Giuliana accompanies Corrado on his journey to recruit a worker, named Mario, for the construction project in South America. They travel first to Ferrara, where Mario lives, then to Medicina, where he currently works. In the course of this two-stage field trip, we see the relationship between Giuliana and Corrado develop in the same way that it began: ambiguously, with much attention drawn to the artificial codes and structures that shape this ‘affair’.

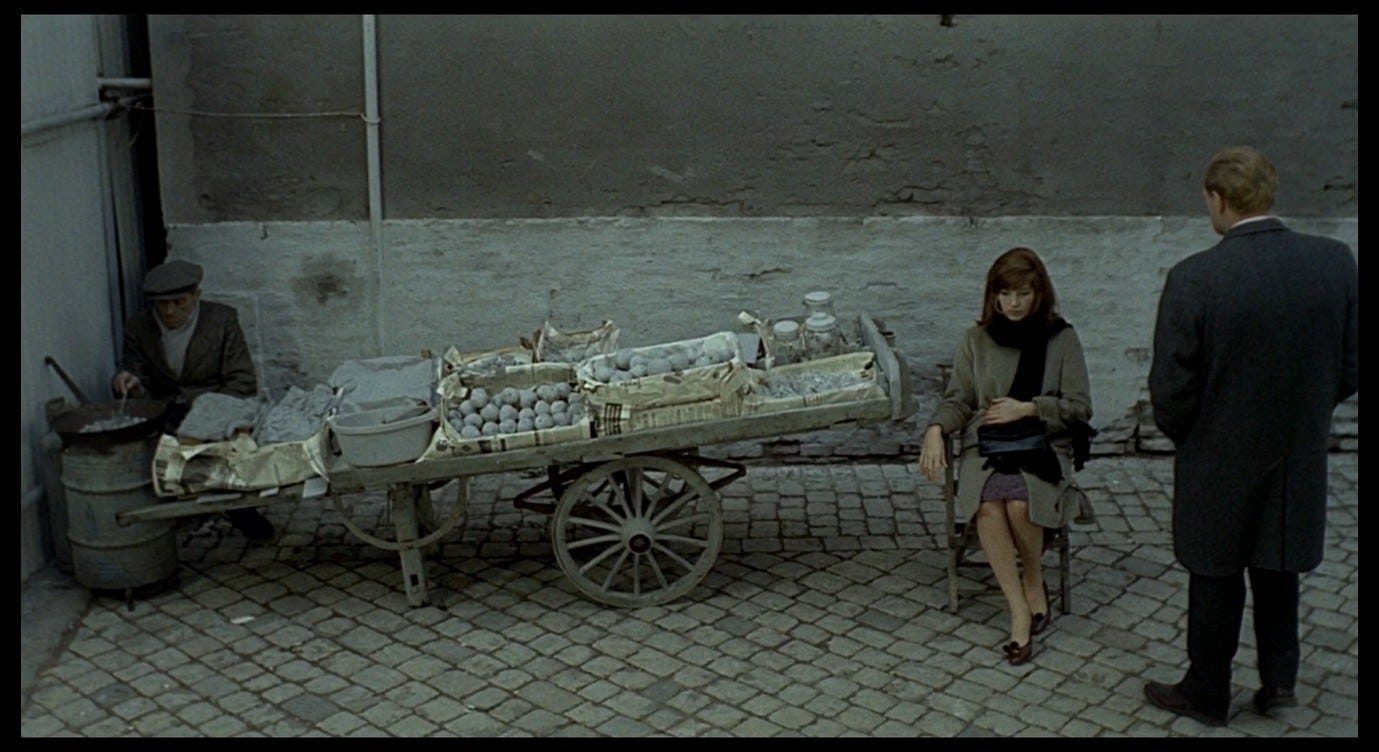

To begin with, the transition from Ravenna to Ferrara comments on the ill-defined connection between Giuliana and Corrado. At the end of the Via Alighieri sequence, the two characters leave each other on a note of uncertainty: he is travelling to Ferrara; she says she may be able to join him in the afternoon. They are standing a long way apart; he seems to want to drive her home; she wants to walk. The wide-angle lens captures the distance between them, and from Giuliana’s point of view the grey fruit-seller can still be seen in the background. From Corrado’s perspective, we watch Giuliana walk away towards that unsettling turn at the other end of the grey street. Then we cut back to the reverse-shot and there is a conspicuous empty space in the part of the frame that Giuliana had occupied.

It is a classic Antonioni moment, reminiscent of the final rift between Lorenzo and Rosetta in Le amiche, or the train departure scenes in that film and in L’avventura: brief, baseless encounters dissolving into oblivion.

For a moment, we are left with the sense that Giuliana and Corrado have failed to connect, that it is Giuliana who has chosen not to make the connection, and that there is no certainty about the future of this relationship.

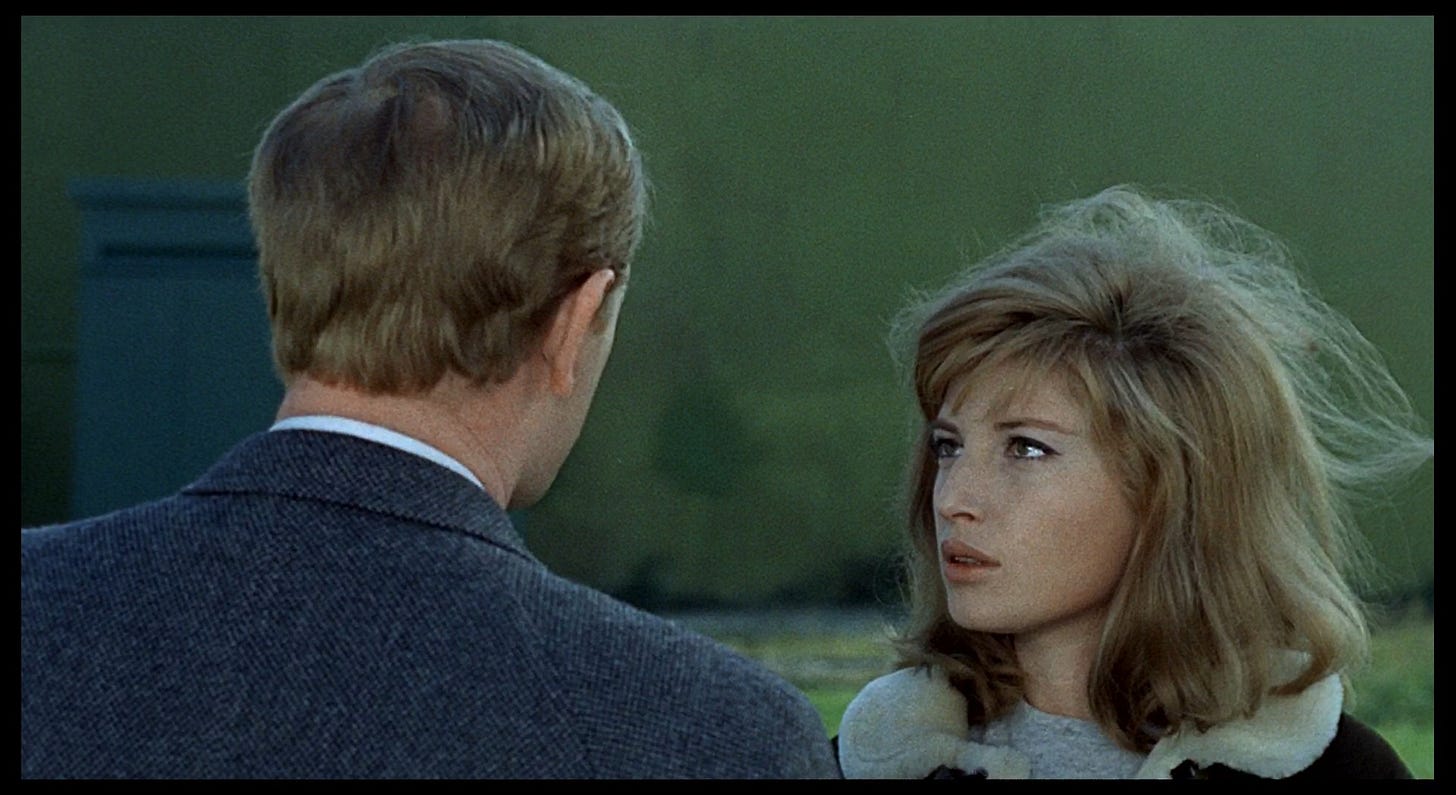

Then a jump-cut takes us to a telephoto-lens shot of the couple walking together, in Ferrara as it turns out, occupying the side of the frame left empty by Giuliana’s departure.

The long lens has removed the impression of distance and empty space, and Giuliana seems to be cheerful. The abruptness of the transition is disorienting. We would expect the film to do some work to smooth this over, perhaps using a dissolve to indicate the passage of time, perhaps showing the two characters in a car on their way to Ferrara, Giuliana’s mood improving gradually along the way. Instead, the film simply puts them together; they were separated and now suddenly they are not. Their connection seems to happen inevitably, in defiance of the choice Giuliana made in the previous scene. Within seconds she will become anxious again, and having been frightened by the escaped eel (more on this later) she will be seen running away, alone, in another disorienting switch to a wide-angle shot.

A moment later, Corrado has caught up with Giuliana and is telling her about transparent fish that live in the darkest depths of the ocean. She asks him not to talk about such things - they trigger her deepest fears.

This sequence is, in part, about the inevitability of the love affair between Giuliana and Corrado. It makes us feel that there are forces pushing these two together and that the film itself is complicit in the operation of those forces. Cinematic conventions and storytelling tropes insist that these two are falling in love; and yet, at the same time, the film undermines these clichés by showing that Giuliana is in crisis and that she wants help, not an affair.

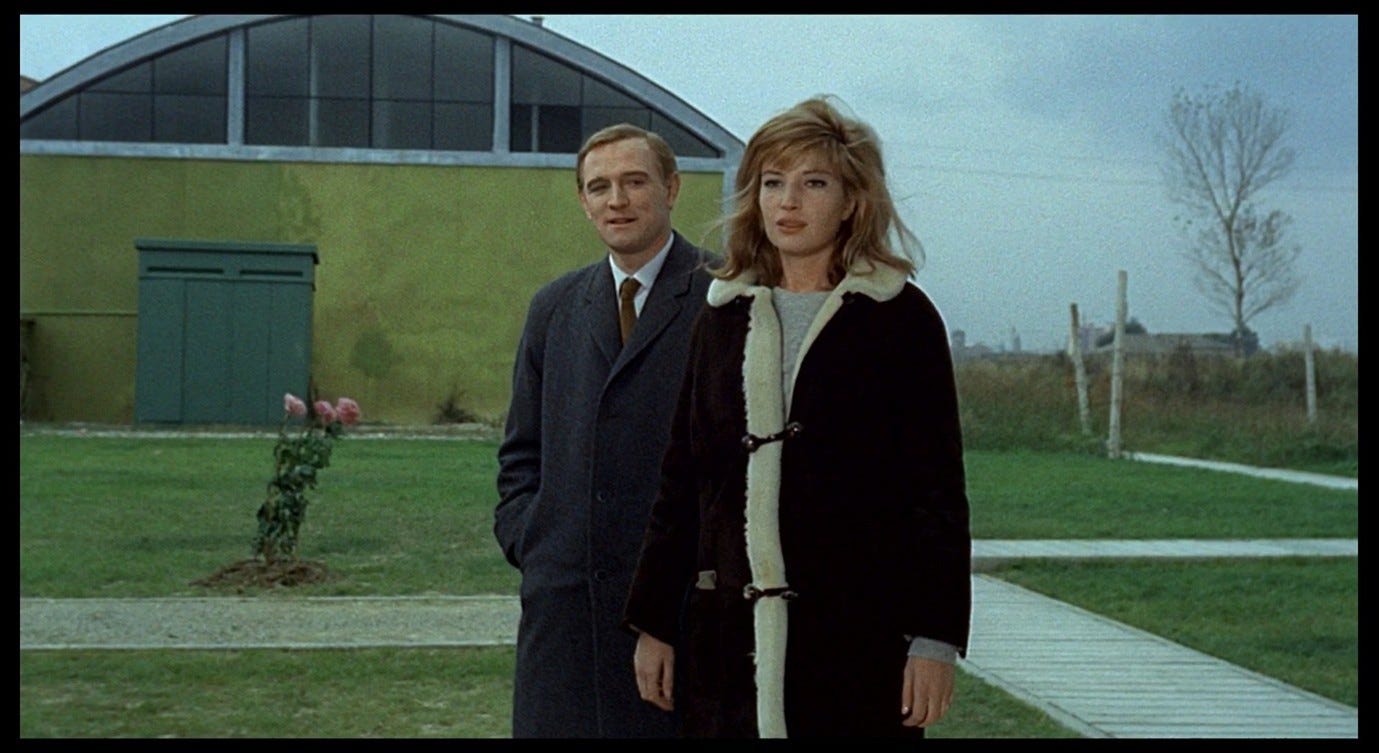

As the characters approach Mario’s apartment block, we see three pink flowers planted together in one of the communal lawns. The flowers become a weirdly persistent on-screen motif. They first appear when Corrado introduces the concept of ‘love’ into the conversation (when he asks whether one should only eat animals one loves), and after briefly disappearing behind Giuliana, they reappear during a moment of dead time at the end of the shot.

Then, as the characters enter the building, the flowers are placed in the foreground, out of focus, occupying the same part of the frame (but more of it) as they did a moment earlier.

Giuliana looks around furtively before Corrado directs her towards the building entrance. In their out-of-focus state, the flowers no longer resemble flowers, but become diffuse blobs of pink, momentarily ‘framing’ Giuliana and Corrado as they pause in the open doorway.

Once the characters are indoors, the flowers can be seen in the background.

And again, we are given a few seconds to contemplate them in the dead time at the end of the shot.

Later on, outside again, when Corrado is deciding to go to Medicina, we see the flowers for the last time, far in the background behind Giuliana.

Seymour Chatman sees Antonioni’s ‘dead times’, when we are asked to contemplate seemingly insignificant features of a setting, as subversions of the cinematic ‘establishing shot’:

What is established is not ‘the same place’ but the possibility that it is in reality ‘another place,’ perhaps even an extradiegetic place. The scene is made portentous by a delay that challenges the whole tissue of fictionality. The film says not that ‘this is such-and-such a place, in which plot event X occurs’ but rather that ‘this place is important quite independently of the immediate exigencies of plot, and you will sense (if not understand) its odd value if you scrutinize it carefully. That is why I give you time to do so.’1

‘[G]azing at something far longer than you were asked to,’ says Roland Barthes, ‘upsets the established order in whatever form, since the extent or the very duration of the gaze is normally controlled by society.’2 That societal control over the duration of the gaze is interdependent with what Chatman calls ‘the whole tissue of fictionality’ because it is integral to the effective unfolding of the story being told. ‘We are here; this happens; now we move on.’ If, instead, the story-teller says, ‘We are here; this happens; now stay here…’, then we are left with the question, ‘What is happening now?’ As Barthes says, this is dangerous because we might answer the question in any number of ways – in ways that might undermine the meaning of the plot-event we just saw.

These flowers are a functional component within the industrial landscape, much like the colour-coded pipes and works of art in the factory. The workers’ housing complex must have lawns and flower beds for the sake of the inhabitants’ wellbeing, so the company provides a small lawn with three flowers planted in it. The flowers seem comically isolated and out of place. There is something robotic about the mentality behind this landscaping choice, and about the effect it is clearly designed to have on people. The workers will not encounter flowers, or the colour pink, in the factories. The pink flowers are indicative of the mood and activities proper to a domestic space, but this gesture towards organic beauty – growing out of its sad little mound of earth – only throws into relief the cold artifice of the surroundings, especially when we take a few moments to contemplate the gesture in isolation.

Inside Mario’s apartment, the wallpaper is green with blue-stemmed, pink-petalled flowers, echoing the green/pink combination outside. The sofa-covering depicts a forest and a dark blue river with swans.

These are representations of and substitutions for things that have been eradicated, further reminders of ‘natural’ beauty that are supposed to make the space feel less de-humanising. The stage directions in the screenplay call the apartment ‘very tidy’, with furniture that is ‘tacky [di cattivo gusto].’ They also note that a series of identical buildings can be seen through the window, and then they conclude: ‘A sense of isolation, of silence.’3

This isolation seems to be caused by the surroundings. It is the relentless functionality of this world – the identical, orderly spaces designed to make you feel specific emotions – that makes it so lonely.

Murray Pomerance describes the factory complex in the early scenes of Red Desert as ‘an interlocking chain of sedate and fundamentally hygienic factory locales, managed rationally by intelligent men of expertise and grace,’4 and links this to the sense of abstraction evoked during the visit to Mario’s flat, both by Corrado’s stories of transparent fish that live deep in the ocean and by the abstracted images of pink flowers:

Abstract conversation is modern, […] implying unrelenting movement and change of scene as well as the disconnection of action and setting: that far from waters one can discuss fish. […] To speak of transparent fish while walking past a tiny implantation of roses into a cool apartment complex is the height of abstraction. Modernity, mass society, rapid mobility, and industrialism all favor the abstract relation, but Giuliana is trying hard, against considerable odds, to be here in what she thinks, what she says, and what she does, and so the ‘transparent fish’ are terrifying. Not the fish themselves but the invocation, which is itself transparent, slippery, always evading the real.5

This has an important bearing on Chatman’s reading of the ‘dead times’, which arguably reverse the disconnection of action and setting by insisting that the latter continues to exist after the former is completed. We were in Ravenna but that segment of the story is over and now, suddenly, we are in Ferrara; an eel just fell off a cart so now we are in the depths of the ocean with the transparent fish; but now we are going to remain at the foot of this stairwell and take a moment to acknowledge that every action is grounded in a particular context. Those pink flowers did not only exist during, and for the sake of, the conversation we have just seen: they were there already, and will continue to be there afterwards. This undoes their ‘abstract’ function by making it visible, by making it apparent that they were being used to invoke certain ideas or feelings. It is as though a rainstorm were being used to make a conversation seem more dramatic, but then we continued to watch the rain after the conversation fizzled out, and we realised that the rain was being made to signify something.

This is what Noa Steimatsky identifies as Antonioni’s ‘[preoccupation] with distilling cinematic form from the profilmic subject at hand,’ linked with his ‘documentary consciousness’ which ‘sharpened his sense of taking nothing for granted: nothing as settled and coded.’6 Antonioni’s dead times entail the ‘palpable withdrawal of narrative and dramatic figures and codes,’ displaying

a documentarist’s sense of the unfolding of the profilmic place in the duration of a shot, the unraveling of relationships in time and space consciously differentiated from the suggestion of cause and effect, from narrative and expository remnants.7

We saw something of this in Part 15, in the dissection of the screen-test in ‘Il provino’. That film is arguably a quasi-documentary on the re-making of Princess Soraya as an actor, with the spaces and objects in front of the camera (the ‘profilmic’) serving as both backdrops to a fiction and conspicuously ‘real’ elements that we know would exist with or without the fiction, but that are being deployed in the service of someone’s agenda. Probably not the real Soraya’s agenda, we sense, nor that of the character she is playing.

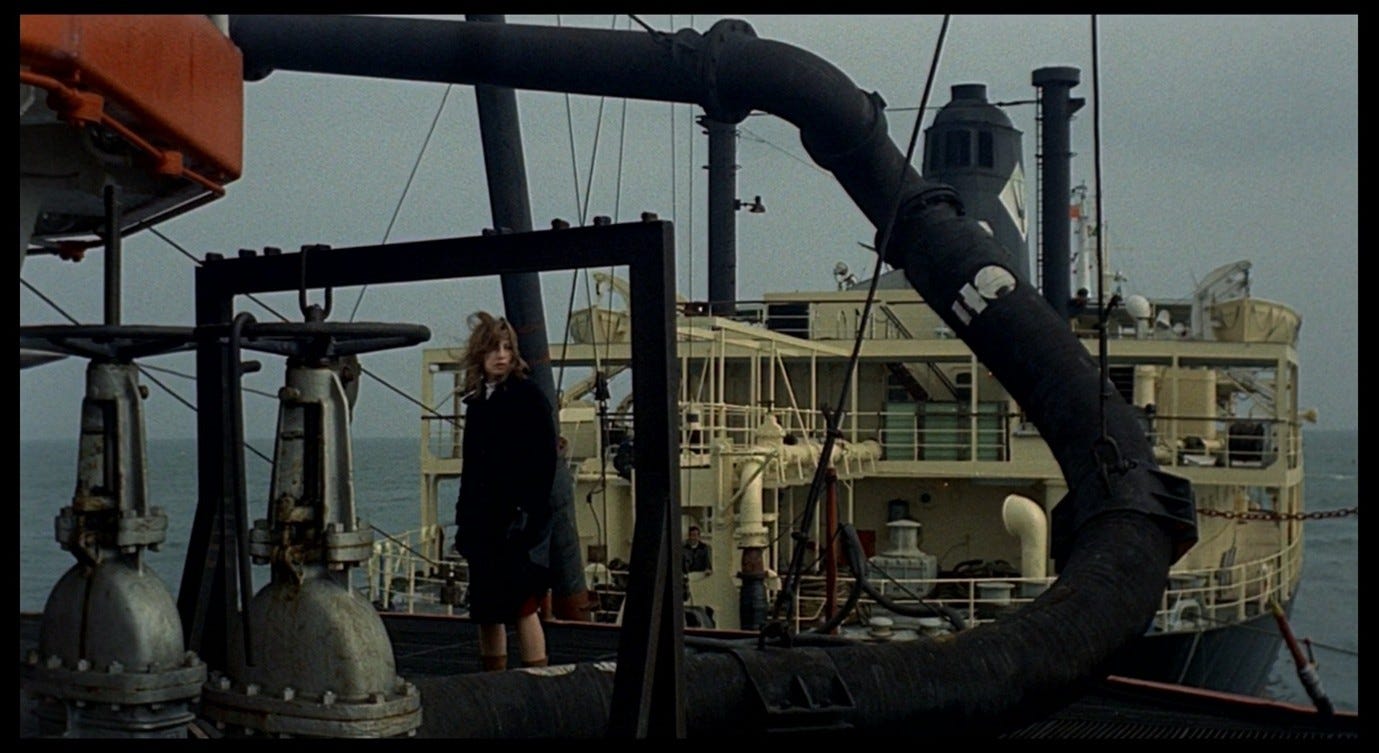

The quasi-documentary aspect of Red Desert becomes most prominent in the SAROM Island sequence, but there too the rig is filmed in a spirit of ‘taking nothing for granted.’ Like the pink flowers, the isola is not just there as a backdrop for Giuliana’s isolation, or as an abstract industrial monstrosity. It has been built, it performs a function independently of the film, and it is contingent, like the Paguro platform that blew up and became a thriving marine habitat a year after Red Desert’s release.

We are made aware of these profilmic objects’ contingency. The flowers have been planted and could be ripped out of the ground and stamped on; so we can think critically about the meanings being invested in them.

When they first appear, the pink flowers help to code the dialogue between Giuliana and Corrado as ‘flirting’. Her anxieties have been triggered by the escaped eel and Corrado’s talk of transparent fish, and he responds with a non-sequitur: ‘So in order to eat an animal, you have to like it…you have to love it [le deve piacere…lo deve amare]?’ Giuliana has not said anything about eating or not eating monstrous sea-creatures. Corrado introduces this concept so that he can joke about eating lovable little kittens – thus lightening the tone of the conversation – and ultimately so that he can ask, ‘Would you eat me?’, shifting from a humorous to an amorous tone. We see him lurking behind Giuliana, smiling as he builds up to this moment, leaning against the wall so that he can (almost) put his arm around her.

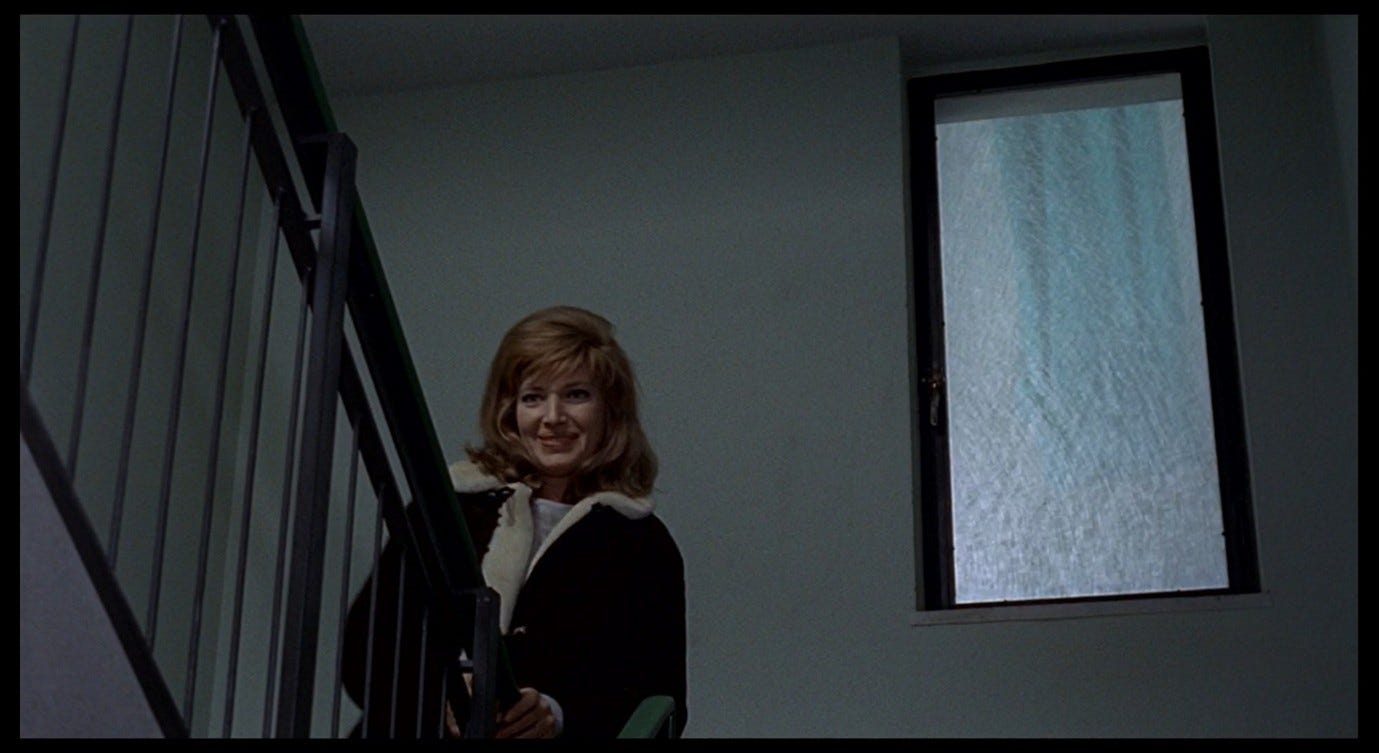

And then, once they are inside, we see him waiting for just the right moment to ask his question, when she reaches the turn of the staircase and can conveniently turn around to look down at him – she is positioned as the elevated object of desire responding to her suitor.

Corrado controls the language of this exchange, both verbally and bodily, bending a conversation about deep-seated fears into an excuse for a chat-up line. His deployment of cute animals in this conversation is, to borrow a phrase from the screenplay, di cattivo gusto. Like the other flowery components in the sequence, his conversation is tacky because it is so baldly manipulative, so forced and obvious, and so coercive. It makes me think of Angelo Restivo’s comment about the tacky commodities that are blown up at the end of Zabriskie Point:

an orgy of exploding consumer goods, among the airborne debris a loaf of Wonder Bread, which was then a staple of ordinary American households, its television commercials blatantly linking the family to the national future (‘Wonder Bread helps build strong bodies twelve ways’), but which must have seemed to the Italians as much a caricature of bread as the suburban housing developments were a caricature of ‘community’.8

Indeed, the place where Mario lives is like the Sunny Dunes development planned by the industrialists in Zabriskie Point, showcased in a television advert populated entirely by plastic dolls.

These are stories about happiness and community, constructed narratives in which we build ideal homes for ideal families. The blowing-up of the millionaire’s mansion and his fridge and his Wonder Bread is a story too, told in Daria’s mind as a protest against the more dominant narrative, before she drives off into the sunset – perhaps unable to escape the traditional codes and clichés of a Hollywood movie.

Corrado too is telling an inescapable story, one in which every conversation – even one about eels – will inevitably end in ‘I love you.’

However, Giuliana’s response is knowing and ambiguous. She turns on the stairs, apparently caught off guard. It takes her a moment to register what Corrado has done and to formulate an answer. To the question, ‘Would you eat me?’, framed as Corrado has framed it, she cannot say ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ without either declaring her love for him or causing offence to her new friend. But then she smiles and says, ‘If I loved you [Se ti amassi],’ before laughing and ascending the staircase. The screenplay notes a crucial but un-translatable feature of this exchange when it comments on Corrado’s reaction: ‘He is struck by the change to “tu”, so sudden and unjustified, and he becomes serious [serio].’9 In the scene as filmed, he certainly appears taken aback, but not necessarily serious; he laughs along with Giuliana as he follows her up the stairs.

The response, ‘If I loved you’, conveys a number of things. First of all, Giuliana is showing that she understands Corrado’s trick: it is as if she were saying, ‘I see what you’ve done, and I’m not falling for it.’ She softens this comeback by laughing, framing it as witty repartee rather than a severe rebuke. At the same time, she switches to the familiar ‘tu’, affirming a level of intimacy that surprises even Corrado. This pronoun shift constitutes a kind of answer to the implicit question, ‘Does Giuliana love Corrado?’ To call him ‘tu’ means that she regards him as some kind of ‘amico’, someone she likes well, but it does not clarify whether he is a friend or a lover.

In the screenplay, it is also not clear why Corrado is said to become ‘serious’. Was his pick-up line only intended as a joke, and does he take her response (specifically the shift to ‘tu’) as an invitation to make it real? Or is he shocked to discover that she regards him as a close friend, and that her confidences (which he has made light of) are an earnest cry for help? These ambiguities are retained in the finished film, but Corrado’s laughter (which is not in the screenplay) suggests that he leans towards the more self-interested interpretation of Giuliana’s comeback – the one that validates his attempt at love-making. He seems delighted by the flirtation, by the way she ‘plays hard to get’ while still encouraging intimacy.

In their first few appearances, the pink flowers signal the tone of this scene, or rather, they impose a tone and a meaning on it. Their colour bears a relationship to the pink (rosa) of the beach in Giuliana’s story later in the film, and to the pink that pervades Corrado’s hotel room shortly after that. William Arrowsmith argues that these motifs accumulate as the film goes on: the ‘note of romantic anticipation’ when Giuliana and Corrado go their separate ways in the Via Alighieri is taken a step further by the ‘pink carnation in soft focus,’ which represents ‘the incipient love we see blooming’ between these two characters; the pink rocks in the island fantasy constitute a kind of erotic ‘epiphany’ in dream-form; and at the end there is an ‘actualization in the bedroom of the erotic suggestions so vivid in the Sardinian beach fantasy.’10 Arrowsmith’s reading of these motifs is not simplistic or un-critical, but it focuses on the most conventional coding of such motifs. That note of romantic anticipation, that incipient love, and those erotic suggestions are all questionable; they could all be read as something else. As Arrowsmith himself says in his piece on L’avventura:

incipient individuality (those Antonioni ‘loners’ always, at great cost and with great difficulty, detaching themselves from the group) is difficult precisely because the world is organized to suppress individuality, to coerce each person back into the Game. […] The group is powerful against the individual precisely because it is the group, because it can suggest that the failure to conform to its norms is illness, neurosis, even madness.11

Giuliana’s ‘madness’ will be manifested, in part, by her resistance to the affair with Corrado, and by her negative reaction to its consummation. The intimations of romance scattered through the film, especially those associated with the colour pink, are like sign-posts Giuliana is supposed to follow. She fails to follow them, insistently seeing something else in their place.

Peter Brunette sees Giuliana’s ‘mental illness’ as ‘only a more serious version of that reluctance to accept a predetermined female subjectivity […] that we saw in [Antonioni’s] earlier female protagonists.’12 He relates this especially to Giuliana’s role as a wife and mother, but the point applies just as much to her relationship with Corrado. In this light, it is worth noting that the ‘if I loved you’ exchange appears in a very similar form in one of Antonioni’s short stories, and in a story whose subtext is a conflict over pre-determined gender roles. Aldo and Ivana, a formerly engaged couple, argue about a business deal that Aldo is in the process of completing. The deal will destroy the Ravenna pine forests in the name of vague concepts like ‘il progresso, la socialità,’13 which Aldo invokes weakly. Ivana interrogates him about his true feelings on this subject, and concludes, ‘You see, it makes no sense. [Vedi che non ha senso?]’14 Aldo changes the subject to food, and then they argue about Ivana’s refusal to eat certain types of bird. ‘All women are the same,’ says Aldo, ‘Pity and tenderness for the poor little birdies, not for the poor baby cows.’15 But Ivana corrects him: it is not that she pities these birds, but that she dislikes them: ‘They frighten me, they horrify me.’ Like Corrado, Aldo proposes lovable kittens as a food-source; unlike Giuliana, Ivana affirms that she would eat kittens. When Aldo then asks if she would eat him, ‘Ivana turns to him with a quiet open smile [con un quieto franco sorriso]: “If I loved you, Aldo.”’16 This is how the story ends.

Ivana is an important analogue for Giuliana, though she is noticeably more confident. The story, called ‘A film to be made (or not made)’, is about a couple talking-and-not-talking about their failed relationship, and the miscommunications between them are rooted in their understanding of words like senso and amore – the meanings and emotions that motivate them. Aldo destroys things that he loves for the sake of causes he does not really care about; Ivana can only eat animals she loves. She does not love Aldo, in part because of his exploitative business practices, but more because of his lack of self-awareness, which is in turn linked to his failure to understand Ivana. In the description of her smile at the end, Arrowsmith translates franco as ‘open’, but that could suggest she is open to re-kindling her relationship with Aldo, which she is not. I think she displays, instead, a quiet frankness about her lack of feeling for him, tempered by a smile that says, ‘We are incompatible and it is better that we stay apart.’ Unlike in Red Desert, there is no shift to the ‘tu’ pronoun, and thus no sense of increasing intimacy – the intimacy of these two is all in the past – but Ivana’s frankness and humour resemble Giuliana’s. They are a way of stepping back from the clichés and codes that haunt the conversation. Yes, Aldo’s business practices are normal, but doesn’t he see how senseless they are? Yes, his misogyny reflects conventional wisdom about women’s irrational sympathy for cute animals, but doesn’t he see that Ivana is saying something different? And yes, these two were engaged and it would be the ‘done thing’ for them to get married, but doesn’t he see that there is no real love between them?

Ivana’s un-answered, conversation-killing question, ‘Vedi che non ha senso?’, is baked into Giuliana’s perspective on the world, especially in her attitude towards Corrado. As Paul Coates argues, her perspective cannot easily be written off as a reality-distorting one; it is also a commentary on the distorted reality she finds herself in, which others cannot always see or acknowledge. Coates connects the pink flowers outside Mario’s apartment to the grey fruit in the Via Alighieri, beginning with the out-of-focus image of the fruit-cart (discussed in Part 13):

Its momentary loss of focus could be taken as an expressionistic manifestation of either [Giuliana’s] neurosis, her weariness, or both. However, shots not linked to her point of view – from in front of the barrow – also display grey fruit. The fruit is grey all the time, not just when seen by Giuliana. The film oscillates in and out of an expressionistic motivation of its shifts of focus. Another focus shift occurs a few minutes later, as Giuliana and Corrado visit the home of a worker Corrado is seeking to recruit to travel to Patagonia, but without any hint of a subjective anchoring. Three flowers they have left behind appear out of focus, as three blobs of pink: the shift separates colour from object in a manner that can seem simply reflective of Antonioni’s fascination by formal methods for highlighting colour, but which also reiterates the concern with the blurring of boundaries, as the flowers, shot thus, lose their clarity of outline.17

Red Desert works to question the distinction between subjective and objective images, between visual distortions that reflect a character’s ‘mistaken’ perspective and those that exist independently of that character. Giuliana is not looking at the flowers when they appear out of focus, when they stain everything with pink, and yet the image is undeniably distorted. If anything, that (singular) pervasive pink blob and the (plural) flowers it no longer resembles are invested with a kind of dramatic irony, as though we were seeing an expressionistic manifestation of something that Giuliana herself is, for the moment, oblivious to. The fruit in the Via Alighieri is not fruit, it is grey – the concept of greyness – to embody Giuliana’s depression. And yet, it is also grey for reasons that transcend her depression, that comment on the world she lives in. These flowers are not flowers, they are pink – the concept of pinkness – to embody a more nebulous set of meanings associated with the developing affair. As such, they are more obviously located outside Giuliana’s mind, less anchored in her subjectivity; they are a manifestation of those ‘vieilles choses’ which Antonioni described as the source of her problems (see Part 9).18

The blurring of boundaries, the separation of colour from object, and the exposure of the codes behind these facets of ‘reality’ are framed in another way by Roland Barthes, who argues that in Red Desert ‘affection [les affects] – or rather a malaise of affection [le malaise des affects] – escapes the armature of meaning that constitutes the code of passions [le code des passions].’19 Artists like Antonioni, he says, possess an ‘acuity of discernment which permits them never to confuse meaning [le sens] with truth [la vérité]’:

He, the artist, knows that the meaning of a thing is not its truth; this knowledge is a wisdom, a foolish wisdom, one might say, because it removes him from the community [la communauté] [but also] from the company of the arrogant and the fanatic. […] [Y]ou [Antonioni] exhibit a just feeling for meaning: you don’t impose it, but you don’t deny it either. […] [Y]our art consists in always leaving the road to meaning [la route du sens] open and as if undecided – out of scruple. […] This escape from meaning, which does not imply its denial, allows you to undermine the psychological fixtures of realism. […] I think of Matisse […] [painting] the representable object in that rare moment in which the whole of its identity falls brusquely into a new space – that of the Interstice.20

When Ivana says to Aldo, ‘Vedi che non ha senso?’, she is rejecting the socialità he invoked as a justification for his exploitative business deal. She thus displays that wisdom which Barthes says alienates one from la communauté. It is easy to see what he means, because deconstructing the sense(s) of every action and utterance also calls into question the bonds that a community or society relies on. And yet Barthes sees this ‘acuity of discernment’ as urgently needed, because it draws attention to emotions – to elements of subjective experience – that socialità and the communauté would stifle.

Much of what we see in the interactions between Giuliana and Corrado is pregnant with meaning, but also with sens in the sense of ‘feeling’. Barthes is not setting truth in opposition to falsehood, but protesting against the monolithic truth that imposes a single meaning or emotion on (in this case) a work of visual art, or that insists on a ‘code of passions’ from which characters cannot deviate. One meaning of the pink flowers, and of the seemingly coded exchanges between Giuliana and Corrado, is the ‘incipient love’ that Arrowsmith sees blooming, that ‘note of romantic anticipation’ as Giuliana walks away from Corrado and he watches her go. But as Barthes says, Antonioni leaves the route du sens – the road to or of meaning/feeling – open, ‘out of scruple.’

That last phrase reminds me of Antonioni’s story about the woman who murdered her father by stabbing him twelve times. Twelve stabs, Antonioni feels, ‘were much more familiar, more domestic [molto piú familiari] than two or three.’21 He ends the story on a note of un-spoken, un-recreated affects, to use Barthes’ word:

I was tired and irritated. As though I had just finished shooting the scene of the knifing and, instead of twelve blows, I’d decided that three were enough. Out of prudence [Per discrezione].22

Arrowsmith translates the single word ‘familiari’ into two words: twelve stabs are not just more familiar but more domestic. This strengthens the idea that the woman’s act of violence against her father was rooted in a familial, intimate, private space; this was domestic violence, situated in a relationship that was not visible or legible to outsiders. If she had simply wanted to kill her father she would have stabbed him two or three times, but twelve stabs suggest an intensity of emotion that frightens Antonioni. Contradicting Barthes’ tribute, he would have to close down the route du sens in this case, discreetly removing a layer of feeling. Arrowsmith translates discrezione as ‘prudence’, which I think implies a concern for the film-maker’s own reputation, his anxiety as to how the audience might react. ‘Discretion’ connotes something subtly different – a concern for the woman herself, a desire to conceal something unspeakable in her story that she would not want exposed. Antonioni is irritated and exhausted by the need for such discretion, or by the repressive forces behind it. In writing the story, in referring to this discretion, he is also subverting it, inviting us to go down that route du sens ourselves after the story is over, to consider what malaise des affects might lie behind the woman’s actions. In Red Desert, we understand the conventional sens behind the pink flowers, but we also feel how oppressive that sens is and detect a more open, complex set of feelings behind Giuliana’s responses to Corrado.

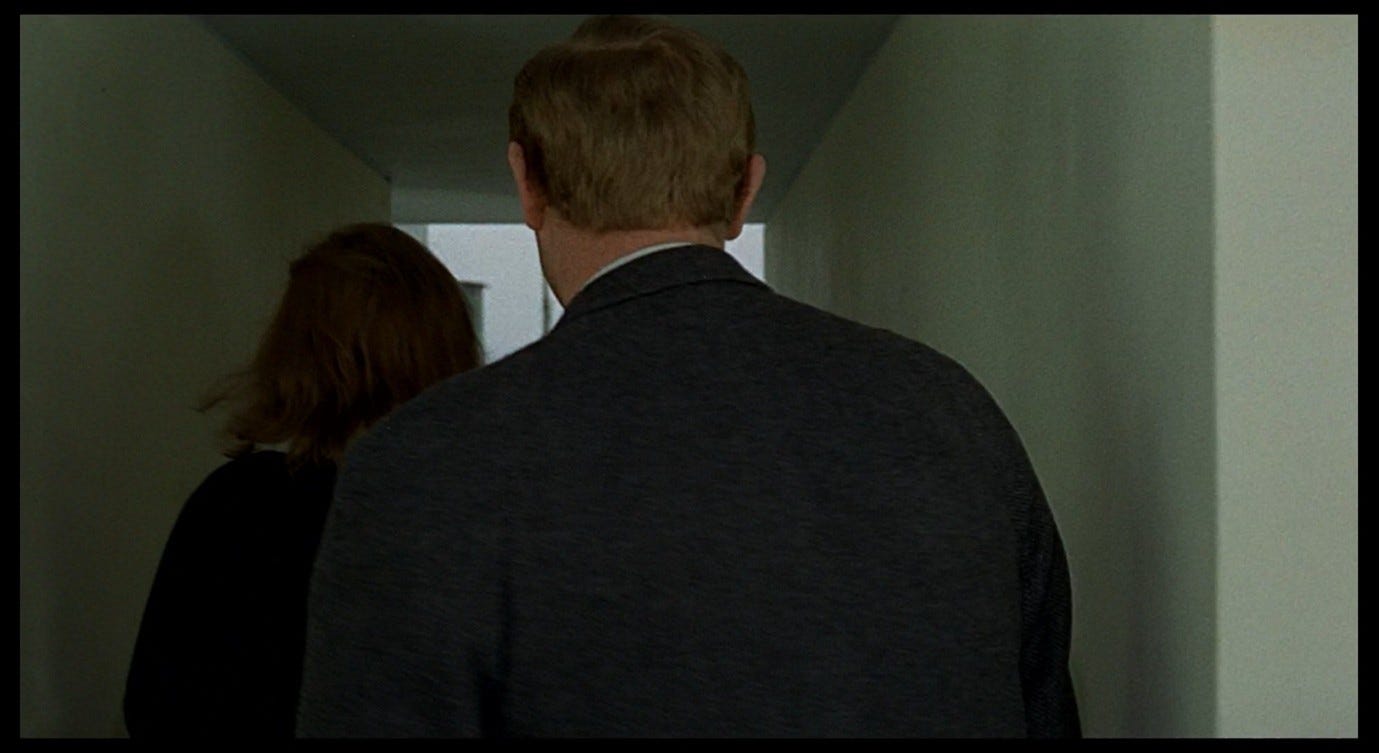

The isolation of the pink flowers when we first see them, their disconcerting effect when they are smudged across the screen, and the deliberateness with which they are kept in sight after Corrado goes up the stairs, all serve to lend a coercive feel to this tonal sign-post. This air of coercion also hangs over Corrado’s work project: he is not only hunting Giuliana, he is hunting workers for the Patagonia enterprise (Ugo warned him away from the ‘game reserve [riserva di caccia]’ in which his own employees work), and in the present sequence he is bent on recruiting Mario. The final appearance of the pink flowers comes after the visit to Mario’s wife: she has made it clear that she does not want her husband to travel abroad, but Corrado proudly tells Giuliana that he will track Mario down in Medicina: ‘You’ll see that he won’t say no.’ The pink flowers are noticeable in the background as Giuliana stares at Corrado. The screenplay states that she is ‘so taken aback by his insensitivity that she does not have the heart to contradict him.’23 As the two leave the complex, they are framed from behind in a wide-angle shot that emphasises the space between and around them, in contrast to the more intimate long-lens shot at the start of the scene. Everywhere we look, there are bare, thin tree-trunks, growing out of sad little mounds like the flowers were, held stable by metal wires staked into the ground.

The parallel between Mario (who will not say no) and Giuliana (who cannot contradict Corrado) is clear, and the presence of the flowers, lurking behind Giuliana, reminds us of the ‘If I loved you’ exchange from a few minutes earlier (when Giuliana was asked a question to which she could not say no). There is an association between the workings of industry – which have imposed on these living spaces, and which are now threatening to impose on Mario – and the workings of amore.

Giuliana’s identification with Mario will be further cemented in the Medicina sequence, in two key moments: when she faces Mario and realises he was in the clinic with her, and when Corrado fails to recruit Mario and she is openly delighted.

Corrado reports that Mario has ‘laughed at’ the generous offer of work, and Giuliana laughs too. The film leaves out a detail from the screenplay, which states that Corrado laughs, ‘but a little unwillingly.’24 These two motifs, of Corrado laughing in response to Giuliana’s laughter, and of imposing on someone against their will, again recall the flirtation in the Ferrara sequence.

It is interesting, however, that the change from screenplay to film is inverted on this occasion. Before, Corrado’s ‘seriousness’ in the screenplay turned into laughter in the finished film; this time, his laughter in the screenplay is removed in the finished film, while Giuliana laughs alone. It is not clear whether he even notices her teasing response to his bad news, ‘Cosa?’ (meaning something like ‘You don’t say?’). We already know that Corrado is frustrated in his work and frustrated by the challenges of this recruitment drive. The sour note at the end of the Medicina sequence, which merges into Corrado’s morose contemplation of the polluted swamp at the start of the next sequence, reminds us that we are watching a familiar Antonioni ‘type’, the man whose desires are fuelled by resentment. Gabriele Ferzetti played the two most memorable examples, as the failed artist and architect in Le amiche and L’avventura respectively, picking fights and bedding women in the hope of re-asserting his potency.

Corrado, of course, is more subdued than the Ferzetti characters, but there is an important overlap between his pursuit of Giuliana and Lorenzo’s/Sandro’s womanising behaviour in those earlier films.

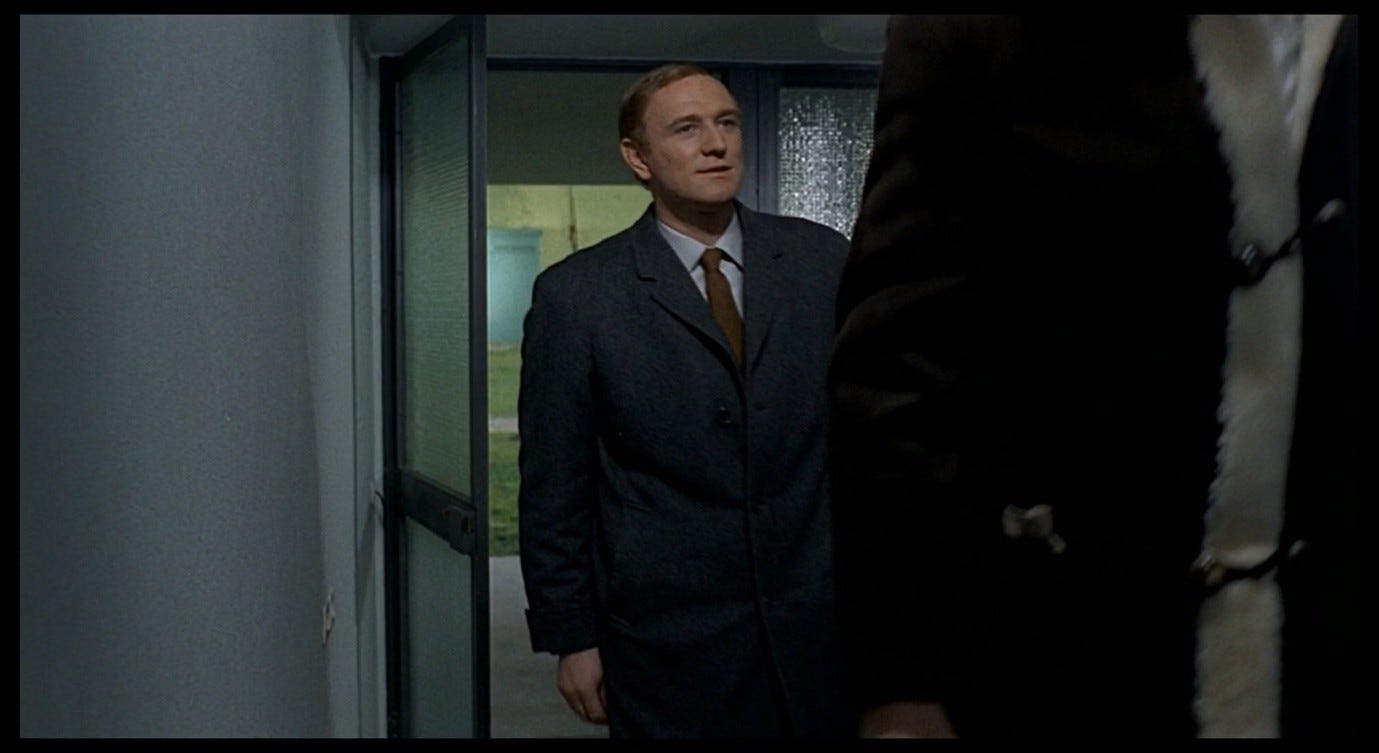

When Corrado tells Mario’s wife that she could eventually join her husband in South America, she asks, ‘Is your wife going with you?’, and turns to look at Giuliana.

It is a familiar ‘adultery drama’ moment, of the kind that would normally be followed by reaction shots conveying the characters’ embarrassment, guilt, or amusement. But the reaction shots are conspicuously absent here – the film simply cuts to Giuliana and Corrado outside.

We are alerted to the trajectory this story will follow, but in a way that leaves us unsure of the characters’ feelings and equally unsure of how we should respond. These two have put themselves in a situation where they are mistaken for a romantic couple, but this only tells us about other people’s preconceptions, not about the reality of what is happening between Giuliana and Corrado.

We are used to picking up on storytelling cues to infer that fictional characters are in love. As a general rule, a man and a woman are not put together like this, and are not seen talking like this, and are not mistaken for husband and wife like this, unless we are meant to think they are falling in love. But in Red Desert, the hints of artificiality and coercion in the onset of the affair, and the missing reaction shot after ‘Is your wife going with you?’, invite us to reflect on the assumptions at work, within the film and within our own minds. Giuliana will, as she says at the end of the film, ‘succeed in becoming an unfaithful wife,’ but the relation between her story and the adultery dramas she finds herself emulating will be a complex one.

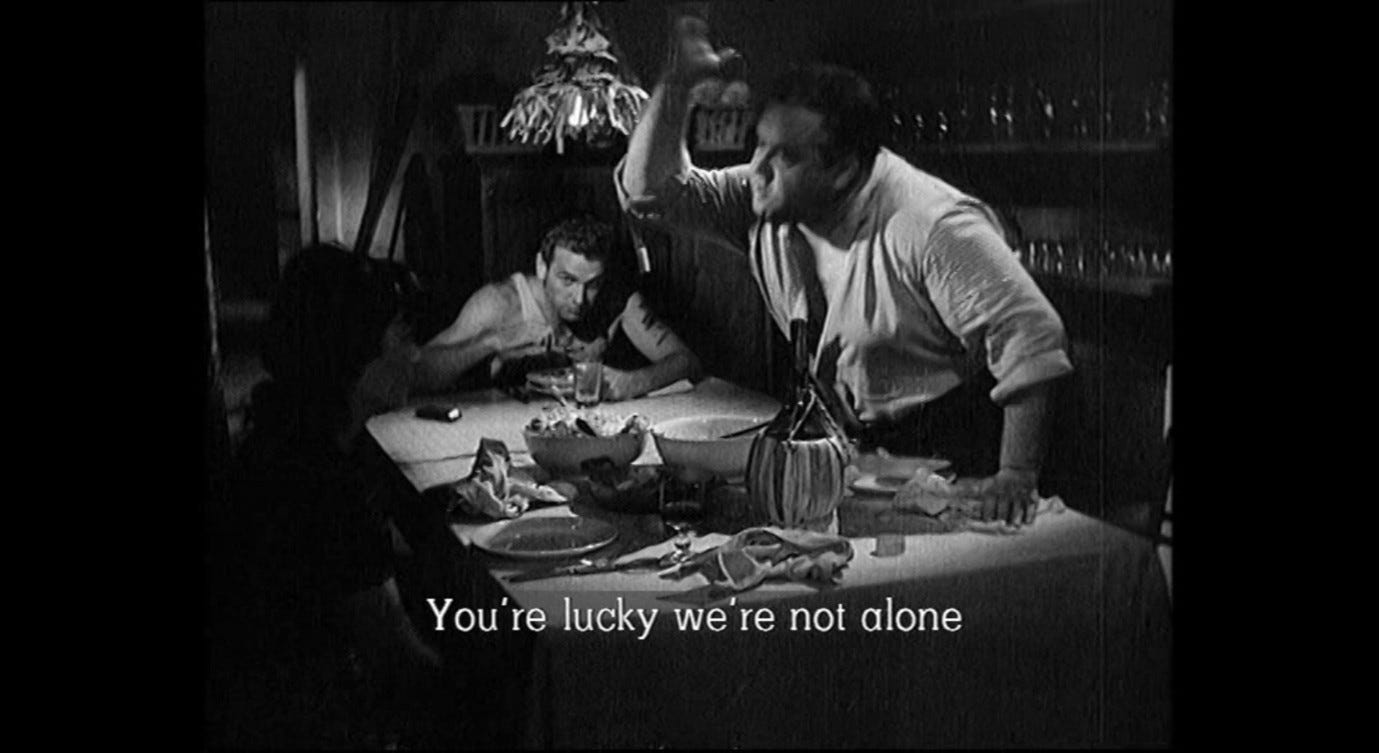

Antonioni’s first feature film, Story of a Love Affair, was a response to the noir template set by James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, and more specifically a response to Ossessione, Luchino Visconti’s unauthorised adaptation of that novel. Antonioni’s film cast the lead from Ossessione, Massimo Girotti, in a similar role as the down-at-heel drifter in love with a married woman, helping her to murder her husband. In both films the husband is possessive but unloving, suspicious but oblivious, and his wife, feeling trapped, has reached the breaking point. When a younger man materialises in her life, she sees a chance for escape. As the illicit couple plot the husband’s death, tensions grow between them, and their crime ultimately tears them apart in one way or another.

An exchange from Double Indemnity sums up the typical balance of culpability in these stories: when Phyllis says, ‘We’re both rotten,’ Walter replies, ‘Yeah, only you’re a little more rotten.’ In the Visconti and Antonioni films, Gino and Guido are, on one level, hapless innocents who lose their way because they fall for the wrong woman; and Giovanna and Paola are, on one level, femmes fatales whose selfish urges lure men to their doom. It is important to emphasise the phrase ‘on one level,’ because these films are not just misogynistic cautionary tales. However, Story of a Love Affair suffers from the fact that it has less sympathy for Paola than any subsequent Antonioni films have for their female protagonists.

Two of the key differences between Ossessione and Story of a Love Affair have to do with the nature of the wife’s unhappiness and the nature of the ‘escape’ offered by her lover. Giovanna, in the earlier film, lives in squalor with her sweaty, brutish husband.

She is loath to give up her (minimal) financial security to run away with the vagabond Gino, but he is irresistibly handsome and virile: the film makes much of Girotti’s semi-naked (and extremely hairy) body.

Pasolini would showcase this (still extremely hairy) body 26 years later in Theorem, which ends with Girotti wandering naked into a desert and letting out a primal scream.

In Story of a Love Affair, Antonioni does the opposite: he covers Girotti up and muffles his erotic appeal. Both the squalor of the earlier film and the repulsiveness of the husband have been put aside. Paola lives in luxury and Guido is poor but not destitute. He angrily declares himself ‘Uno spostato senza una lira,’ literally a penniless displaced man (or misfit), but this means he is scraping by and has no status amid the relative prosperity of Italy in 1950, not that he is literally unhoused and starving like Gino. Even more importantly, Guido is not a stranger who happens to be passing through, but a lover from Paola’s past who seeks her out.

In Ossessione, Gino and Giovanna are drawn to each other by primal lust. She has been starved of every material pleasure for a long time, and this supremely potent vagabond, with his full chest of hair, can at last give her what she needs. In Story of a Love Affair, Paola’s wealthy lifestyle begets a different kind of dissatisfaction, characterised by satiety rather than deprivation. Her husband is figured as impotent and boring rather than coarse and disgusting.

While carnal pleasure is a part of what drives Paola’s affair with Guido, he also represents something more. Paola and Guido were in love years earlier, while he was with another woman, and their affair ended after they watched this other woman fall down an elevator shaft to her death. Their semi-intentional failure to prevent this accident constitutes an ambiguous form of murder, and this is mirrored at the end of the film when the planned murder of Paola’s husband is pre-empted by a fatal accident. In the past and in the present, the quasi-killing causes the separation of the two lovers.

The film noir crime story is thus transformed, by Antonioni, into something more elusive and philosophical. Paola’s unhappiness is always defined by negation: a love affair that should have happened but did not, another woman who was not quite murdered, a hollow marriage, and now a love affair that survives only as long as it is prevented. Fittingly, her story ends with Guido telling her he will stay but then leaving.

Ossessione is about trying to fulfil primal desires in a world ruled by oppressive conventions. The lovers are ultimately defeated by those conventions, in the form of both conscience and the law. In Story of a Love Affair, the lovers do not exactly kill anyone and the authorities do not exactly catch up with them, but the existential void does.25 Now the drama revolves less around the tension between desire and the law and more around a series of questions. What is the nature of this relationship? What assumptions are being made about the eponymous amore? Does it dissolve at the end because it is only a cronaca of love, a story constituted by outdated tropes that are running out of steam – like a remake of Bicycle Thieves where the bicycle is never actually stolen, but Antonio is too consumed by ennui to make use of it?

Antonioni’s comments on the ‘problem of the bicycle’ are relevant here:

The Bicycle Thief, for example, where the main character was a laborer who lost his job because someone had stolen his bicycle, and whose every motivation stemmed from that specific fact, and that fact alone […] – this, I say, was the type of film necessary and appropriate for its time. […] It really wasn’t necessary to know the protagonist’s inner thoughts, his personality, or the intimate relationship between him and his wife; all this could very well be ignored. The important thing was to establish his relationship with society. […] However, when I started making films, things were somewhat different. […] [I]t was no longer so important […] to examine the relationship between the individual and his environment, as it was to examine the individual himself, to look inside the individual and see, after all he had been through (the war, the immediate postwar situation, all the events that were currently taking place and which were of sufficient gravity to leave their mark upon society and the individual) – out of all this, to see what remained inside the individual. […] And so I began with Story of a Love Affair.26

For me, the most interesting part of this statement is that it describes not only a break but also a continuity with neorealist concerns. Although Antonioni says that he was no longer so focused on ‘the relationship between the individual and his environment,’ that relationship is still at the core of his approach to the individual’s inner life. Bicycle Thieves is about Antonio’s place in the community: it begins by singling him out from the crowd and ends by showing him re-absorbed into that crowd.

In between, the film explores the material relations between Antonio and other people, the tension between the urge to ‘look out for number one’ and the sense that we are all dependent on and responsible for each other. If Antonioni were telling this story a few years later, he would still show these material relations, but Antonio would not lose his bicycle and we would not be rooting for him to become more aware of and connected to the human support structures around him. Instead, we would slowly explore his psychological and emotional make-up, and we would understand how his inner life had been shaped by his environment and experiences. He would be alone at the beginning and alone at the end.

If Story of a Love Affair is a familiar ‘adultery thriller’ with a twist, Red Desert is the same thing twisted almost beyond recognition, set in a time when economic stability has blossomed into the so-called economic miracle. The unhappy wife who lived in squalor with a brute, then in luxury with a bore, now lives in sterility with a robot. Her desire for physical pleasure, which became a desire for emotional fulfilment, has morphed again into something even less tangible, a desire for some kind – any kind – of connection with reality. And the sexy vagabond, who became the less sexy under-achiever, has become Corrado Zeller.

Corrado is an interesting variation on this type. Like Massimo Girotti, Richard Harris was best known for a performance that insistently emphasised his physicality. As A. H. Weiler said in his contemporary review of This Sporting Life:

[Harris] is a realistically rugged rugby player. The prognathous jaw, the overhanging brow, the dented Roman nose, piercing eyes and massively muscled torso are reminiscent of the early Marion Brando.27

The allusion to Brando’s most famous role, as a brawny, torn-vested rapist in A Streetcar Named Desire, is apt. As he did with Girotti 14 years earlier, Antonioni covers Harris up and stifles his virility, with the result that this ‘other man’ takes on an ambivalent status. On the one hand, he is more of an object of desire than the wiry, cold-blooded Ugo; on the other hand, he is never quite permitted to show why he is desirable. Insofar as we sense that Giuliana is attracted to Corrado, this sense is largely informed by our familiarity with this kind of story, and by our familiarity with Harris’s ‘massively muscled’ body – that is, by things that precede Red Desert and are inadvertently alluded to, not directly manifested. As the film proceeds, we will see Corrado pushing at the boundaries of Giuliana’s marriage, trying to edge Ugo out, but there is no question of murdering Ugo. Not unlike in Story of a Love Affair, though even less dramatically, the husband will simply disappear. Corrado is not allowed to get his shirt off (until the blurred-out hotel room scene), he cannot kill his inferior rival, and he cannot even pull off flirtation without being subverted.

Corrado’s (and Harris’s) frustrations notwithstanding, this story will (in a limited sense) go the way he wants it to. Red Desert refuses to accept narrative tropes uncritically – it does not mistake these ‘meanings’ for ‘truths’ – but crucially it also figures them as inescapable, just as, in a later scene, it will figure Giuliana as ‘incurable’. The doom that awaits all film noir protagonists, in the form of death or imprisonment, took a more purely existential form in Story of a Love Affair. In Red Desert, the equivalent of that film noir doom is the disintegration of Giuliana’s mental health. Its causes are the economic, cultural, and narrative structures in which she is trapped.

Next week: Part 17, Giuliana’s illness.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), pp. 125-126

Barthes, Roland, ‘Dear Antonioni…’, trans. Nora Hoppe, in L’avventura, ed. Seymour Chatman and Guido Fink (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1989), pp. 209-214; p. 212

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 449

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 82

Pomerance, Murray, Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), p. 95

Steimatsky, Noa, Italian Locations: Reinhabiting the Past in Postwar Cinema (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), p. 35

Steimatsky, Noa, Italian Locations: Reinhabiting the Past in Postwar Cinema (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), p. 38

Restivo, Angelo, ‘Revisiting Zabriskie Point’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 82-97; p. 83

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 449

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), pp. 101-102

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 33

Brunette, Peter, The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 103

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Un film da fare o da non fare’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 191-196; p. 194

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘A film to be made (or not made)’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 175-180; p. 178. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Un film da fare o da non fare’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 191-196; p. 194.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘A film to be made (or not made)’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 175-180; p. 179

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘A film to be made (or not made)’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 175-180; p. 179. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Un film da fare o da non fare’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 191-196; p. 195.

Coates, Paul, ‘On the Dialectics of Filmic Colors (in general) and Red (in particular): Three Colors: Red, Red Desert, Cries and Whispers, and The Double Life of Véronique’, Film Criticism 32.3 (2008), pp. 2-23; p. 11

See Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, trans. Andrew Taylor, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; p. 291. For the original French text, see Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘La nuit, l’éclipse, l’aurore’, in Cahiers du Cinéma 160 (November 1964), pp. 8-17; p. 15.

Barthes, Roland, ‘Dear Antonioni…’, trans. Nora Hoppe, in L’avventura, ed. Seymour Chatman and Guido Fink (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1989), pp. 209-214; p. 211. French text quoted from Étyen Wéry’s website. Originally published as ‘Cher Antonioni’, Cahiers du Cinéma 311 (May 1980), pp. 9-11.

Barthes, Roland, ‘Dear Antonioni…’, trans. Nora Hoppe, in L’avventura, ed. Seymour Chatman and Guido Fink (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1989), pp. 209-214; pp. 210-211. French text quoted from Étyen Wéry’s website. Originally published as ‘Cher Antonioni’, Cahiers du Cinéma 311 (May 1980), pp. 9-11.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘The girl, the crime…’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 79-86; p. 86. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘La ragazza, il delitto…’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 91-100; p. 98.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘The girl, the crime…’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 79-86; p. 86. Italian text from Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘La ragazza, il delitto…’, in Quel bowling sul Tevere (Torino: Einaudi, 1983), pp. 91-100; p. 99. Arrowsmith’s translation is used verbatim in Beyond the Clouds.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 452

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 455

It has to be said that Ossessione is more interested in the ‘existential void’ than I am suggesting here – this is a point I will come back to in Part 20.

‘A Talk with Antonioni on His Work’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 21-47; pp. 22-23

Weiler, A. H., ‘Screen: “This Sporting Life” Arrives’, The New York Times (17 July 1963)