Everything That Happens in Red Desert (9)

The 'love' triangle

The plot of Red Desert, such as it is, revolves around the triangular relationship between Giuliana, her husband Ugo, and his friend Corrado. In a much truer sense, this plot is of secondary importance and the film in fact centres on an exploration of Giuliana’s illness, hence the absence of both Ugo and Corrado from the final two scenes. However, the ‘love’ triangle is an important component in delineating Giuliana’s illness: it is a kind of narrative cliché that she is drawn into and that ultimately exacerbates her condition. ‘You haven’t helped me,’ she will say to Corrado in their final scene together, and he will silently walk out of her life. Her first meeting with him contains the seeds of this bleak outcome.

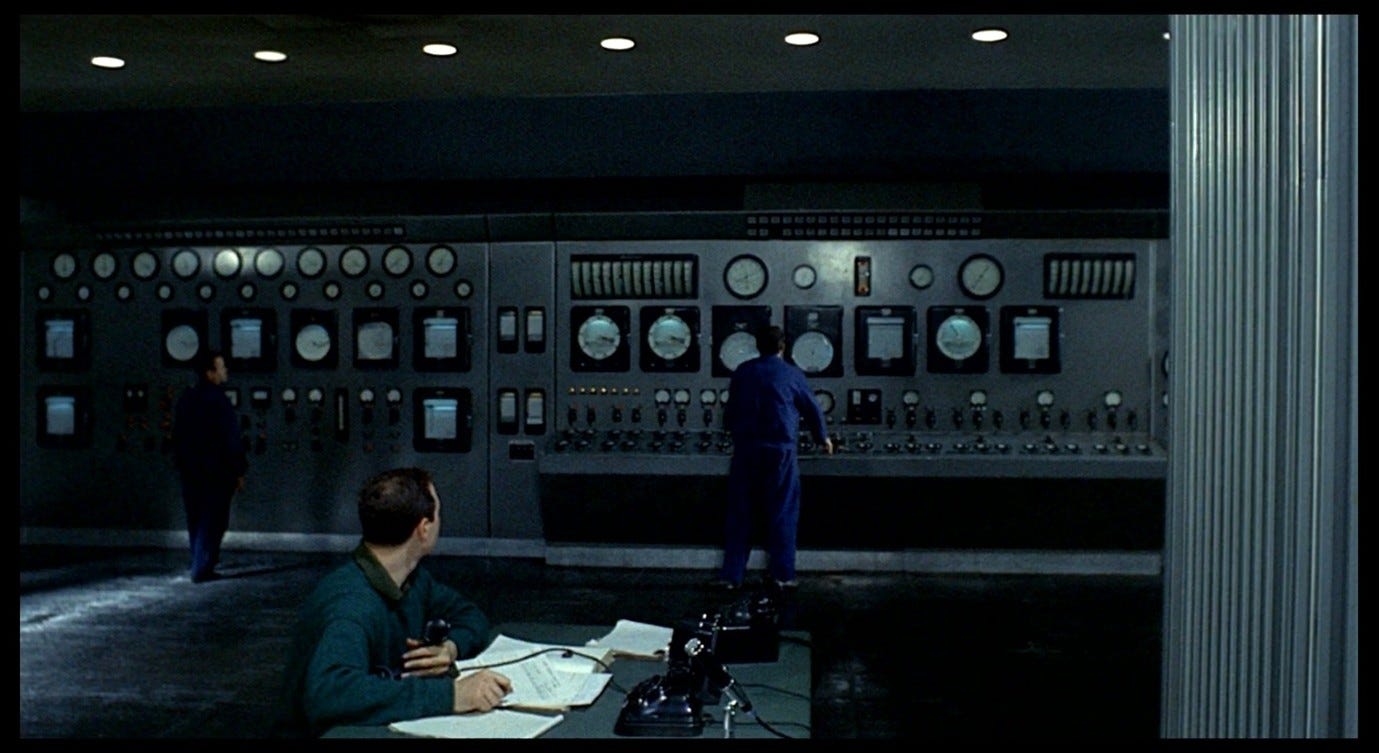

We were first introduced to Giuliana through her lunchtime walk outside the factory. Ugo and Corrado, in contrast, are immediately presented as insiders operating within the industrial complex. There is, again, a nice economy to the establishing shots that place us in the control room:

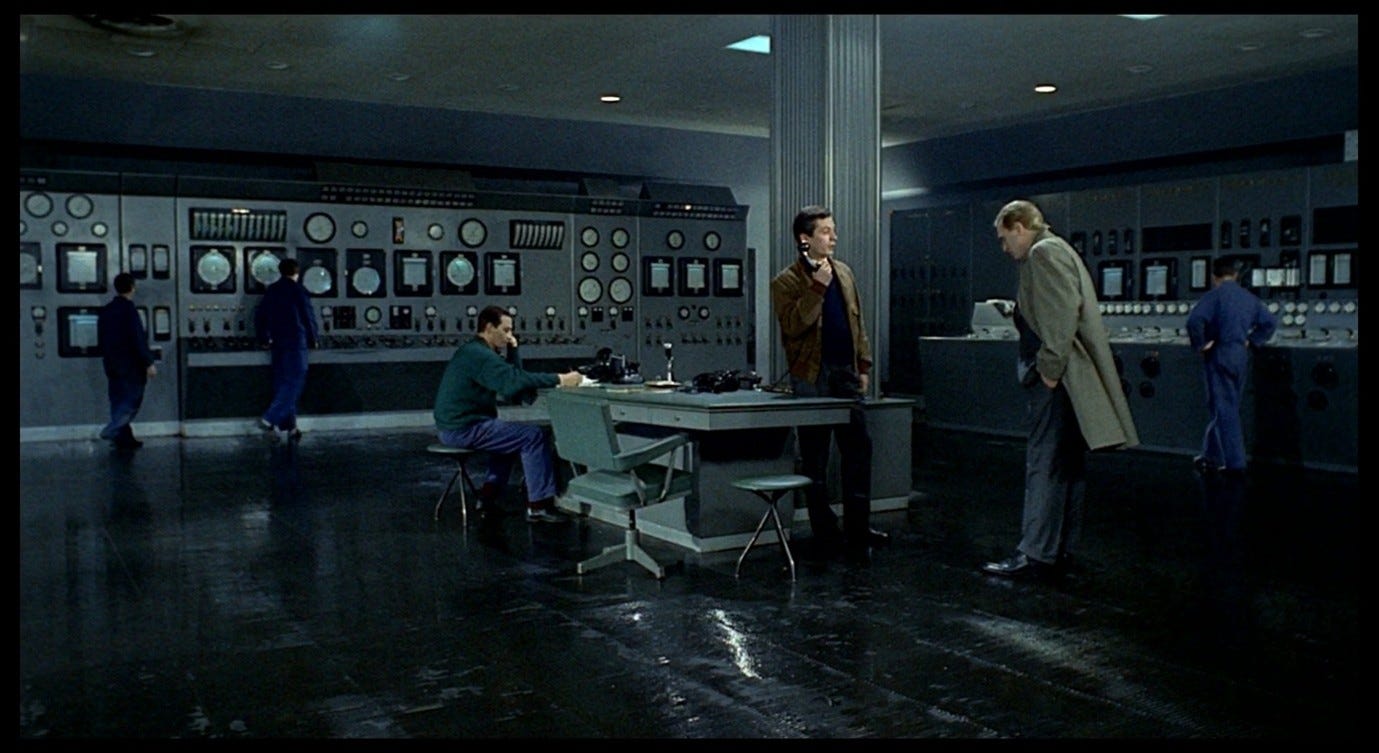

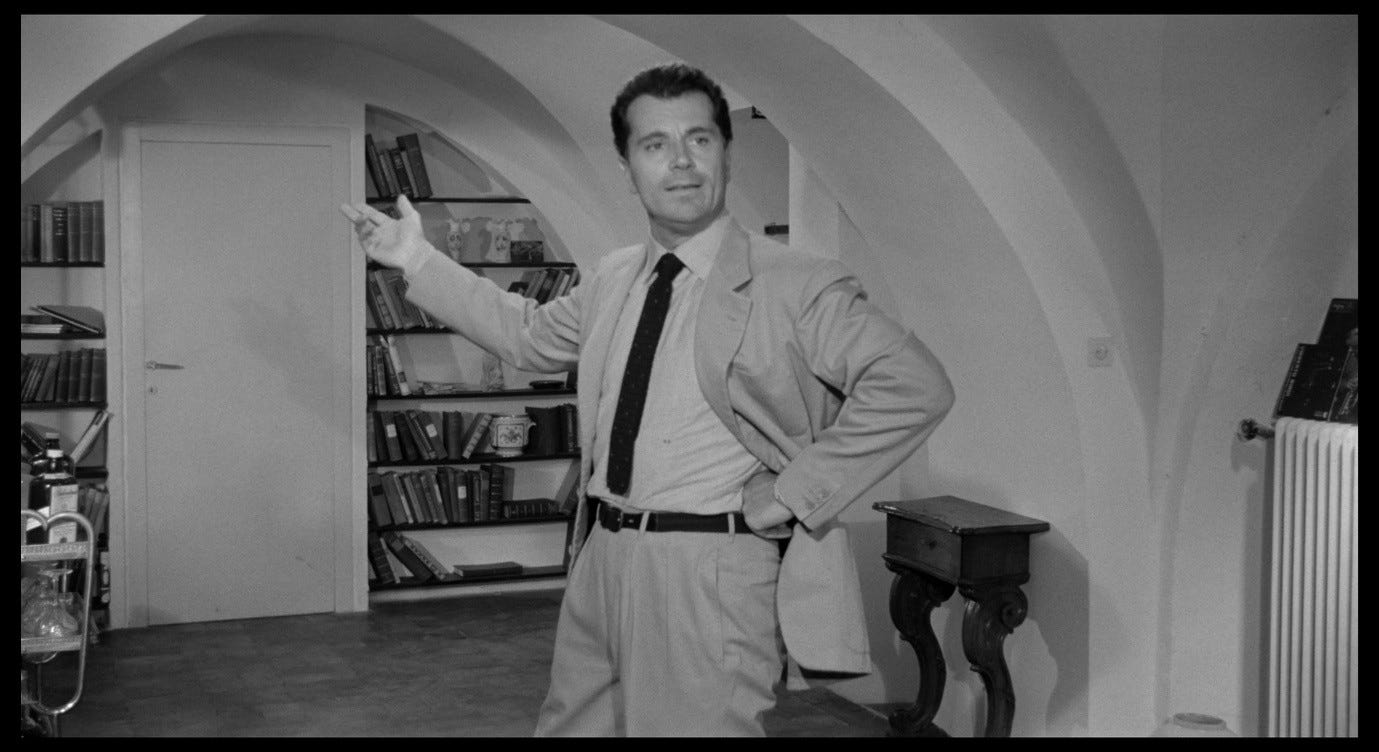

Then establish Ugo as the man in charge here:

And then establish Corrado as the visitor, slightly over-dressed and keeping his coat on:

Several small details tell us about the ambivalent relationship between these two men. On the one hand, they are friendly colleagues. Ugo is helping Corrado to recruit workers for a venture in Patagonia, and is happy to pull strings and provide lists of potential candidates. He calls Corrado an ‘amico’, shows him around the factory, and explains things to him. He shares details about his wife’s accident, her subsequent troubles, and his own feelings about them.

On the other hand, the two men are also marked as rivals. In their first conversation, we learn that Ugo has already told Corrado how hard it will be to recruit workers. He knew something Corrado did not and seems pleased to have been proven right. As Ugo gives Corrado a tour of the factory, he watches his guest’s reactions.

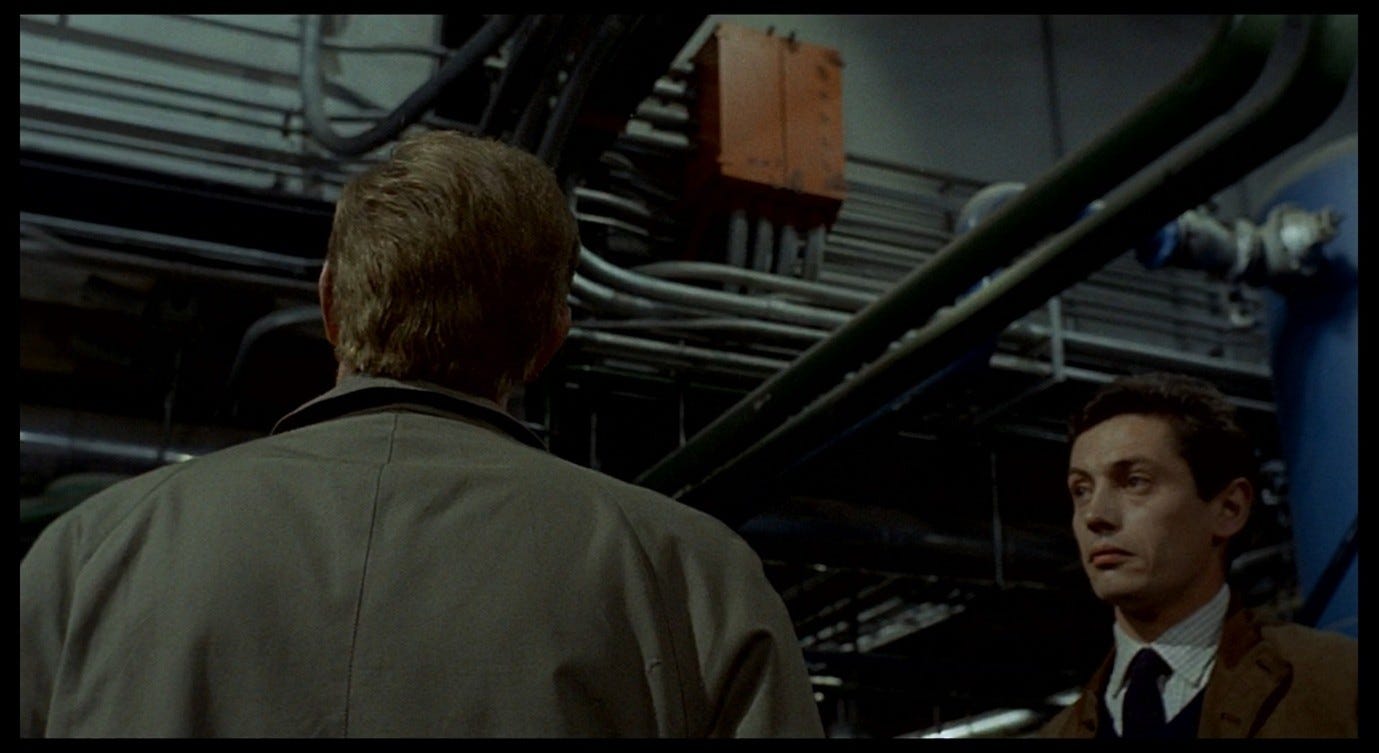

He explains the cloud of steam, forcing Corrado to stop protecting his ears.

In these moments, Ugo displays a mixture of emotions. He is proud of the factory he oversees and wants Corrado to be impressed by it. He also shows some amusement and perhaps even contempt at Corrado’s discomfort. They are both men of industry, neither more senior than the other, but this specific factory is Ugo’s domain, and we get a clear (though subtle) sense that Corrado is at a disadvantage.

Both aspects of this dynamic have a bearing on the triangular relationship that will take shape between these two men and Giuliana. The sense of competition and rivalry is typical for a story of adulterous love. Ugo’s arrogant assumption of superiority makes him unsympathetic, prompting us to question whether he is a good husband while also (in theory) prompting us to root for the underdog who seems more humble and sensitive. A similar love triangle can be seen in Antonioni’s first feature film, Story of a Love Affair. But whereas the impoverished underdog in that film was of drastically lower status than the cold, rich husband, in Red Desert Corrado occupies the same sphere and the same profession as Ugo. He represents a possible avenue of escape for Giuliana, but one that will lead her to the same lonely place she started in. Corrado’s kinship with Ugo hints at this.

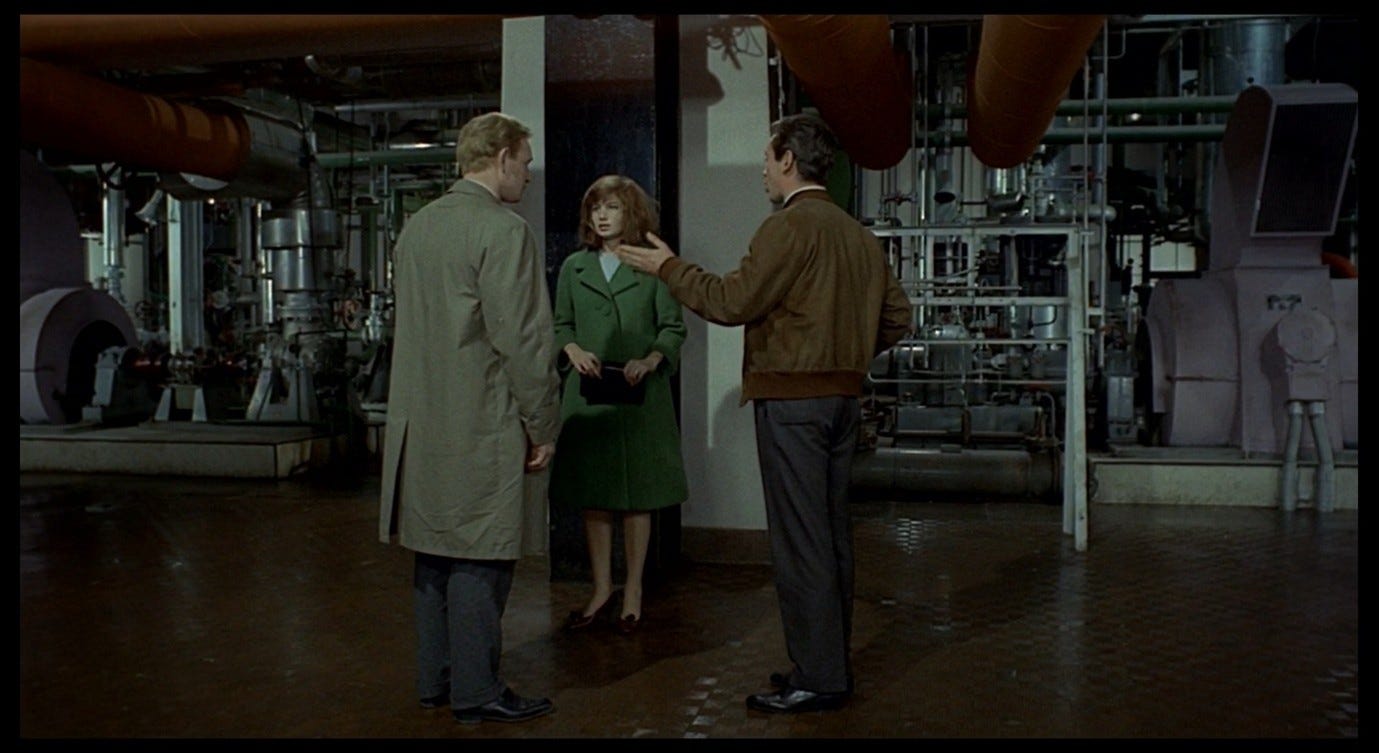

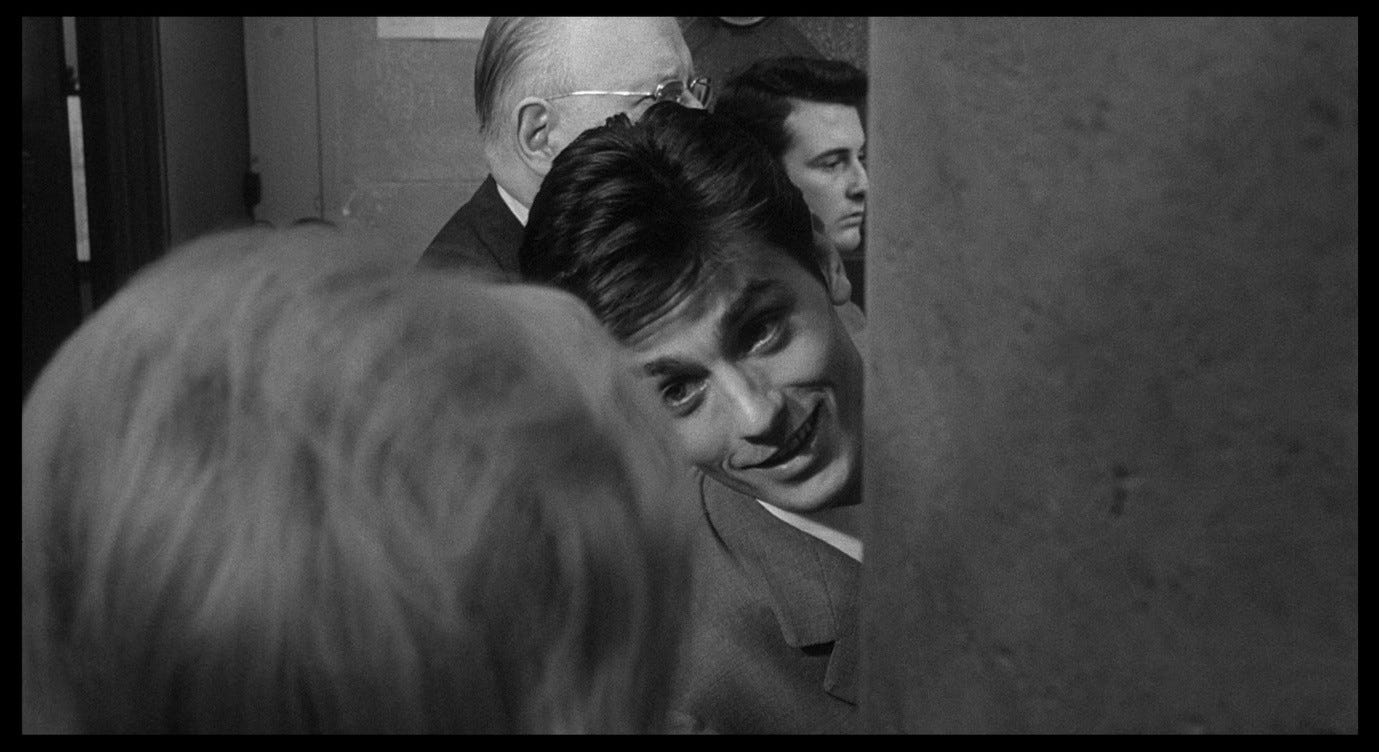

The moment when Giuliana first meets Corrado is loaded with significant details. This is the first time we see her with her husband – the first time we find out how these two characters are related – and what we see implies a rather distant relationship between them. She says, ‘I’ve been looking for you,’ marking Ugo as an ‘unavailable’ husband. It looks like they kiss here, but in fact this is not even a polite ‘bise’: they talk into each other’s ears because they have to in order to make themselves heard.

It is telling that Ugo seems to be in his element in a place where the constant machine-noise renders communication and expressions of feeling almost impossible. Ugo does not ask Giuliana how she is or why she was looking for him; he just tells her to come and meet his friend. The introduction is very impersonal: ‘L’ingegner Zeller. Mia moglie.’ In the screenplay he mentions Corrado’s first name as well,1 but in the finished film he just states his friend’s title and surname; Giuliana is simply ‘my wife.’

Giuliana’s first exchange with Corrado is entirely non-verbal. From the start, they communicate in a way that appears to transcend their unfriendly surroundings. The screenplay says that Giuliana shakes Corrado’s hand ‘con l’evidente intenzione di non perdersi in convenevoli,’2 that is, ‘with the evident intention of not getting lost in formalities.’ Convenire means ‘to be suitable’, so convenevoli are the gestures that are suitable and appropriate in this kind of encounter. Perhaps Giuliana takes her cue from her husband’s impersonal introduction – she thinks this is how he would want her to shake Corrado’s hand – but the clumsiness of the gesture tells us that she has no facility for convenevoli.

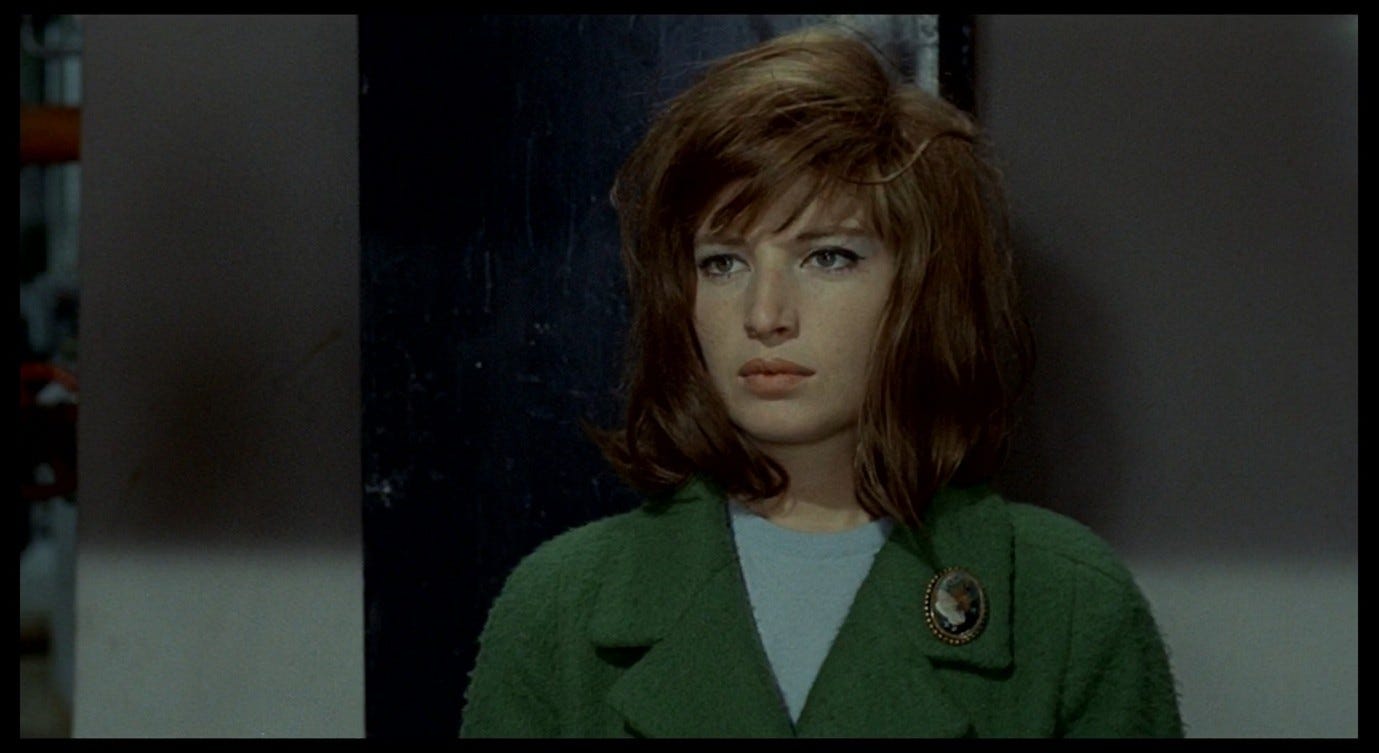

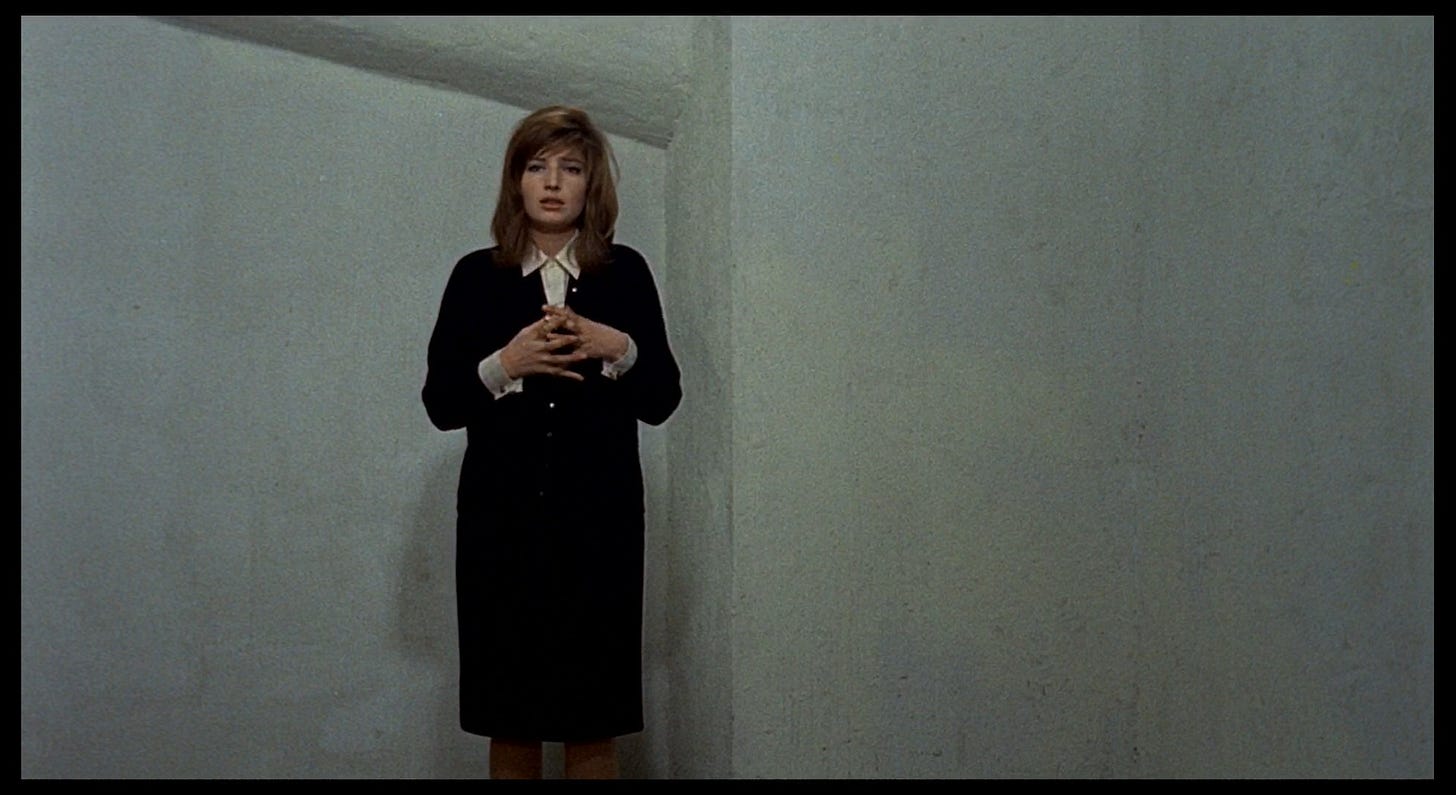

Then Corrado looks at Giuliana with a steady gaze and a half-smile.

She looks back at him, then at her husband, then at Corrado again.

Corrado continues to meet her gaze, a little uncomfortably.

And then his eyes follow her as she enters the frame to stand with her back to him, while she talks to her husband.

Then she glances back at Corrado for a split-second before hurrying away.

To break this down, let’s begin with Giuliana’s stare. First, she seems mildly fascinated by Corrado. There is something about him, or about the way he looks at her, that holds her attention. Her eyes widen slightly but their expression is inscrutable – beyond the fact that she is interested and nervous, we cannot be sure how she feels.

Why does she then look at Ugo? Is she tacitly asking for his approval of the greeting she just offered his friend? Is she self-conscious because she cannot stop herself from showing an interest in this handsome new acquaintance in the presence of her husband? Remembering her awkward interaction with the worker (and with her own son) in the previous scene, we may think Giuliana is trying to orient herself within yet another complex social encounter. What is the relationship between Ugo and Corrado, and where is she supposed to fit in here?

Something about this triangular relationship makes Giuliana uncomfortable, so she breaks the triangle. She has to change position and block Corrado out before she can talk to her husband.

Although she feels an impulse to look at Corrado again, she instantly stifles this impulse and runs away, as if in fear.

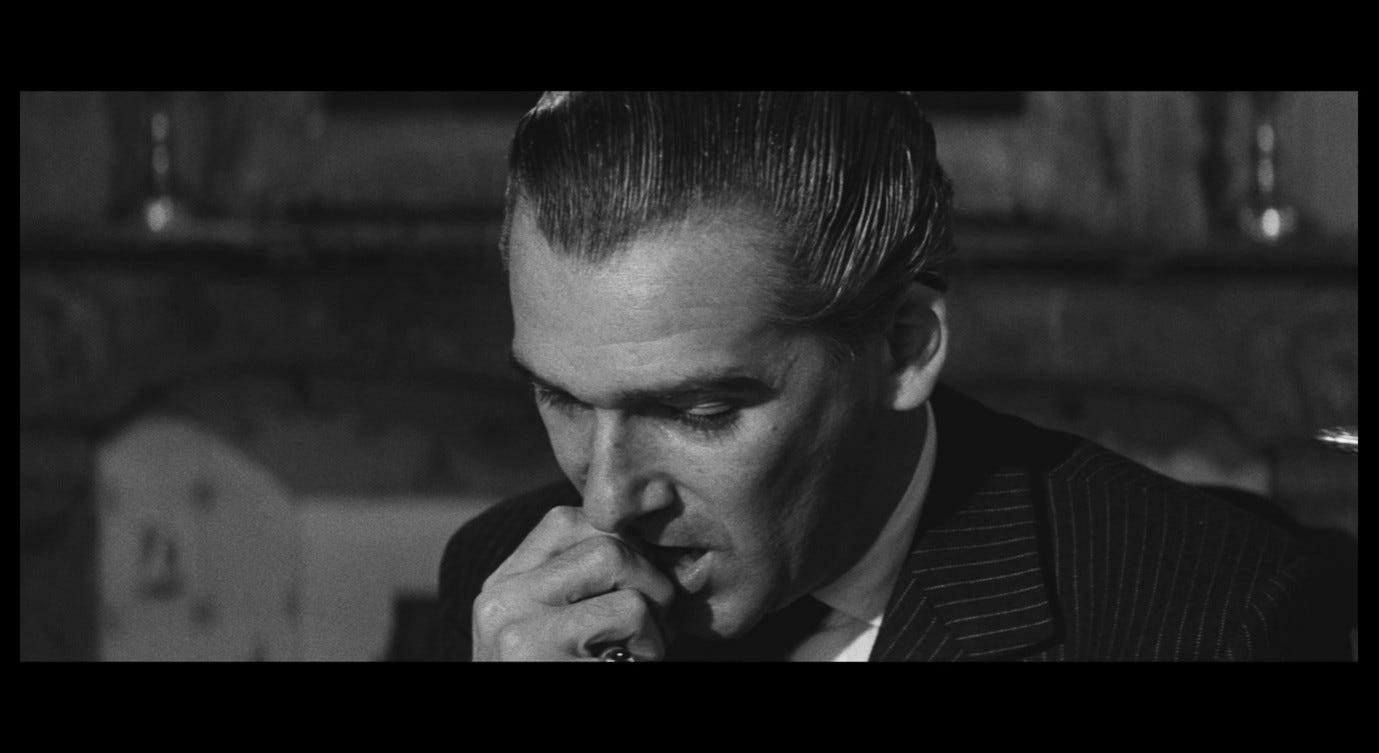

Meanwhile, how do we read Corrado’s stare?

First, there is something predatory about those piercing blue eyes and that insinuating smirk, the mouth slightly agape as if he were about to pay an inappropriate compliment, or as if he were just salivating. Memories of the womanising Frank Machin in This Sporting Life – Richard Harris’s breakthrough role the previous year – may influence our response to him here. In the next shot of Corrado, he has managed to close his mouth and he blinks a little awkwardly, but he continues to stare at Giuliana from behind as she changes position.

He is visibly fascinated and confused by her. In the course of the film, he will ask a lot of questions about her and will ask her a lot of questions about herself. Even in this first encounter, we sense how intrigued he is by her.

We also sense something more primal – his sexual desire for her – and this desire will, at least in my reading, turn out to be the primary basis of Corrado’s interest in Giuliana. This will also end up being a kind of betrayal of Giuliana: a betrayal of what she wants and needs from this relationship. If we see a special bond being formed in this initial encounter, we also see a dissonance between these two characters. The looks they exchange are intense but not quite in tune with each other. Antonioni clearly intended the affair to come across like this:

I would like to emphasize one moment in the film which is intended as a criticism of the old world. When the woman, in the middle of her crisis, needs help, she meets a man who takes advantage of her and her insecurities. They are the same old things that overwhelm her.3

In the original (French-language) interview with Godard, Antonioni refers to Giuliana as a ‘femme en crise’ and says that Corrado ‘profite d’elle et de cette crise.’4 The reference to profit suggests an alignment between this sexual conquest and Corrado’s commercial ventures, while the repetition of the word ‘crise’ (rather than ‘insecurities’) insists on a subtle but important distinction: there is Giuliana and there is the crisis she is in; Corrado does not ‘take advantage of Giuliana and her [internal] insecurities,’ as in Andrew Taylor’s translation, he profits from her and from this crisis she is in.

The original text of the last sentence reads: ‘Elle se trouve en face des vieilles choses, et ce sont les vieilles choses qui la secouent et qui l’emportent.’ Literally, this means: ‘She finds herself face to face with the old things, and it is these old things which agitate her and which carry her.’ ‘Overwhelm’ is a better translation of ‘emportent’ in this context, but I want to underline the idea that what Giuliana is ‘en face’ with when she encounters Corrado (and specifically his sexual desire) is not some kind of erotic liberation, but on the contrary a set of old, outdated conventions. ‘Having an affair’ with Corrado really means being ‘carried away’ by these conventions against her will. ‘I have even succeeded in becoming an unfaithful wife,’ she will say grimly in that final conversation with him.

There are no close-ups of Ugo during the meeting in the factory, even when Giuliana turns to look at him, which would seem like a natural prompt for a reverse-shot of Ugo returning her gaze (and perhaps looking between her and Corrado). We might have seen Ugo smiling complacently or looking suspicious. Either way, a close-up on him would make the encounter less ambiguous. It would imply that there is something here for Giuliana’s husband to react (or fail to react) to, and that we need to see this reaction to follow the story. The fact that we do not see Ugo’s response, and the fact that he seems so utterly blank and neutral when Giuliana then moves closer to him and says that she will wait in his office – ‘Va bene,’ he says casually – suggests that he does not respond at all, that he is virtually absent. This reinforces what the film has already implied: that Ugo is a distant, unavailable husband whom Giuliana searches for without finding.

In Story of a Love Affair, there is a tense encounter between Paola, her husband Enrico, her lover Guido, and Guido’s colleague who is trying to sell Enrico a car.

At this stage in Antonioni’s career, he tended to use long takes in wide shots rather than shot/reverse-shot coverage, so the whole conversation is filmed from a single angle. We see Paola looking nervously at Guido, while Enrico’s attention is mostly focused on Guido’s colleague.

Ostensibly, Enrico is preoccupied with his concerns about the dangerously fast car he has just test-driven, but at the end of the conversation he turns to Guido, asks him what his name is, and shakes his hand.

It seems like a casual pleasantry…but perhaps this is an act. We know Enrico is having Paola investigated by a private detective; perhaps his hesitation about the car suggests that he knows there is something between Paola and Guido. We may see a hint of suspicion in his glance at Paola after shaking Guido’s hand.

We are positioned behind Guido and do not see his face during this conversation, adding to the tension: is he returning Paola’s nervous glances and does Enrico notice that something is passing between them, or is he as blind to Guido’s emotions as the camera is? Once Enrico has left the frame, Guido turns around and steals an intense glare at Paola; she can only make eye-contact with him for a split-second.

In The Lovers, Louis Malle films the illicit lovers on one side of a dinner table while the jealous husband watches from the other side, clearly noticing the tension between them and enjoying their discomfort; they steal glances at each other but he can look at both of them as much as he wants.

Both these examples are typical of ‘love triangle’ cinematography, in that they take care to give the audience a clear sense of the emotions passing between the characters. When information is excluded, as when we cannot see Guido’s face in Story of a Love Affair, it is to heighten our (and the lovers’) tension about the exposure of their relationship.

The scene we are looking at in Red Desert is different because the affair has not yet begun, but the exclusion of Ugo from these shot/reverse-shot glances establishes a trend that will continue throughout the film. We are not asked to see Ugo as jealous or oblivious. When it comes to the affair between his wife and his friend, we are not asked to see him at all. Those scenes in Story of a Love Affair and The Lovers would simply not work without coverage of the husbands’ reactions. In Red Desert, because Ugo is visually excluded even in this first encounter, we understand that his absence is deliberate. Something is missing from this triangle.

The lack of a close-up on Ugo also affects the way we read the wordless exchange between Giuliana and Corrado. If the soon-to-be-cuckolded husband’s reaction would have made the budding romance more obvious, the absence of such a close-up throws that romance into question. Is this love at first sight for Giuliana and Corrado or something more complex, more nebulous? Clearly these two are exchanging ‘significant glances’, but what exactly is being signified?

These glances are easy to make fun of: in Antonioni films, people look at each other, or away from each other, or off into the distance, in vaguely meaningful ways for minutes at a time, without articulating their feelings. Sometimes, his characters emote portentously and then feel self-conscious about it. In the final encounter between Vittoria and Piero in L’eclisse, the two lovers amuse themselves by impersonating other couples they saw at the beach. They parody expressions of erotic hunger:

And deep, meaningful eye-contact:

And then, standing behind a window-veil, Vittoria remembers another couple they can ridicule.

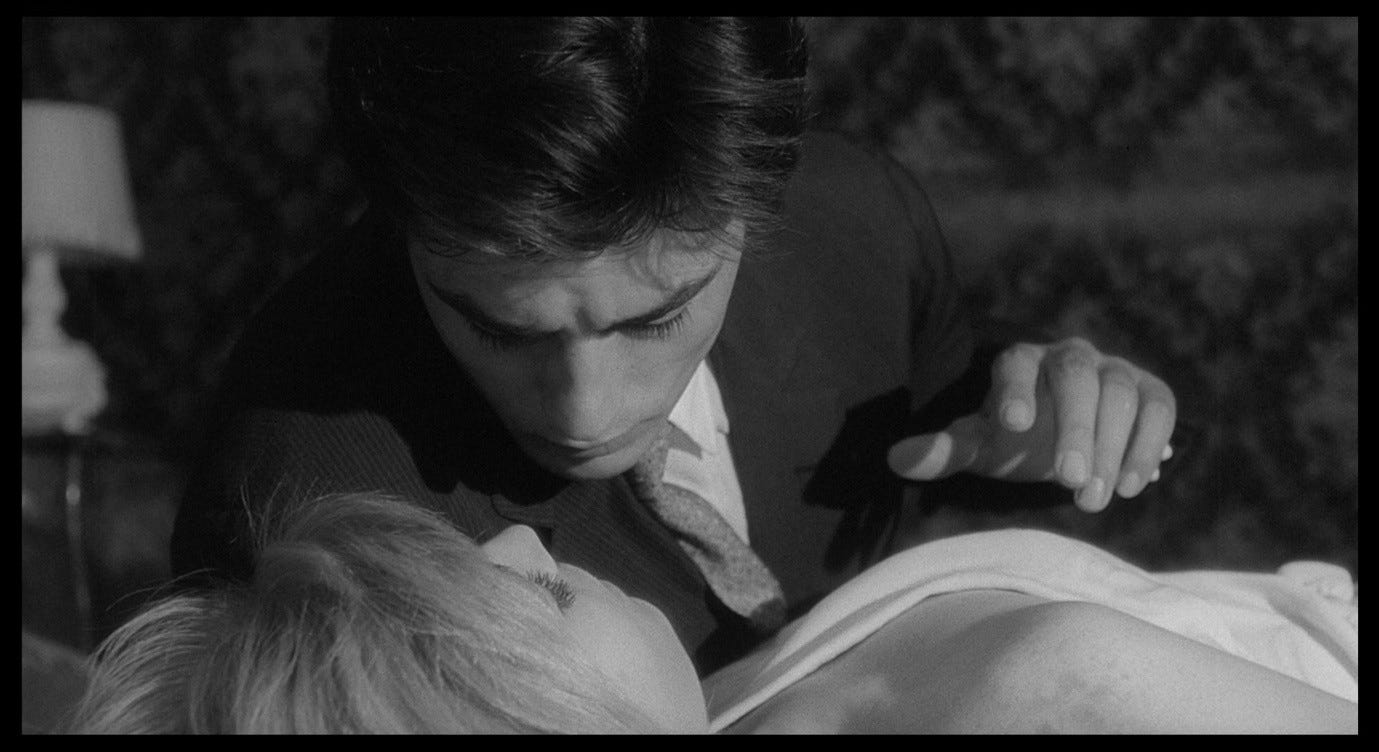

She places the window between her and Piero and they kiss each other through the glass – something they did earlier in his parents’ flat. Here is the original event:

And here is the parody:

In the earlier scene, Piero held his hand over Vittoria in a gesture of predatory desire.

Now Vittoria imitates that gesture but accompanies it with comical growling noises.

They are making fun of their own amorous interactions, and of the non-verbal ways in which they (and others) try to communicate deep and complex emotions. But a minute later, when they are about to part ways for the last time, knowing they will both fail to show up for their date that evening, we see another kind of (easily parodied) significant glance. First, they make deep, meaningful eye-contact.

Then they embrace and look sadly over each other’s shoulders: we see Piero’s expression first, then Vittoria turns her head so they are both facing the same way.

It is the most embarrassingly portentous emotional ‘beat’ in Antonioni’s filmography, and yet it is also heartbreaking; it fees totally sincere even though (or especially because) it feels staged and over-composed. For all the time they have spent making fun of these ‘looks of love’, Vittoria and Piero cannot stop themselves from pulling these ridiculous faces.

Why were those other amorous expressions so funny? Partly because they were pretentious. If two people love each other, or simply desire each other, why indulge in all that gurning, why not just express themselves plainly and simply? If Vittoria and Piero wanted to kiss, why not just do that – why kiss through a pane of glass? The glass kiss occurs in two other Antonioni films, at opposite ends of his career. In La signora senza camelie, we briefly see a couple in the background writing messages to each other on opposite sides of a window pane, then kissing each other through the glass.

In Beyond the Clouds, we see Roberto and Patrizia kiss each other through a glass screen next to the shower.

Wim Wenders, in his book about the making of Beyond the Clouds, observes that ‘[Roberto’s] shadow falls across Patrizia’s face, so that it looks as though he’s kissing his own reflection.’5 The imagery is even more complex than that: first we see Patrizia, vague and distorted behind the glass; then Roberto’s reflection replaces her face as they kiss; then they both pull back from the glass, so that he seems to be looking not at his reflection or at her but at a blank white space (a reflection of the sky outside another window). These lovers are seeing and kissing each other and themselves at the same time; or perhaps they are not seeing or kissing each other, but only themselves; or perhaps they are seeing and kissing nothing. Beyond the Clouds begins with a story about lovers who never touch and never fulfil their desire for each other, which is either a profoundly meaningful comment on alienation or a typically Ferrarese ‘stupid pride or folly,’ as the narrator suggests.

If these poetic looks and gestures are profound (as well as silly), it is because these characters do not ‘simply’ desire each other and are not ‘simply’ in love. Vittoria and Piero look despairingly in the same direction for the same reason they both decide never to meet again. That reason cannot be fully articulated through words. It goes beyond their incompatibility as a couple. Something about the way they look – at themselves, at each other, and at the world around them – means that they are alone. It is like the moment in L’avventura when Anna turns away from Sandro in disgust, then turns away from the camera so we cannot see her face, and then disappears from the film as one shot dissolves into another.

That last image is like the glass kiss in Beyond the Clouds, with one person still solid and in focus, the other dissolving into the grey sky (reflected now by the sea, not a pane of glass). When, not long after this, we see Sandro and Claudia exchanging significant glances – which they did not do while Anna was around – it is as if they are compelled to look at each other, to make eye-contact, and to initiate a relationship, just to deny the significance of Anna’s averted, despairing gaze in the earlier scene.

Sandro and Claudia both know that these looks between them are ridiculous. This is what Vittoria and Piero were truly making fun of and this is what they were truly upset about in their final embrace: don’t these idiots know that such connections are hopeless? Don’t they know that Anna was right?

In L’eclisse, Vittoria and Piero first meet at the stock exchange, greeting each other casually just before the minute’s silence for Piero’s dead colleague.

Piero whispers to Vittoria behind a pillar, explaining that billions of lire are being wasted for the sake of this memorial.

We then get a frontal view of the pillar, with each character’s face half-concealed behind it. Piero quickly moves away from the pillar, meaning that he (like Roberto in Beyond the Clouds) is fully visible while Vittoria (like Patrizia) remains only partially visible.

Like the glass kisses, it is a classic Antonioni image suggesting a paradoxical connection-and-separation. There is a complicity between these two, but embedded in that complicity is the thing that keeps them apart. They make fun of this empty gesture but their relationship is an empty gesture too. At the end, they will be complicit again, in that they both decide not to show up, not to engage in yet more empty gestures. Of course Anna disappeared, and of course the street corner where Vittoria and Piero were to meet remains empty as the evening wears on.

In Antonioni’s next film, Red Desert, the ‘meet cute’ is less cute and less overtly symbolic than the pillar-scene in L’eclisse, but the looks exchanged between Giuliana and Corrado contain a similar kind of despair about the connection-and-separation that will define this relationship. We are, I think, supposed to root for the Claudia/Sandro and Vittoria/Piero couplings, at least a little bit; there is some vestige of that impulse to see people get together that usually drives romantic narratives. But I think Red Desert is devoid of this impulse. The inevitability of the love affair is a remnant of those ‘vieilles choses’ Antonioni referred to in the Godard interview. In this story, the protagonist is ‘en crise’ and there is no clear outcome for us to root for. Nothing about her crisis suggests that she needs to have an affair; at most, we might hope that Corrado will be a friend to her and help her to get better, but even this is never seriously posited as a direction the story could take. Giuliana will look significantly at Corrado, will try to express her condition to him in words and gestures, and will run to him in despair screaming ‘Help me!’ towards the end of the film. But we never really believe he will help.

This is part of what makes Red Desert one of Antonioni’s more challenging and less immediately enjoyable films. If we are tuned in to what is happening, we can respond with pity and terror to the increasingly intense delineation of Giuliana’s illness, but the only narrative momentum comes from our growing anxiety about how much harm she might come to. Corrado is both the catalyst that reveals Giuliana’s inner life to us and a personification of those ‘vieilles choses’ which Antonioni describes as tormenting her and eventually carrying her away. Anna’s alienated gaze at the start of L’avventura, face to face with Sandro after their three-month separation, told us why she would disappear soon afterwards.

That exchange of looks haunts the meeting at the start of Red Desert too. Why introduce Giuliana to Corrado? Why make eye-contact? Why look at each other as though there could be a real connection here? It is so obvious that something is wrong with the way these two (Anna and Sandro or Giuliana and Corrado) look at each other.

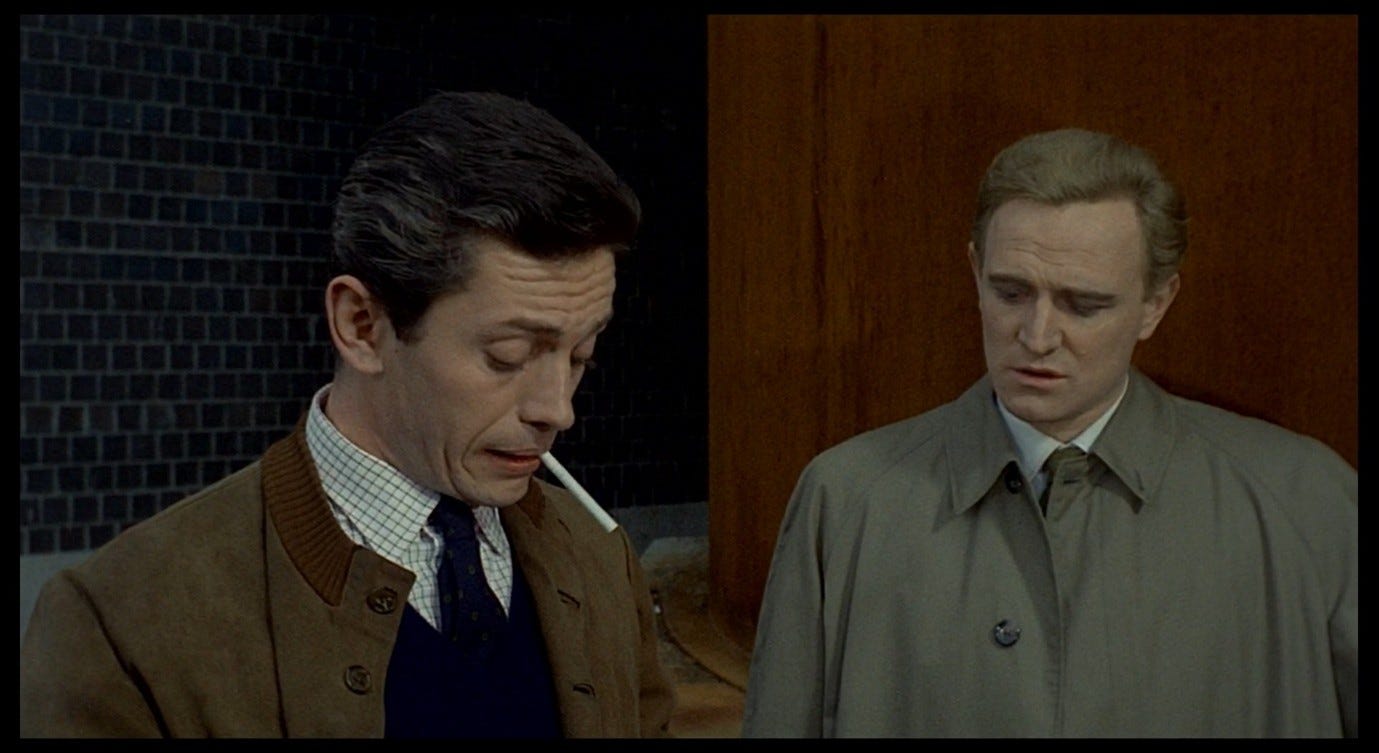

After the meeting in the factory, we follow Ugo and Corrado into the courtyard and find ourselves in the middle of a conversation about Giuliana’s car accident. Either Corrado has asked about her or Ugo has volunteered this information, but one way or another an explanation is required. Giuliana clearly has ‘issues’, and she herself is painfully aware that the two men will talk about her after she leaves: later she will ask, several times, what has been said about her. Like Mabel’s manic behaviour in A Woman Under the Influence, Giuliana’s disruption of social norms needs to be excused and contextualised by her embarrassed husband.

Giuliana will eventually explain that her ‘accident’ was in fact a suicide attempt. But when Ugo talks about it, he plays down the idea that it could have been deliberate. The roads were slippery, he says; she tried to brake; she had only recently obtained her licence; she is always distracted when she drives. The worst of the impact on Giuliana, he says, was the shock – and according to him it was this shock, not her suicidal depression, that caused her illness and put her in the clinic.

There is some impatience in Ugo’s voice when he says that even after Giuliana’s month-long stay in the clinic, ‘she still cannot manage to get in gear [ancora non riesce a ingranare].’6 He pauses to find the right word before saying ‘ingranare’. This verb can be used idiomatically to mean ‘engage’, as in to be engaged with life or to get on with a piece of work. It is used in a mechanical context, to refer to being ‘in gear’: one Italian word for ‘gear’ (i.e. a gear in a machine) is ‘ingranaggio’, and to ‘ingranare la prima’ is to put a car in first gear. In Italian, you ‘insert’ the gear: to ‘inserire la marcia’ is to put the car in gear and to ‘inserire la quinta’ is to put it into fifth gear. Near the end of Red Desert, Giuliana will say ‘I have done everything to reinsert myself [reinserirmi] in reality, as they say in the clinic.’ She is both the driver trying to get the car in gear and the gear itself, trying to insert itself (or allow itself to be inserted) into its rightful place. (‘She’s got a screw loose,’ says Nick about Mabel in A Woman Under the Influence.)

This is significant imagery to use in the context of a car crash. Ugo wants it to sound as though the incident were merely indicative of his wife’s bad driving, for which he dutifully makes excuses. Her ongoing mental illness is similarly downplayed as a mechanical failure, nothing more. He holds his hands up like rotating mechanical claws, trying but failing to slot into place. Giuliana will mesh her fingers together when she uses the word ‘reinserirmi’ later on.

For Ugo, Giuliana is a machine that is not functioning properly. She wants to open a shop but this does not seem ‘decoroso’ (decorous, appropriate, convenevole) to Ugo. Corrado asks why; Ugo simply shrugs in response. There is an unwritten law that says a woman in Giuliana’s position ought not to open a shop. This should be understood intuitively and accepted without question.

In these opening scenes, the film has repeatedly underlined the importance of decorum and the embarrassment attendant upon any violation thereof. Giuliana’s embarrassment when purchasing the sandwich or meeting Corrado is guileless and overt, but her husband’s embarrassment is expressed indirectly, through shrugging gestures (primarily via the mouth and eyebrows), distractions like lighting a cigarette, and a tendency to look away from Corrado.

Whether Corrado initiated this conversation or not, he seems genuinely curious about Giuliana and genuinely troubled by Ugo’s account. He furrows his brow and keeps asking questions – a habit that will eventually come to annoy Ugo. Ugo may not be able to look at Corrado, but Corrado looks at Ugo very intensely, watching his hands as he makes the ‘ingranare’ gesture and as he lights his cigarette, scanning his face to read the emotions behind this studiedly casual performance.

Giuliana will later tell Corrado, ‘If Ugo looked at me the way you have in the last few days, he would have understood many things.’ Even in their first encounter, Corrado’s searching eyes have found something in Giuliana that Ugo does not see. We already get the sense that he may be judging Ugo for not seeing these things, for talking about his wife in such mechanical terms, for being so cool about her illness that he can shrug and light a cigarette while discussing it, and for being snobbish about her desire to open a shop.

We are getting more and more of a sense that something is going to develop between Giuliana and Corrado, but that sense is an uneasy premonition rather than a hopeful desire. David Forgacs argues that these two characters are drawn to each other because they are both out of place in their environment:

Corrado is an insider who is also a bit of an outsider. […] Unlike Ugo, he’s ill at ease with his own life, restless, and sensitive. These characteristics will account for the interest he takes in Giuliana, who is deeply uneasy with herself and her surroundings, and will also explain why she becomes drawn to him.7

However, as Forgacs says later in his commentary, there are other dimensions to Corrado’s interest in Giuliana which ultimately create a gulf between them. Throughout the rest of the film, we will see how these two characters are brought together by things they have in common, but we will also see a persistent emphasis on their insoluble differences.

Next: Part 10, Night terrors.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 439

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 440

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, trans. Andrew Taylor, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; p. 291

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘La nuit, l’éclipse, l’aurore’, in Cahiers du Cinéma 160 (November 1964), pp. 8-17; p. 15

Wenders, Wim, My Time with Antonioni, trans. Michael Hofmann (London: Faber and Faber, 2000), p. 129

The published screenplay gives the word as ‘riingranare’, which would strengthen the echo of this conversation in her later use of ‘reinserirmi’ (see below). Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 441

Forgacs, David, Commentary track, Red Desert (Blu-Ray, BFI, 2008)