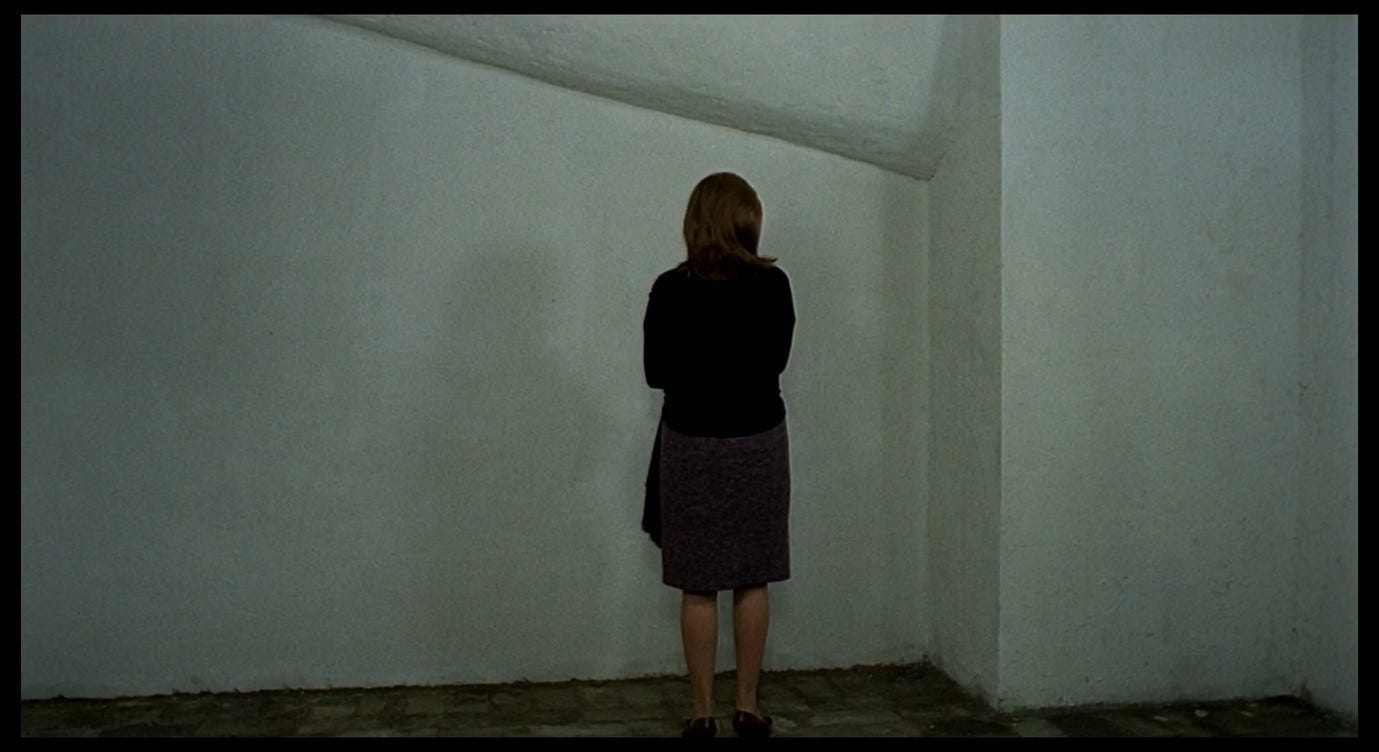

Corrado, paying a visit to Giuliana’s ‘indecorous’ shop, finds her occupying an alarmingly bare white space. The only objects in the room are a stool, a pile of Tintal paint-cans, a telephone, and a dangling bare light-bulb. The phone and the light are (like the wires extending over the street) conspicuously 20th-century objects in this archaic setting, and they seem recently installed but still not properly integrated. As such, this interior set feels of a piece with the exterior street scenes discussed in parts 12 and 13: it is hard to imagine anything modern finding a comfortable home here. And sure enough, Giuliana has hardly begun to set up her shop.

Clelia in Le amiche, with her strong work ethic developed during her working-class upbringing, applies herself vigorously to the task of establishing a new salon in Turin. Her practicality makes for a stark contrast with the frivolity of her Turinese friends, who have never worked a day in their lives. In the Cesare Pavese novel upon which Le amiche is based, Clelia (the narrator) makes a withering comment about the social scene she finds herself plunged into:

[I]t was funny but in Turin I had to avoid people. There were so many painters, so many vain, inflated nobodies, so many musicians – a new one everywhere you turned, not even in Rome were people so continuously on holiday. And there was Mariella, too, who wanted to act at all costs. You’d have thought there’d never been a war.1

Giuliana in some ways resembles Rosetta from Le amiche, a person shaped by a social milieu that has not equipped her for the world of work. No doubt this is one of the reasons why Ugo finds it inappropriate for the wife of a prosperous industrialist to set up a small business: a woman of Giuliana’s (or Rosetta’s) station should not do such things, and indeed should not be able to do such things.

However, Giuliana’s inertia goes beyond that of Rosetta, who was literally unable to show up for work. It seems that Giuliana often shows up and spends a lot of time ‘at work,’ but that she fails to accomplish anything. We see her trying to decide on a colour-scheme, on the items to be sold, and on the next action she needs to take, but with each task she stalls and lapses into despair.

The first thing she does, upon re-entering the shop with Corrado, is to inspect the walls and ceiling, upon which Rothko-like blocks of paint have been daubed. These colour samples are restricted to one corner of the room, making the colours feel ‘cornered’ by the prevailing whiteness. Colours are being tested out in this corner but they are afraid to venture beyond it.

Giuliana, evidently resuming a conversation she was having with herself before Corrado arrived, says ‘Perhaps sky-blue [celesti] is best.’ She uses the plural form, ‘celesti’, and when Corrado asks for a clarification she explains that she is considering sky-blue as a colour for the (plural) walls [le pareti]. She goes on to say that she favours green for the ceiling [il soffitto verde], because these are ‘cool colours that will not disturb.’ Again, Corrado has to ask what she means – what will not be disturbed? – and Giuliana specifies, ‘Yes, the things that are sold, the objects.’ She is as hesitant to disclose information as she is to spread colour over these surfaces.

Before it became Il deserto rosso, this film was going to be called Celeste e verde, but Antonioni abandoned this title because ‘it seemed a little too attached to the issue of colours.’2 He refers to the same colour combination when talking about modern factories, whose walls ‘are coloured not red, but light green or pale blue – the so-called “cool” colours, on which the workers can rest their eyes.’3 In another interview, he described the effects of industrial colours in more visceral terms:

The inside of the factory in [Red Desert] was painted red; in the space of two weeks, the workers on the set had come to blows. The experiment was repeated, painting everything pale green, and calm was restored. The workers’ eyes need to be soothed.4

Indeed, the ‘red’ title is the antithesis of the ‘blue and green’ one. Celeste e verde are the colours Antonioni sets in opposition to rosso, and their associations with the sky and ‘verdant’ nature contrast with the desert where ‘there are few oases left,’ coloured red by the blood and flesh of its victims. The latter seems more tonally in tune with the bleakness and emotional violence of the finished film, and as Antonioni implies, the idea of a ‘red desert’ is more broadly suggestive because it is less exclusively focused on the idea of colour. First and foremost, we are looking at a desert, then we notice it is red, just as we see the fruit-cart in the Via Alighieri and then notice it is grey.

If this film were called Celeste e verde and were unchanged in every other respect, Giuliana’s comment would draw more attention to itself as a defining moment. It is worth spending some time in this alternate reality and considering what the film’s abandoned title might have meant.

Giuliana is attempting to create a space that will have a certain effect, specifically a cooling, non-disturbing effect. As we have seen, she finds her environment extremely disturbing. She has a tendency to over-heat and become feverish in response to it. The screenplay comments on how thin her clothes are in the present sequence, given how cold the weather is,5 and Giuliana is noticeably indecisive about whether she wants her shawl wrapped around her, whether she wants to put her coat on, and whether she wants to sit near the roasting chestnuts. She likes the cold, just as she likes cool colours: the state of cool non-disturbance is something she aspires to. In this light, the title Celeste e verde would conform with a tendency we see in some Antonioni film titles, which refer to something that is desired by the characters but is ultimately unattainable.

Antonioni’s first feature film, Story of a Love Affair [Cronaca di un amore], is a good example, because it could just as easily have been called Story of a Love Affair that Never Existed [Cronaca di un amore mai esistito]. The latter is the title of a short story in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber, adapted as the first episode in Beyond the Clouds. The titular ‘amore’ in the earlier film disintegrates at the end when the so-called lovers drift apart, despite (or because of) the removal of the inconvenient husband who supposedly stood in their way. In retrospect, the title seems ironic.

This love story chronicles the undoing or negation of love, and the indefinite article in the title figures the ‘amore’ in question as a discrete, finite, material thing whose birth and death can be told from start to finish: it is a single ‘amore’, and not in a way that marks it as special or unique. The main characters, Paola and Guido, are ostensibly pursuing ‘love’ as something that will give meaning to their lives, but ultimately they find that this love, and by association their lives, are meaningless.

In Le amiche, Clelia eagerly seizes the opportunity to make friends with the women she meets in Turin, and the film revolves around the relationships between these titular ‘girlfriends’. In holding up the concept of female friendship, which the Italian language figures as a kind of ‘love’, the film deviates from the coldness of the source novel. Pavese’s title, Tra donne sole, is usually translated as Among Women Only, but also plays on alternate meanings of ‘sole’ such as ‘single’, ‘alone’, or ‘lonely’. The novel’s bleak tone is aptly channelled through its cold-blooded narrator-protagonist. The film makes Clelia (and Rosetta) warmer and more emotional, more fixated on the goal of forming romantic and platonic love-connections. Le amiche thus becomes a more pointed commentary on how people attempt to love each other. We are invited to reflect on the concept of ‘girlfriends’, to ask what such friendship consists in, and ultimately – as in Story of a Love Affair – to regard the title ironically, as we watch the circle of friends disintegrate and turn against each other. In the climactic scenes, Clelia denounces the first of her supposed ‘amiche’ as an ‘assassina’, then has no contact with any of the other girlfriends, chooses her career over her lover, and departs on a train to Rome without anyone to see her off. Le amiche – who needs them?

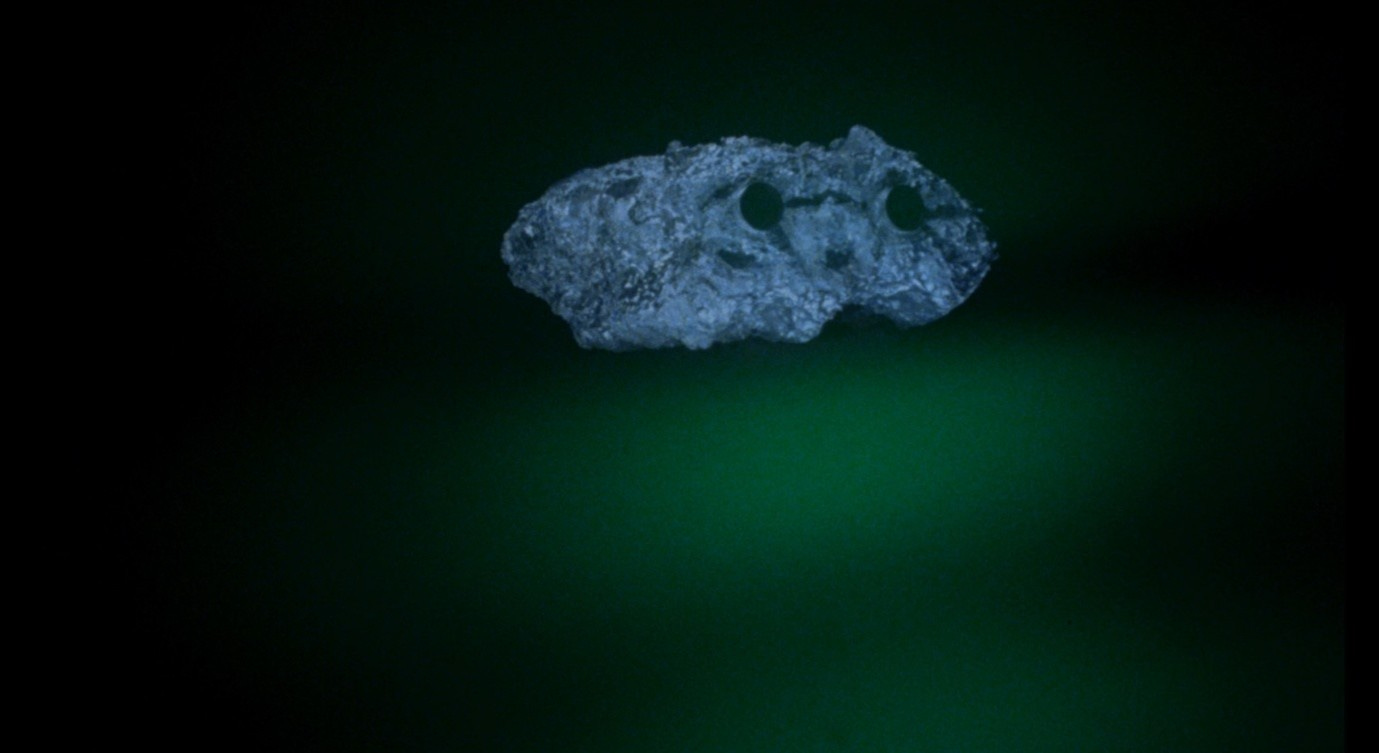

The title of L’avventura signifies both an ‘adventure’ and an ‘affair’, both of which are much sought after by the characters, and both of which turn out to be crushing disappointments. The boat trip to Lisca Bianca is supposed to be a fun outing, but even before Anna’s disappearance the holiday-makers seem to be going through the motions. No viewer can fail to sympathise with Anna when she cries out ‘Uffa che noia!’ and hurls herself into the sea at a particularly tedious moment. Her companions are alarmed by her disinhibited protest against the noia they have all been quietly putting up with.

Later, after she disappears definitively, the search for Anna is itself a kind of adventure and might have made for a suspenseful pursuit-narrative in a different kind of film. But it is undertaken with a depressive listlessness and ultimately abandoned. With regard to the other kind of ‘avventura’, all the characters find themselves pursuing affairs of one kind or another, with a strange mix of absolute devotion (these are high-stakes affairs that occupy all their time) and impulsive carelessness (these affairs are transient and disposable). Everyone is looking for adventures. Everyone is fed up with adventures. Somehow, these two facts are mutually inclusive.

In Blow-Up, the central character uses his camera to record reality, but also to create art in the form of his own carefully structured photo collections. When he blows up the pictures of Maryon Park, he thinks he has discovered something incredible, and – although this is not spelt out – there is a sense that for him this represents a professional and creative apotheosis. The blow-up of the title reflects this aspirational mood, referring as it does to the capacity of a tiny piece of film to expand and reveal profound truths. Here again is that ‘secret and reciprocal creative satisfaction, a shared sense of the tragic revelation of truth,’6 which Antonioni seemed to experience when filming the scene with the fruit-seller in Red Desert. But in Blow-Up, the pictures and the dead body disappear, and the blow-up that is left behind reveals nothing without the context of the other pictures: it becomes a meaningless abstraction, as does its creator. The final shot makes the photographer a tiny figure against an empty green background, then fades him out of the picture. The quotation marks around the title in the final image seem ironic when set against this defiantly un-blown-up long shot from which the only identifiable figure has been removed.

The unspoilt desert in Zabriskie Point becomes an Edenic place of refuge for the similarly unspoilt young Americans, escaping from the corruptions and oppressions of civilised society. Here is a place where they can communicate, be themselves, and engage in free love. But the desert orgy quickly turns melancholic. The youths who suddenly appear alongside Mark and Daria seem like ghosts conjured from the rocks, their bodies becoming pale as they are coated in sand (like the greying Via Alighieri). As Sam Rohdie puts it:

The figures become in their dance of love like the desert, like its sand, chalky white, as if ghosts. […] At the moment when the image is most narratively empty and seems to revert to a purity of abstract form, at that moment it becomes most visually full. It is as if the dead, the void, have come alive.7

Arguably, the scene suggests the opposite: that these alive and fulfilled figures become dead, become a kind of desert-void. Jerry Garcia’s music shifts into an anxious minor key as the orgy fizzles out. The couples are arranged in a final tableau that stresses the distance between them, like a de Chirico painting, then we see desolate vistas covered in sand-clouds that resemble the Ravenna fog in Red Desert. Daria looks around anxiously; moments later, she is asleep and lost in the sand-cloud.

Soon afterwards, she and Mark go their separate ways into separate kinds of oblivion. ‘I always knew it’d be like this,’ says Mark. ‘Us?’ asks Daria. ‘The desert,’ he replies. Both Zabriskie Point and this fleeting relationship are as liberating and as futile as they were expected to be.

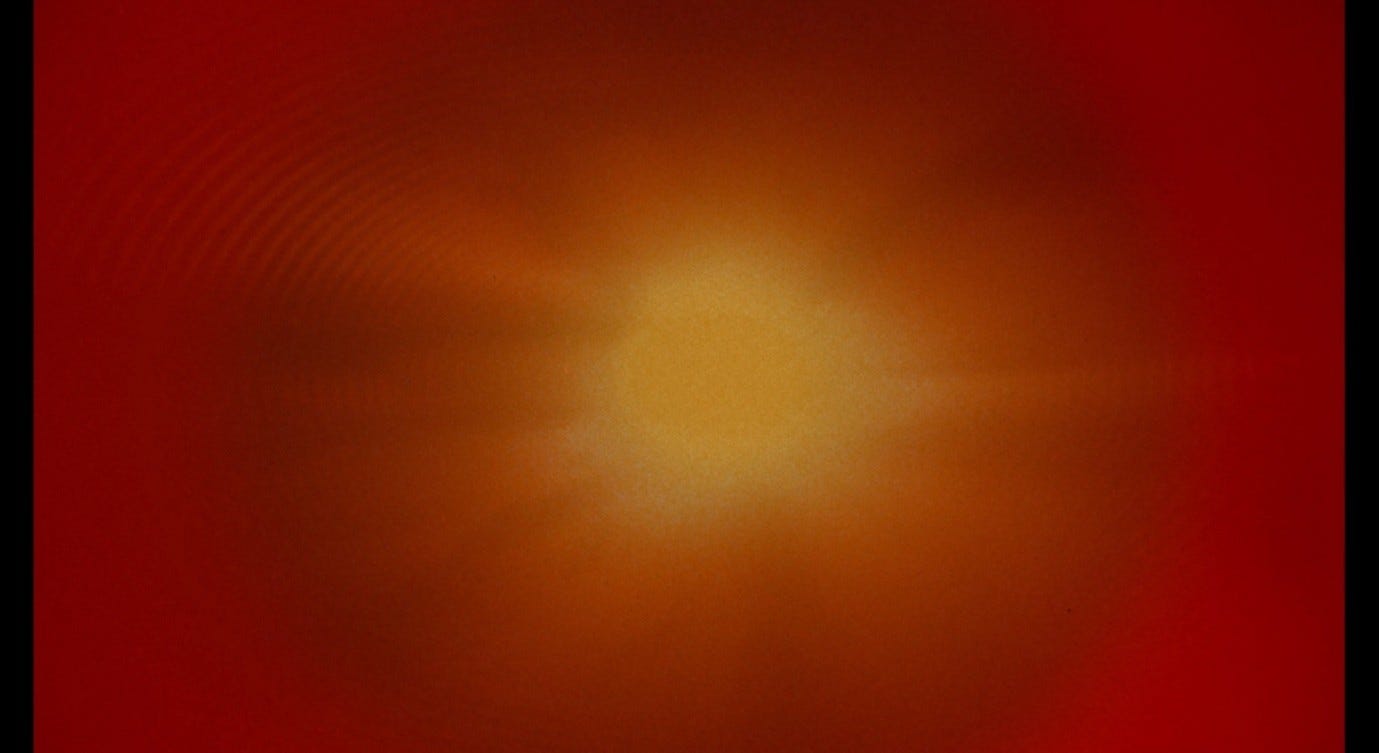

Identification of a Woman describes a film director’s languid efforts to ‘identify a woman,’ either by finding the female protagonist for his next film or by getting to know his girlfriend well enough to have a meaningful relationship with her. Neither project works out and he ends up alone in his study, planning a new film in which the sun will replace the woman as the source of life’s meaning and the object of artistic and scientific study. The new film could be called Identification of the Sun, but even this project is thrown into question by the nephew’s sceptical and unanswered question, the final line of the film: ‘And then [E dopo]?’ Niccoló removes his sunglasses and closes his eyes as he imagines the sun-voyage. The exhaust ports of the spaceship come to resemble two eye-holes through which the light of the sun is visible, until we seem to be looking at the silhouette of an eye-mask (and a ghost of Niccoló’s sunglasses) fading away beside a pulsating, annihilating ball of light. What can be seen here, let alone identified? Is there any room for ‘and then’ after this?

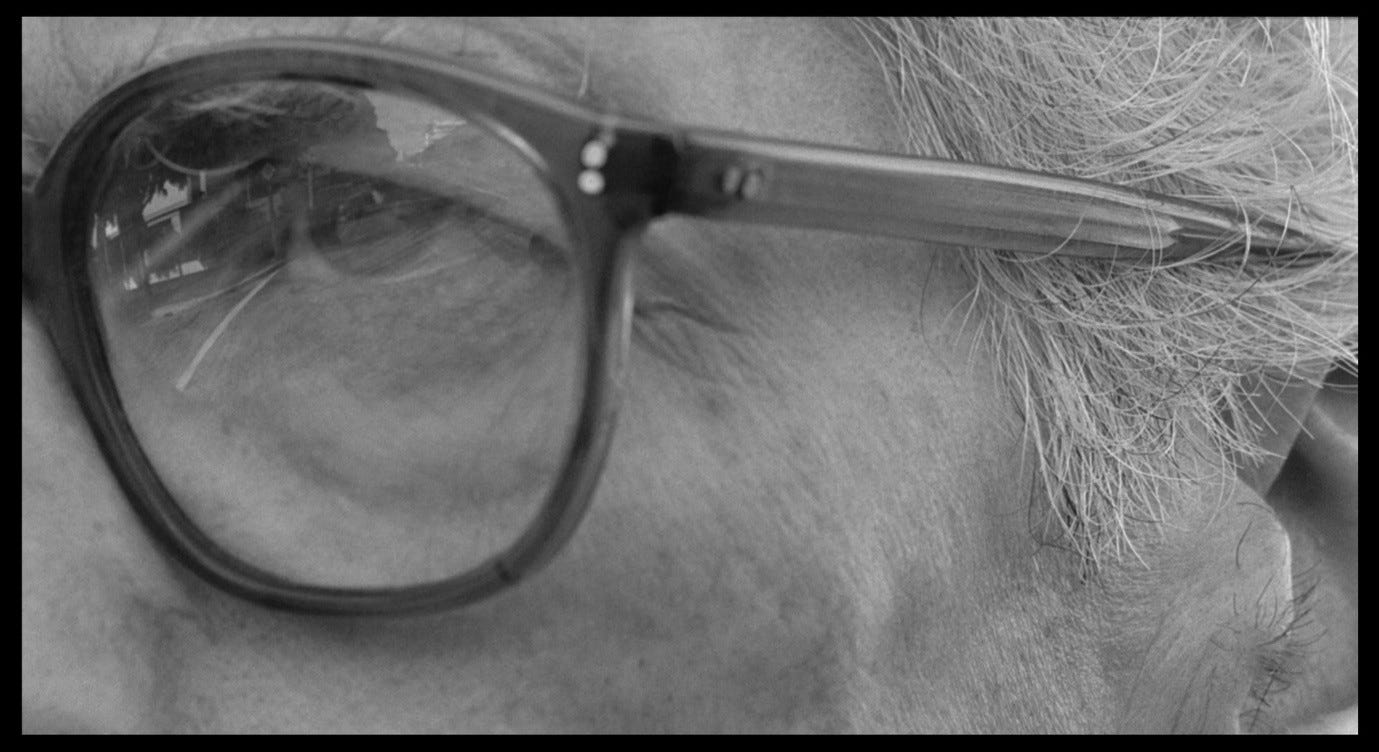

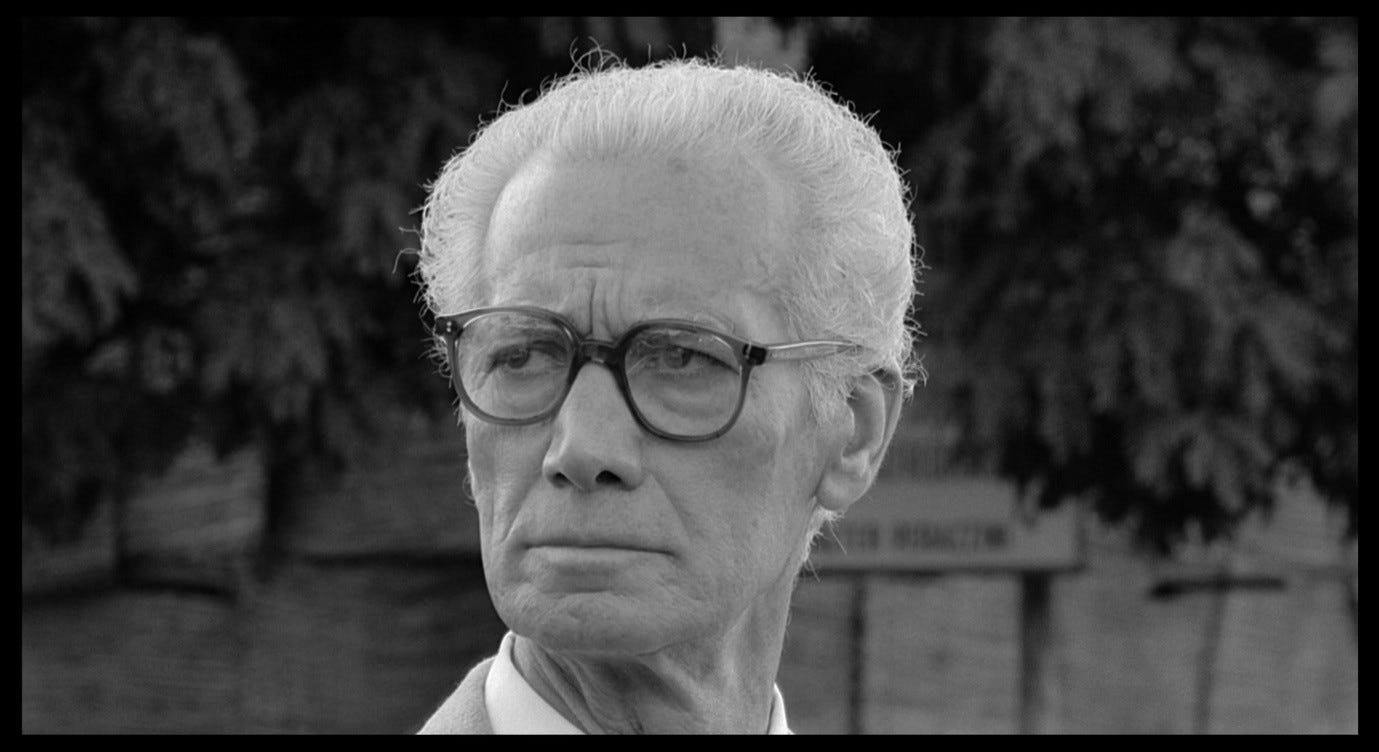

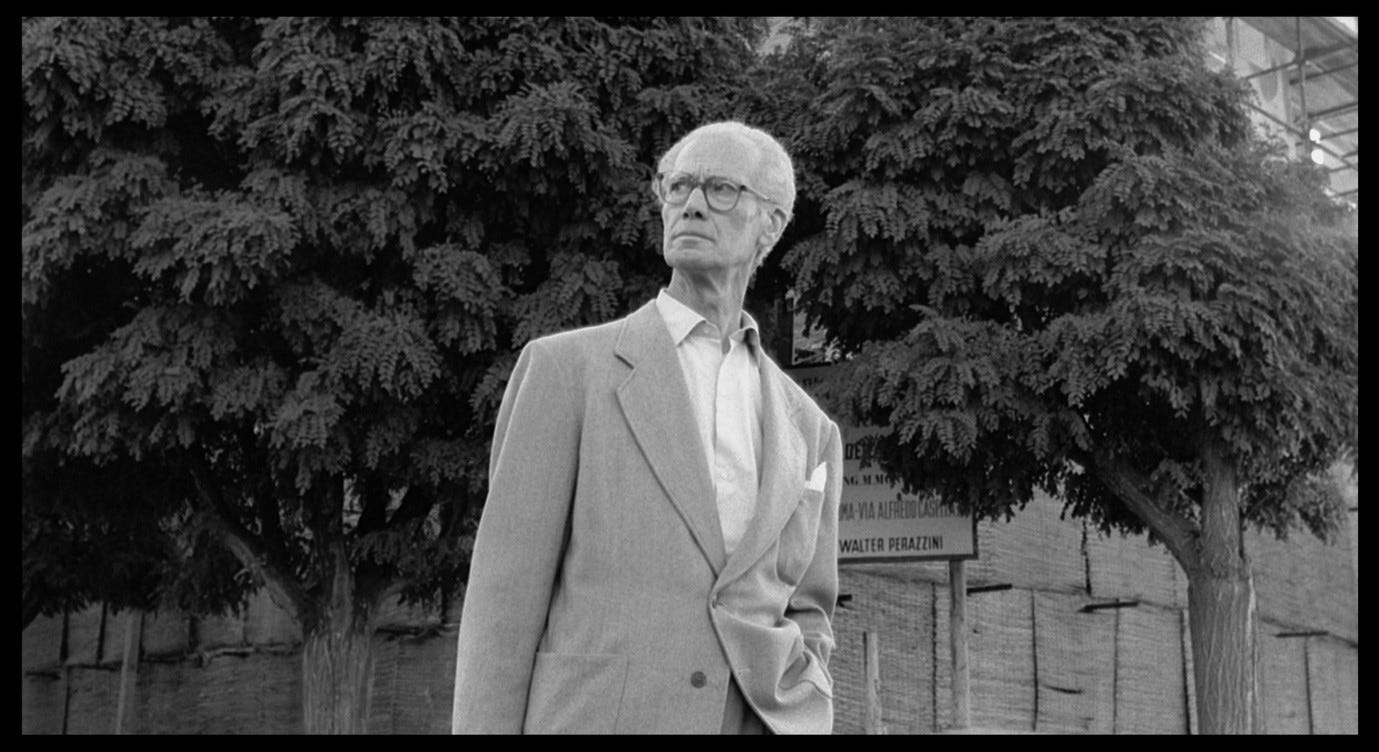

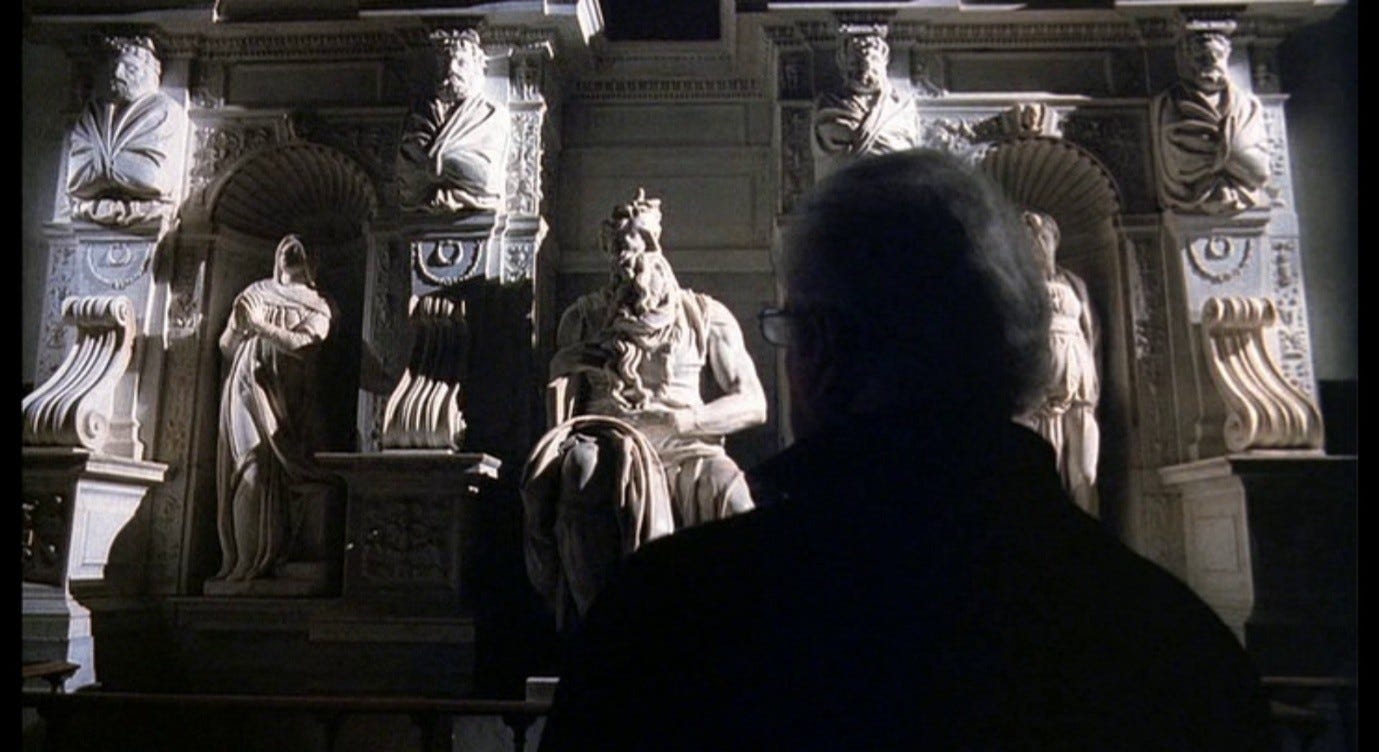

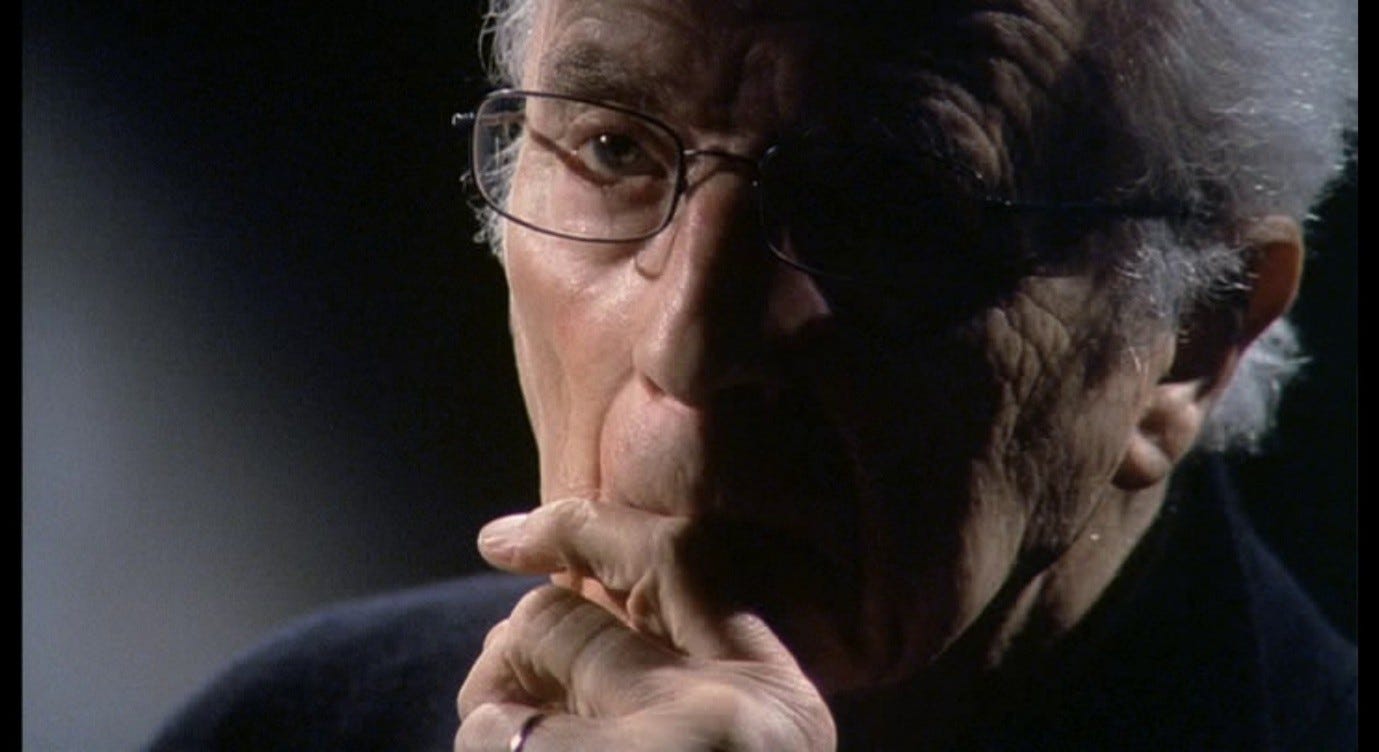

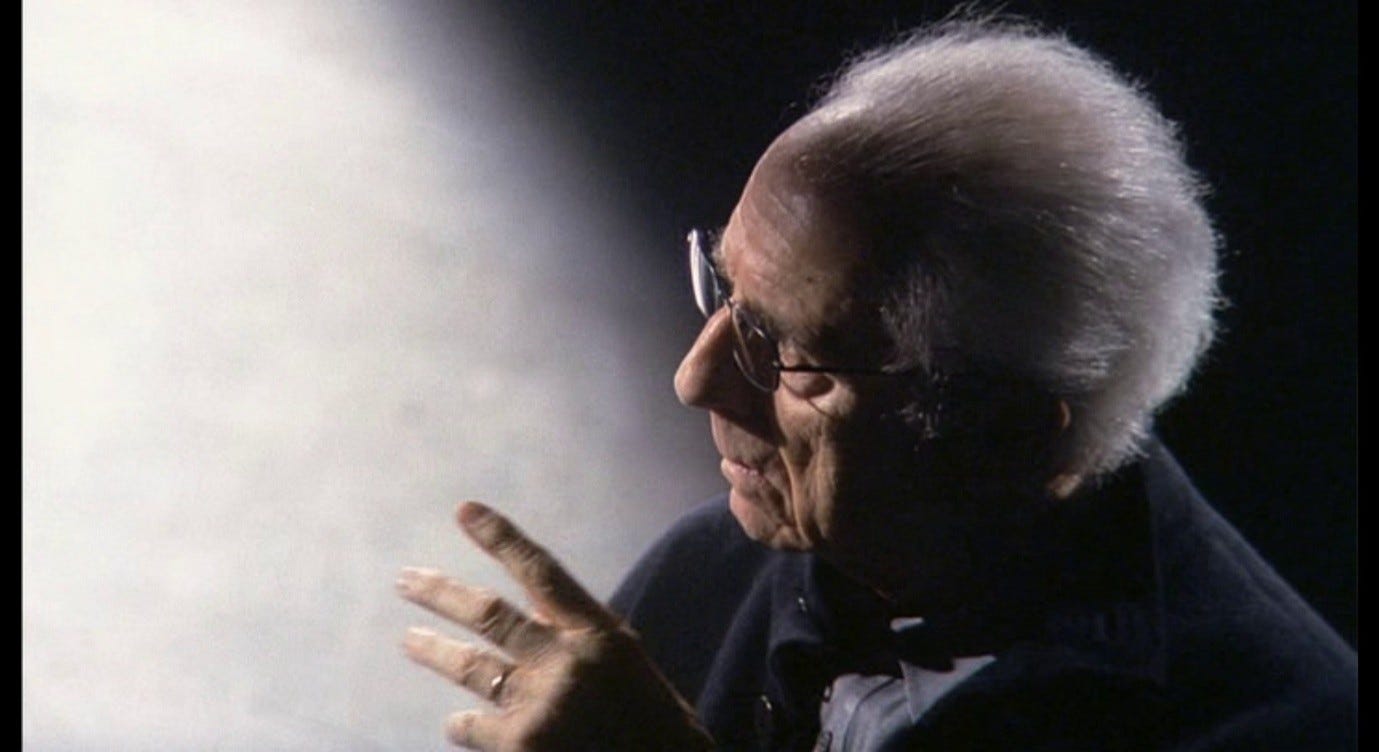

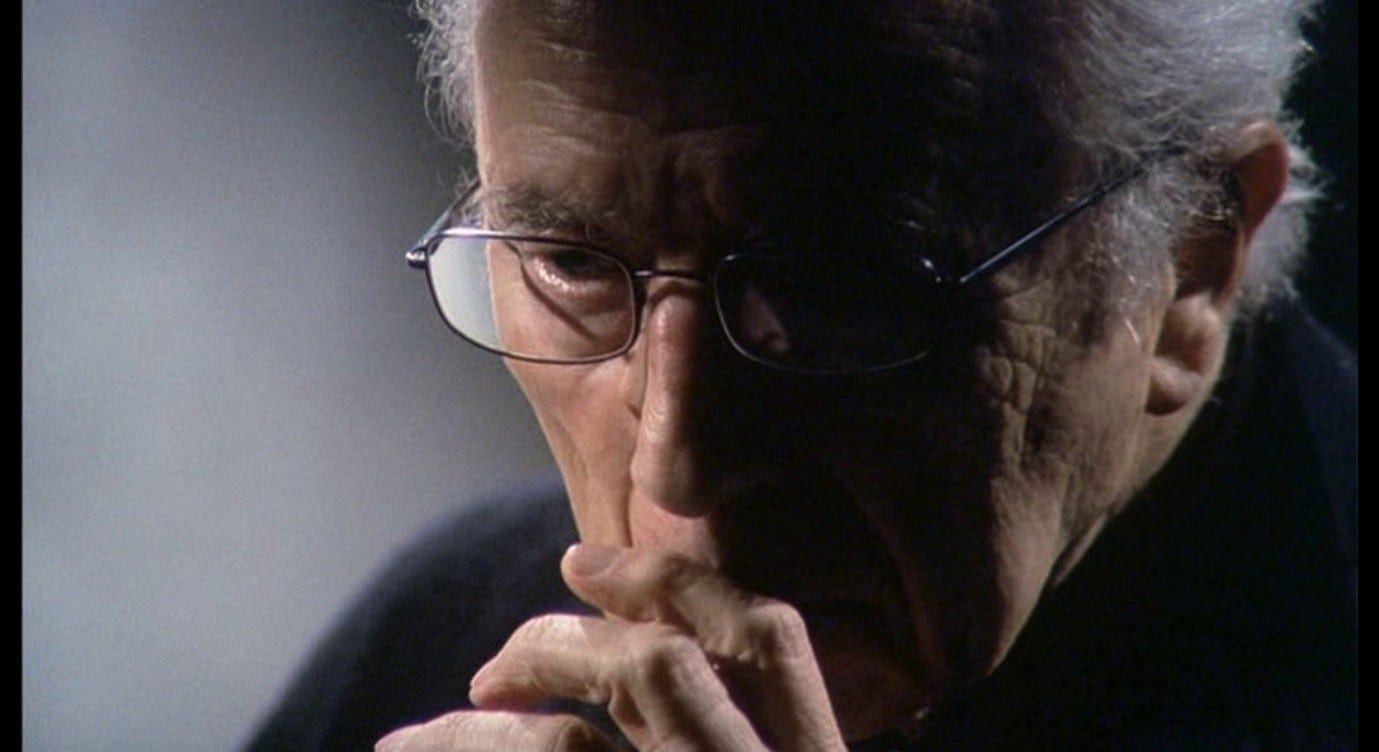

The title of Antonioni’s penultimate film, Lo sguardo di Michelangelo (The Gaze of Michelangelo), ostensibly holds up the artist’s gaze as something extraordinary. The film looks at Antonioni looking, and at what he is looking at, for 17 minutes, as though this look possessed some remarkable power that might be captured, conveyed on film, and communicated to an audience. The film seems to say, ‘Behold the amazing eyes of this great visual artist, the Michelangelo of his day.’ But as we look at this film that looks at Antonioni looking at Michelangelo Buonarroti’s sculptures, the most striking thing is how compromised all of these ‘sguardi’ are.

Laura Rascaroli captures the ambiguity of how Antonioni portrays himself in this film:

The frailty, thinness and quasi-transparency of his body are highlighted […] [It is] an ethereal, fashioned filmic body, a play of shadows and light projected on a screen – as well as an iconic image of a real body, preserved and embalmed by the cinema […] Antonioni’s is a still-flexible and handsome though aged body; stylishly dressed in Armani, he looks confident, smart and blasé, a refined bourgeois intellectual at total ease with himself […] This self-portrait is not, however, […] a sublimated or sanitised version of an old man’s body. The camera does get near to inspect Antonioni’s face in close-up […] to linger on the opaque gaze and the wrinkly skin. […] In Antonioni’s cinema, bodies are always historicised […] This point becomes unmistakably clear through the comparison he mercilessly sets up between his aged, fragile body, connoting a certain type of modern Western masculinity, and the timeless body of the statue, immortalising the Renaissance vision of a heroic, wilful and titanic manliness.8

It may not surprise regular readers of this blog to learn that I see the film in more pessimistic terms. There is something of the confidence and ease that Rascaroli describes in Antonioni’s appearance, but I think the emphasis is far more on this old man’s anxiety and unease, these being the hallmarks of ‘modern Western masculinity’ as Antonioni has tended to portray it. However handsome and well-dressed his male heroes are, they all finish by losing their self-assurance (and sometimes their very existence). In Lo sguardo, I think Antonioni depicts himself as a man who has lost almost everything, both as a ‘looker’ at the world around him and as a creator of artefacts-to-be-looked-at.

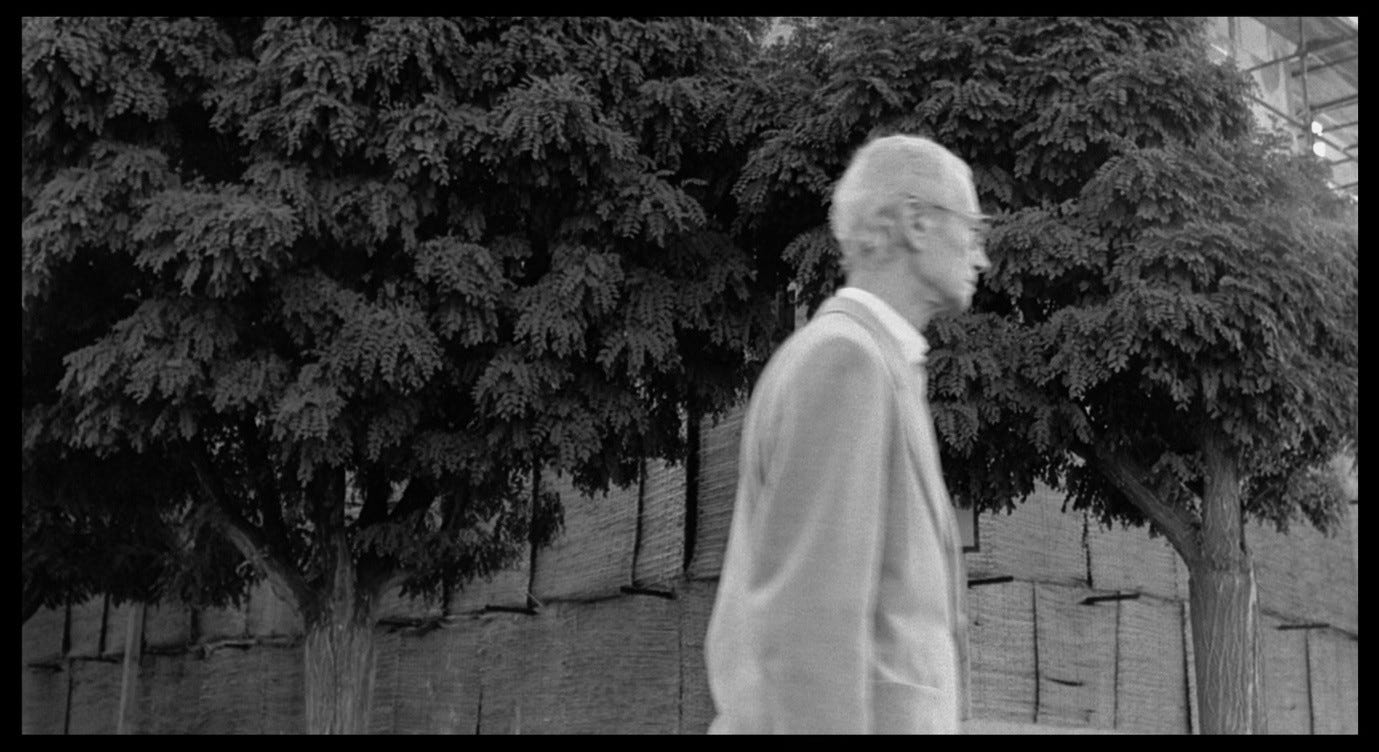

He is visibly near the end of his life, severely debilitated by the stroke he had 20 years earlier, hardly able to move or communicate. When ‘he’ walks through the church, it seems painfully obvious that this mobile figure is not Antonioni. His face is carefully obscured in shadow as it gets closer to the camera, and when we then see Antonioni in close up, we are clearly looking at a different person.

It would be hard for any admirer of Antonioni’s work to watch Lo sguardo without reflecting on how much his powers have been impaired, especially if we are familiar with his other late films (Beyond the Clouds and ‘The Dangerous Thread of Things’), the mixed critical reception they received, or the stories about how challenging they were to make.

In this context, the title Lo sguardo di Michelangelo prompts us to ask what constitutes the ‘sguardo’, what its power consists in, and whether it really amounts to anything significant. The camera looks at the statues, then looks more closely at them and roams across their surfaces, as though trying to see them as Antonioni does, or to capture his efforts to see something in them. We may remember the ending of L’eclisse, in which the camera looked at a grey-haired man in extreme close-up (one segment of his face, then another), then a little less closely (his full face), then less closely still (his body from the waist up), and we were none the wiser about him by the time he strolled off. Who was he, why were we staring at him, and what was he staring at so intensely?

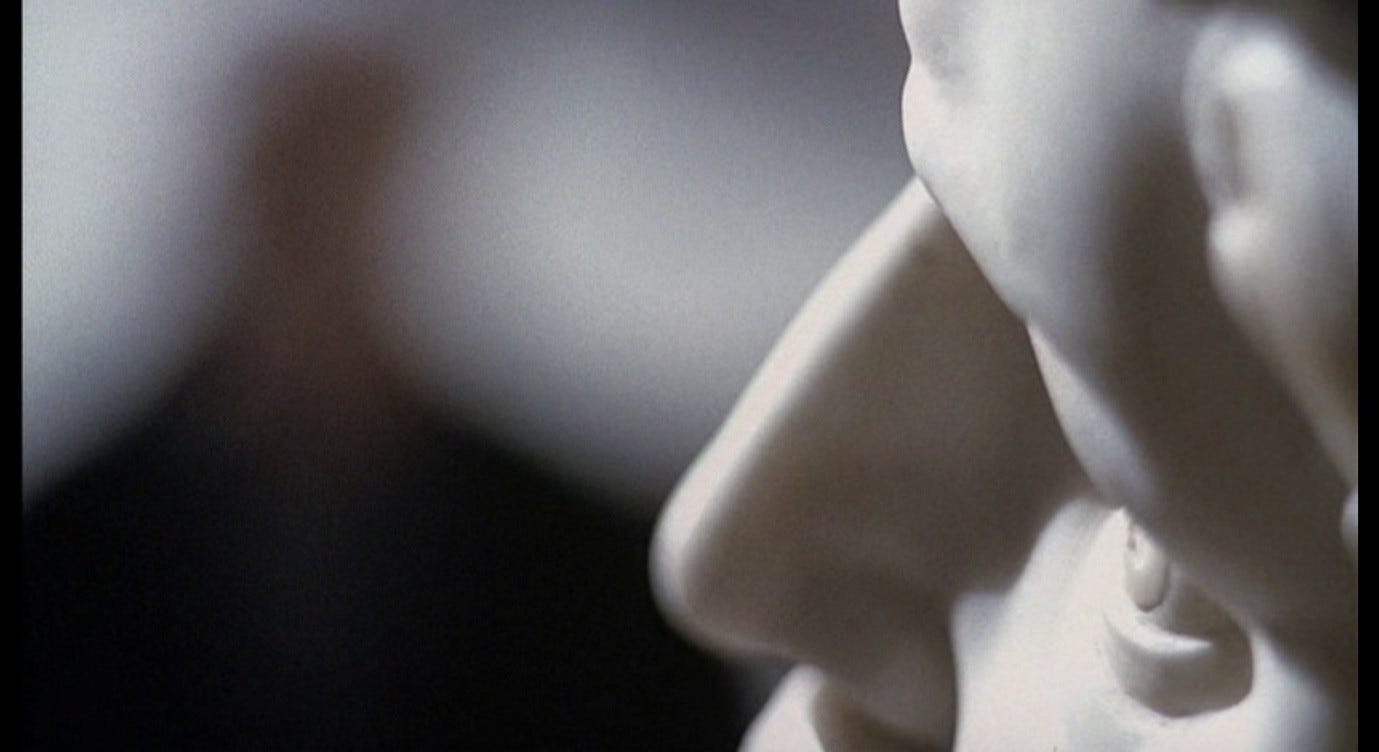

The camera now does the same thing with Buonarroti’s Moses, looking from his eyes to the folds of his cloak to the folds of his beard and back to his eyes again, cutting to a view from the same angle but further away, or closer up.

Rascaroli cites the famous anecdote about Michelangelo striking the statue’s knee and saying, ‘Now speak!’:

Through a series of close-ups and detail shots, articulated through a montage that constantly varies the angle of vision, Antonioni seems to ask Moses to ‘now look’.9

In this reading, the camera does for Moses what it did for the stone lions in Battleship Potemkin, making them seem to awaken and move – or in this case look – through the magic of editing.

But I see something else in Antonioni’s montage: Moses’ eyes are looked at too closely, and are too obviously (however brilliantly) carved from stone. Rascaroli describes Antonioni’s aged eyes as ‘opaque’; the English title of Lo sguardo is Michelangelo Eye to Eye, and of course it is not Buonarroti’s eye that meets Antonioni’s, but the opaque and lifeless eye of the dead Michelangelo’s masterpiece. This, perhaps, is why Antonioni’s camera’s eye keeps returning to the figure above Moses, the reclining sculpture of Pope Julius II. This sculpture, long thought to be the work of Tommaso Boscoli, was revealed as Michelangelo’s in 1999 after being cleaned and inspected more closely. As Christoph Frommel said at the time:

The face shows the very intense interior meditation of someone awakening to paradise. The face and hands look absolutely like Michelangelo. The clothing is unfinished but it looks like Michelangelo too.10 [my emphasis]

Frommel is credited as a consultant on Lo sguardo. Visiting the tomb five years after this discovery, and with Frommel’s words in mind, Antonioni may have wondered what it means to ‘look (absolutely) like Michelangelo.’ Julius’ eyes, unlike Moses’, are closed: this is what Frommel means by ‘intense interior meditation.’ For him, and (he argues) for Buonarroti, these closed eyes and the sleep connoted by them and the pope’s recumbent posture are supposed, paradoxically, to convey a form of ‘awakening’ – this man’s tomb, his resting place, speaks of his resurrection in heaven. But it would be just like Antonioni to look at those closed eyes (overlooked for hundreds of years in the belief that they were the work of a lesser artist) and engage in his own less sublime form of interior meditation. What is the sguardo, after all – whether that of Michelangelo A. or Michelangelo B. – but a blindness to the world outside one’s own mind and a window that no one else can see through, the soul trapped and howling behind it? After looking at Julius’ closed, dead eyes, what do we see in Moses’ open but equally dead eyes? After looking at Moses we look back at Julius again, like a tourist who cannot help returning to the ‘lesser’ work of art because it resonates with us more than the celebrated masterpiece. Do we see a kind of revelation in the pope’s closed, inaccessible face that we fail to see in Moses’ deceptively life-like expression?

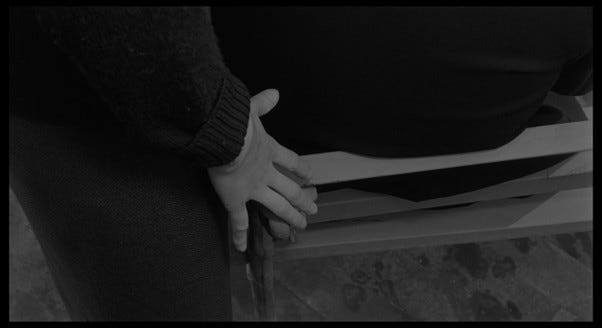

Antonioni’s hand touches the sculpted stone, but hesitantly, only daring to make contact with the edges of Moses’ cloak, the hand hovering in slow motion over the folds.

We remember how Claudia touched Sandro’s hair at the end of L’avventura, or how Giuliana touched Valerio’s in Red Desert – wanting a connection, wanting to understand, but not necessarily (not even probably) succeeding.

What, ultimately, do we see in Antonioni’s face in Lo sguardo? He is still fascinated by the world, still looking at it as he did throughout his career, still possessed of at least some of the insight that enabled him to show us such incredible images. But as well as looking curious, he also looks sad and frustrated, all too aware that his eyes and his creative faculties are not what they were. He is framed looking through the crook of Moses’ elbow, not (I think) at the sculpture itself but at the camera lens, at us, as if to say that all he can show us now is his diminished self and the diminished scope of his sguardo.

‘Niente,’ he would say on the set of Beyond the Clouds, mostly deprived of speech but still trying to convey his displeasure at the way a shot had turned out.11 ‘This is nothing.’ ‘No one really knows what goes through his mind,’ says Wim Wenders, unsure whether the day’s work has pleased Antonioni.12

[W]hen we ask him what the matter is, he crosses himself several times and says ‘Morto’, to indicate his approaching end. He’s been doing that for a long time, Enrica reassures us, and the effect of his saying it was anything but morbid – on the contrary, it was cathartic and kept him going.13

In Lo sguardo, Antonioni looks up at these great works by a long-dead artist, housed in the funereal darkness of the church of Saint Peter in Chains (where, in this film, the lighting prioritises atmosphere over clarity), contemplating his own imminent demise and obsolescence. This, Rascaroli points out, is a common function of the self-portrait, which typically ‘freezes a moment in time, hence capturing the work of death; and each is, potentially, the last one; and, therefore, a memento mori.’14 Like Tanino in Red Desert, Antonioni mostly keeps his mouth closed, though there are moments when he seems about to open it, to express something.

But like Tanino, in that moment of ‘secret and reciprocal creative satisfaction’ that Flavio Niccolini observed 40 years earlier, Antonioni gives us one last fright by refusing to grant us the connection we were hoping for. ‘What do you want of me?’ he seems to say. ‘Niente to see here.’ The film’s title promises us a revelatory vision, but the ‘gaze’ in question is as self-contained and impenetrable as a stone. As in Red Desert, the revelation of truth is a tragic one, not just about the inescapability of death, but about how inescapably separate, silent, and alone we all are.

In short, Antonioni’s titles often make promises in order to frustrate them. These titles refer to things that the characters are striving towards but that are subverted and treated with irony in the film itself, and that may ultimately prove to be unfeasible, unsustainable, or otherwise futile. The title Celeste e verde would have had a similar effect. It refers to Giuliana’s plan to control and optimise the space that she exists in, to give herself sky-blue walls and a grass-green sky – ‘making a world upside-down’, as Murray Pomerance says15 – in which she and the objects around her can co-exist in cool, stable harmony. It also alludes to Antonioni’s comment about the optimisation of industrial spaces to give the workers something to ‘rest their eyes on,’ as though the modern workplace need not be defined by exploitation and drudgery, but might instead become a place of harmonious relations between the workers and the bosses who look after their wellbeing.

Both allusions to the blue-and-green combination – Giuliana’s and Antonioni’s – stand for the idea that colours and other aspects of the environment can be calibrated in order to make people feel and behave in a certain way. And not just people but also objects, as Giuliana says. From the industrial perspective, this means we can turn the sky grey with smog and the earth black with soot, but then restore their original celeste e verde artificially in our new and perfectly calibrated world. From Giuliana’s point of view, it means she can create a refuge from the factories, in an out-of-the-way place such as the Via Alighieri. Angela Dalle Vacche expands on the idea that Giuliana’s imagined celeste e verde world represents a protest against the one that normally confines her:

[T]he ceiling is green and the walls are light blue. Through colour she has inverted the predictable scheme of sky and earth, of mind and body, and thus, thanks to her willingness to experiment, she has distanced herself from that stereotypical association of the ground with the womb, of femininity with nature, which always seems to place her in opposition to the world of science, factories, and cerebral coolness.16

Indeed, Giuliana seeks a form of ‘coolness’ that overlaps with the kind used in industrial settings, but without the oppressively ‘coded’ connotations of those pipes and machines. If, at first glance, she seems anxiously ensconced in a womb-like underground bunker, this impression will be subverted by the grass-green surface above her head and the sky-blue vistas on all sides. It is the grey world outside that is as-if-underground, it is she who is cool and un-disturbed, and the setting she conjures in her shop is not simply a reproduction of the natural order, but a re-ordering of nature with which Giuliana can co-exist harmoniously.

In one interview, Antonioni explains why this quest for harmony is doomed to failure, as part of his larger explanation of his own use of colour in Red Desert:

I wanted to use colour to convey the manifestations of an inner world [un monde intérieur]. It is realistic colour insofar as it communicates the spirit [esprit] of that reality. Each person sees things in a different way. A stain on a wall could be noticed by one person and ignored by another. It’s the same with colour. Each person perceives it according to their state of mind [état d’esprit]. So this neurotic woman buys a shop in which she doesn’t know what to sell. Every day she goes to this street to attend to this shop which she prepares in a totally incoherent, ad-hoc way. She re-paints it incessantly. We see from the paint-pots that all her attention is focused on this effort of painting, but the street she passes through is grey. Even the chestnut-seller’s cart is grey. She travels only in fog [Elle ne traverse qu’un brouillard].17

The verb ‘traverser’ in that last sentence emphasises the idea that Giuliana is crossing from one state into another: in trying to set up this shop, she is attempting to make a passage into another world, as she will do later in her fantasy of the pink beach. But as in that later sequence, the film insists that Giuliana traverses nothing, that however much she tries to create a new world she finds herself only in fog. The Tintal paint has been purchased in great quantities and piled up on the floor of the shop, but the colours of Giuliana’s monde intérieur will manifest themselves in the world around her in spite of all her paint-work. The grey brouillard is always there, defeating the celeste e verde, infecting the sky, streets, fruit, and everything – because, to put it simply, Giuliana’s état d’esprit is one of suicidal depression.

Antonioni’s films often evoke newly created worlds, states of reality that are displaced from ‘the real world’. Commenting on the title sequence of La notte, in which the camera stares into the reflective windows of the Pirelli building from an unseen descending platform, Giuliana Bruno says:

The building is literally ‘scrolled,’ via camera movement that unfolds its visual structure, as an introduction to the film’s psychogeographic journey. The skyscraper’s transparent texture is elucidated as the city becomes reflected in its view. As we travel down the facade, we move from window frame to window frame, as if actually unreeling the twenty-four frames per second that comprise the film strip. The frame of the window thus turns into the filmic frame, with the city imaged within its borders. The building turns into a film.18

Along with the strange electronic music, the effect Bruno describes is what makes the opening of La notte feel confrontational. Yes, those machine-sounds are music and music is nothing but machine-sounds. Yes, this building is a film and a film is nothing but a long line of reflective windows.

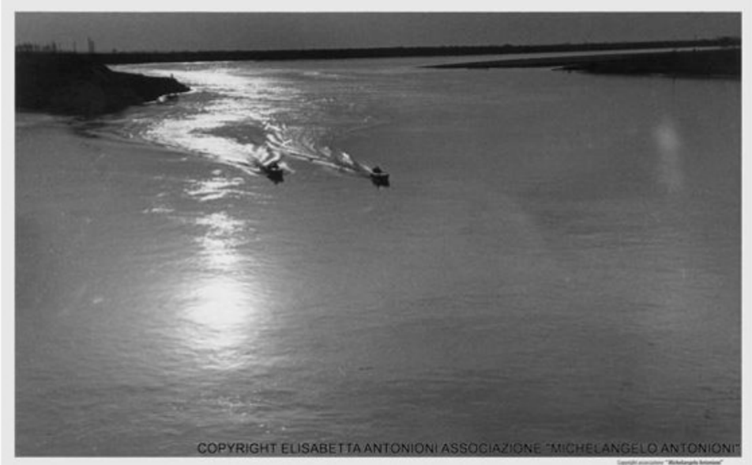

Noa Steimatsky applies a similar principle to two early works by Antonioni: a photo-essay called ‘For a film on the river Po’, and his incomplete documentary on the same topic, Gente del Po. The former includes two still images that are

dominated by large expanses of water that approach the frame in magnitude, effecting an interplay of surface and depth, reflection and opacity: the water surface becomes comparable here to the surface of the photograph itself.19

In Gente del Po, potential storylines seem to be initiated but then are

suspended, time and again […] dissolved in the image of the river itself: in shots of barge movement and the water expanses filling the frame. […] The film’s realist claims […] are repeatedly suspended, like its narrative, in motions of externalization and dissolution, symptoms of a modernist consciousness that identifies the landscape with the space of cinematic representation as such. The gray expanse of the river – ‘flat as asphalt,’ the voice-over observes – that fills the frame repeatedly, opaquely; the graphic division of light and shade on a wall under the opening credits.20

In the earlier photo-essay, Antonioni rejects both the clichés of documentary and the introduction of even a ‘light narrative thread’ which might clash with the ‘poetic discovery’ of the river; any form that ‘dictates precise directions and does not allow for uncertainties’ must be avoided.21 From the start of his career, then, we see his ambition to disturb the audience’s sense of what a film is. The river is the film and the film is the river. In Gente del Po, when a young couple threaten to distract our attention with the prospect of a human-interest narrative,

the camera pans away to the empty expanse of bank, river, opaque sky beyond – suspended landscape elements, signifying nothing in particular, opening, emptying up the little narrative all in the duration of a single shot.22

Steimatsky’s deliberately oxymoronic phrase, ‘emptying up,’ expresses perfectly what these films do in their perverse, drifting movements towards spaces that are, like Joni Mitchell’s cactus tree, ‘full and hollow.’ This surface that signifies nothing in particular is, very particularly, what constitutes the film, what empties up the screen. The emotionally rich (and ‘full’) tableau of the melancholy lovers goes out of focus, is relegated to the bottom-left corner of the frame by the camera-tilt, and seeps out of the film altogether, into the not-film ether.

That camera movement in Gente del Po, panning and tilting up from the young couple to the much fuller emptiness that is the film’s chief interest, is like the movement from Moses to Pope Julius in Lo sguardo, the documentary short at the other end of Antonioni’s career. Those lovers are nothing and Moses’ eyes cannot see anyway. Julius’ closed eyelids turn his sguardo into an empty screen, emptying it up like the Po river, not in an act of salvific meditation but in a negation of the sguardo and of any objects that gaze might focus on. Rascaroli points out a crucial detail in this film:

We both look at Antonioni (there are at least as many shots of him as of the statues) and with Antonioni: several semi-subjective shots, in which the camera is placed just behind Antonioni’s head and frames the side of his face (with his glasses in clear evidence), as well as the field of his vision, invite us to look through his eyes (indeed, quite literally through his spectacles). In these shots, the spectatorial identification with the director is also suggested by the photography: while his image is sharp, his field of vision is out of focus.23

I think there is another – again, more pessimistic – connotation to these over-the-shoulder images. While the film does seem to invite us to look through Antonioni’s eyes, the clarification that it in fact invites us to look through his glasses stresses the difference between these two acts of looking-through. Glasses are meant to bring the object of the wearer’s gaze into focus, but what we see through these glasses is always obscure. At the beginning of one shot, the view through the glasses seems distorted but not out of focus, while the sculpture itself is out of focus; then the focus shifts and the sculpture becomes clear, while the view through the glasses becomes blurred rather than stretched. Then the focus shifts again, and for a split-second we seem to see something clearly through the glasses – but this is soon replaced by darkness as Antonioni’s gaunt silhouetted face dominates the frame.

Do we presume that Antonioni’s gaze is different from ours, that his lens gives focus to what would otherwise seem obscure? Or is that tiny screen, the spectacle-lens, an accurate representation of what and how the great Michelangelo sees: not the crystal-clear human-shaped sculpture perfectly centred in the frame, but a shifting, amorphous, frame-filling mess like the abstract canvases that Giuliana’s gaze presents to her?

Matilde Nardelli argues that the colour-swatches on the walls of Giuliana’s shop ‘function as a self-reflexive enfolding of Antonioni’s own pictorial interventions in the film’s diegesis.’24 In other words, Giuliana is painting her world celeste e verde in the same way that Antonioni has painted the Via Alighieri grey; she is engaged in something like the film-making process. These walls are like the skyscraper windows in La notte and the expanses of water in the (filmed and un-filmed) Po river documentaries: as the camera tilts up to follow Giuliana’s gaze at these walls, we understand that these surfaces are supposed to constitute a new world, a new plane of existence.

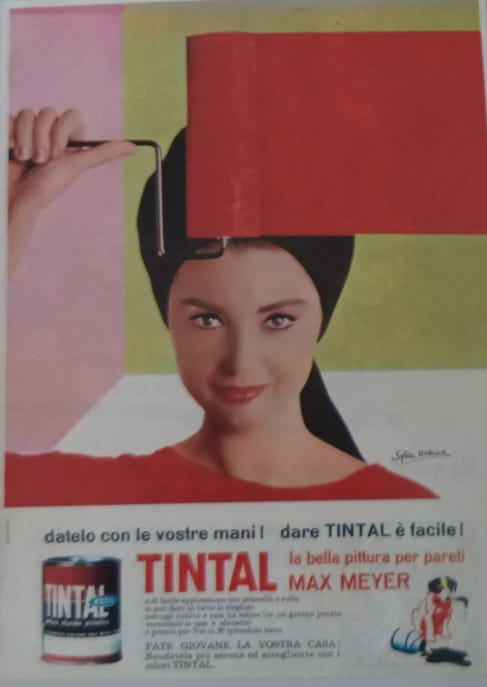

In Red Desert, as Antonioni said, his subject was colour as such, and the working title Celeste e verde would have been a way of saying, ‘This film is the colours Giuliana imagines on the walls of her shop, and those colours she imagines are the film.’ The film was never going to be called Le pareti celesti e il soffitto verde [The sky-blue walls and the green ceiling], not only because this would have been an awful title, but also because the intention was to invoke the colours as such, not the surfaces beneath them. Remember the Tintal advert discussed in Part 2, in which Sylva Koscina paints herself into a box of would-be domestic bliss that consists only of colour, only paint with no solid surfaces on which to apply it.25

That advert deals in concepts: not paint applied to a wall, but colour whose beauty (like the beauty of Sylva Koscina) brings happiness. In a way, this is like Antonioni’s use of colour in Red Desert. We close our eyes to reality, we look through a lens that obscures it, we exist as though in a fog, and there are no walls, no sky, no earth, only the celeste e verde of our monde intérieur. But here we stumble over that most reliable of Antonioni motifs: disappointment. The truth is that Giuliana will never paint these walls, so they will stay as they are – white and desolate – and will form the background to her definitive rejection of Corrado at the end of the film.

Like the forms of love, friendship, freedom, or creative power to which characters aspire in other Antonioni films, and which are inscribed in those films’ titles, the dream represented by the phrase celeste e verde is thoroughly explored and given plenty of space to breathe. It is a mindset adopted by Antonioni himself, insofar as he sought to control and manipulate the colours that appeared in this film. But his sense of what those colours will do is not over-defined, prescriptive, or naively optimistic. Red Desert is both fascinated by and sceptical of the colour-coding ideology embodied in its would-be title.

Giuliana’s primary concern, in choosing the colours in her shop, is for the objects. These objects – whatever they end up being – must not be disturbed. In one of his stories, Antonioni observes a woman who works in a clothing boutique:

[T]hey must have suggested that her demeanor in the shop should be detached and calm, that she should avoid any movement that might distract [disturbare] the customer’s concentration on the objects for sale. The ideal clerk appears to belong to the customary order [ordine consueto] of the things around her, she doesn’t attract to herself the interest intended for those objects. That she attracts mine is normal because it’s an aspect of my profession to observe people in the context of the situations in which they exist.26

The slightly creepy tone of his observations is heightened (though undercut by the tone-deaf musical accompaniment) in the filmed version of this story in Beyond the Clouds, and in both cases it anticipates the ultimately sinister nature of this encounter. Much could be said about the link between the patricidal woman in her shop and Giuliana in hers, but what interests me here is Antonioni’s comment about observing people in context, coupled with his comment about how people adapt themselves to a context, in this case by suppressing aspects of themselves so as not to disrupt the operations of commerce. When Giuliana strives for a similarly non-disturbing context in her shop, this does not seem to be motivated by a desire to sell products, but rather by a very un-commercial concern for the objects themselves. Whereas the clerk has to conform to the ordine consueto of the business they work for, Giuliana is trying to define that ordine consueto in a way that will conform to her needs, which seem tied up with those of the objects. Those objects are to be provided with a comfortable home, not to be sold and got rid of.

In the next sequence of the film, we will learn that Giuliana has trouble differentiating between people and objects. Her desire to create a space in which objects will be kept cool and safe hints at one of the reasons why the industrial landscape terrifies her so much. She lives in a world where everything is product, where things and places are treated as fodder to be burnt, consumed, and subjected to endless transformations. She is drawn to ceramics, an art-form notable for its continuity with the ancient past, with artisanal skills and processes, and with the earthen materials the pots are made from. The clay is shaped, baked, and glazed to become a heat-resistant container, then it is treated as a useful but delicate object to be preserved and handled with care. These are presumably the aspects of ceramics that attract Giuliana, especially since she admits to having no special expertise on this subject.

When Corrado tries to help by observing that Faenza is famous for ceramics, Giuliana seizes on this as a cue to action: she must travel to Faenza. But when she opens her notebook to update her to-do list, she is immediately overwhelmed by the number of phone calls she has to make.

Again, the point is not that Giuliana lacks a proper work-ethic or that she suffers from a neural disorder that prevents her from performing tasks. She will never open this shop because she is not really trying to open a shop. As we have seen, her choice of setting and her fixation on colour-schemes indicate her need for a certain kind of space. There is something about the idea of running a small shop, learning about ceramics in Faenza, and making lists of people to call that speaks to this same need, but the moment she starts to put these ideas into action, it becomes apparent that they will not really help her. We will learn more about Giuliana’s ‘need’ and why it will remain unfulfilled when we see the initiation of her relationship – if we can call it that – with Corrado.

Next: Part 15, The beginning of the affair.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Pavese, Cesare, Among Women Only (1949), trans. D. D. Paige (London: Peter Owen, 1953), p. 87

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘My desert’, trans. Allison Cooper, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 82-83; p. 83

Maurin, François, ‘Red Desert’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 283-286; pp. 283-284

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; p. 294

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 443

Niccolini, Flavio, ‘Diary’ (1964), trans. Maggie Fritz-Morkin, Words Without Borders (02 March, 2011). The original Italian text is published in Michelangelo Antonioni, Il deserto rosso, ed. Carlo di Carlo (Bologna: Capelli, 1964).

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 124

Rascaroli, Laura, The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film (New York: Wallflower Press, 2014), pp. 185-186

Rascaroli, Laura, The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film (New York: Wallflower Press, 2014), p. 183

Willan, Philip, ‘Michelangelo’s lost statue finally dusted off’, The Guardian, 09 April 1999

Wenders, Wim, My Time with Antonioni, trans. Michael Hofmann (London: Faber and Faber, 2000), pp. 43, 50, 58-59, 65

Wenders, Wim, My Time with Antonioni, trans. Michael Hofmann (London: Faber and Faber, 2000), p. 13

Wenders, Wim, My Time with Antonioni, trans. Michael Hofmann (London: Faber and Faber, 2000), p. 24

Rascaroli, Laura, The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film (New York: Wallflower Press, 2014), p. 177

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 92

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 57

Manceaux, Michèle, ‘Dans de Désert rouge’, L’express (16 January 1964), pp. 19-21; pp. 20-21. My translation.

Bruno, Giuliana, Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture and Film (New York: Verso, 2007), p. 98

Steimatsky, Noa, Italian Locations: Reinhabiting the Past in Postwar Cinema (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), p. 12. The two images are taken from Menduni, Enrico, ‘Il fiume Po tra cinema e fotografia: Transiti e ipotesi di lavoro’ (presentation slides), 02 May 2018. Both photos copyright Elisabetta Antonioni, Associazione Michelangelo Antonioni.

Steimatsky, Noa, Italian Locations: Reinhabiting the Past in Postwar Cinema (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), p. 32

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Concerning a Film about the River Po’, in Springtime in Italy: A Reader on Neo-Realism, ed. and trans. David Overbey (Hamden: Archon Books, 1979), pp. 79-82; p. 81. The essay was originally published as ‘Per un film sul fiume Po’ in Cinema 68 (April 1939), pp. 254-257.

Steimatsky, Noa, Italian Locations: Reinhabiting the Past in Postwar Cinema (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), p. 33

Rascaroli, Laura, The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film (New York: Wallflower Press, 2014), p. 184

Nardelli, Matilde, Antonioni and the Aesthetics of Impurity: Remaking the Image in the 1960s (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), p. 33

Image posted by ebay.it seller ‘stems23’, item listed as ‘advertising Advertising 1964 TINTAL MAX MEYER’

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘The girl, the crime…’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 79-86; p. 82. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘La ragazza, il delitto…’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 91-100; p. 94.