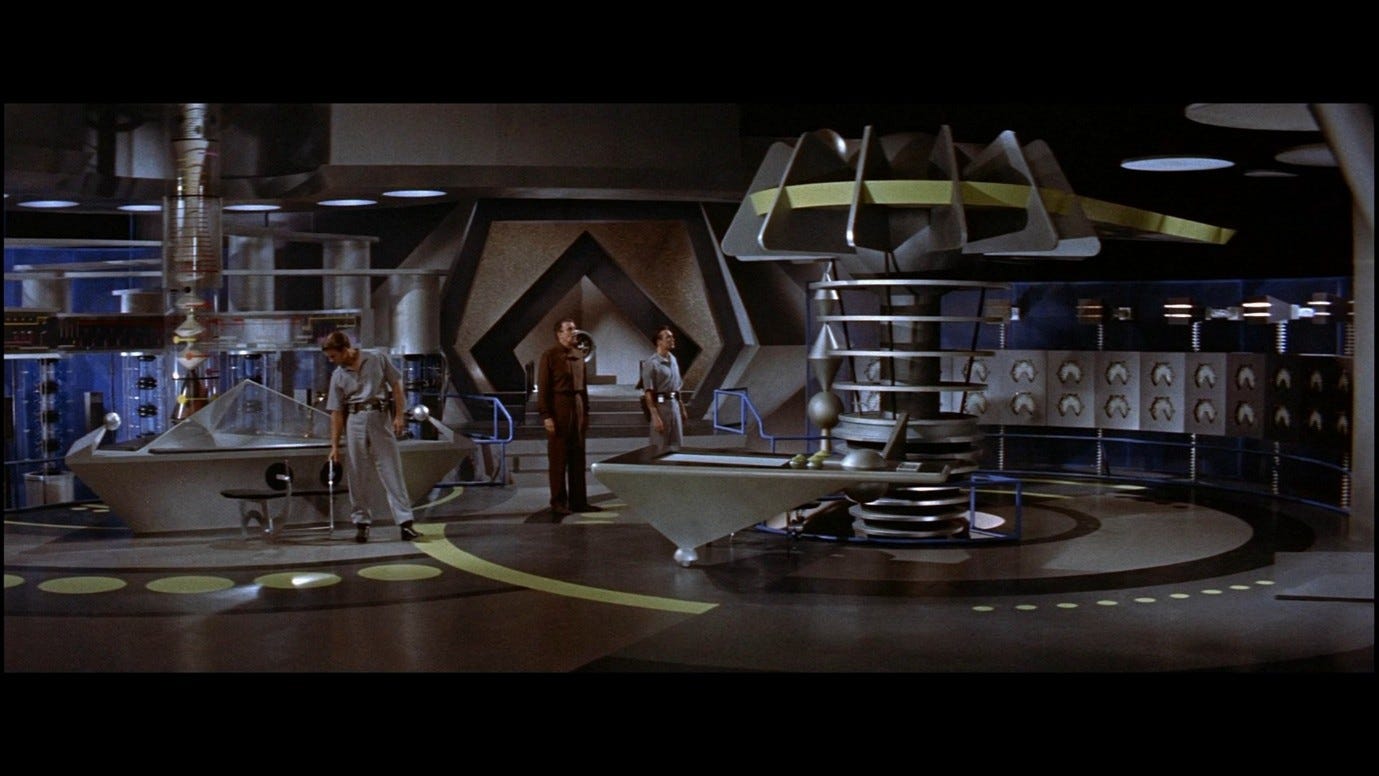

Murray Pomerance compares these factory interiors to the hyper-advanced control complex built by the Krell in Forbidden Planet:

It has the same look as this: gray walls, dozens upon dozens of levers and illuminated meters that glow in succession when the power level becomes high enough. Power as transparent, omnipresent, controllable, obedient.7

In that film, the differently transparent and differently omnipresent power of the id-monster turns out to be uncontrollable and disobedient. Like Rotwang and his evil robot in Metropolis, it represents the ‘step too far’, the hubris of trying to achieve these unnatural levels of mastery over the universe. The reactionary morality so often found in science fiction has no place in Red Desert, but there is still an equivalent ‘catch’ to this perfectly controlled environment, in the shape of Giuliana’s existential crisis.

As Ugo and Corrado leave the control room, we see a colourful mural on the wall outside. The camera lingers on it after the characters have left the frame, then we see the full mural, from an oblique angle, in the next shot.

The mural depicts two stars, with a background that may intended to represent the sky. We might expect to see white and/or yellow stars against a black background, but instead we see black stars against a white and yellow background. The stars themselves have some of their points chopped or rounded off. The upper star disappears into the ceiling, leaving a white trail behind it (like a shooting-star, perhaps).

This work of art has been inserted into this section of wall for a specific purpose. Like the calming blue tones of the control room, a work of art is presumably meant to have a positive emotional impact on employees. The very fact of its isolation gives a clue as to one of its likely purposes: to break up the sanitised, mechanistic character of this gleaming mezzanine. Corporate art lets employees know that this can also be a space for creativity, for aesthetically pleasing elements that are not directly related to the work being carried out.

Paradoxically, the relegation of this mural to a small patch of wall that would almost never be seen by anyone while they are at work – you see it briefly on your way into the control room – undercuts its message to the workers, reminding them how free of aesthetic distractions their actual workplace is. The images in the mural are suggestive of explosive energy, heat, and even pollution (the stars and sky turned black and yellow), rather than of a calming, natural scene (such as a blue sky above a green meadow). It is very much ‘of the factory’, not an escape from the factory.

In a 1979 interview, looking back on Red Desert, Antonioni said:

Factories are extremely beautiful. So much so that in many architecture competitions the first prize often goes to factories, probably because they are places that offer the imagination a chance to show itself off. For example, they can profit from colors more than normal houses can. They profit from them in a functional way. If a pipe is painted green or yellow it is because it is necessary to know what it contains and to identify it in any part of the factory.8

The camera in Red Desert treats the factories as though they were works of art. In Part 1, I said that the ‘eyes’ of the title sequence were like a visitor to an art gallery standing too close to the paintings, seeing only the dis-integrated smears of paint and not the coherent image they are collectively supposed to produce. But this spectatorial attitude also recognises the factories as ‘places that offer the imagination a chance to show itself off.’ The artist-architect has created something that can be treated like an abstract work of art, and that can be just as stimulating to the imaginations of those who look at it. I remember being especially struck by the beauty of the ‘factory tour’ sequence when I first saw Red Desert: the interplay between the colours of the different work-spaces, the carefully chosen camera angles, the way that different components of the factory are framed and re-framed, like aspects of a painting or sculpture we are looking at from different angles and distances.

However, when Antonioni talks about the beauty of modern factories, there is an ambiguity as to who benefits from this beauty, marked by the switch from ‘factories are beautiful and win prizes’ to ‘factories profit from colour in a functional way.’ Architects can express their creativity, but what does this mean for the workers? The red factory (allegedly) fills them with rage, the green one keeps them calm…but the rage factory might be the more beautiful work of art. In another interview, Antonioni described the advent of beautiful factories in terms of a (somewhat sinister) ‘invasion of colour’:

In Red Desert, we are in an industrial world which every day produces millions of objects of all types, all in color. Just one of these objects is sufficient – and who can do without them? – to introduce into the house an echo of industrial living. […] When, around the turn of the century, the world began to industrialize, factories were painted neutral colors – black or gray. Today, instead, most of them are brightly painted. […] Behind this invasion of color lie technical causes, but also psychological ones. The walls of the factories are colored not red, but light green or pale blue – the so-called ‘cool’ colors, on which the workers can rest their eyes.9

Those dark, de-humanising factories Antonioni refers to can be seen in Eisenstein’s Strike and Rossellini’s Europa ’51. Both are black-and-white films and their factory settings may have been colourful in real life, but we are clearly not supposed to see these as spaces designed to foster the employees’ wellbeing.

They are only a shade less horrifying than the Moloch-machine in Metropolis, and Irene Girard is a stand-in for the middle-class cinema audience who should be appalled by these conditions. Antonioni talks as though this problem were a thing of the past, now that factories are carefully designed to keep the workers content, to moderate their suffering just as the burners are moderated. But we may already sense a problem lurking behind the cool beauty of these blue/beige rooms.

At the start of Blue Collar, there is an overhead tracking shot of a production line in a car factory.

Paul Schrader says this was a deliberate reference to the overhead tracking shot at the beginning of Strike.10

This reference highlights the same historical contrast Antonioni referred to: we have gone from Eisenstein’s shadowy hell-hole to something that looks more like the Red Desert factory, with lots of calming greens and plenty of robots to help the humans do their jobs safely and efficiently. But in Blue Collar, it is immediately clear that this place is still a hell-hole. When Smokey is murdered towards the end of the film, he is killed by colour: trapped in an enclosed space with a car being spray-painted blue, he is not only suffocated but also painted to death.

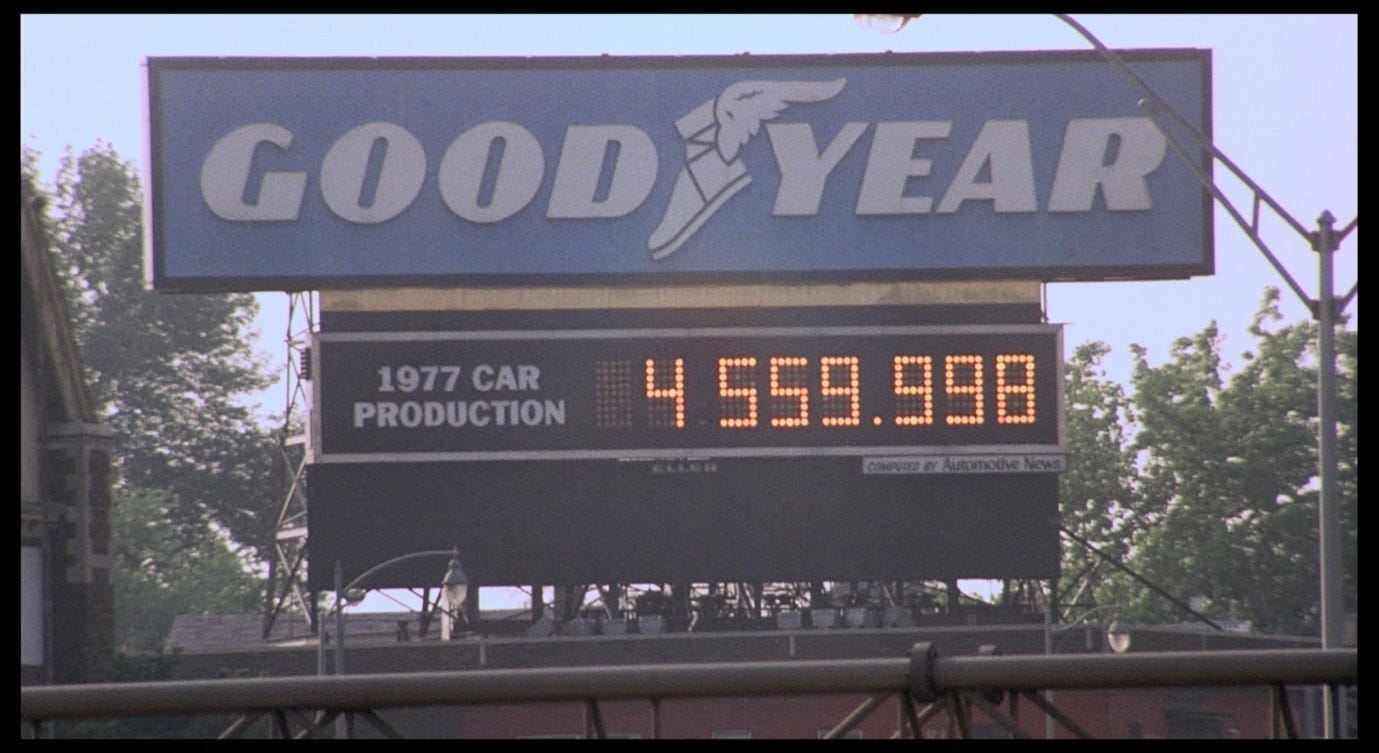

We cut directly from his blue-spattered corpse to a shot of the Goodyear sign, with a counter underneath celebrating the number of cars manufactured in 1977 (a measure of how ‘good’ the year has been). We cannot help noticing that the Goodyear logo is printed on a blue background.

In an article on the use of colour in films, Schrader cites Red Desert as ‘the film that changed everyone’s attitude toward color and completely freed its use from realism.’11 He quotes a passage from the Godard interview in which Antonioni expands on his point about the ‘invasion of colour’:

Even though we don’t realize it, our lives are dominated by ‘industry.’ And by ‘industry,’ I don’t just mean the factories themselves, but also their products. They are all over our houses, made of plastic or materials that, up to a few years ago, were totally unknown. They are brightly colored and they chase after us everywhere. They haunt us from the advertisements, which appeal ever more subtly to our psychology, to our subconscious. I would go as far as to say that by setting the story of Red Desert in the world of factories, I have got to the source of that crisis that, like a river, collects together a thousand tributaries and then bursts out into a delta, overflowing its banks and drowning everything.12

Blue Collar dramatises the crisis Antonioni describes here. Smokey’s death is incorporated into the colour-coded factory processes, and is written off afterwards as the result of negligence. The cut from the blue corpse to the blue corporate banner trains us to be haunted by this colour throughout the rest of the film. In the next scene, we see the Goodyear sign in the far background behind Zeke’s head.

Then, when he is trying to move on from Smokey’s death, we see blue-painted objects behind him, on a window sill in his house: remember Antonioni’s comment that ‘just one of these objects is sufficient to introduce into the house an echo of industrial living,’ or in this case an echo of industrial killing.

Later, when Jerry is being pursued by would-be assassins, his route is bathed in a ghostly blue light.

Modern industry uses greens and blues to keep the workers calm, but really it uses them to conceal its crimes. In the final freeze-frame, we hear Smokey’s voice from beyond the grave: ‘They pit the lifers against the new boys; the young against the old; the black against the white. Everything they do is to keep us in our place.’ The screen is blotted out with bright red, against which the end-credits roll.

Blue Collar portrays a blue-green hell, revealed in that final fade-out as a living, bleeding, red desert.

Human Resources offers a less stylised picture of factory life, and one in which the use of colour is not ‘completely freed from realism,’ to use Schrader’s term. This late-1990s industrial space is perfectly clean and designed for optimal safety and efficiency, but its friendly colours are as bogus as its friendly managers.

As Murray Pomerance says of the colours in the Sunny Dunes sequence in Zabriskie Point:

This is the color of a sequestered environment, produced through commercially processed dyes that borrow from nature but transform natural chemistry in order to seduce the always mobile human eye in an environment of total transformation, provisionality, rhetorical shifting, and bargain-hunting.13

It is remarkable how much Pomerance’s description of the commercial environment applies also to the industrial one: the factory that does the processing is colour-coded just as manipulatively as the TV adverts that sell the products.

Franck, taking on an HR role in the factory where his father still works on the production line, slowly realises how the white collars are pitted against the blue. His desire to mediate between them (like Freder in Metropolis) is partially symbolised by the white-blue checkered shirt he wears – more blue than white, unlike Ugo’s – as he hands out his ill-fated questionnaire, not realising how this will bring about his own father’s redundancy.

One of the workers, Alain, describes his first impression of the factory:

My first day in the workshop, when I saw everyone in blue, covered in grease, bent over their machines, with all the noise, I said ‘Fuck, this is hell!’ I just wanted to get out. Then the foreman came. He put me on a machine and told me to work.

Alain is sceptical about Franck’s desire to improve working conditions. He is gently pointing out that Franck is a white-collar tourist in a world that Alain (and Franck’s father) have known intimately for years. In the film’s final scene, as Franck prepares to return to Paris to find a new job, he asks Alain, ‘So when are you leaving? Where’s your place?’ The camera tracks around them until Alain becomes invisible, blotted out behind Franck.

Despite the small acts of rebellion against the powers that be, the systemic injustices remain unresolved, just like in Blue Collar.

Although Red Desert is not angry about modern industry in the way that Blue Collar and Human Resources are, it foreshadows the way those films play with the ambiguity of cool colours and cool managers. When so much work goes into controlling both the industrial spaces and the employees’ perceptions about them, and when that work is made visible, it is hard not to think of the abuse and exploitation that are being enabled by this propaganda. Later in Red Desert, when Corrado briefs the workers for the Patagonia trip, we will glimpse a small sample of disgruntled employees, but ones who have still very much been ‘kept calm’ and subdued by the prevailing blues of their environment.

It has to be said that Red Desert is more interested in Giuliana’s plight than that of the workers, and its focus on a bourgeois existential crisis is no doubt indicative of Antonioni’s limited perspective. But as Laurent Cantet said about the relationship between Human Resources and his next film:

Vincent in Time Out experiences the same alienation as the workers in Human Resources – even if he’s not an industrial worker and the reason for his alienation is not as obvious. You don’t see him on an assembly line working with a noisy machine and becoming exhausted. But his dilemma is the same – his job doesn’t correspond with his needs.14

This conflation of middle- and working-class experience is also open to critique, but it is important to understand that Antonioni and Cantet are drawing these connections between seemingly disparate forms of industry-related alienation.

The ‘factory tour’ sequence in Red Desert makes it clear that colours have several functions, signifying people’s roles and statuses, and creating (in principle) an atmosphere conducive to good working conditions. As we follow Ugo and Corrado into the factory’s lower depths, we see a range of colour-coded pipes and railings. These colours – greens, reds, blues, and yellows – are intended to communicate specific meanings, although these meanings are not spelt out for us. In some cases, we might assume that the colours indicate something about the substances being conveyed through the pipes, or about the level of danger in a particular area. As in: there is no reason to panic if the green pipe is damaged, but if the red one springs a leak, we all die.

It says something about the relationship between this tank and the pipe coming out of it that one is blue and the other is yellow, and we probably need to understand this relationship before we start playing with the valves.

However, there is a tension between our sense that this is a very rational, regulated world and our inability to read it. We traverse the outer and inner industrial spaces in a way that makes them legible to us up to a point, but illegible and disorienting beyond that point.

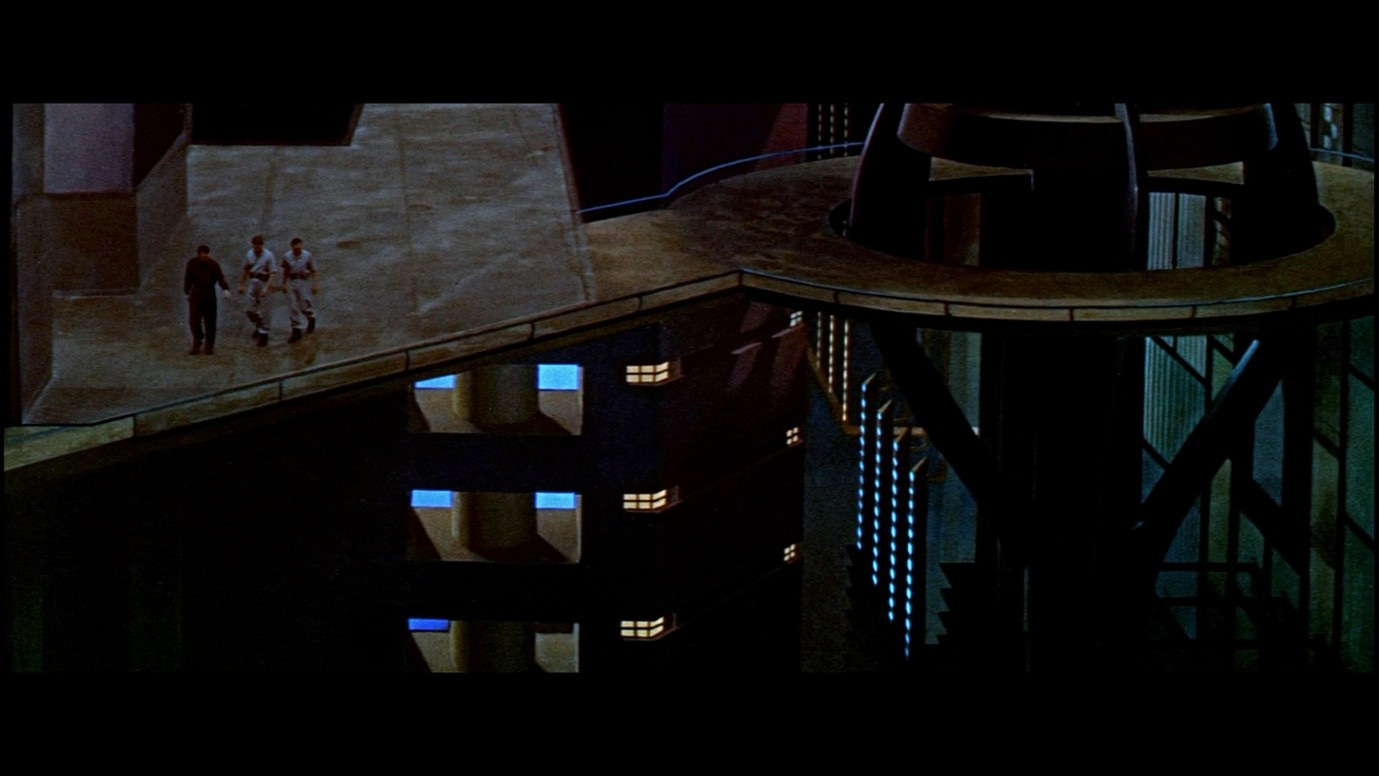

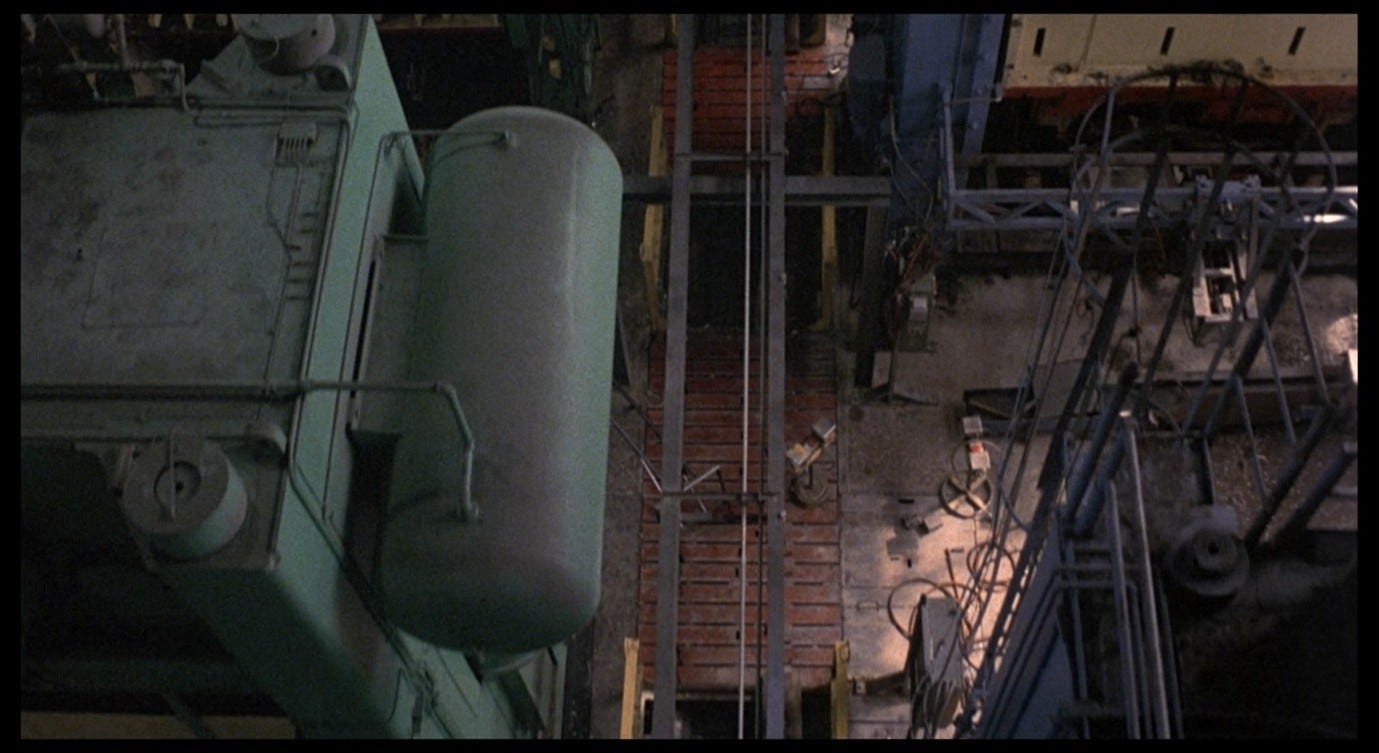

Consider the very strange shot in which we see Ugo and Corrado from above through a floor grate.

We are about to see Giuliana descending some steps to find Ugo, so it would make sense if the through-the-floor shot represented her point of view: we might see her searching the factory, she would look down and see Ugo through the grating, then she would find the nearest stairs and descend to his level. This could be an elegant way for the film to transition back to her perspective.

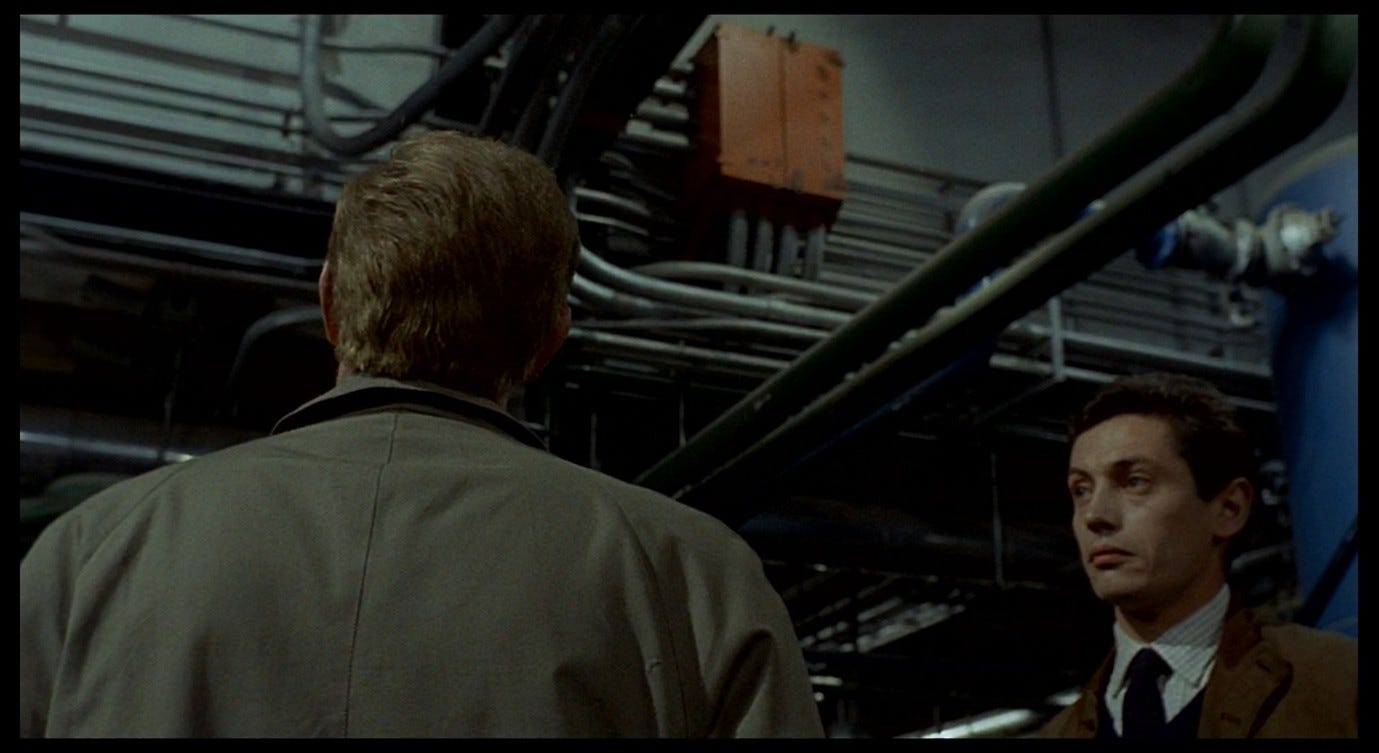

But this is not what happens. We are with Ugo and Corrado among the pipes. Corrado takes in his surroundings and Ugo watches him doing this, with perhaps a hint of pride on his face.

We cut to the floor above them and see, through the floor-grate, the two men walking around the factory.

The camera is static and much closer to the floor than a person would be. Only after this shot do we cut to Giuliana descending the stairs, and there is no apparent causal relation between these images.

When we see the two men through the floor, Corrado briefly looks up in our direction, but clearly does not see anyone up here – we are not about to cut to a reverse-shot of another person.

Rather than seeing through Giuliana’s eyes, we are seeing through a mechanical eye like that of a surveillance camera, from a position so close to the floor that we seem to be embedded in what, for Corrado, is the ceiling. It feels like an entity is keeping watch from a secluded space, unseen and inaccessible to the human characters. There is something mysterious and unsettling about this through-the-floor shot. We do not know where we are, or why we are there, or what is behind us, looking through the camera lens.

There is a similar through-the-grate image in The Scar, as we watch Bednarz and his colleague ascend the steel-mesh stairwell to attend a (literally and figuratively) high-level meeting with powerful men in suits.

We see them shaking hands, again through the grate but now from below.

If the first of these images maintains a sense of documentary realism – Bednarz, unlike Corrado, sees the camera looking down at him and greets it as he climbs upwards – the second is more like those strange, abstract moments that punctuate the rest of Kieślowski’s film. The juxtaposition of these two shots conveys Bednarz’s sense of being caught in an untenable position, between senior management, the workers, and the inhabitants of the town who are affected by the new chemical plant. Which side is he on, which level does he occupy, and who is looking up and/or down at him? Like Franck in Human Resources, he will struggle to mediate between these conflicting points of view.

Millicent Marcus reads the metal-grate shot in Red Desert in terms of Antonioni’s ‘taste for abstraction’:

Antonioni tends to break up his shots into small visual cells, as he does in the factory, looking down at his two male protagonists through a grating, or using split compositions to divide the mise-en-scène. It is through abstraction that Antonioni is able to suggest connections among otherwise disparate settings – settings that would conjure up antithetical expectations in the conventional cinema.15

We could think about ‘connections among disparate settings’ in several different ways. The floor-grate image in Red Desert plays with the liminality of the floor-that-is-also-a-ceiling. It asks whether this factory-for-humans is also, and perhaps more truly, a factory-for-robots, for mechanical eyes that see like surveillance cameras. When we find out the camera was positioned on the same floor as Giuliana, just before she came down the stairs looking for Ugo, we realise the floor-grate image was also drawing an uncomfortable connection and contrast between the camera that inhabits the protagonist’s perspective and the camera that operates independently from her (though physically nearby).

We might also think of connections between seemingly disparate crises: white-collar, blue-collar, political, economic, and existential. The factory exteriors and interiors, the workers, the executives, and the roving camera-eye that sees them all in calculatedly abstracted ways – all these components in Red Desert amount to a kind of objective correlative expressing Giuliana’s plight, and she in turn becomes a walking amalgam of those disparate crises. Everything we see and hear in Red Desert is part of what ‘happens’ to Giuliana, and everything she says and does refers in some way to the people and things around her, just as it bleeds into the conflicts portrayed in other films about people whose needs are in conflict with their environment.

Next: Part 8, The cloud of steam.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Billard, Pierre, ‘An Interview with Michelangelo Antonioni’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 141-147; p. 145

Masłoń, Sławomir, Secret Violences: The Political Cinema of Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960-75 (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2023), p. 96

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 438

Kirkham, Victoria, ‘The Off-Screen Landscape: Dante’s Ravenna and Antonioni’s Red Desert’, in Dante, Cinema, and Television, ed. Amilcare A. Iannucci (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), pp. 106-128; p. 124

Forgacs, David, Commentary track, Red Desert (Blu-Ray, BFI, 2008)

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; p. 294

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 81

Tassone, Aldo, ‘The history of cinema is made on film’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 193-216; p. 203

Maurin, François, ‘Red Desert’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 283-286; pp. 283-284

Schrader, Paul, Commentary track, Blue Collar (Blu-Ray, Indicator, 2018)

Schrader, Paul, ‘Color’, Film Comment 51.6 (2015), pp. 52-56; p. 55

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; p. 289

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 183

Schulman, Peter, ‘“Fragmegration” of Identity in Laurent Cantet’s Ressources Humaines and L'Emploi du Temps’, Cincinnati Romance Review 43 (2017), pp. 90-106; p. 91. Quoting Porton, Richard, and Lee Ellickson, ‘Alienated Labor: An Interview with Laurent Cantet’, Cinéaste (Spring 2002), pp. 24-27; p. 24

Marcus, Millicent, Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), p. 192