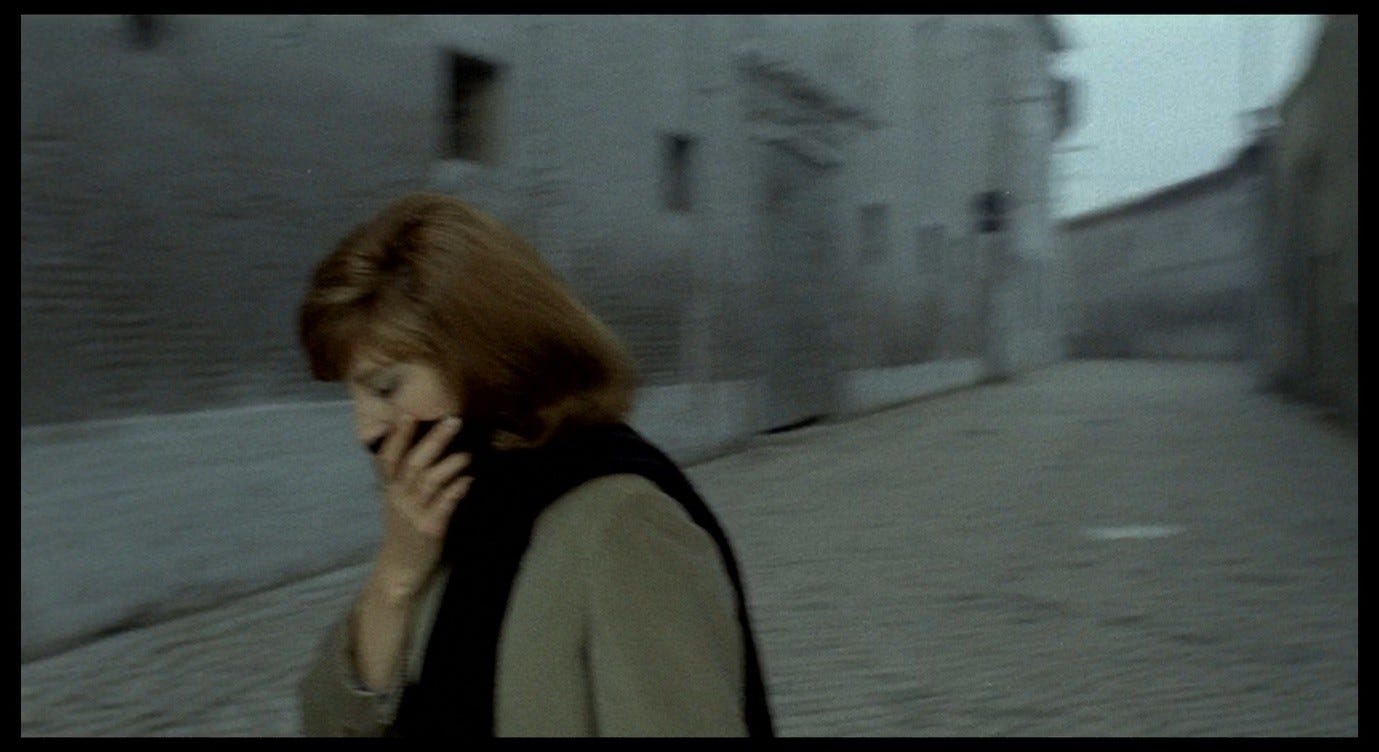

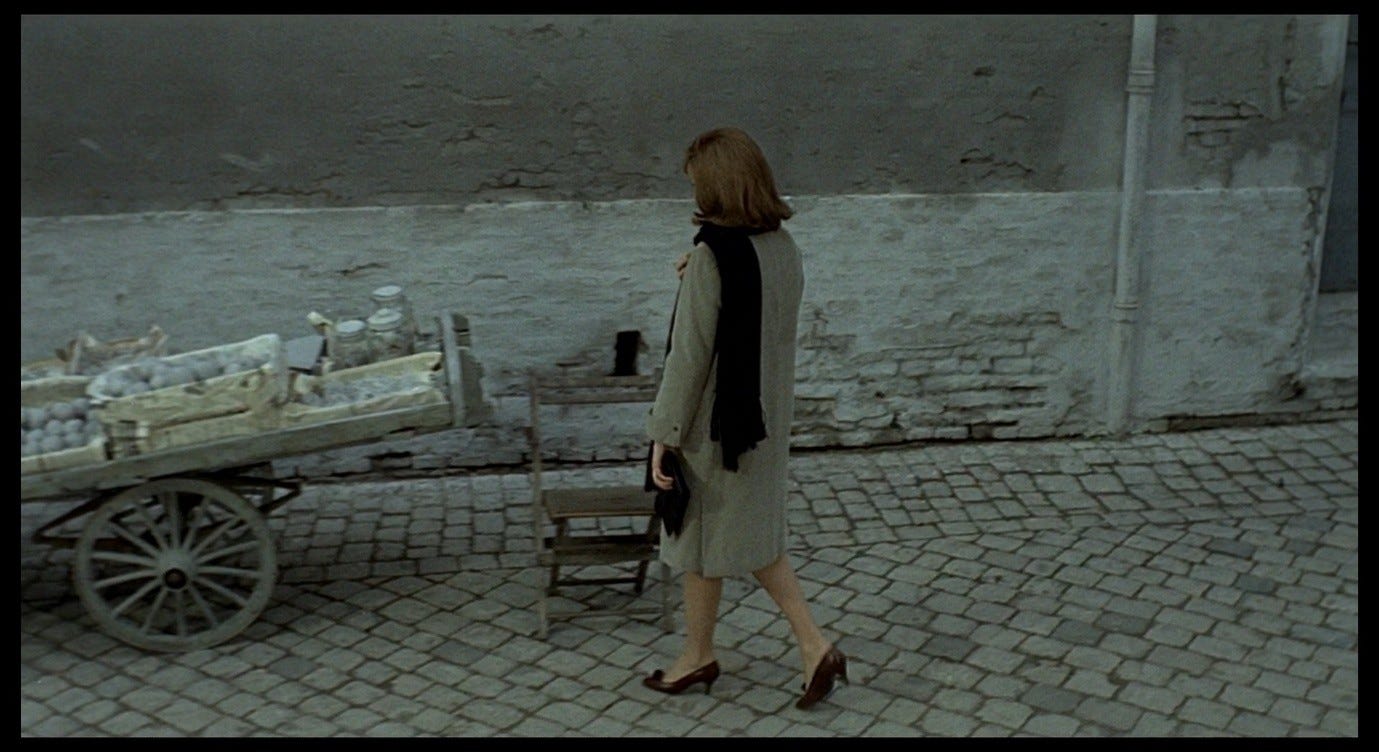

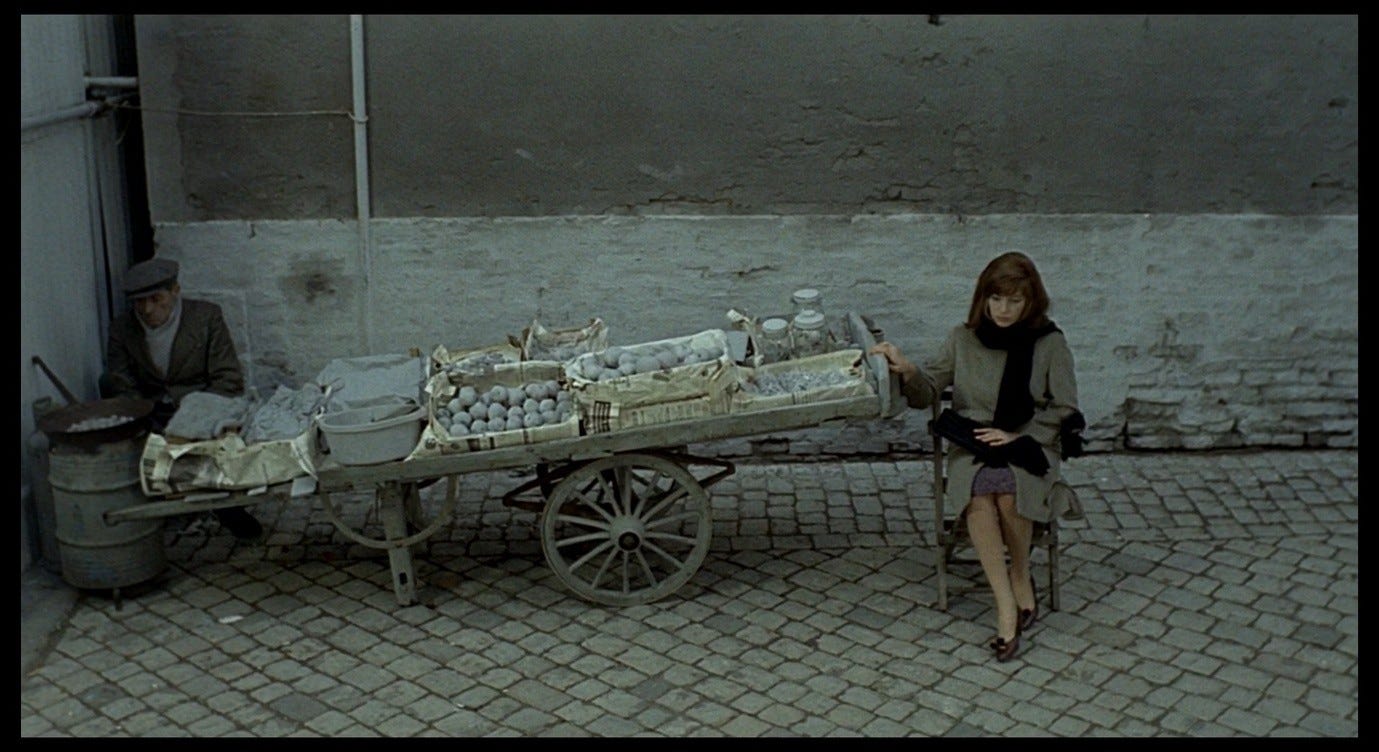

Just after watching the newspaper (from ‘today’) drift down the street, Giuliana looks at her surroundings and wraps her scarf over her mouth for warmth. Corrado opens the door of his car as though expecting Giuliana to go somewhere with him, then furrows his brow at her as she nervously darts her eyes in the other direction. She moves away from him and we follow her (in a tracking shot) until she sits down beside a fruit-cart, which is presumably what her eyes were darting towards, but which we are seeing for the first time. At the other end of the cart, the vendor is roasting chestnuts in a large pan. Perhaps Giuliana was drawn to this source of warmth as well as to the prospect of resting in the empty chair by the cart.

There is, however, not much rest or warmth to be had here. As the camera tracks left and pulls back to capture the full tableau, the sudden appearance of the fruit-cart and its owner has an unsettling effect. We recognise the objects…then we realise they are all (or almost all) grey. It is like the moment in a nightmare when a familiar object or place seems suddenly ‘off’. It might make sense for the chestnuts to be grey if they have been over-roasted and coated with their own ash. The greyness of the roasting barrel, of the seller’s scarf and cap, and of the walls and the street, could also be more-or-less normal. It is perhaps a little odd that the cart itself is entirely grey, and that some of the containers and coverings on the cart are the same shade of grey. When we notice that the fruit is grey as well, as though all of it had been roasted along with the chestnuts, we may start to question our grip on reality. And finally, when we see a close-up of the fruit-seller’s face and it too seems to be turning grey, this clinches our impression that reality is out of joint.

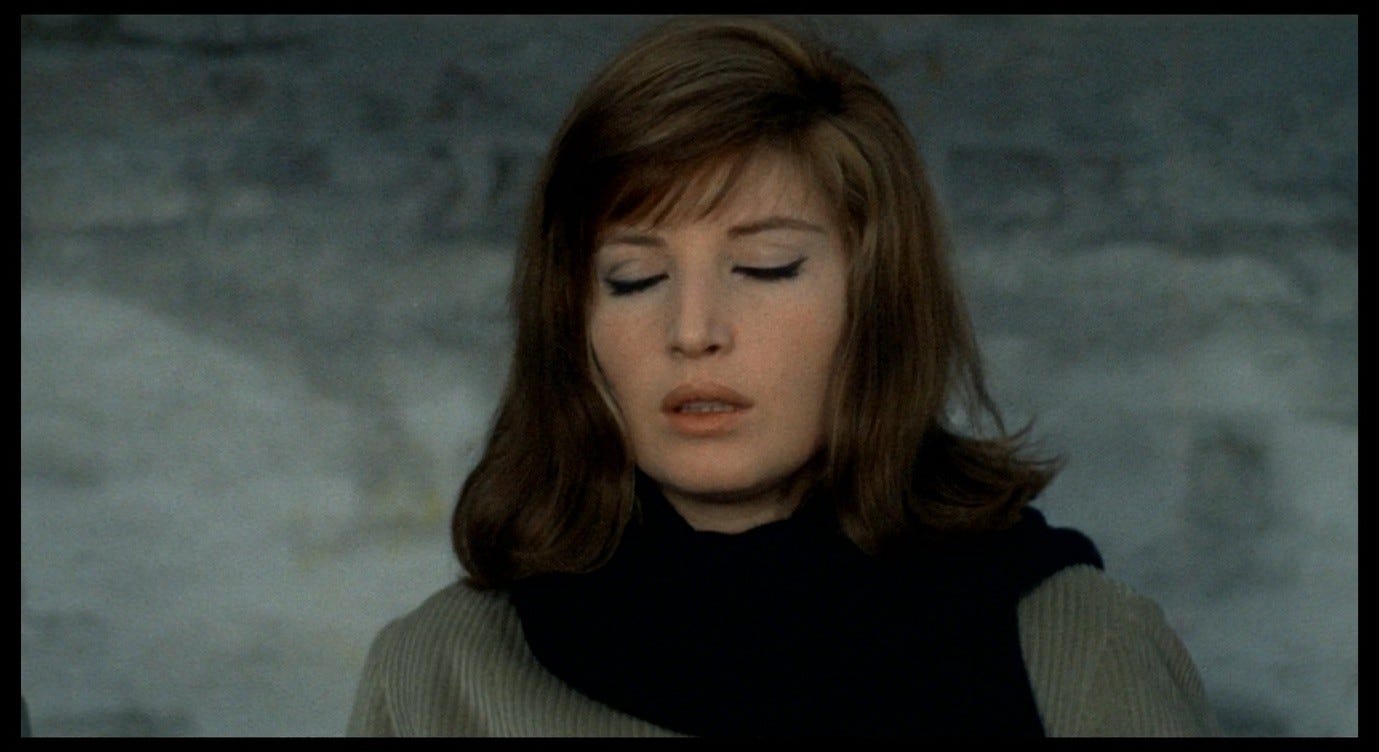

Giuliana seems faint, her eyes on the verge of closing, her head lolling, her mouth struggling to form words.

Corrado asks her whether she is tired, but what happens next indicates something worse than fatigue. The ominous electronic roar on the soundtrack, similar to the resonant nightmare-sounds we heard during the previous scene (in Giuliana’s home), heralds another impending danger. We cut from Giuliana to the fruit-seller, stirring his chestnuts, his grey fruit captured blurrily in the foreground by the telephoto lens.

He turns from the chestnuts to look at Giuliana, a deep scowl showing up the lines in his face, which are also accentuated by the grey make-up.

In the next shot, we see Giuliana’s head from behind and realise that she is looking at the fruit-seller.

The film could have shown her turning to look at him, then cut to him turning his head, but the normal grammar of shot/reverse-shot is subverted. We do not know who looks first or who turns in response. The subversion continues as we are deprived of a reverse-shot of Giuliana’s face – we only see the back of her head – and as we are left unsure of what Giuliana herself is seeing. If this shot represents her perspective, she is again seeing the world out of focus: she does not see this man as a man, but as a vague shape merging with other shapes. She cannot make eye-contact or otherwise communicate with such a shape, so we can only imagine the perplexed, wandering stare the fruit-seller may be faced with. When we see him again, this time in focus and from a closer angle, we are perhaps seeing what Giuliana cannot, or seeing how she cannot (in focus).

The fruit-seller bristles, still scowling, looking from Giuliana to Corrado, offended by the gawking of these two interlopers – why won’t they leave him alone? Then the camera steps back so that it is looking over the shoulders of both Giuliana and Corrado, who are both looking at the fruit-seller. His attention turns back to the chestnuts.

Giuliana quickly turns to look the other way, towards the camera. Again, she seems to anticipate an approaching threat.

The electronic howling-wind noise on the soundtrack reaches a pitch and then gradually dies away as we cut to a reverse-shot of the empty grey street.

On the one hand, there is nothing there – no danger. On the other hand, there is something uncanny about the absolute victory of greyness in this image. Everything is grey now, from the sky downwards, albeit with some tonal variations towards white, black, brown, or green. This is the only shot in this sequence that contains no signs of life. It is the moment that most clearly recalls the empty town in L’avventura, discussed in Part 12. But in contrast to Schisina’s pristine white buildings, perfectly preserved having never been lived in, the Via Alighieri feels abandoned and neglected.

Unable to see around the turn at the end of the street, Giuliana cannot guess where it leads or what might emerge from it, but either way the lead-in to this shot makes us feel that there is something threatening around that corner. In L’avventura, a similar sense of menace was created by the un-motivated dolly shot that prowled through the empty town after Claudia and Sandro escaped, suggesting that there was some creeping thing in this place – something to be escaped from.

In Red Desert, Giuliana is more trapped and helpless, caught between the phantom remnant of this old world (the fruit-seller) and the unknown entities she will encounter if she leaves (at the other end of the grey street). Besides its associative power, the colour grey is tonally appropriate here. It helps to conjure a mood of inertia, depression, and liminality, of a fading world and fading consciousness.

The surreal greyness of the fruit-cart suggests that, for at least some of this sequence, we are seeing the world through Giuliana’s distorting vision, rather than as it ‘really is.’ Seymour Chatman refers to the ‘remarkable double vision’ in the fruit-seller sequence,

through which we see alternately from Giuliana’s point of view and from the camera’s own. […] In the first stage, everything in the background is fuzz; in the second stage, everything is clear. The first stage of the shot corresponds to Giuliana’s vision; the peddler looks unclear and distant. But the second stage conveys the camera’s own more neutral reality: the peddler is simply one more thing in the street to be seen. Putting him into focus reestablishes a correct, unneurotic, unintense perspective.1

On its own, the series of in-focus and out-of-focus images as Giuliana looks at the fruit-seller would seem to support the idea that we are alternating between correct and incorrect perspectives. But then Giuliana looks the other way. What she sees is not blurry at all: it is in focus, and it is as grey as the in-focus face of the old man, which is as grey as the fruit when seen in a perfectly focused wide shot. So why not say that both images of the fruit-seller – the blurred one and the crystal-clear one – represent Giuliana’s perspective? The peddler cannot be ‘simply one more thing in the street to be seen’ when he and his produce are so strangely grey, any more than the vision of the strangely empty street can be dismissed with the matter-of-fact verdict that there is ‘nothing there.’

John Orr grapples with the ambiguity of these focus-effects, but (deliberately) does not resolve it:

In framing Vitti by the stall in long shot, the sequence has a clinical objectivity, but the artificial grey colour of the fruit echoes the grey colours of Ravenna’s industrial landscape. It is as if the fruit has been seen through Vitti’s eyes, yet she herself is in the frame. Subjectivity is conveyed through the objective shot, not through the POV shot. This has a strange effect, a mind-distortion […] The over-the-shoulder shots of Vitti with a telephoto lens have the back of her head in clear focus but make her visual field seem blurred and immediate, pressing in upon her as if her unseen eyes themselves cannot clearly see what confronts them. We have simultaneously, subjective vision and a clinical distancing from it.2

This reverses Chatman’s ordering of the ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ perspectives. According to Orr, it is when we see in focus (the grey fruit-cart, fruit-seller, and street) that we are looking through Giuliana’s distorting eyes. When we see the fruit-seller out of focus, over Giuliana’s shoulder, this represents a kind of ‘clinical distancing,’ a way of saying, ‘this woman’s eyes cannot clearly see what confronts them.’ It seems (incorrectly) to Giuliana that she is seeing everything clearly, and that everything has turned grey; but the over-the-shoulder image portrays her visual field (correctly) as blurred. In short, she thinks she can see her environment but she cannot.

As I have said before, I do think that Red Desert allows for a ‘clinical distance’ in some of its imagery, a sense that we are sometimes seeing things exactly as Giuliana does and sometimes seeing them as the ‘well adjusted’ characters would see them. The word ‘clinical’ is appropriate: when we see Giuliana (in focus) seeing the world (out of focus), this echoes the lesson which, as we will learn later, Giuliana has been taught in the clinic, about her dysfunctional relationship with reality. The differences between Chatman’s and Orr’s readings demonstrate why it can be unhelpful to try and disentangle the ‘correct’ from the ‘incorrect’ mode of seeing. The film signals to us that these two modes of seeing are available, and that they are different, but it does so through the consciousness of Giuliana. She is conscious of these different perspectives but unable to inhabit one or the other in any stable way. At one moment, everything and everyone looks grey; then she tells herself, as they would in the clinic, that she is seeing incorrectly, blurrily, that she needs glasses; but then the old man is still there, in focus, grey and frightening; and when she looks the other way, she sees with perfect clarity the Via Alighieri as the gently shrieking abyss she knows it to be.

As Orr says, we thus get multiple perspectives at once, resulting in a ‘mind-distortion.’ We can say that Giuliana is neurotic and that the film is diagnosing her illness as well as visualising it directly. Or we can say that we are sharing her insight into the ‘something terrible in reality’ that lies beyond the surface of the photograph-able world, and that the clinical voices repressing this insight are themselves part of that ‘terrible thing’: ‘You shouldn’t think about such things,’ Corrado will say at the end of the film, prompting a memorably sarcastic response from Giuliana. It is useful to remember (so to speak) that she will insist on being so combative in the face of Corrado’s patronising, normalising advice. Red Desert has been inducting us into this complex way of seeing things through various methods – blurred images, discoloured vegetation, inexplicable close-ups of pipes and steam-clouds, disturbing noises on the soundtrack – but there is something new in the confrontational use of greyness in the present sequence. This will help to prepare us for the more intense confrontations in the latter part of the film.

The fruit-seller was played by a non-professional actor named Tanino, recruited from a local rest home. In assistant director Flavio Niccolini’s diary about the making of Red Desert, there is a telling description of what happened when the fruit-cart scene had finished shooting:

At the cut, Monica [Vitti] turns around, says to us: ‘he’s frightening.’ Maybe this is what Tanino wants: to frighten, for the last time, before disappearing into the absolute zero, in the physical and spiritual starvation of the old folks’ home in via Roma. Antonioni turns to me smiling, satisfied and sly: I’m sure that between him and Tanino there’s a secret and reciprocal creative satisfaction, a shared sense of the tragic revelation of truth.3

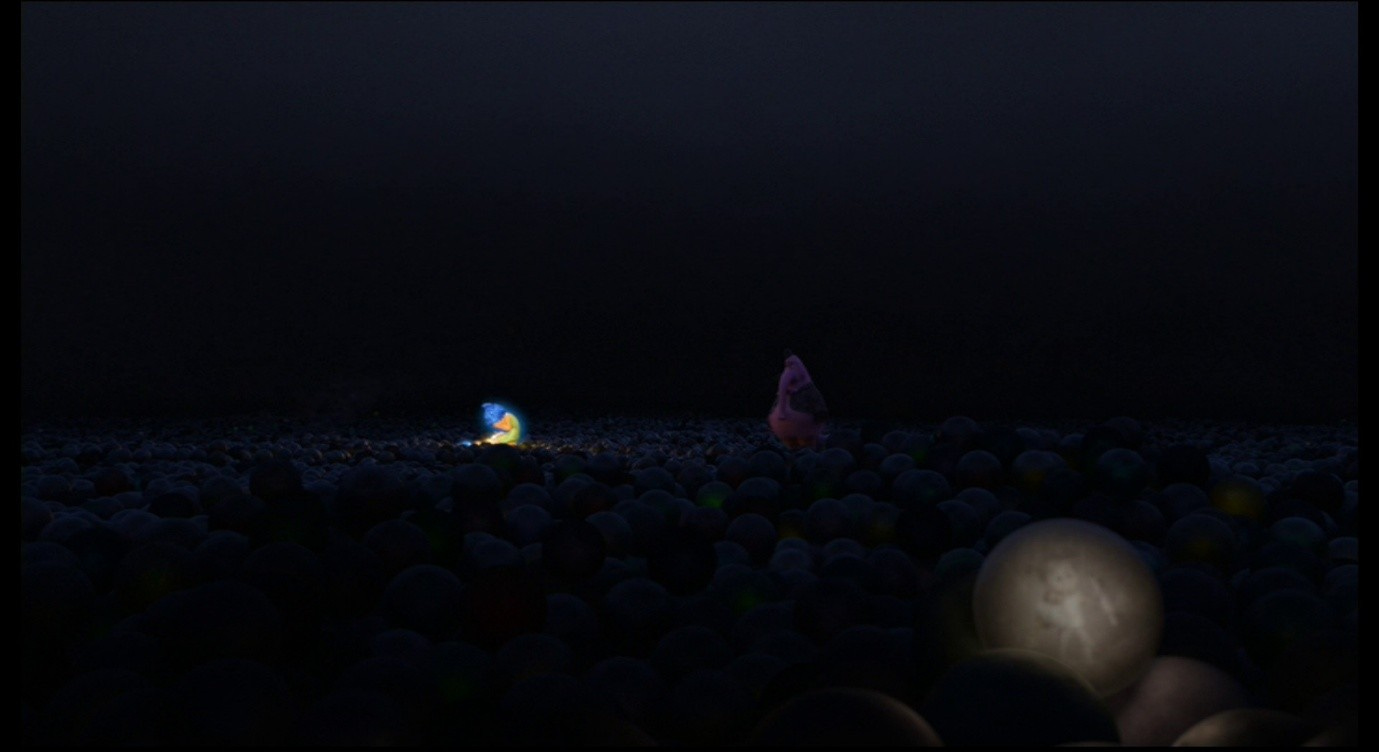

What we see in this sequence is a world on the verge of disintegration, about to disappear into ‘absolute zero,’ like the all-grey pit in Inside Out where memories are discarded and turned to dust. At that point in the film, Riley is walking along a bleak, grey street not unlike the Via Alighieri. The end of the street is obscured by fog, and Riley is very deliberately walking into that fog. Meanwhile, the allegorical drama in her mind shows Joy, lost in the pit, cradling memories of childhood happiness as they disintegrate. Perhaps this is the moment when we first notice that Joy herself is a creature in flux, her luminous yellow flesh haemorrhaging tiny particles that vanish like the dying memories. If left in a place like this for long enough – if this crisis were more severe, and if Riley’s mind were not equipped to resolve it – Joy could disappear forever. Indeed, she inevitably will, when Riley dies if not before.

In the slag-heap sequence in Red Desert, we saw objects and trees that had been eaten up and turned black by industrial processes.

But the greyness of the Via Alighieri represents a different kind of refuse. Instead of factories burning the world black, we see chestnuts roasting for too long, charred beyond blackness into powdery grey ash. The ash is suggestive of dust, and the layer of greyness that covers everything seems as much a sign of age and decay as of combustion or pollution. Primed by earlier scenes to understand how the factories sully the world around them, we sense that this street may have been turned grey by clouds of smog or ash drifting onto it – Karen Pinkus likens it to ‘post-nuclear ash’4 – but at the same time we sense that it has simply been neglected and allowed to accumulate dust: we can read the greyness in both ways at the same time.

The newspaper that floats in from ‘today’ and falls dead on the grey cobbles is linked immediately with the fruit-cart, when Giuliana turns from the one to the other, and we see that some of the containers on the cart are wrapped in newspaper. The re-use of newspapers to wrap street-food is a proverbial metaphor for transience – ‘Tomorrow this’ll be yesterday’s paper and they’ll wrap a fish in it,’ as Charles Tatum says in Ace in the Hole – and one effect of this sequence is to show that Giuliana’s shop is located in a place that has been discarded, relegated to the past. The isolation of the street is accentuated by the corrugated iron board next to the fruit-cart. This may already have been there when the scene was filmed, but it may well have been added deliberately, because without it the scene would be less claustrophobic. A Google Street View image reveals a three-way junction that would have created an unwelcome sense that there are other places we could go if we wanted to escape.

(As proof that this is the same corner, note the horizontal lines on the corner-wall in the Google image, which are also briefly visible in a shot at the end of the Red Desert sequence.)

The street is blocked off at one end and vanishes into oblivion at the other. It could easily be an allegorical setting for an encounter with the ‘end of the line,’ with mortality.

But Giuliana’s fear stems from something more complex than the mere prospect of transience and decay. Niccolini suggests that this old man, as an inhabitant (and representative) of the old world, wants to give one last fright before he disintegrates, and that this fright will communicate some ‘tragic revelation of truth.’ Giuliana’s problem is not just that she cannot take refuge in this old world because it is disappearing. If that were the point of this scene, the film could have portrayed the setting as a warm, comforting place, a fast-disappearing relic of the good old days when people were friendlier and the air was cleaner. What we see in the encounter with the fruit-seller is that the old world itself rejects Giuliana, finds her intrusive and out of place, and is altogether just as cold and alienating as the ultra-modern present.

This revelation is captured by the transition from the scowling fruit-seller to the wide shot of the empty street. As Giuliana looks from the one to the other, both objects of her gaze seem to say, ‘What do you expect from us?’, and both present themselves in as chilling a light as possible, with an almost cruel dramatic relish. The fruit-seller refuses to connect. The street is just as tight-lipped and inscrutable. Neither will disclose information about what they contain, what they are doing, or where they are going. Like Clara in La signora senza camelie, Giuliana was drawn to this desert space in the hope of finding some kind of mutual understanding, but instead she finds herself staring into an abyss that stares back tauntingly at her.

One of the reasons Clara struggled to form connections was that she found herself caught between two worlds, unable to thrive amongst the artifice of Cinecittà, but equally unable to return to her family and her former life. Clelia in Le amiche has a similar problem when she returns to the neighbourhood she grew up in and feels alienated from it, or when she tries and fails to maintain a relationship with the working-class Carlo. That space and that social stratum remain core elements of her identity…and yet she has left them behind and can no longer connect with them. As she looks around the working-class tenement blocks, Clelia says that she remembers them being bigger, then she notices a middle-aged woman passing by and eyeing her suspiciously, a little like Tanino in Red Desert. Clelia remembers this woman being young and beautiful; it seems to her that staying in this place, rather than getting out as Clelia herself did, has caused this woman to degrade and decay.

Carlo is painfully aware of the unspoken implication. If Clelia had stayed, she might have ended up marrying him or someone like him, and he could never have given her the middle-class lifestyle she now enjoys. As he says this, he and Clelia stand in front of a dilapidated wall like the one that fills the frame at the start of the Via Alighieri sequence in Red Desert. Carlo leans miserably against the wall; Clelia stands a few feet away from it, looking awkwardly away from Carlo. He is saying that he belongs in this place, against this insurmountable wall (the blockage at the end of the road), among the people who have covered it with graffiti. Clelia cannot admit this herself, but she cannot deny it either.

These two characters were positioned in a similar way just a few minutes earlier, when Carlo was trying to persuade Clelia to look at some furniture and she instantly wrote it off as inappropriate for the high-class salon she is trying to establish. Throughout this sequence, although it is Carlo who feels rejected, the focus is on Clelia’s rueful sense of not-belonging.

Giuliana’s feeling of displacement is less easy to explain, but there is something of Clara and Clelia about her when (thanks to the absent reverse-shots of her face) she fails to make eye-contact with the fruit-seller. She looks out of place sitting next to this grey cart. The peddler seems offended by her presence. Even his Old Man Steptoe expressions and gestures seem characteristic (or even stereotypical) of a different era and social class. It is impossible to imagine Giuliana, Corrado, or Ugo making such gestures except in mockery, just as it is impossible to imagine the elegant Clelia carrying herself like the woman in the tenement block. It is also impossible to imagine Giuliana working in the Via Alighieri and serving such customers – would this old man or the cyclist or the convent-visiting woman want Giuliana’s ceramics, and would she know how to sell to these customers? Ugo was perhaps alluding to this problem when he said that Giuliana’s proposed shop was not ‘decorous’. This is an obnoxious piece of class snobbery on his part, but it calls attention to that uncomfortable divide Giuliana senses between herself and the striking workers, or between herself and Tanino.

In one of his stories, Antonioni says that his childhood was

a somewhat colorless [incolore] period in my life, except for the fact that, breaking with the norms of middle-class decorum [le regole del decoro borghese] then very much in evidence [molto sentito], I preferred to find friends among the lower classes [figli di proletari] rather than those who, like me, belonged to the bourgeoisie. Perhaps I was unconsciously making contact with the popular background of my parents, who were, let’s say, self-taught [autodidatti] bourgeois.5

The lower strata of society are associated with an earlier generation (‘children of the proletariat’); making this connection would bring colour to an otherwise colourless childhood; powerful regole del decoro militated against such connections; unconscious instincts fought against these rules; and the parents’ ascension into the middle class occurred through a process of self-teaching, a forced and non-instinctive advancement – not unlike a technological leap forward that causes drastic changes in our way of life. The passage just quoted occurs at the beginning of the story discussed in Part 12, the one that centres on a feeling of being trapped in an in-between space. An announcement declares a reunion for people born in 1882; a list of professors indicates that one of them will retire in 2006:

I suddenly felt squeezed, trapped between those two dates: 1882 and 2006. And it was then that I thought of my youth and I felt a crazy wish [voglia matta] to make a film, a film about me, that ‘third person’ me [il sottoscritto, literally ‘the undersigned’] of those years on which – rudely and perhaps unreasonably – I’d turned my back.6

An era, a class, a set of friends, indeed an entire self – that self whose signature seems like that of a stranger now – have been rudely and (perhaps) unreasonably abandoned. La signora senza camelie and Le amiche are the Antonioni films that explore this rejection most overtly in terms of class, but all these sentiments linger in the Via Alighieri sequence in Red Desert as well, especially in the confrontation with the fruit-seller. The ‘secret and reciprocal creative satisfaction,’ the ‘shared sense of the tragic revelation of truth’ that Antonioni supposedly felt when filming this sequence, are related to the feelings that made him want to direct a film about his youth, and that made him write off this idea as ‘crazy’. These feelings have to do with the passage of time, or more fundamentally with the process of change, and the losses inflicted by that process: whether because of age or progress or the unreasonable demands of propriety, things go grey and die and disappear.

Next: Part 14, Celeste e verde.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 97. Chatman and Orr (cited below) are engaging with Pasolini’s argument about Red Desert’s play with perspectives in the essay ‘Cinema of Poetry’, which I will discuss in Part 29. Paul Coates’s reading of this sequence in Cinema and Colour: The Saturated Image (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), p. 75, is also relevant here, but I will come back to this in Part 16.

Orr, John, Contemporary Cinema (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), pp. 2-3

Niccolini, Flavio, ‘Diary’ (1964), trans. Maggie Fritz-Morkin, Words Without Borders (02 March, 2011). The original Italian text is published in Michelangelo Antonioni, Il deserto rosso, ed. Carlo di Carlo (Bologna: Capelli, 1964).

Pinkus, Karen, ‘Antonioni’s Cinematic Poetics of Climate Change’, Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 254-275; p. 267

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Report about myself’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 91-96; p. 93. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Report about myself’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 105-110; p. 107.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Report about myself’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 91-96; p. 96. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Report about myself’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 105-110; p. 110.