Everything That Happens in Red Desert (1)

Loss of focus

‘Everything that happens to me is my life,’ says Giuliana near the end of Red Desert, as though arriving at a hard-won conclusion about the nature of existence. What does she mean? What has happened to her? And why do I care so much?

Welcome to ‘Everything That Happens in Red Desert’, part 1 of 52. This will be a kind of slow-motion commentary track on Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1964 film, which I have been watching compulsively for the last 16 years. The first four parts will focus on the title sequence - two on the imagery and two on the soundtrack.

The first image in Red Desert is so blurry that we may suspect there is something wrong with the cinema projector.1

After a moment, the first credit (‘ANGELO RIZZOLI Presenta’) materialises in crisp black lettering, and we realise that the image behind it is deliberately out of focus.

All 19 shots in the title sequence are afflicted with this same condition.

Red Desert is centred on one point of view – that of Giuliana, the film’s protagonist – and the title sequence shows us the world as it appears to her. Later, we will occasionally see telephoto-lens shots in which Giuliana is the only object in focus. Sometimes, as in the penultimate shot of the film, we will look at the back of her head, while also looking (with her) at the amorphous world she inhabits.

Red Desert is Giuliana’s story, and although she herself does not appear in the title sequence, this sequence lays the groundwork to make us understand how she sees, if not exactly what she sees.

The very first image of the film is a case in point, because although it is relatively easy to identify these objects as treetops, the blurring effect and the camera movement serve to de-familiarise what we see and prompt us to re-focus our attention on how we are seeing.

The image shows a cluster of trees: stone pines, also known as umbrella pines due to the distinctive shape of their canopies. They occupy the lower half of the frame. There is a large tree to the left, a smaller one to the right, and a still smaller one (with very little foliage) in between. The trunk of this third tree intersects the canopies of the other two. Its lower branches are indistinguishable from those of the other two trees, and its upper branches appear to form a semi-circle (a small ‘umbrella’) that fits snugly into the gap between the other two canopies. Antonioni said that in this film, he ‘worked hard to ensure flattened perspectives with the telephoto lens, to compress characters and things and to place them in juxtaposition with each other.’2 The long lens collapses the distance between the trees: in reality these are three distinct entities, but from our point of view it is not clear where one ends and the others begin. They are precisely correlated with each other (thanks to the careful positioning of the camera) but at the same time the relations between them are obscured.

The entities themselves are also obscured. Are these objects still trees, or have they transformed into abstract shapes? We could describe this image without reference to ‘trees’: a hazy network of black lines rises from below the frame, erupting into brownish-green clouds that dissipate into a grey void. We have zoomed in so far that the slightest movement of the camera causes the image to shudder, the film grain pulsating as though on the verge of disintegration. Another disturbing aspect of this image is the transformation of the trees’ colour. We know we are looking at green leaves, but they are reproduced so dully that they might almost be stains on the lens, visual anomalies to be wiped away with a cloth. Or, more worryingly, these stains might represent defects (like cataracts) in the lenses of our own eyes.

After seeing Red Desert for the first time, Alfred Hitchcock wrote to Giulio Ascarelli, head of Universal Films in Rome, to ask how the colour effects were achieved. Ascarelli wrote back:

Antonioni’s aim was to have a dominant grey colour, or should I say colours as soft as possible with the dominating grey tone. I understand that in shooting Antonioni avoided bright colours as much as possible.3

Murray Pomerance, after quoting this letter, argues that Ascarelli is ‘clearly wrong’, as Antonioni often uses bright colours in Red Desert. But to my eyes, most of the film (even at its brightest and most colourful) does exhibit this tendency to make greyness predominate and to make other colours softer, diminished.

The first image makes us feel that a greying, blurring, or smudging effect has been imposed on the world, resulting not only in a confusion of objects but also in a confusion of colours. Green is not what it used to be; it struggles to emerge from the grey, or to come into focus. Seymour Chatman describes the effect as ‘strong homogeneous color to promote the flat effect [of the telephoto lens] – pure, unshaded, uniform color, unattached to objects.’4 The smudged, flattened colour in the first shot is a good example. It seems more like a colour effect in an abstract painting than a filmic record of real-life trees.

The camera tilts upwards and pans right, and for a few seconds all we see is the grey sky, with the black lettering of ‘MONICA VITTI’ suspended in it.

Vitti’s name appears to be lost in that grey sky where it fleetingly (and starkly) appears, subliminally telling us something about Giuliana’s precarious status relative to the other characters (Richard Harris’s credit is firmly attached to the factories), and relative to the world. If we were confused by the image of the umbrella pines, the tilt-and-pan disorients us still further. We were looking up at the tops of the trees, with no sense of our own position or of where the ground was. As Victoria Kirkham notes:

Visually, [the trees] have been uprooted, just as in history they are dying. […] [T]hey give the film its master establishing shot, but […] the camera immediately pans through a choking haze to the petrochemical setting that has replaced the trees.5

Our gaze was already too elevated, too far above the tree-roots and the ground in which they were planted; now we find our eyes travelling even farther upwards. The tops of what appear to be lamp-posts drift through the frame. The camera ultimately settles on some tall cylindrical objects, the same ones we will see (in focus) in the final scene of the film, and from almost exactly the same angle.

But in the title sequence they are blurred to the point of abstraction. Like the trees, they are ambiguously positioned in relation to each other. When they are in focus, we can see that these towers are coupled together, but when we see them through the distorting lens, some appear singular and discrete, while others appear to be melding together.

The movement from trees to factories is, of course, a significant opening gesture in a film about the effects of industrialisation. There is a similar transition at the start of L’avventura, when the camera dollies backwards out of an ornate villa; the next shot features Saint Peter’s and an under-construction apartment block in the background. The first lines of dialogue comment on the destruction of forests and (potentially) of the villa itself to make way for the new housing blocks, and these ideas and images complement the generational conflict between Anna and her father.

In the first shot of La notte, the camera is trying to look up in respectful awe at a 19th-century Renaissance-style building, but Metalgraf and Philips vans get in the way. When they have passed and the camera tilts upwards to marvel at this ornate building, we see it overshadowed by an ultra-modern skyscraper (the recently completed Pirelli building in Milan) dominating the right-hand side of the frame.

These transitions invite us to look at the world we live in, consider how it is different from what came before, and consider the place of the ‘old’ alongside the ‘new’. In Red Desert, the transition is not from one architectural style to another, but a more radical shift from nature to artifice.

Sławomir Masłoń compares Red Desert’s hazy images to a mirage, noting that they ‘[bring] to mind the distortion of vision created by (e.g., desert) heat.’6 Consider the similar images of factories obscured by their own heat and steam in Kieślowski’s The Scar: we see those images near the end of a film that is all about the encroachment of industry on communities and landscapes, and there is no danger of our attributing natural causes (such as desert heat) to the blurring of our vision. These are not mirages – we can see where the heat is coming from, and we can see the difference between the distorted and non-distorted parts of the image.

But as Masłoń says, the Red Desert title sequence retains the quality of a mirage even after it transports us from the trees to the factories, and while we may infer that some of this haze is caused by industrial processes, it also seems to have a more pervasive and existential quality. As modern as these buildings are, their heat makes us see them as we have always seen the desert, and makes us look in vain for an oasis beyond the heatwave. After a while, we may just get into the habit of straining our eyes like this, regardless of the atmospheric conditions.

The heatwave and dust-clouds obscuring the palm trees at the start of Apocalypse Now are ambiguously poised between the natural and the man-made; the heatwave intensifies as the helicopters pass, and the dust seems, on closer inspection, to be yellow smoke from a flare. These distorting or obscuring effects are then suddenly displaced by napalm explosions that fill the entire screen. There is a link between the anxiety induced by the sweltering heat of the jungle and the horror represented by the billowing flames (as there is an aural link between the helicopter blades and the cooling fan in Captain Willard’s hotel room).

Giuliana is more like Willard than she is like Bednarz in The Scar: Bednarz can ultimately turn his back on those sweltering factories, but Giuliana and Willard carry the mirage wherever they go.

In 1955, the art critic John Berger discussed the interplay between distortion and illumination in the paintings of Giorgio Morandi:

The typical Italian light by which one sees a landscape, a house, a town, seems to emphasize the age, the comparative durability, the almost unchanging construction of the scene. The heat forms a slight haze which takes the edge off temporary, superficial details, but at the same time the constant clarity of the light exaggerates the apparently permanent identity of every object.7

When Morandi depicts a building amongst trees and hills (as in ‘Paesaggio’8 and ‘Paese’,9 below), all three categories of object seem equally amorphous – their edges wobbling as though in a mirage – and yet as Berger says this paradoxically gives them an aura of permanence. The house is not an artificial ‘scar’ violating the natural landscape, but a component of that landscape, bathed in the same Italian light and heat, and partaking of the same processes of constant flux by which the natural world sustains itself.

But the effect is less serene, and closer to what we find in Red Desert, in Morandi’s still lifes, where the mirage seems to have penetrated an interior space and made solid objects – bottles, jugs, the tables on which they stand and even the walls behind them – begin to dematerialise. In ‘Still Life’10 (below), the yellow bottle on the left appears to be ruptured partway down the neck, and the third object from the left looks (at first) like a single bottle but on closer inspection turns out to be a cup with a similarly coloured bottle behind it (and a set of darker, unidentifiable shadow-like objects in the back row on either side).

When Sam Rohdie describes how Antonioni uses the distorting/illuminating effects of weather conditions, he could be talking about Morandi as well:

Damp and humidity, which are aerial, atmospheric qualities, matters of weather, are distorting mediums through which figures and landscapes are perceived in the films, as if they are, for Antonioni, the necessary terms for visibility.11

The damp and humidity are as characteristically Italian as the light and heat Berger referred to. In one of his short stories, Antonioni notes that ‘In Ferrara, where I was born, the winter fog moves in so thickly that you can’t see three feet away,’12 and for him this is indeed a ‘necessary term for visibility’, an environment conducive to revelations about changing and unchanging things.

In van Gogh’s ‘Factories at Clichy’,13 the natural and the artificial are juxtaposed but also confused with each other. The chimneys in the far distance are vague dark smudges, barely distinguishable from the streaks of paint that denote smoke or fence-posts or factory walls.

Even on the more recognisably chimney-like shapes in the middle ground, the yellow dabs suggesting industrial stains are identical to those in the foreground suggesting yellow flowers or yellowed grass. The human couple at the centre of the painting are easy to miss: the dark figure on the left could be one of the fence-posts, and the white-and-blue figure on the right could be a wisp of smoke hanging over a blue flower. As in the pointillist artworks from which van Gogh drew inspiration, there is a tension between the coherence of the image when viewed from a distance and the exposure of the optical illusion when we look too closely. Red Desert’s title sequence looks too closely, from start to finish, like a spectator in an art gallery who never stands back from the paintings, who cannot stop seeing through the illusion.

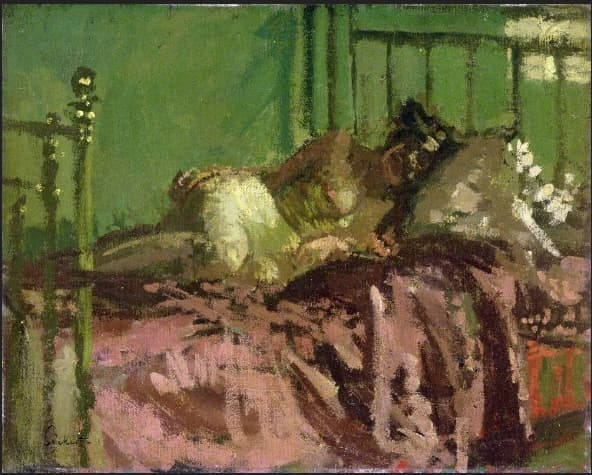

There is more to these blurred images than just this sense of a ‘too close’ perspective, however. The vibration of the film grain, the muted colours, the camera’s anxious journey from the pines to the factories – all these effects make us feel that we are looking through traumatised eyes, at a reality in which something terrible is lurking. Walter Sickert’s paintings often depict a similarly traumatised vision of reality, in which (possibly murdered) human bodies seem to be losing their facial features and decomposing into their death-beds. In ‘Le Lit de Cuivre’14 and ‘Nude Figure Reclining’,15 the grimy, smeared colours evoke a person who is barely differentiated from the squalor in which they exist. They are fading from visibility and from memory as the in-focus world leaves them behind.

Gerhard Richter is also famous for his out-of-focus paintings, in which a sfumato technique has overtaken the entire image, as in ‘Landscape Near Hubbelrath’.16

Or the more abstract ‘Forest Piece’.17

Or the still more abstract ‘Landscape’,18 in which the image is only identifiable as a landscape thanks to the title.

In a series of paintings titled ‘18 October 1977’, Richter paints the leaders of the Baader-Meinhof group, dead or about to die in their cells. The paintings are based on photographs but they deprive the original images of their clarity. In a series of three paintings based on a photograph of Ulrike Meinhof’s corpse (the last of which is shown below), the subject’s face becomes increasingly blurred until it loses all individuality.19

The effect is reminiscent of the final magnified image of the corpse in Blow-Up, an object fixated upon ‘too closely’ to the point where only the photographer, who remembers the body itself, will recognise this quasi-pointillist mess as a representation of a human being.

‘[T]he motif of the progressive enlargements [in Blow-Up],’ says Matilde Nardelli, ‘draws attention to how photography may ultimately obscure or even lose the “real”, rather than help its capture […] highlighting the medium’s inherent opacity and indeterminacy.’20 But this loss also points towards a potential gain that exceeds our grasp, an aspect of the ‘real’ that lies hidden beyond the veil of static. ‘They don’t mean anything when I do them,’ says Bill, the painter in Blow-Up. ‘Just a mess. Afterwards I find something to hang on to […] And then it sorts itself out and adds up. It’s like finding a clue in a detective story.’ Later, Bill’s wife observes the similarity between his paintings and the photographer’s blow-up, complicating the idea that the mess ‘sorts itself out’ when you stand back and gain perspective, or that the image is a ‘clue in a detective story’ with a neat resolution. The revelation produced by the obscuring lens is more like an intimation of some unspeakable trauma, and one that goes beyond the murder-mystery intrigue in which the photographer initially seems to be caught up. After the photograph is taken it ‘sorts itself out’, but then it becomes messier than ever, and then reality itself collapses; as Chatman puts it, ‘the contours seem to disappear in a general atomic welter.’21

Gerhard Richter saw his ‘October’ series as engaging with the challenge of the unspeakable or un-seeable:

All the pictures are dull, grey, mostly very blurred, diffuse. Their presence is the horror and the hard-to-bear refusal to answer, to explain, to give an opinion.22

Alex Danchev builds on this in his interpretation of Richter’s paintings:

They seem to insist that there is more to see than we can see at present, and that we are not yet equipped to see it. We need the right eyes, as Rilke remarked of Cézanne.23

Towards the end of Red Desert Giuliana will say, ‘There is something terrible in reality, but I don’t know what it is. No one will tell me.’ The blurriness of her reality is indicative of ‘something terrible’, and she is afraid of the amorphous, unknowable world that appears to surround her. But as we will see, this fear goes hand in hand with her desire to blur things together, to love everyone and everything at once, to have them surrounding her like a wall. The blurring effect in the title sequence not only makes the factories unsettling, it also makes them strangely beautiful, just as Richter’s paintings-of-photographs imbued those traumatic scenes with a kind of beauty. Perhaps the ‘something terrible’ is also ‘something beautiful’ because it represents a truth we are striving to apprehend. The title sequence of Red Desert makes familiar entities mysterious, to suggest that we were missing something when we saw them in focus, and that this ‘loss’ of focus is also a groping towards a new way of seeing. From the outset of Red Desert, we see the world through new eyes. There is ‘more to see’ in this reality, and even if we are not yet equipped to see it – even if we will never have the ‘right eyes’ – we sense it in other ways and compulsively strive to unveil it.

Next: Part 2, The desert and its colours.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

All screenshots from Red Desert are taken from the BFI blu-ray unless otherwise stated. There are (sometimes significant) differences between editions, especially with regard to colour, and I will note these in footnotes or in the main text where relevant.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘It was born in London, but it is not an English film’, trans. Allison Cooper, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 89-91; p. 90

Pomerance, Murray, ‘Notes on Some Limits of Technicolor: The Antonioni Case’, Senses of Cinema 53 (December 2009)

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 122

Kirkham, Victoria, ‘The Off-Screen Landscape: Dante’s Ravenna and Antonioni’s Red Desert’, in Dante, Cinema, and Television (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), pp. 106-128; p. 125

Masłoń, Sławomir, Secret Violences: The Political Cinema of Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960-75 (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2023), p. 109

Berger, John, ‘The Metaphysician of Bologna: John Berger on Giorgio Morandi, in 1955’, ARTnews (November 2015). Originally published in ARTnews (February 1955).

Morandi, Giorgio, ‘Paesaggio’ (1934), Galleria d’Arte Maggiore, Bologna, Italy

Morandi, Giorgio, ‘Paese’ (1936), Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome, Italy

Morandi, Giorgio, ‘Still Life’ (1956), Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, U.S.A. / SIAE, Rome, Italy

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 99

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘That Bowling Alley on the Tiber’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 69-74; p. 74

van Gogh, Vincent, ‘Factories at Clichy’ (1887), Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis, U.S.A.

Sickert, Walter Richard, ‘Reclining Nude (Le lit de cuivre)’ (1905/1907), Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery

Sickert, Walter Richard, ‘Nude Figure Reclining’ (1912), The Collection: Art & Archaeology in Lincolnshire (Usher Gallery)

Richter, Gerhard, ‘Landscape Near Hubbelrath’ (1969), Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, Aachen, Germany. Additional information available on Richter’s website.

Richter, Gerhard, ‘Forest Piece’ (1965), Böckmann Collection, Neues Museum, Staatliches Museum für Kunst und Design, Nuremberg, Germany. Additional information available on Richter’s website.

Richter, Gerhard, ‘Landscape’ (1965). See Richter’s website.

Richter, Gerhard, ‘Dead [3]’ (1988), The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, U.S.A. The full cycle of paintings in the ‘18 October 1977’ series can be seen, with accompanying commentary, on Richter’s website.

Nardelli, Matilde, Antonioni and the Aesthetics of Impurity: Remaking the Image in the 1960s (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), p. 134

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 152

Danchev, Alex, On Art and War and Terror (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), p. 13

Danchev, Alex, On Art and War and Terror (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), p. 23

This is brilliant. I'd been meaning to watch Red Desert for the longest time. For some reason, I kept deferring it. Last night I did. Much to love/admire of course. Mostly, still processing. I'm now looking forward to reading through your posts. Thanks.