This post contains spoilers for This Sporting Life.

‘What do you think I should sell?’ Giuliana asks Corrado. He is bemused: doesn’t she know what she wants to sell in her own shop? ‘Yes,’ she says, ‘I’d like ceramics, but I know nothing about them.’ We might initially assume that Giuliana, aware of her own ignorance in these matters, is asking Corrado what kind of shop would be most commercially viable, what goods would sell best in the current economic climate. But this project is not about developing and proving her business skills, and I think her question is motivated by something different. She wants Corrado to make a suggestion because then the shop will be founded on a relationship – it will be, in part, his idea, and he will be her collaborator.

In Part 14, I noted that Giuliana has a habit of uttering non-sequiturs that force Corrado to ask for clarification. What should be blue? What should not be disturbed? What does she need to write down? This habit might be indicative of Giuliana’s self-absorption: lost in an internal dialogue with herself, she forgets the other person in the room or neglects to give him the information he needs in order to join the conversation. But it is also the opposite of self-absorption: by leaving certain things unsaid Giuliana invites Corrado to ask questions or to fill in the blanks himself, but in any case to show an interest and engage with her. It is a technique often used by screenwriters to create dynamic back-and-forth dialogue between characters; in this case the technique also serves an important character function.

Up until now, we have seen Giuliana making tentative and fruitless attempts at human connection: buying the sandwich from the factory worker, offering to share it with her son, telling Ugo about her nightmare. This scene with Corrado is the first time we see Giuliana enjoying sustained, functional contact with another human being, without being rejected, misunderstood, or (as far as we know) objectified. Twenty minutes into the film, this comes as a relief. Corrado – having gone out of his way to seek her out – seems like a potential source of redemption, someone who is finally engaging with Giuliana on her terms. Upon arriving in the Via Pietro Alighieri, he pokes his head into the door of Giuliana’s shop, then quickly retreats and waits for her in the street. She tentatively comes outside and asks if he was looking for her.

Corrado’s hesitancy and awkwardness resemble Giuliana’s (for instance, when she sought out Ugo in the factory), but he is also trying to respect her boundaries. He does not want to begin by intruding on the space of her shop; the camera itself refuses to give us a reverse-shot of what Corrado sees inside, as though sharing his respect for this private area. We are not allowed to see it until Giuliana leads him in.

Corrado does not ignore Giuliana when she says strange things, but instead asks follow-up questions. When there is a misunderstanding between them, they laugh about it rather than simply becoming embarrassed and distant. Ugo does not engage in dialogue like this. For him, the non-sequiturs would be symptoms of Giuliana’s failure to ‘ingranare’ – her gears do not mesh – but Corrado seems more accepting of them, and indeed seems to ‘mesh’ with them himself. When he speaks for any length of time during this scene, Corrado almost always ends up correcting or contradicting himself. He lies about having seen her go into the shop, then retracts the lie. He says that Ugo did not tell him anything about her, then lists several things Ugo told him – and his hesitation makes it clear that he is still holding something back. When Giuliana asks where he lives, his answer is comically convoluted, and he ends up concluding that he has no fixed sense of origin, belonging, or direction:

GIULIANA: And you, what do you do?

CORRADO: How do you mean, what do I do?

GIULIANA: Yes, where do you live [dove sta]? In Bologna?

CORRADO: No, I live in Milan. Actually I’m from Trieste – I was born there. When I was little my parents were transferred to Bologna, then they were sent to Milan, then I went back to Bologna several years ago. But I have to leave again [Ma devo andarmene anche di lí, literally ‘But I have to leave even from there’]. It’s a little complicated.

GIULIANA: Why complicated?

CORRADO: The truth is that I… I don’t like [Non mi va] to stay in one place any more than another. And so I’ve decided to leave.

For Giuliana, setting up this shop in this place is symptomatic of her own sense of displacement and desire for displacement from the world she usually inhabits. When she asks Corrado, ‘Dove sta?’, it turns out he suffers from a similar sense of and desire for displacement. He could just say, ‘Yes, I live in Bologna,’ but because of his complex childhood he instead has to explain why he both does and does not live in Milan. He has none of the confidence of Verushka in Blow-Up: when the photographer says to her, ‘I thought you were supposed to be in Paris,’ she replies, ‘I am in Paris.’ For both characters, where they ‘are’ is a state of mind, but for Corrado it is more a question of where he isn’t. His approach to initiating the relationship with Giuliana is also largely negative: he does not enter her shop, he says he does not want to start with a lie, he cannot tell her what he is doing or where he lives.

When Giuliana asks where Corrado is going next, she immediately starts to leave the shop before he has time to respond, as though she takes it for granted that there is no real answer to that question. It is like the nephew’s question left hanging at the end of Identification of a Woman – ‘And then?’ – in that it has more weight and significance when left unanswered. Just as it does not matter what Giuliana is planning to sell in her shop, so it does not matter where Corrado is going. He never goes anywhere, he only leaves. At the end of this scene, each character assumes they are following the other; neither of them has a destination. There is a real sense of release when Giuliana laughs about this. It feels like there is an immediate shared understanding between these two, reflected in the mode and content of their confused dialogues.

Clearly, Giuliana wants to confide in this new friend, but for now she is hesitant. When Corrado says he does not want to ‘start with a lie,’ she asks what he means: what are they starting? This is not a rebuff (along the lines of ‘What is that supposed to mean?’), but a sincere question about the nature of their relationship. She is struck by the implication that their connection will continue to develop after this first encounter, that this will be ‘something’, and she wants to know what kind of ‘thing’ it will be. When she asks Corrado what Ugo has said about her, she is testing the water to see whether they can discuss her accident and whether this man is trustworthy. After the encounter with the fruit-seller, when Corrado asks (for a second time) whether she is tired, Giuliana says, ‘I’m always tired.’ She is beginning to confide in him about her condition, but then she checks herself, pats her hair down, and says, sensibly, ‘No, not always. Sometimes.’

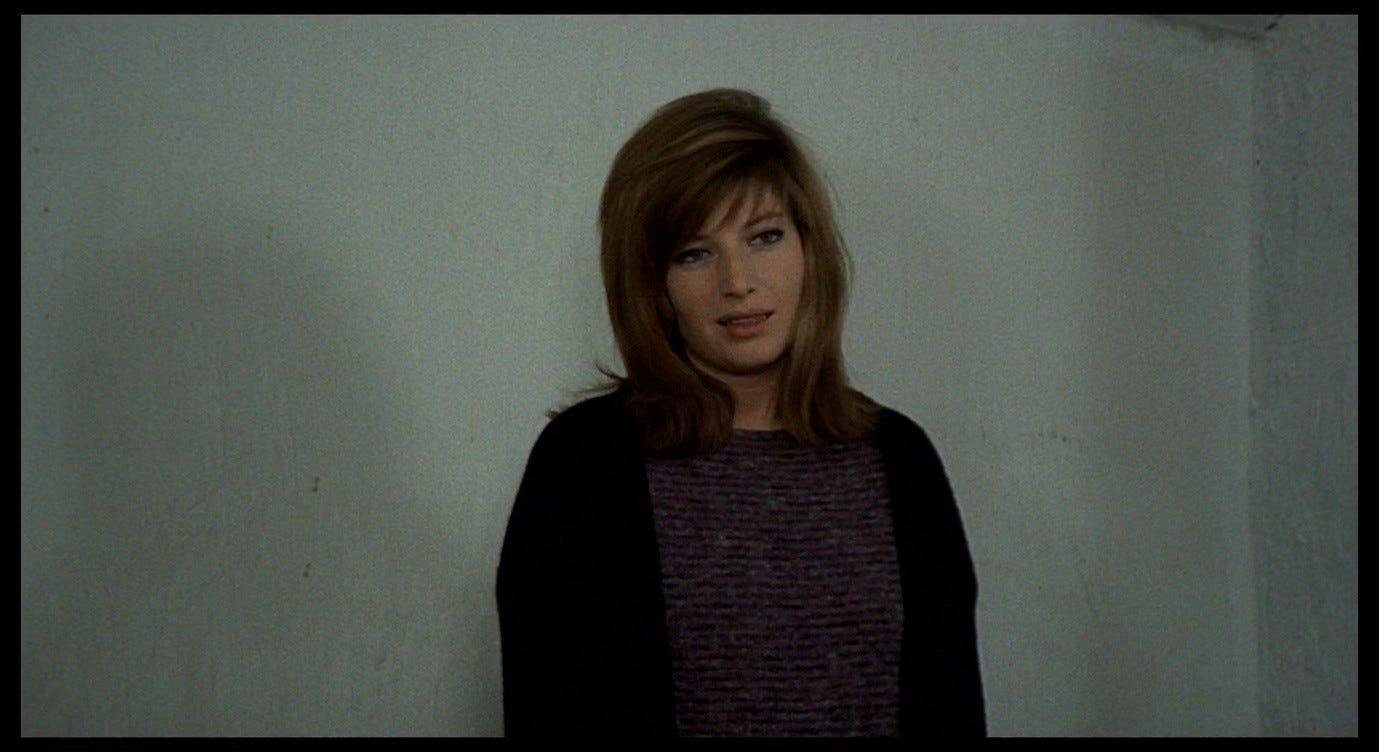

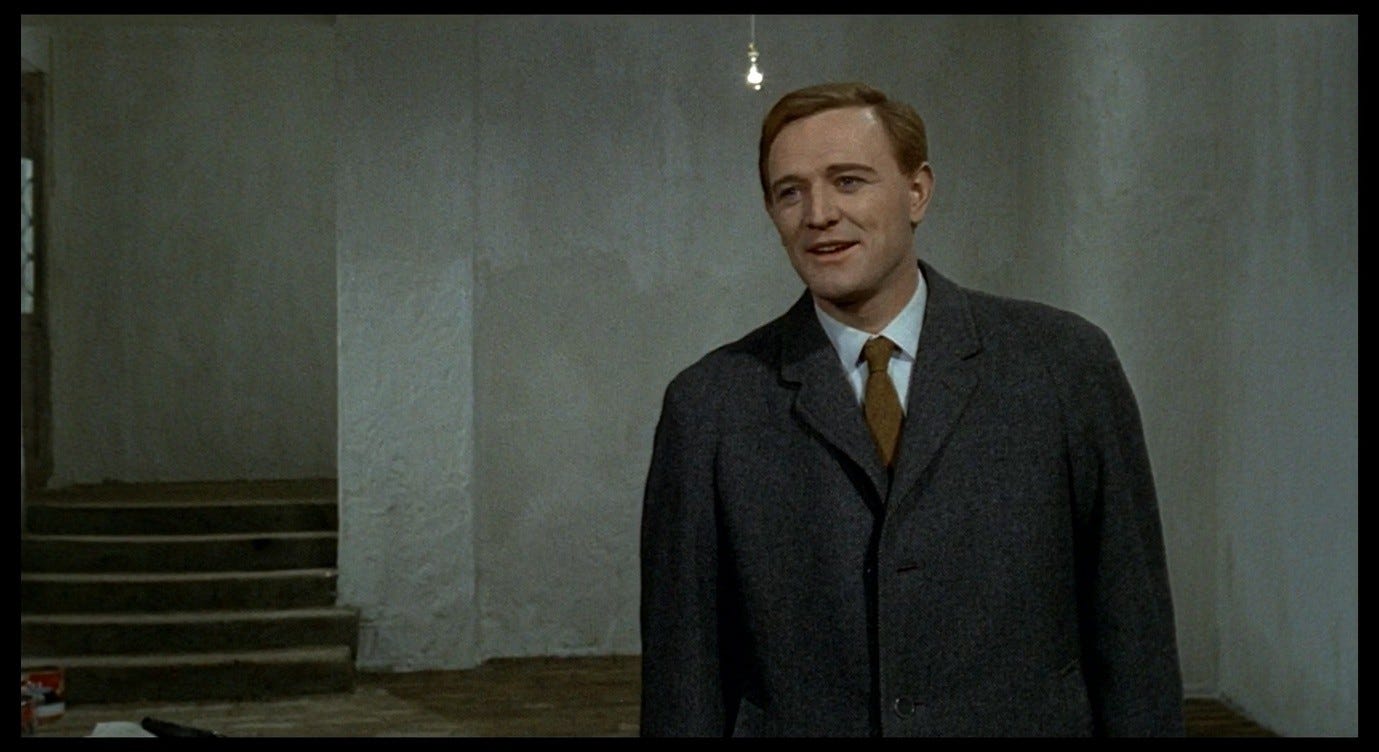

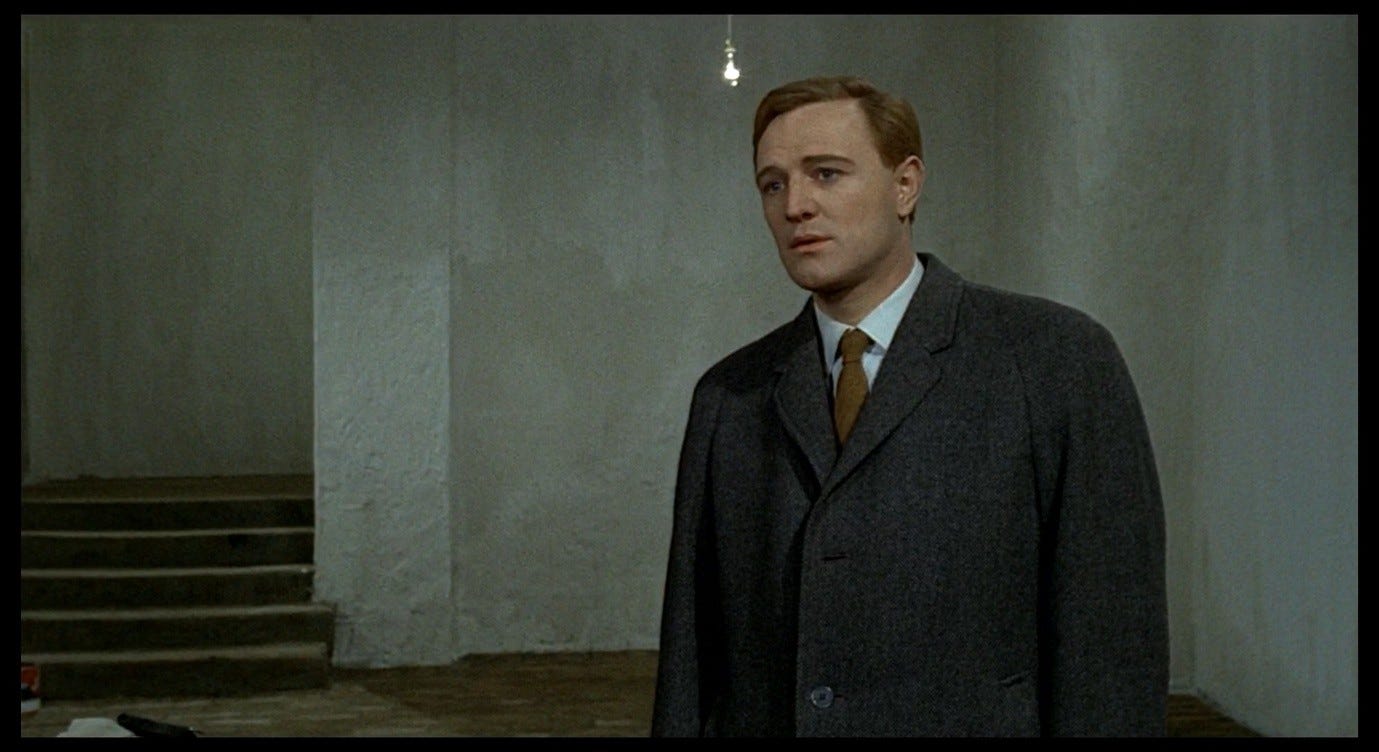

Monica Vitti performs such moments with a masterful control over her facial and bodily gestures. They convey, in great detail, Giuliana’s barely contained emotional torment and her fitful attempts to appear composed. Richard Harris, on the other hand, is clearly being directed to use almost no gestures, like a man who is barely able not to contain his emotions. From his first appearance in this scene, when he gets out of his car, Corrado wears an inscrutable expression on his face.

He often seems to be frowning as though looking for something or pondering what to make of something, then his face goes blank again. His performance reminds me of the joke about Richard Gere only having two facial expressions: ‘Where did I park my car?’ and ‘So that’s where I parked my car.’ Corrado smiles and even laughs from time to time, but only slightly. For the most part, his face is all emptiness; at any given moment, we could read boredom, sympathy, or contempt into it.

This is a fascinating way to make use of Harris’s talents following his breakthrough performance in This Sporting Life the previous year. Michael Feeney Callan, in his biography of Harris, describes how he came to be cast in Red Desert:

Antonioni, Italy’s most daring director, was […] writing fan letters and courting him on the long-distance telephone. Antonioni loved This Sporting Life and begged Harris, ‘Come walk the backstreets of Roma and find inspiration with me.’ […] Most engaging of all was Antonioni’s description of the character Corrado Zeller, the lover-catalyst in the life of Vitti’s Giuliana, whom Harris would play. ‘He was a moral wreck, and I identified with that.’1

That Antonioni loved This Sporting Life is both unsurprising – it is a bleak, beautiful film about loneliness – and something of a shock after seeing Harris’s dead-in-the-water performance in Red Desert. Why wouldn’t Antonioni want Harris to emote as he had done in the earlier film? His male leads immediately before and after this – Alain Delon and David Hemmings – are inarticulate ‘moral wrecks’, no doubt, but they are allowed to be dynamic and expressive, to the point of being flamboyantly silly or melodramatic at times. So why direct this notorious hellraiser, Richard Harris, to perform as though he were under heavy sedation?

The protagonist of This Sporting Life, Frank Machin, is perhaps the least articulate and least accessible protagonist to appear in the ‘angry young men’ films of the early 1960s. Frank’s unchecked aggression and grand-standing are ways of displacing emotions rather than expressing them, and his ‘real’ feelings – his inner life – remain opaque for much of the film. Penelope Gilliatt’s contemporary review praised Harris for evoking an ‘agonising tension between a rich instinctive life and a poverty-stricken expressive life,’ and concluded that ‘Like the classical tragic hero, Frank has no power to change his life because he has no insight into it; all he has is a final stab of knowledge about how he looks to other people.’2

Richard Harris has a very distinctive mouth, which This Sporting Life draws attention to through a framing narrative (spanning the first half of the film) in which the character’s front teeth are broken during a rugby game.

When he is not nursing his smashed, bleeding mouth, Frank is often chewing gum. His jutting lips pout when they are closed and seem poised to attack when they are open. They can be defiant, confrontational, stubborn, or defensive depending on how Harris positions his head or his eyes. Frank is a seething mass of emotion, desperate to express himself but also terrified of doing so, and ultimately, perhaps, incapable of doing so. If you get close to him, you are likely to be hurt or even destroyed.

With Corrado Zeller, much of this is stripped away. It is hard to imagine him experiencing – let alone externalising – any of Frank Machin’s passionate, agonised frenzies. Whereas in This Sporting Life Harris worked hard to give the impression of intense feelings just beneath the surface and tragically unable to manifest except through violence, in Red Desert he gives the impression of sheer emotional hollowness. When talking to Ugo in the factory courtyard, Corrado complained mildly about having to follow in his father’s footsteps, meaning that he is not working in his preferred field of engineering. Now, with Giuliana, he comments with equally mild chagrin on his lack of place and lack of direction. His mouth gestures are similar to Frank Machin’s, but now the jutting lips seem to pout philosophically, resignedly, or just plain stupidly, hanging open with indecision rather than aggression. Frank deployed his body like a high-powered weapon but Corrado can barely walk across the room. When called upon to explain where he lives, he puts his foot up on a chair as though bracing himself, as though he needs to rest one leg so that a modicum of energy can be channelled to his head while he gives his incoherent little speech about Trieste, Bologna, and Milan.

However, there is a crucial similarity between Frank Machin and Corrado Zeller. This Sporting Life is haunted by two questions about Frank. The first is: what does he really feel? The film examines its protagonist with an inexhaustible curiosity, but it does so in a way that leaves the exact nature of his inner life just beyond our grasp. The second question is concerned with the relationship at the heart of the film, between Frank and Margaret. For a while the question seems to be: will Frank help Margaret or hurt her? She is still reeling from the death (by probable suicide) of her husband, and she is unhappy to a degree that may qualify as clinical depression. We are left uncertain whether Frank is just what she needs or whether he poses a threat to her already fragile state. But towards the end of the film, it becomes clear that the real question is: how much will Frank hurt Margaret? These questions hinge on the issue of Frank’s repression. Because we cannot access his inner life, we also cannot tell how it will impact those around him when it finally erupts.

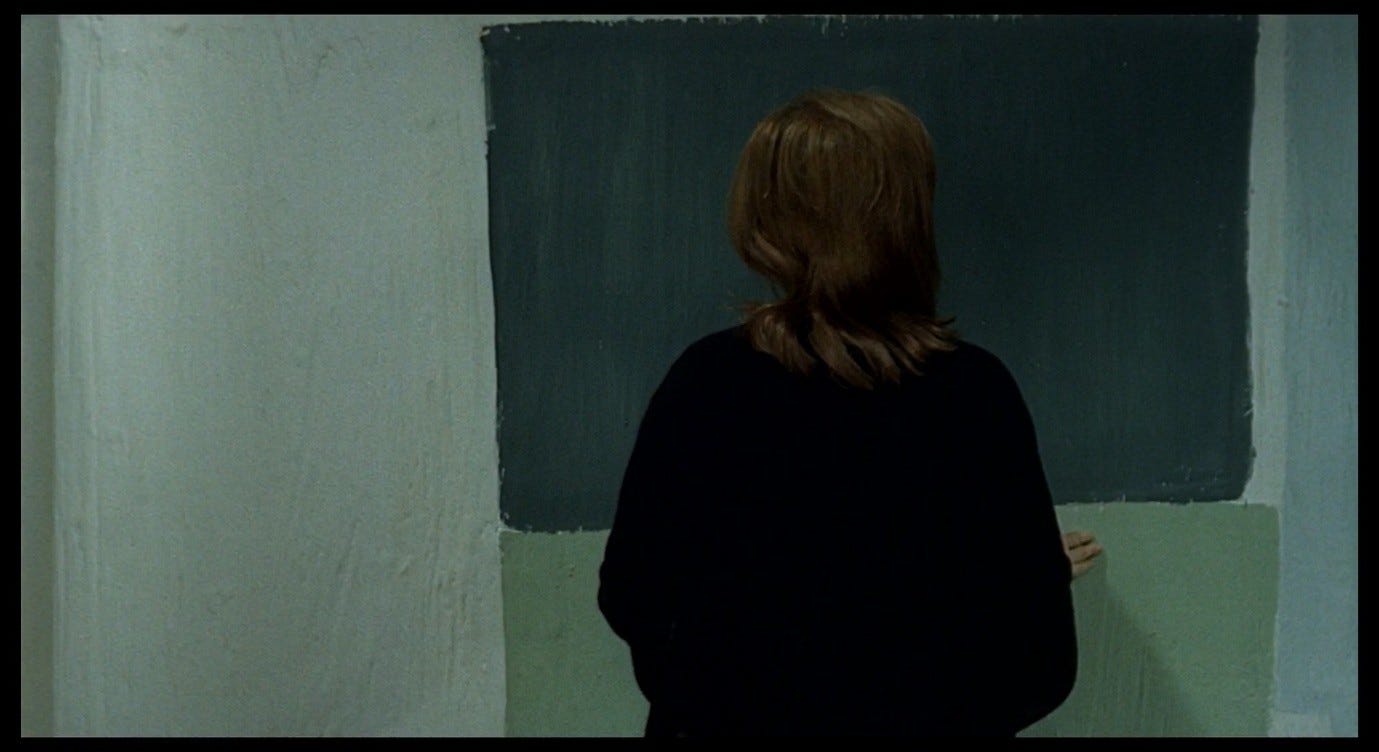

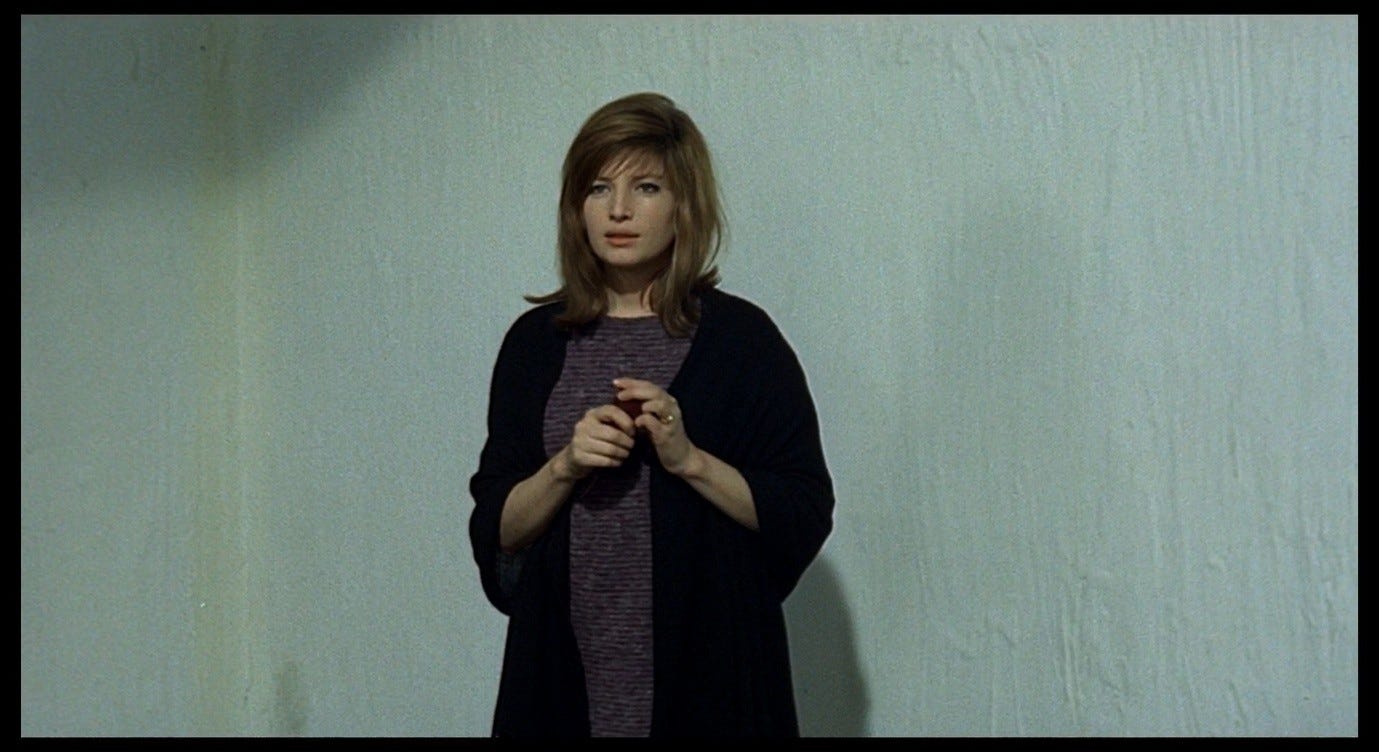

In Red Desert, these same questions apply to Corrado and his relationship with Giuliana. His opacity makes us wonder about his emotions and motivations. At the same time as we sense a connection between these two people, we feel vaguely anxious about the nature of that connection. Just before Corrado’s foot-on-the-chair speech, Giuliana touches the paint on the wall and rubs her finger.

We have seen what is at stake for her in the celeste e verde fantasy: these colours are part of her attempt to create an inhabitable space for herself, a safe environment where she can live without overheating and burning up. We see her standing against these colour-blocks, testing them out to see whether they have ‘taken’, whether this place could be what she needs it to be. The colours on the wall form a kind of rough spectrum which we see her travelling along on her way towards Corrado. Her colour trials are linked to her ‘trial’ of him. Is he good for her? Will she be safe with him?

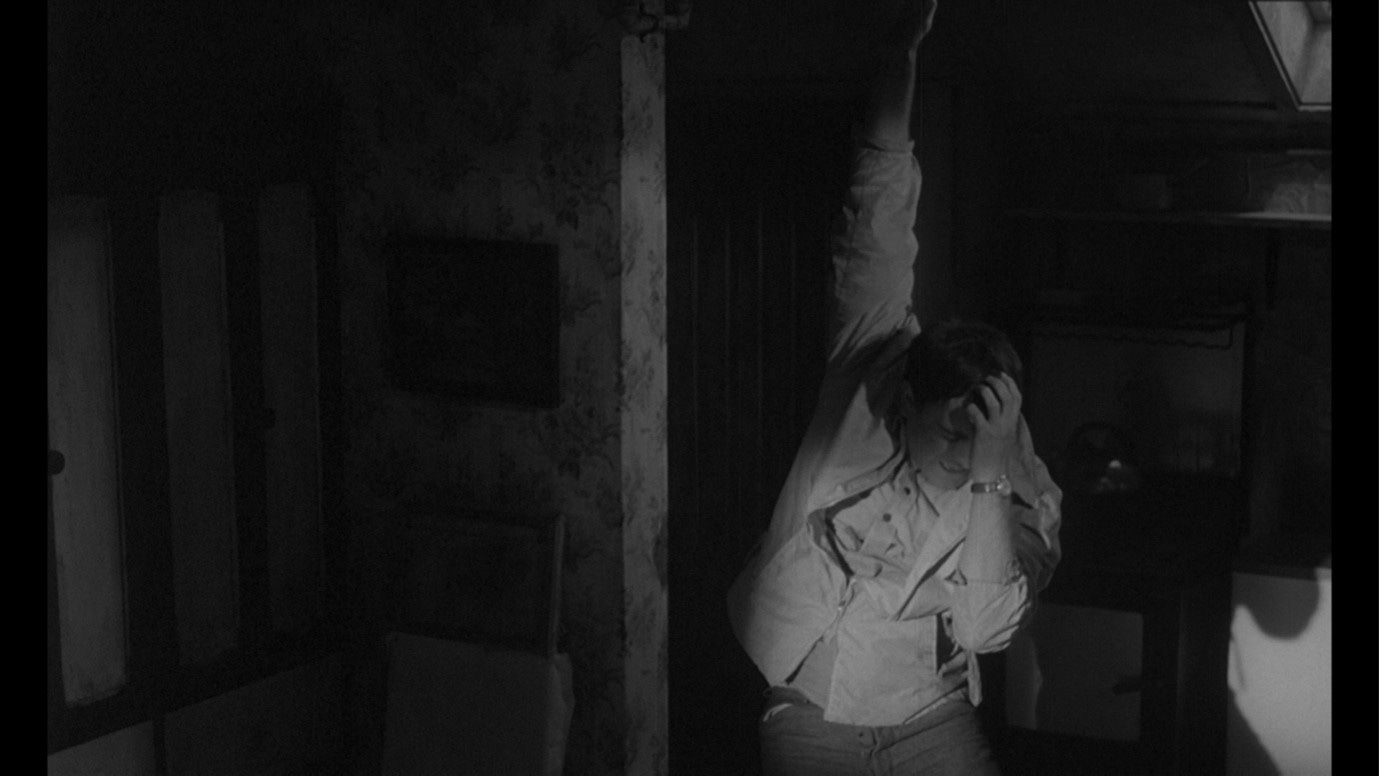

Margaret in This Sporting Life always seems to know that Frank is bad news, resulting in a horrible sense of claustrophobia as he forces himself more and more intrusively into her home and her mind. We spend so much time in the shadowy, grimy kitchen that it becomes imbued with the characters’ emotions, darkened and re-shaped by the conflict between them.

Roberto Gerhard’s disturbing, dissonant score is reminiscent of contemporary scores by Zdeněk Liška and Jerry Goldsmith, often conveying a level of menace that seems disproportionate to what is on screen, until it is validated by the denouement. ‘You want to kill me!’ screams Margaret when Frank confronts her with her husband’s suicide and blames her for it.

He has poisoned not only her home and her past marriage, but even her mind: soon after this, Margaret is hospitalised with a brain haemorrhage, which her neighbour initially calls ‘An attack – some sort of attack.’ Frank is like the spider that crawls above Margaret’s hospital bed just before blood comes pouring out of her mouth, indicating her death.

‘I can love, can’t I? I can, can’t I?’ Frank begged his friend in an earlier scene, confessing his fears about his relationship with Margaret.

The film’s nihilistic conclusion seems to be that he cannot, that his ‘kind of loving’ is a kind of attack. Something in Frank’s background has shaped him to be incapable of relating to others except by crushing them.

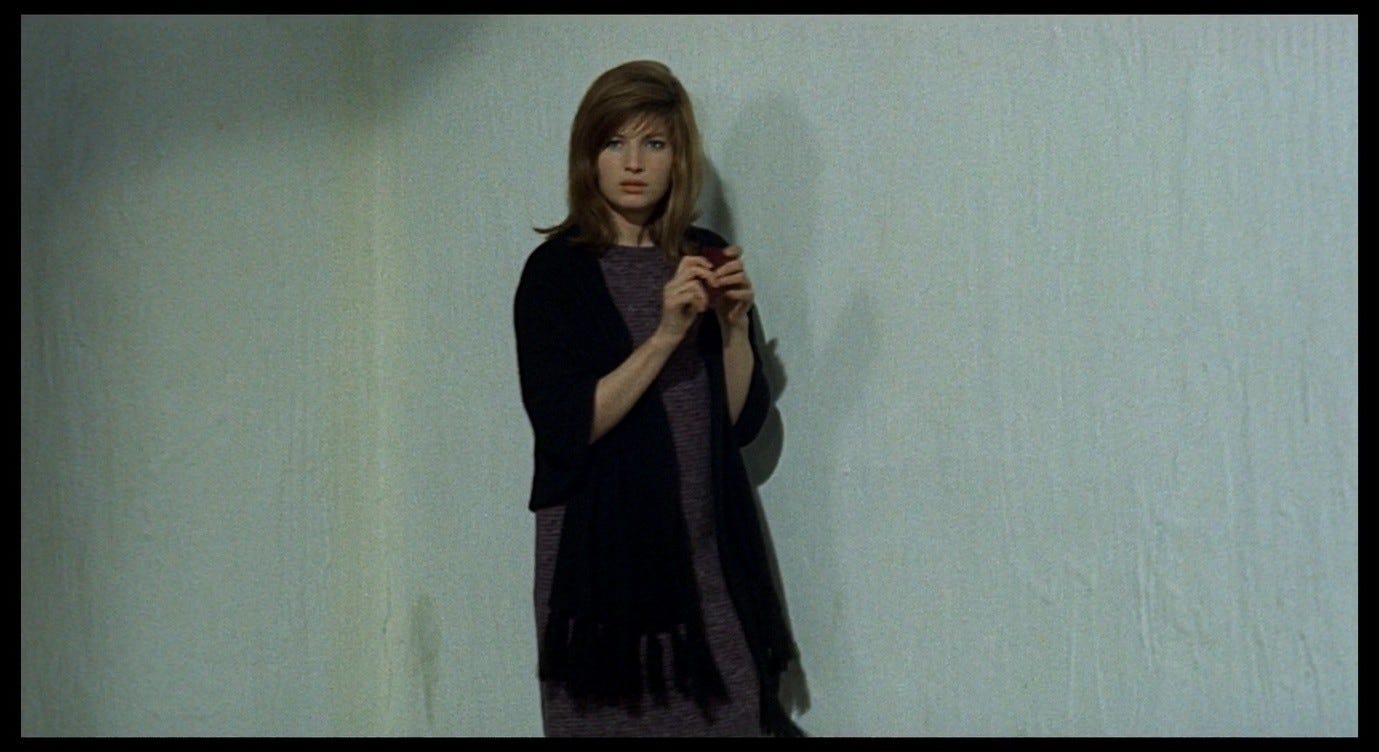

Corrado may seem to have been shaped by his background in a way that would enable him to relate well to Giuliana. When he gives his rambling account of moving from one city to another, the camera cuts back to Giuliana looking searchingly at him.

At one point, we see her head from behind (and out of focus) passing in front of the camera, obscuring Corrado for a moment.

She is moving across the room, regarding this new friend from different angles, attending closely to what he says and does, trying to see him as clearly as possible. He answers the question, ‘Dove sta?’, by saying that he lives in many places and none, while Giuliana’s gaze situates him in many different positions within the room, testing out different answers to the question, ‘Where is Corrado?’ just as she is testing out different colours in different parts of the walls and ceiling. How, and from what perspective, can she relate to this man?

Margaret almost always looks at Frank with undisguised hostility: when you know how This Sporting Life ends, it is as though she were looking at a wild animal that she is too tired to run away from, torn between resisting her fate and resigning herself to it.

In Red Desert, Giuliana’s look is full of trepidation but genuinely open and enquiring. For all Frank’s inarticulacy, it is obvious what he is; with Corrado, it is only obvious what he isn’t, making him like those desert spaces that Antonioni characters are so often drawn to, open and inviting and full of vague possibilities.

Frank Machin turns out to be filled with a dangerous rage that is all the more dangerous because it has been so heavily repressed. Corrado Zeller turns out to be dangerously empty, and his emptiness is all the more dangerous because it remains hidden for so long. Richard Harris was miserable on the set of Red Desert, partly because Antonioni refused to discuss motivations – either Corrado’s or his own – and presumably because this refusal was indicative of the character’s essential hollowness. The result is a performance that continually searches for something to express but never finds it; as such, I think it is a perfect piece of acting. Harris said of Antonioni, in between more critical comments:

He’s a marvellous director. He understands Monica Vitti well, and Monica needs to be sort of wound up like a doll, and then let loose – then she goes through all the emotions of acting, whatever she is told to do.3

While Vitti is asked to express the full gamut of emotions in Red Desert, Harris is asked to do the exact opposite. His performance does not even seem to arrive at that gamut, any more than his character is permitted to ‘be’ in one place or another. Corrado drifts through his own life and other people’s, always on the verge of showing an interest or making a connection, but never quite doing so. He is dangerous because you look at him and think there must be something there. His smile seems kind and tender, his questions seem to show curiosity, his journey to seek out Giuliana seems to mean that he likes her. Little as there is to work with here, it is more than Giuliana tends to get from other people. Her initial trepidation in seizing this lifeline will dissipate as the film goes on. She will open herself up more and more to Corrado, thinking that in him she has found a true friend who will help her. But in the end, this man will turn out to be nothing: he will merely open up a deeper and darker abyss for Giuliana to stare into.

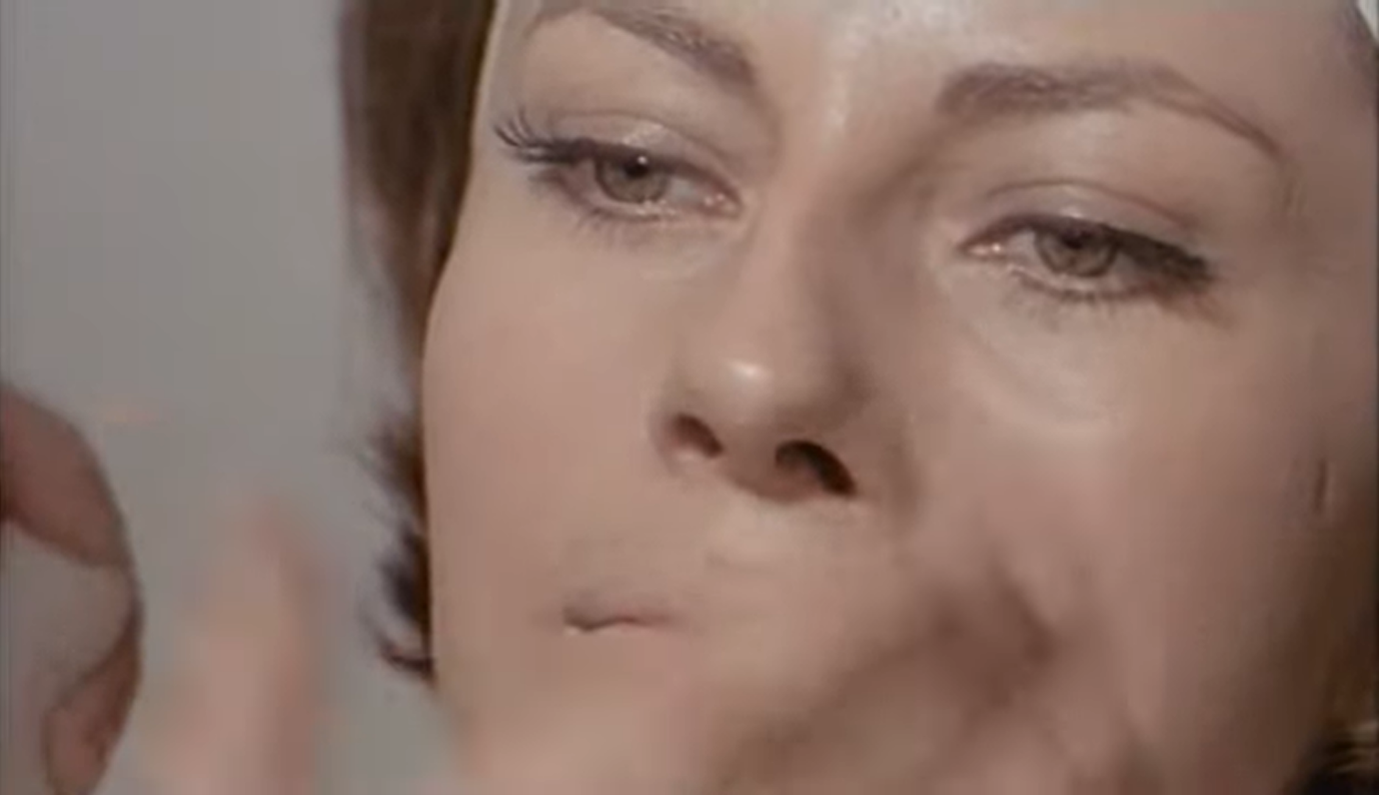

In this respect, the Antonioni character most like Corrado is Princess Soraya in ‘Il provino’. This was a prefatory short film at the start of the three-part I tre volti (The Three Faces). Antonioni’s contribution, which takes up the first 35 minutes of the film, is strangely meandering and plotless considering that it is (presumably) supposed to draw the audience in. Its treatment of the lead actress is similarly alienating. Soraya, who was at this time a well-known public figure but not yet an established actor, plays herself going through the ordeal of a screen-test, trialling different kinds of make-up and wigs, and attempting to occupy the unfriendly space of the film set without losing her sense of self. Looking in the mirror, she tries to wink like Marilyn Monroe; later, on the set, she blinks when the clapper-board snaps in front of her. Both moments feel painful, the first because it is forced and the second because it is involuntary. In neither instance does Soraya seem comfortable with the role she is supposed to occupy.

Clara Manni, in La signora senza camelie, also struggled with the apparatus of acting and film-making, but we were given a vivid sense of her emotional turmoil. In the final moments of that film, when Clara forces a smile for the cameras, we know exactly what she is feeling behind that smile, and if the film works for us we share her feelings.

The same cannot be said of Soraya, whose emotional life in ‘Il provino’ is largely inaccessible. Noa Steimatsky describes Soraya (or this version of her) in the same way I describe Corrado (or Richard Harris), as a person ‘in search of a role’:

Antonioni routinely avoids conventional cinematic mechanisms of identification and tends to diffuse psychology or motivation in tracing his protagonists’ encounters and responses. His best work does turn, however, upon a heightening of perceptual experience filtered, most eloquently, through his female protagonists. But Soraya transmits very little: she resists; the sparse narrative does not evolve nor is it, in Antonioni fashion, diffused through her. All expression seems to bounce off her features and rebound back onto a world of surfaces.4

The word ‘transmits’ is key here, because the film does not suggest that Soraya feels nothing, only that her feelings are not conveyed. One of the most memorable scenes shows her having make-up applied to her face: at first, her eyes are open and seem full of emotion, but the application of the make-up forces her to close them, and we are left staring only at her eye-lids, as opaque and sculpted as those of Pope Julius in Lo sguardo di Michelangelo.

As Soraya explores the film set, she looks through a door that seems to have nothing but darkness behind it, like the attic door in Through a Glass Darkly. There is a reverse-shot from within the darkness behind the door, and Soraya’s face is lost in shadow; then she walks away as the camera continues to watch her from the same position. We see her face as a shadow, or we look at the back of her head – the darkness behind her face, mirroring the darkness behind that door-to-nowhere.

Like Corrado, Soraya has nowhere to go. She is not really ‘in’ the place she seems to be in, which is only a temporary construction, just as she cannot really ‘be’ whoever she is or is supposed to be. As Steimatsky says, ‘it is no simple matter to be oneself (whatever that self may be) in front of a camera.’5 The journalists in ‘Il provino’, despite failing to get the pictures they wanted, will publish their story with the headline, ‘Soraya farà l’attrice.’ The verb ‘fare’ can mean ‘do’, ‘make’, ‘be’, and ‘act like’ – ‘non fare la crettina,’ Linda will say to Mili later in Red Desert – so this headline that concludes ‘Il provino’ captures its protagonist’s ambiguous status. Soraya’s project entails doing what an actress does, making an actress out of herself, being the actress she has made, and ‘acting like’ an actress (implying that she perhaps isn’t one). Indeed, Steimatsky’s interpretation hinges on the fact that this portmanteau film was not a hit and did not lead to a successful acting career for its star:

I tre Volti as a whole seems, in this light, one extended screen test for Soraya: a rather extravagant and ultimately failed one. Il Provino divulges this directly, as a curiously foregone conclusion, exposing its underlying structure and its awareness of the medium while intimating the existential predicament of the aspirant captured within it. This predicament is not rendered as introspection on the part of a character but as imbricated in the very situation of filmmaking, intensified in the screen test, and formalized in Antonioni’s direction of the action, its framing, its mise-en-scène. He foregrounds the analytic, quasi-scientific process by which the test unfolds, also begging the question of what the test is really for. What can the apparatus elicit from the person? Does it hold her together, take her apart? Or might it, intermediately, ease, thaw, or limber her reserve? Whatever the case, does she survive, or do so only as an empty shell, as relic of Antonioni’s probing?6

All these questions – about the screen-test’s effect on Soraya – could be asked about Corrado’s effect on Giuliana (or vice versa), or Frank’s effect on Margaret (or vice versa). All three films, made one after the other from 1963 to 1965, pit individuals against each other and against their environments, and could be read as three variations on a theme. The stakes in each case revolve around Steimatsky’s questions, including the over-arching one about what these ‘testing’ processes are for, what larger codes or structures are in control here, and what happens when these structures are exposed.

I will come back to that issue in Part 16, but for now what interests me is the overlap between Soraya and Corrado as screen-test subjects. In a sense, Giuliana is testing Corrado in the enclosed, controlled environment of her shop, somewhat in the manner of an audition. It is not clear how well Corrado performs in this audition.

Unlike Steimatsky, I do not think ‘Il provino’ labels Soraya’s test as a failure; I think we are left wondering, in a state of mild tension, whether she will succeed or fail, and more importantly whether she wants to succeed or fail. Perhaps we are about to see this inaccessible person come to life and blossom into a star, in which case ‘Il provino’ will have served as a fascinating reflection on the pain and labour that go into such a success, on the distance between a ‘real’ person and their ‘star’ persona. Or, if I tre volti turns out badly, we can retroactively interpret ‘Il provino’ as laying the groundwork for this failure: Soraya’s heart was not in this project to begin with, and all three episodes can be read as reinforcing this point; the film thus becomes a cerebral meta-fiction about non-stardom, La signora senza camelie taken to a new level of sophistication.

There is a similar kind of indeterminacy hanging over Corrado’s audition because we do not know what he really wants, and because he may not know himself. Soraya looks into and then turns away from that shadowy space outside the set; Corrado explores those chilling white walls at the edge of Giuliana’s shop; Frank clutches the hand of a friend and pleads, ‘I can love, can’t I?’

Being able to love, relate, exist, or act, within the space one finds oneself in – this is how one passes the test. But there is a danger that the test itself is un-passable, and that the test subject will inevitably be consumed by an (internal and/or external) emptiness. Even This Sporting Life, for all its nihilism, does not arrive at a definitive conclusion about what happens to Frank Machin, who in the final shot is back on the rugby field, wearing his number-13 shirt, surrounded by hostile voices but still existing and still functioning in some sense.

This lack of closure is part of what gives all three films their haunting quality: they are like courtroom dramas in which the trials never conclude, as though the last page of the script had been left blank. We occupy that blankness, feeling that something is at stake – something is being tested and is in danger of failing – even after we leave the cinema and return to our real lives. This is why it is important for us to return to Giuliana’s shop near the end of Red Desert, not only to ‘conclude’ her relationship with Corrado (in this limited sense we do get some closure), but also to make us feel that something was begun but never finished in this space.

Next week: Part 16, The growth of the affair.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Callan, Michael Feeney, Richard Harris: Sex, Death and the Movies (London: Robson Books, 2003), pp. 133-134

Gilliatt, Penelope, ‘A Great Week for British Cinema’, The Observer (10 February 1963), p. 20

Callan, Michael Feeney, Richard Harris: Sex, Death and the Movies (London: Robson Books, 2003), p. 135

Steimatsky, Noa, The Face on Film (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 187-188

Steimatsky, Noa, The Face on Film (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 191

Steimatsky, Noa, The Face on Film (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 188