Everything That Happens in Red Desert (10)

Night terrors

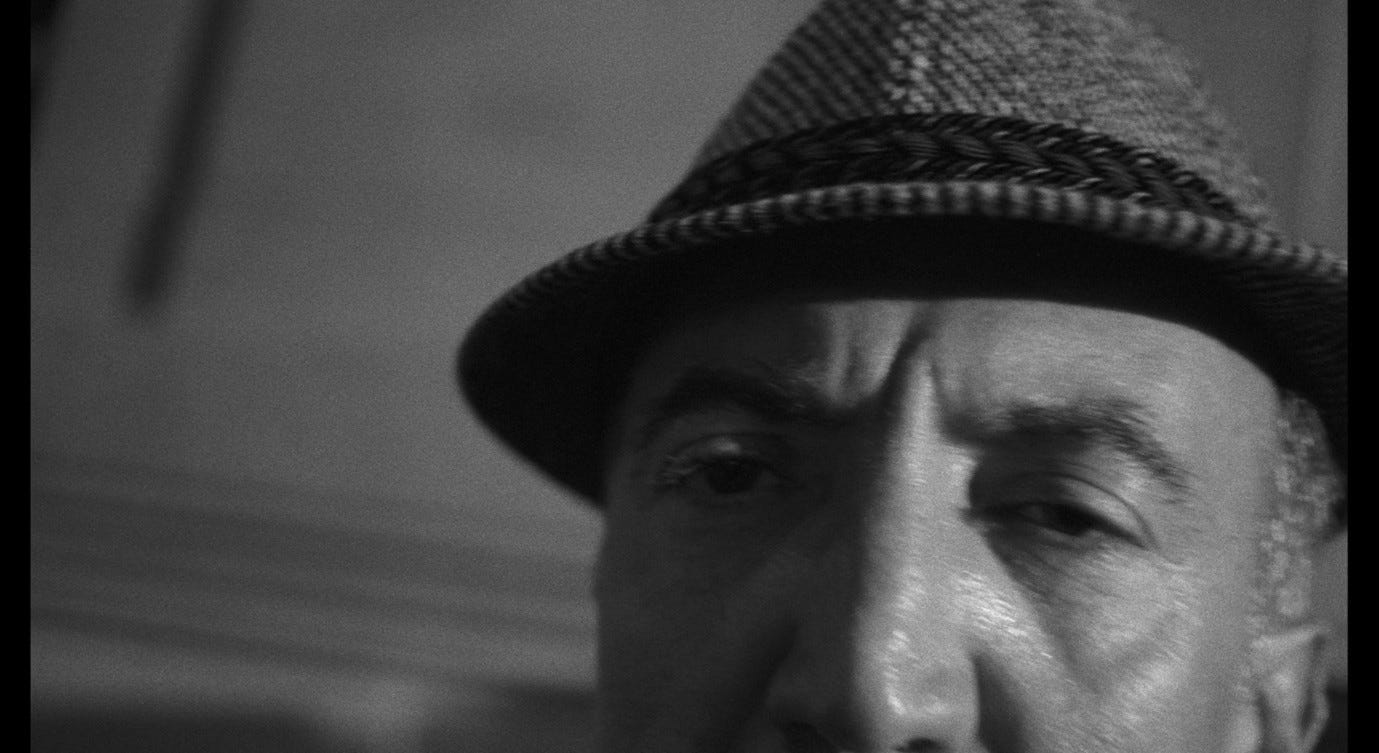

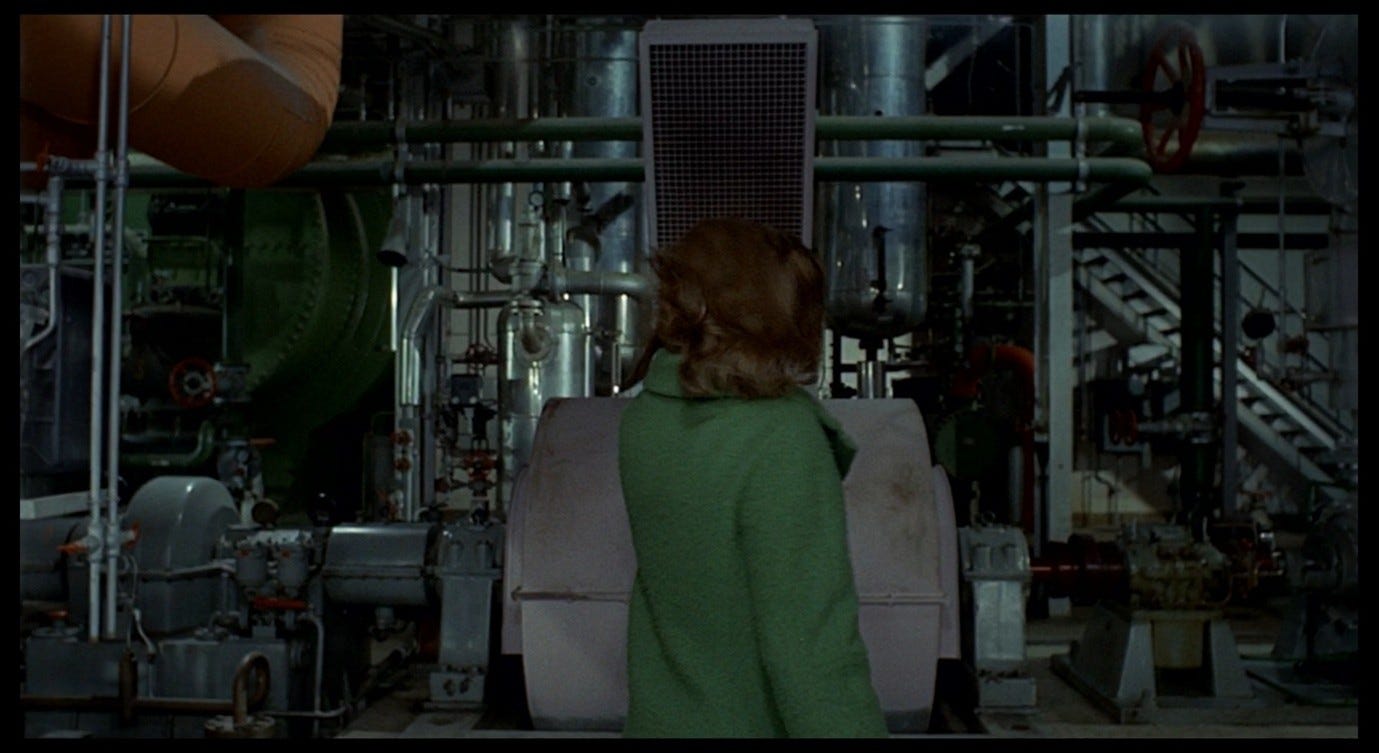

As we get our first glimpse of a domestic setting in Red Desert, we discover that Giuliana is as angst-ridden at home as she is among the factories. Indeed, there is not much to distinguish these two spheres of her existence. When she goes for a lunchtime walk with her son, she walks through the industrial complex. When she wants to talk to her husband, she searches the inner labyrinth of his workplace, only to tell him that she will wait for him at home (having found that he is busy). By cutting dramatically to Giuliana’s night terrors following the quiet-after-the-storm at the end of the steam-cloud sequence, the film retroactively associates that sequence with Giuliana’s bad dream.

The ‘night terrors’ sequence gives us a more intimate and revealing insight into the nature of Giuliana’s anxiety, by telling us, showing us, and pointedly not showing us some of the nebulous horrors that she encounters. These things are in Giuliana and her surroundings; they are also (as I will discuss in Part 11) in her loved ones and in the blurred spaces between these categories.

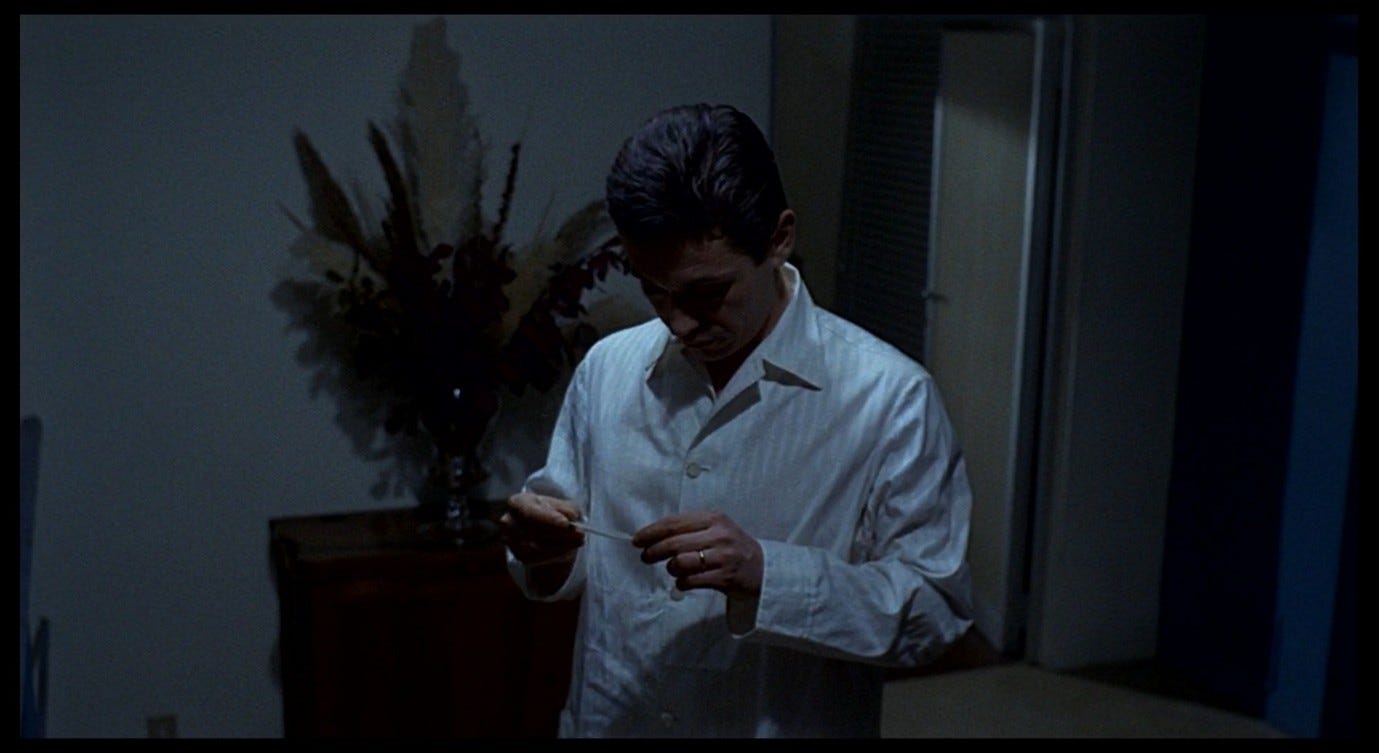

The first thing Giuliana does when she wakes up, after turning on the light, is to thrust a thermometer into her armpit.

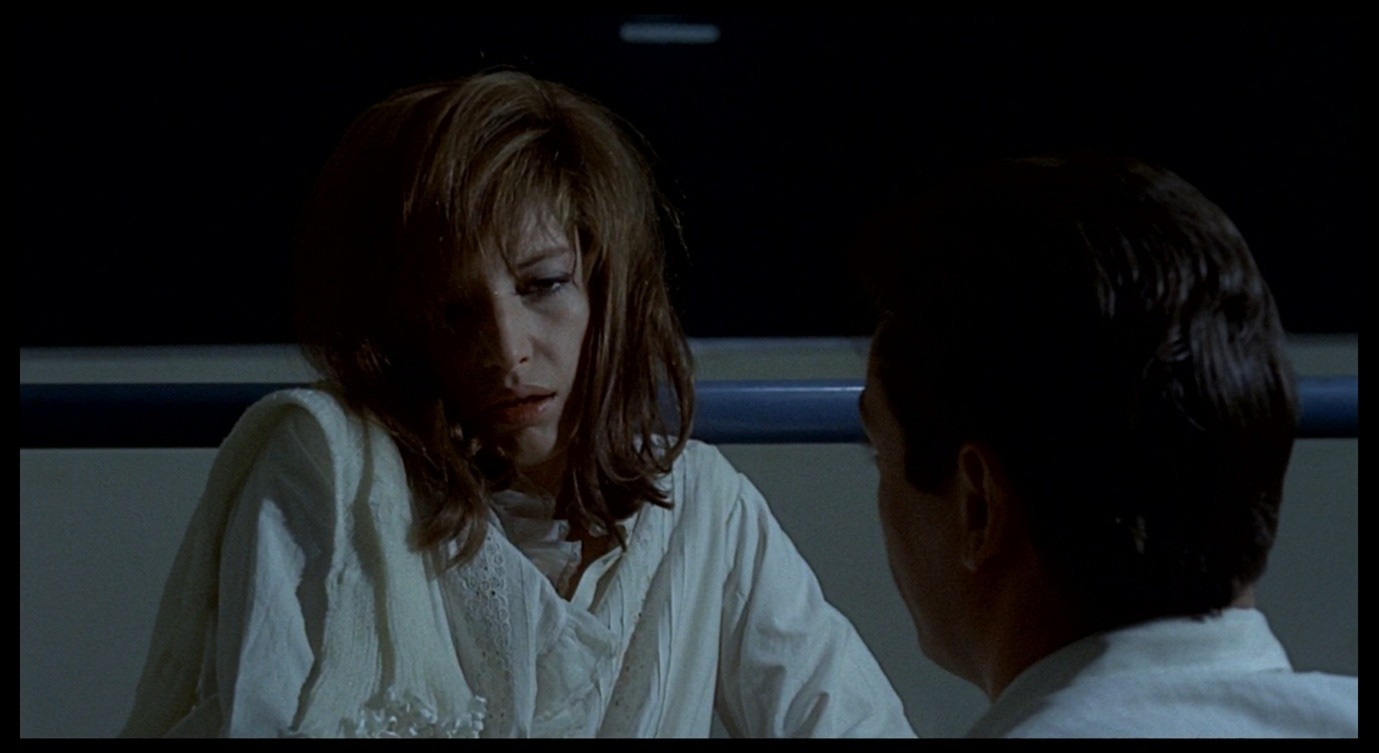

She later tells Ugo that she is running a temperature. Although he casually denies this, Giuliana seems convinced that something is wrong with her own body. As she lies still in bed waiting for the thermometer to gauge the level of her fever, she also appears to be listening to her own pulse, gradually calming down as the pounding in her ears subsides.

Giuliana’s conviction that she is over-heating from within recalls the previous scenes’ focus on heat and ventilation. When a colleague tells Ugo that the industrial vapour is running too hot, it is a simple matter to implement cooling procedures. The various-sized jets or clouds of flame, smoke, and steam that we see emanating from the factory are of the exact proportions needed to maintain equilibrium. In contrast, Giuliana lacks the ability to self-regulate. She is feverish and her heart races out of control.

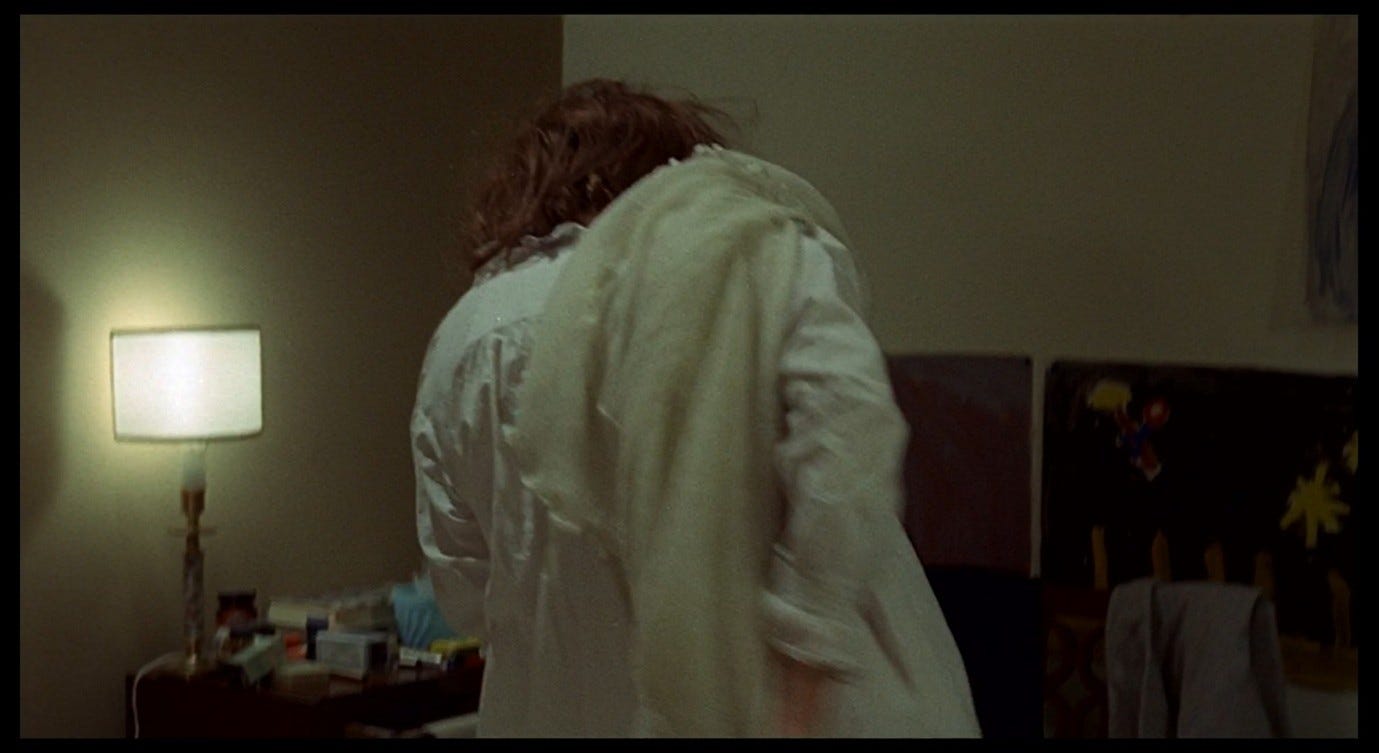

The dysregulation that affects her pulse and temperature also seems to affect her muscles. Before this, we have seen that Giuliana’s speech and gestures are characterised by indecision, and here too her movements are hesitant. She clumsily wraps a shawl around herself as she gets out of bed. She gingerly strokes her son’s hair (the screenplay calls it a ‘carezza incerta’, an ‘uncertain caress’).1

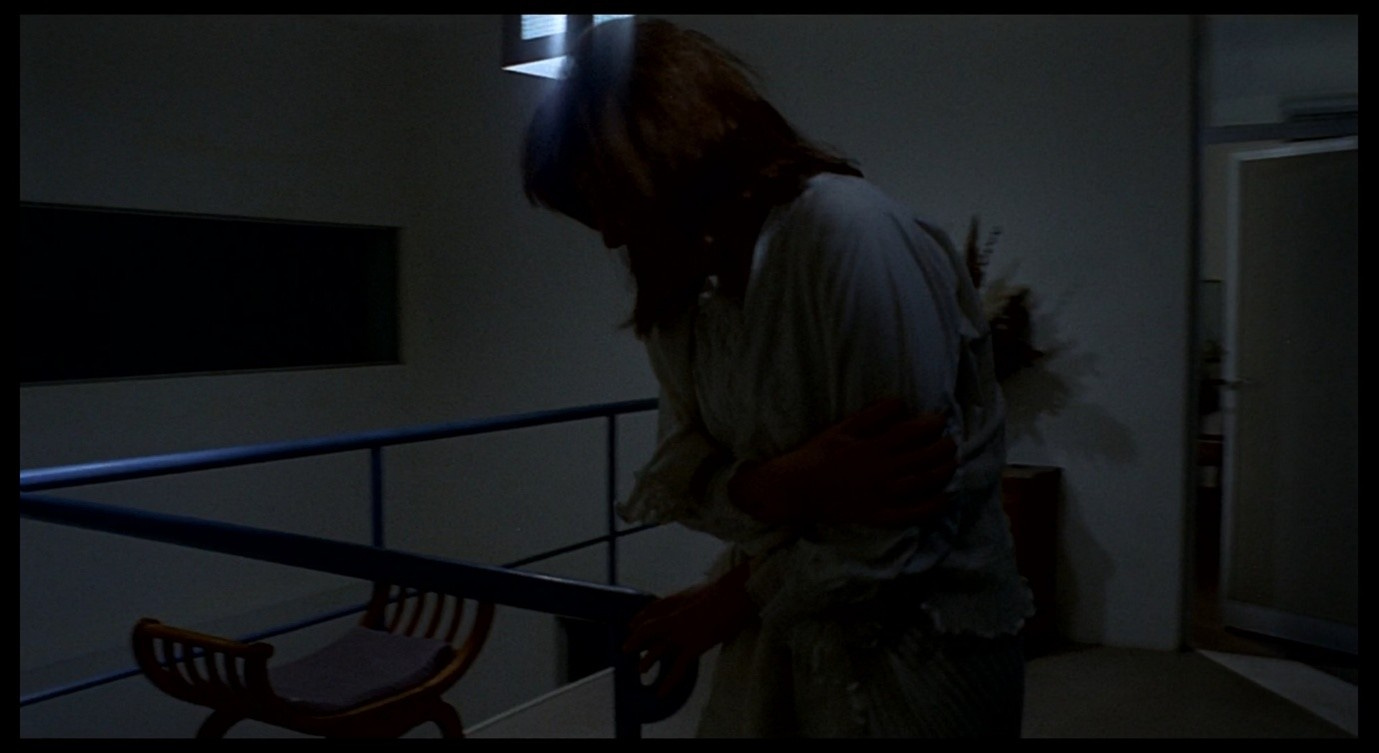

But we also start to see more extreme physical manifestations of her anxiety, as she writhes about on the chair and in her husband’s arms, stretching and contorting her limbs, darting her head around, and clawing at her own face.

At times, these movements seem involuntary, like epilepsy or demonic possession, but Giuliana also appears to be grasping – quite deliberately – for something that is not there. She extends her legs as though she were yawning, as though to dispel an inner fatigue and stiffness, but also as though she hopes to find something different in the carpet as she scrapes her heels along it, or in the bars behind her as she presses her back against them. The dysfunction is not only in her own body, but also in the external world that this body encounters.

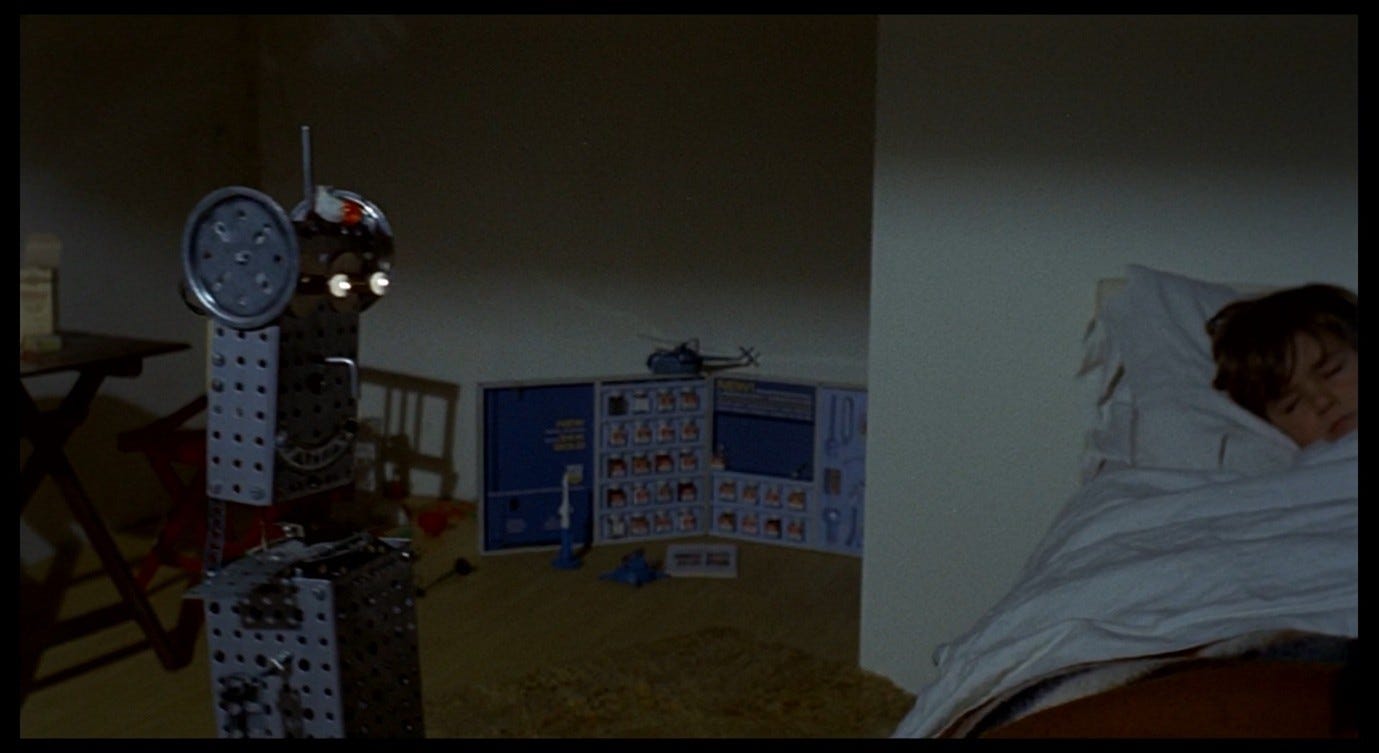

The film suggests, through the juxtaposition of the steam-cloud sequence with this one, that industrial phenomena intrude upon Giuliana’s sleep as much as upon her waking life. The home she wakes up in is anything but a safe, comforting environment. Having got out of bed, Giuliana is immediately drawn to Valerio’s room, where she finds a robot patrolling back and forth, whirring as it moves and clashing noisily against the wall.

This repetitive mechanical noise may well be the thing that disturbed Giuliana’s sleep. She switches the robot off even though it clearly is not disturbing Valerio, and even though he must have deliberately assigned it to all-night patrol duty. When Godard asked Antonioni whether the robot was a good or an evil presence in Valerio’s life, Antonioni replied:

A good one, I think. Because if he gets used to that sort of toy, he will prepare himself for the type of life that is awaiting him. […] Toys are the product of industry, which through them exercises its influence also over the education of young children. […] I feel very envious of such people. I really wish I were already part of that new world.2

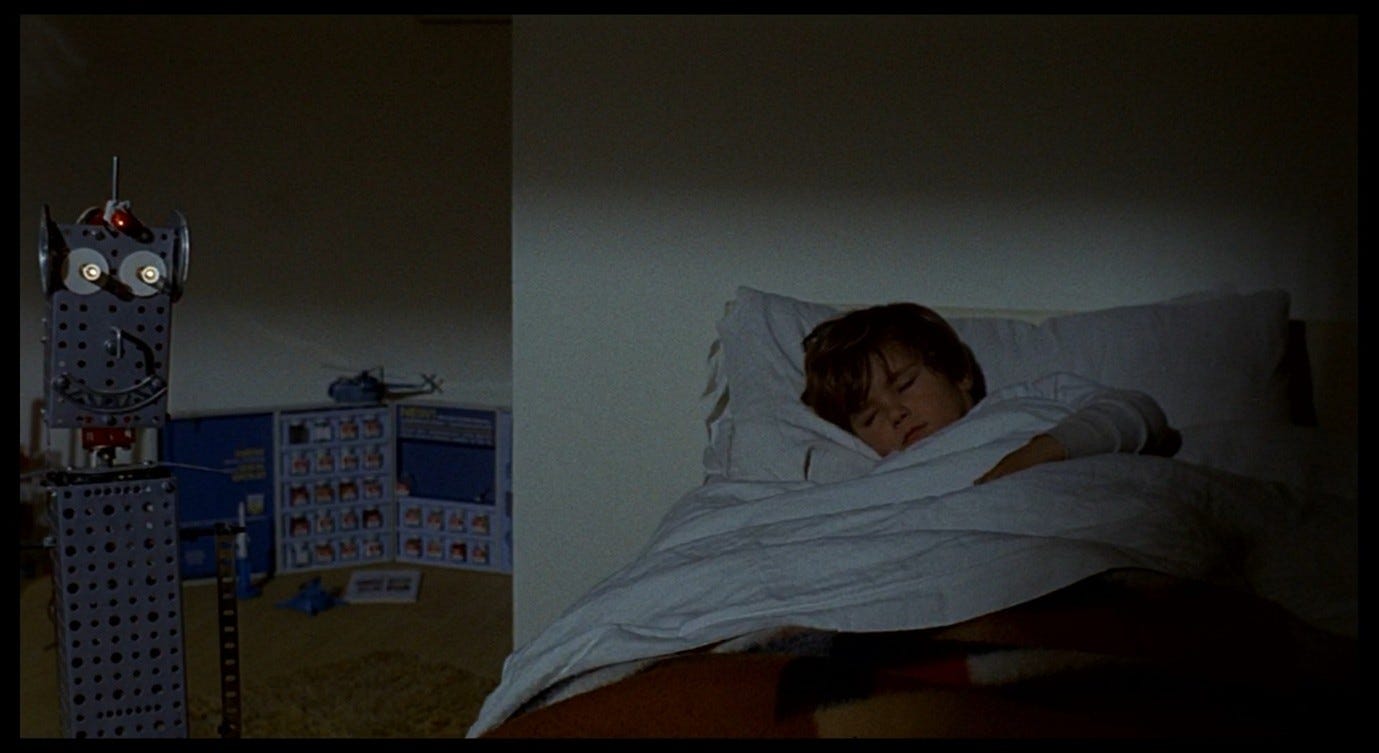

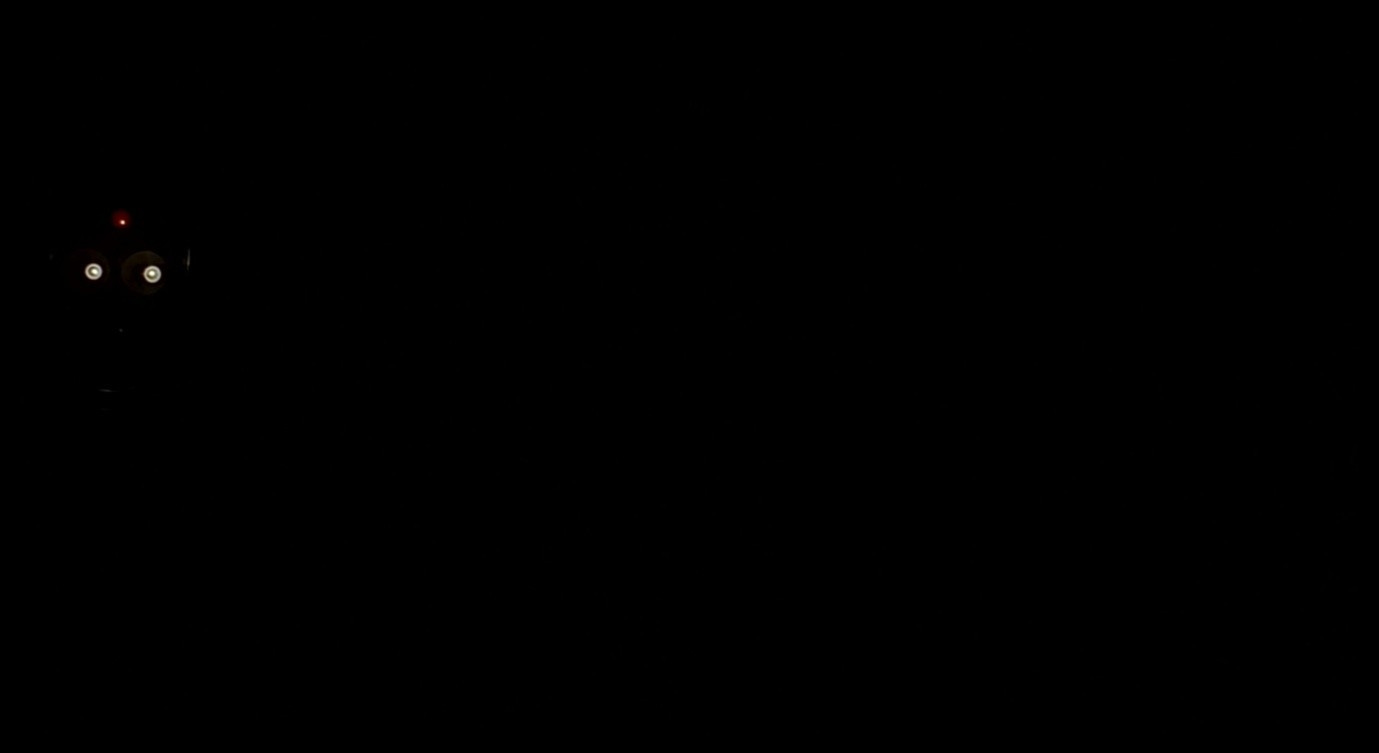

The implication for Giuliana is clear: her son is being acclimated to the modern world by the products of industry, but she (like Antonioni) has not been acclimated. Valerio has learnt to find the robot-sound soothing, but Giuliana cannot stand it. Although she stops the robot from moving, its eyes continue to shine vigilantly in the darkness, suggesting that the threat it poses to Giuliana has not been neutralised.

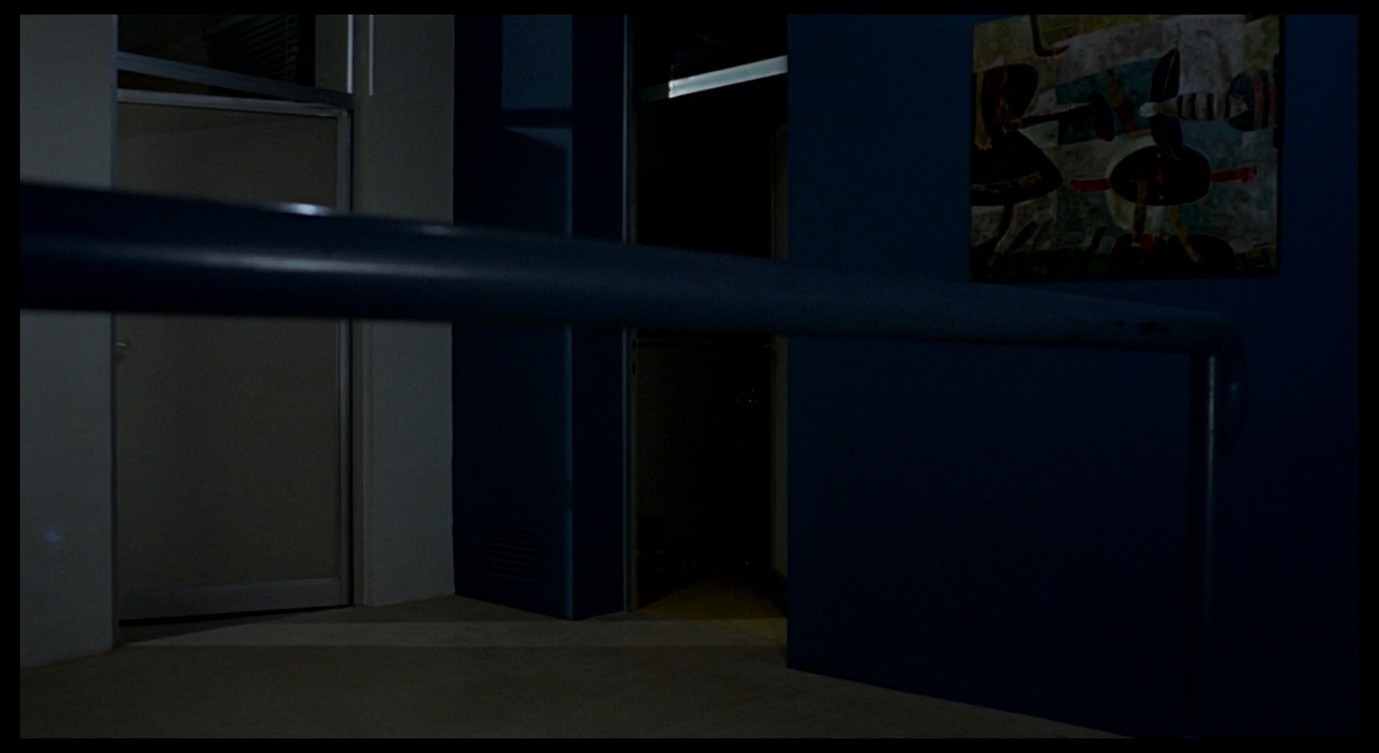

No sooner has she silenced the robot than an even more disturbing noise invades the soundtrack. It is like the electronic music we heard in the title sequence, but now instead of spasmodic bursts of robot-song, Vittorio Gelmetti has composed a high-pitched, oscillating electronic hum. This hum recalls the ambient factory noise but is also suggestive of ghostly, howling winds. The camera dollies towards Giuliana as she crosses the landing, then pans left to watch her descend the stairs.

She does not seem to respond to the music, lending it a kind of dramatic irony typically found in horror films. There is a danger lurking somewhere and we sense it before Giuliana does. A higher-pitched tone, like a boiling kettle, is layered onto the ambient hum as Giuliana arrives at the turn in the staircase.

The kettle-noise stops abruptly – like a predator becoming still and silent before attacking – as Giuliana looks down. She recoils from something in the darkness below, clutching her shawl and backing away.

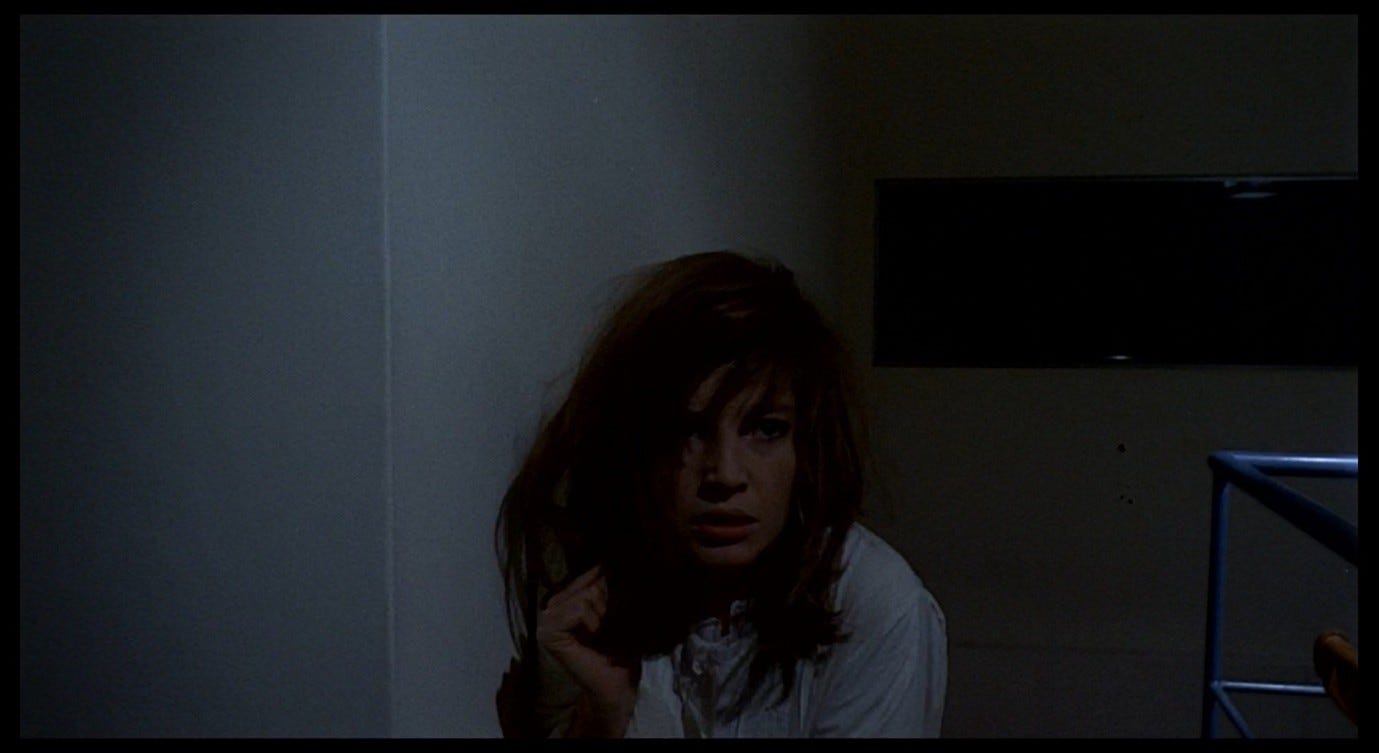

We glimpse the darkness of the lower floor on the right-hand side of the frame, and we can also see the darkness outside through the windows above the stairs and in this medium shot of Giuliana’s reaction.

We sense that she is surrounded by darkness, but we do not then get a reverse-shot of what she sees at the bottom of the stairs. This moment of horror therefore contrasts with the moment when Giuliana stood petrified by the sight of the slag-heap: in that scene, we saw her reaction first, then the thing she was looking at.

Now, in Giuliana’s home, we sense a darkness in front of her and a darkness behind her, but this time we get no indication of what is in the darkness or why it is so frightening. Even a reverse-shot of the stairs descending into the unlit room below would give us too much information: it would suggest that Giuliana is afraid of the dark, which would be too specific to capture the required sensation here. The screenplay states that she grabs the banister and widens her eyes, ‘as though terrified by the darkness that floods [invade] the ground floor.’3 But in the finished film, without a clearer indication that she is responding to ‘the darkness’ as such, we are left not knowing what Giuliana sees. David Forgacs describes Red Desert as ‘an experiment in making the exterior surroundings both manifest and condition the interiority of a character,’4 and expands on this idea in relation to the ‘night terrors’ sequence:

[B]uilt space does not simply frame or set off the body of the character but enters into a tense, even hostile, relationship with it. The viewer can feel that it is almost as if Giuliana shudders and shivers because of what is physically around her (hence, perhaps, her startled look ‘into empty space’) as much as because of what is happening inside her.5

The darkness in the lower floor manifests something in Giuliana that is too ‘interior’ to be shown on film, yet it also suggests how that interiority has been conditioned by the surrounding environment. Giuliana’s body is itself a kind of ‘built space,’ shaped and made sick by the structures of the modern world, and now reflecting and responding to those structures as both causes and symptoms of her sickness. The shadows in her home come to embody the shadows in her psyche; the humming of the wires and pipes resonates with her troubled nerves.

The effect of this moment is similar to (though less extreme than) Karin’s frenzy at the end of Through a Glass Darkly, which the camera unflinchingly records without ever letting us see what is causing it. Karin is in a vacant attic room, seeking an encounter with God. A door creaks open, revealing nothing but darkness behind it. Then we watch Karin, from the other side of the room, as she erupts into terrified screams, apparently in response to an entity that remains invisible to us and to her family.

There are no more reverse-shots, either of the creaking door or of anything else Karin might be looking at. We can only spectate her harrowing facial expressions and guttural cries of terror, and try to infer from them what she has seen. A minute later, when she has calmed down, she describes her vision. She saw the cold-eyed spider-creature that occupies the void left by the absent God in Bergman’s ‘faith trilogy’:

The door opened, but the god that came out was a spider. He came towards me and I saw his face. It was a terrible, stony face. […] The whole time, I saw his eyes. They were cold and calm. […] I have seen God.

Karin’s vision was perhaps (though she does not say this) a manifestation of her feelings about her cold, callous father. But it also transcends both of these meanings to suggest a trauma that cannot be depicted visually or articulated in words.

The original Swedish title of Bergman’s film is Såsom i en spegel (‘as if in a mirror’). What Karin sees is a reflection of a nightmare from her own inner life, which in turn mirrors the nightmares lurking in her familial relations, which in turn mirror the broader nightmare of existence itself. The title is taken from the Bible: ‘For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.’6 The allusion works on several levels. Bergman’s title misses out the word ‘dunkelt’ (‘dimly’) from the Svenska 1917 version, but there is an allusion to this in the darkness behind the creaking door, which is part of what Karin sees. During her visionary experience, we only see Karin’s face, not the other face she is looking at. As with Antonioni’s motif of kisses-through-glass (discussed in Part 9), there is an ambiguity as to whether we see as if in a mirror, as if face to face with another person, or as if into a dark abyss (or into a face that is also a dark abyss).

During these unsettling encounters in Red Desert and Through a Glass Darkly, we experience a combination of empathy and detachment. Like the concerned bystanders in both films, we cannot look away from the suffering subject or her feelings, but also like them we find ourselves studying that subject with an objectifying, analytical gaze. Perhaps we fail to see what she sees because we do not share her illness. Or perhaps we are ill enough that we do not need a reverse-shot, and we understand Giuliana’s and Karin’s reactions because we have had these ineffable, un-photographable waking nightmares ourselves. But perhaps, even in this latter case, it is the very feeling of recognition that makes us feel cold, or that makes us look away. We know from experience that these nightmares cannot be communicated to others, so we are all too aware of the gulf that separates us from Giuliana and Karin.

Sam Rohdie describes the ‘errors in identifying’ sometimes occasioned by Antonioni’s camerawork, which invites us to ‘[put] ourselves in the place of another which evaporates as no place at all (the “subjective” gaze of the characters),’ and his conclusion on this topic sounds like a subversion of the epiphany envisioned in Corinthians:

[T]he fascination remains in the in between-ness, and the knowledge that even if a place has been at last arrived at, it will only be temporary, will itself be threatened with erasure, with doubling, with doubt.7

What Rohdie describes as a source of fascination is also one of the main sources of Giuliana’s and Karin’s anxiety. Both characters are overwhelmed with fear when they look towards the camera – towards us – because they arrive at a place of seeing something, but seeing it darkly, as if in a mirror, and with no sympathetic face to return their gaze or empathise with them. Later in his book, Rohdie develops this argument in relation to Giuliana:

[T]hough the camera is often subjective, that subjectivity and subjective look is in turn ‘objectively’ regarded; Giuliana’s subjectivity is more an ‘object’ observed than a subjectivity to identify with.8

I would argue it is the other way around – that despite the objectifying regard of the camera, Giuliana is more a subject to be identified with – but this ambiguity is part of what makes Red Desert so powerful.

What Giuliana sees is not terrifying because it lurks within literal darkness but because it is metaphorically ‘in the dark’. It is one of the ‘terrible things in reality’ that neither she nor anyone else can identify. One crucial factor in this case is that the thing lurks somewhere in Giuliana’s home. There is something terrible about the ground floor of this house that sends her back upstairs, not to a specific room but to the liminal space of the landing. Giuliana has fled her bedroom, found a demon-eyed robot in her son’s room, and recoiled from the entire lower floor. She is then reduced to writhing uncomfortably on a chair that provides no back support. The home, in its entirety, has become the setting for Giuliana’s own private horror film, menacing her from all sides without ever unleashing the monster to finish her off.

As we cut from Giuliana on the stairs to her return to the landing, another layer is briefly added to the high-pitched horror-suspense noise on the soundtrack. The transition is disorienting because the film does not cut ‘on action’: we would expect to see Giuliana (in the first shot below) turn to her right and begin to re-ascend the stairs, then we would cut to the view from the landing as she arrives back in that space. We feel that something is missing here - a moment of trauma has been blacked out - and the visual disorientation is matched by the sudden shift in the soundscape.

This new sound is lower-pitched and fades away within seconds, like an electronic imitation of a bell (reminiscent of Stockhausen’s ‘Studie II’, discussed in Part 3). The high-pitched whine fades away too and is replaced by a sort of rapid electronic bubbling noise as Giuliana gropes for the thermometer.

When she then checks her temperature, the bubbling noise is replaced by a low, pulsing alarm and a tinnitus-hum, very high-pitched but quieter than the boiling-kettle noise from a few seconds earlier.

All these sounds dissolve into silence as Ugo appears in the bedroom doorway.

On the one hand, this electronic ‘music’ seems extra-diegetic in the way that it underscores Giuliana’s emotions (her palpitations as she searches for the thermometer, her alarm when she sees the result). On the other hand, the music seems to inhabit Giuliana’s immediate environment, like source music. Just as the volume of the factory noises changed depending on the position of the camera, so in Giuliana’s home the electronic music changes as she and/or the camera move from one place to another. The cut from the stairs to the landing is the most obvious example of this.

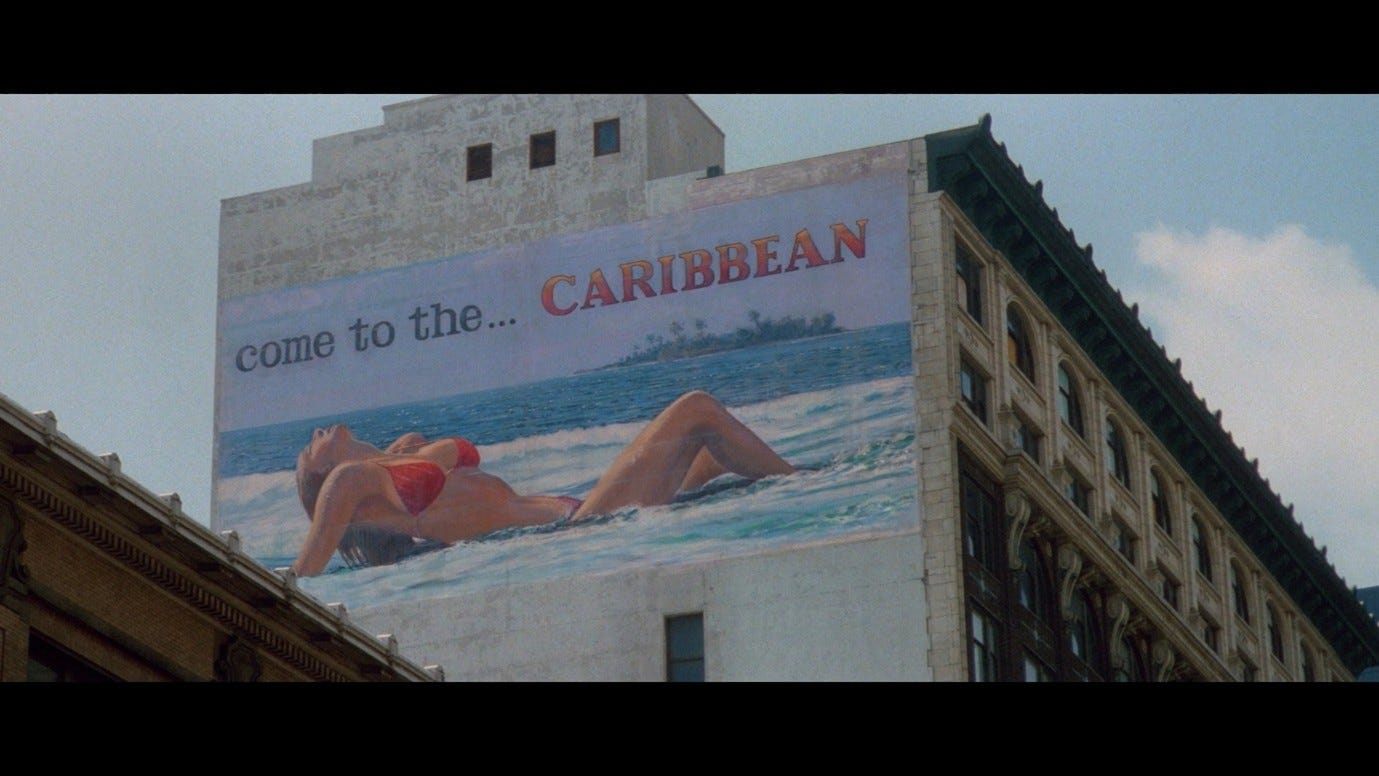

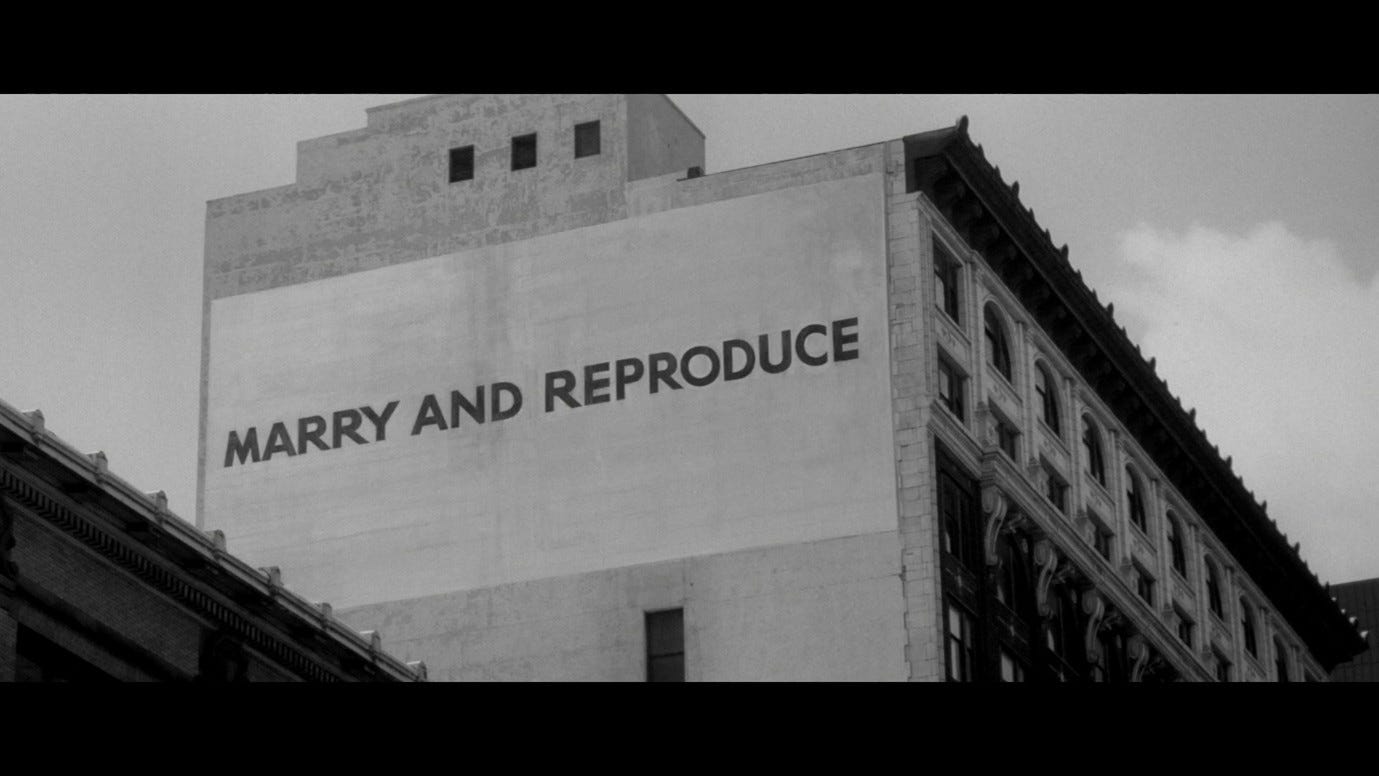

In Zabriskie Point, when Mark is driving through the streets of Los Angeles, we hear jarring noises on the soundtrack. They accompany images of signs and billboards rushing by outside, and seem in some way to emanate from these ‘loud’ advertisements. At first, we hear a pounding factory noise coming from the steelworks, but this quickly turns into a series of electronic effects that play over blurry images. Effectively, this latter part of the montage is a reprise of Red Desert’s title sequence.

We are perceiving a layer of reality that is normally invisible and inaudible to us, but that Mark perceives all the time – hence his agitation and rage. As Rohdie says, Mark is ‘picking up the whole world in [the car’s] windows and its mirrors,’9 but this works on the aural level as well as the visual. The voices, melodies, and images that surround Mark are conflated into a cacophony of static and feedback, from which he can only escape in Death Valley. Steven Jacobs argues that Antonioni is here visualising America

in the American way – that is, from the perspective of the car. […] While the periphery of European cities in La notte, L’eclisse, and Il deserto rosso is defined by an almost geometrically designed emptiness, Los Angeles is foregrounded as an avalanche of interchangeable signs of corporate power and injunctions to consume.10

The car enables Mark to perceive the signs of Los Angeles at great speed, in a blurry montage that makes their impact on him subliminal (as it is meant to be) but that also reveals their homogeneity and exposes their messaging as empty, inhuman noise. For Mark, this ‘American way of seeing/hearing’ involves succumbing to the propaganda while being aware that it is propaganda. There is something ‘broken’ about both Giuliana and Mark, and the soundtracks evoke their inner disorder; but they are also like the heroes of They Live, whose eyes (and in this case ears) have been opened to the ‘broken’ reality through which the rest of us are sleep-walking.

Antonioni’s comments on America reveal the same ambivalence he expressed on the subject of technology: ‘[America] thrills me when I understand it. It depresses me when I don’t understand it.’11 In another interview just before the making of Zabriskie Point, he talked about the environment of Los Angeles in ways that resonate with the alterations of perspective in They Live:

The billboards are an obsession of Los Angeles. They are so strong that you can’t avoid them. Of course, there is the danger of seeing Los Angeles as a stranger. To us the billboards are so contrary, but for people who live there they are nothing – they don’t even see them. I am going to show them in [Zabriskie Point], but I don’t yet know how.12

The disturbing sound effects during Mark’s car-ride through the city indicate that he too is a stranger here, that he finds the billboards and other aspects of his milieu ‘contrary’. Antonioni refers to the ‘danger’ of contradicting your surroundings, but he also regards this as a way of ‘seeing what others do not see,’ of awakening to an obsession that others have learnt to sleep through. In a sense, he is saying that Los Angeles is sick – in thrall to an unexamined mania – and Red Desert suggests something similar about industrialised Ravenna.

In The Devil’s Trap, Zdeněk Liška’s score evokes a sense of uncanny dread in different ways: there are sustained notes on a pipe organ and dirge-like chants (appropriate to the medieval setting) but also electronic effects such as a tinnitus-whine. The priest hears this electronic tone while riding along the road.

The voice of Filip, from behind him, echoes in a distorted form that anticipates the ‘ba-da-da-dao’ voices in The Conversation. When Filip raises his voice, this seems to trigger the higher-pitched tone. ‘The earth itself speaks,’ says the miller who is alleged to be in league with the devil, and who is then told that he listens too much to these ‘voices of nature’ instead of listening to God. The organ-notes, chants, electronic whines, and echoing pulses we hear at key moments during the film are all meant to suggest these voices of nature. They resonate from a deep, dark, unseen place, associated with all the forces that are perceived as threatening by the religious authorities – the forces that, like Bergman’s spider, testify to the absence of God. For the miller, his son, and Martina, being allied with nature represents an escape or liberation from the repressive powers-that-be, but the film (like Zabriskie Point) also plays on the ambiguity of this liberation. In one scene, the earth literally breaks open and swallows the dancing villagers.

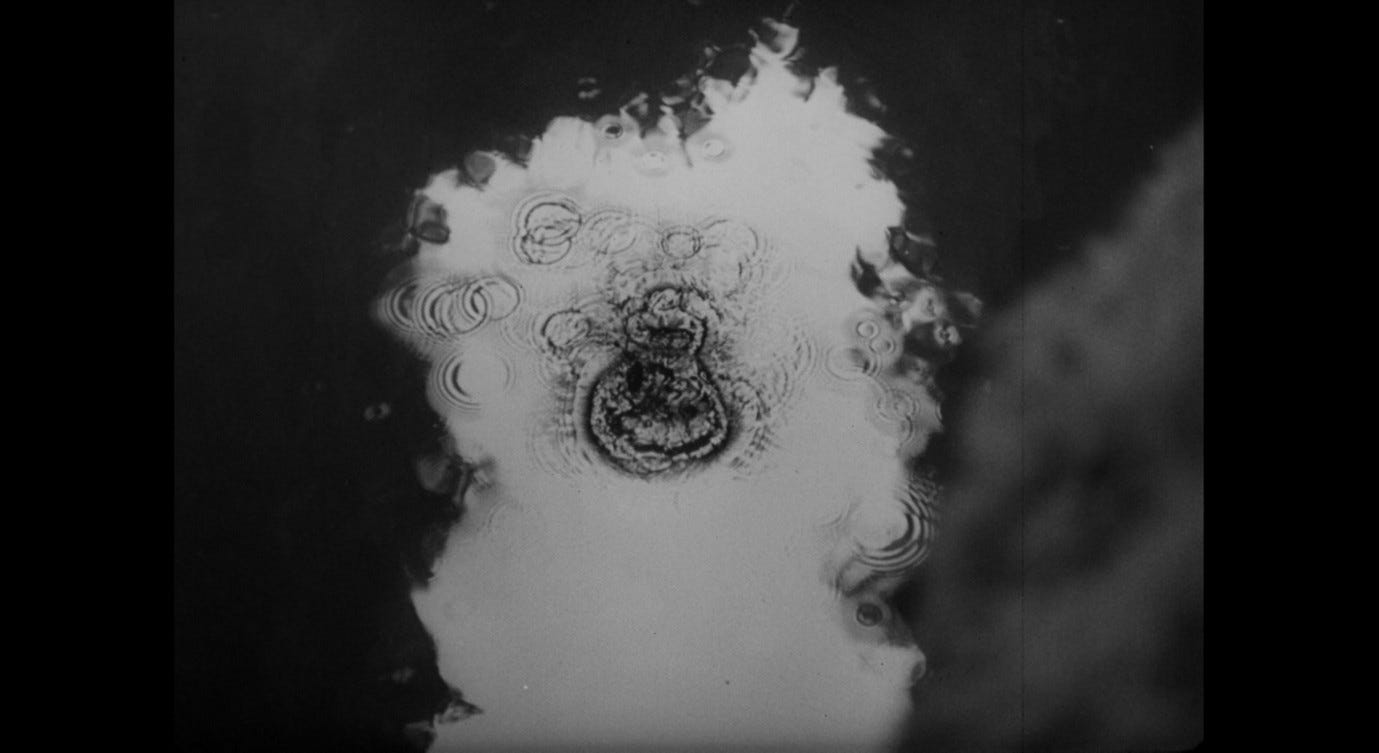

In another, an echoing pulse emanates from a bottomless pool, into which the miller may have fallen (or been thrown). When Jan throws a flower into the pool, we see the sky reflected in it. But when we cut back to the pool after a reverse-shot of Jan, the sky is gone and we see only darkness in the water.

These sounds represent energies that can be harnessed but that can also destroy us – even if we learn to live in accord with them, we should still fear them.

Jerry Goldsmith’s score for Seconds begins with a combination of electronic and traditional instrumentation that Liška might have admired. We hear a high-pitched note echoing rapidly, then sinister violin and piano notes underneath it. Suddenly a pipe organ crashes into the soundtrack as the title appears on the screen. The title sequence shows images of facial features, seen from disorienting angles and then distorted beyond recognition.

Like The Devil’s Trap, Seconds plays on the archaic narrative of the Faustian pact, but from a godless, postmodern perspective. The avant-garde music sounds like waves of quasi-demonic evil, transmitted by electronic devices or lurking in the de-humanising ideologies that plague these characters. It is reminiscent of a distant past - Goldsmith alludes to Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor, with its gothic-horror associations - but also disturbing in a ground-breakingly modern way. (Goldsmith’s score for Planet of the Apes, two years later, is regarded as a major milestone in the use of atonal music in Hollywood films.) In Seconds, there is a strong sense that something is broken in the world we are looking at through these fish-eye lenses and SnorriCams that do not quite let us see people face-to-face. We look and listen through glasses and mirrors, darkly and distortedly.

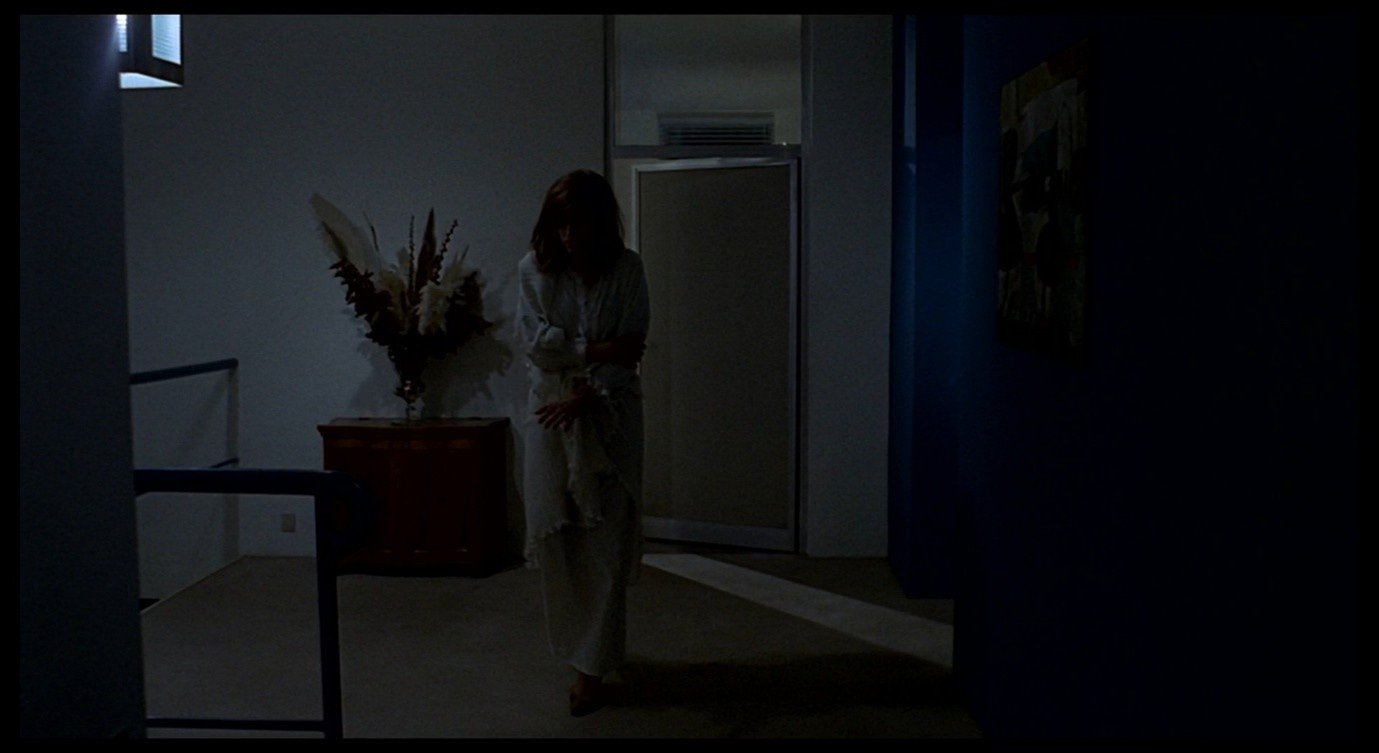

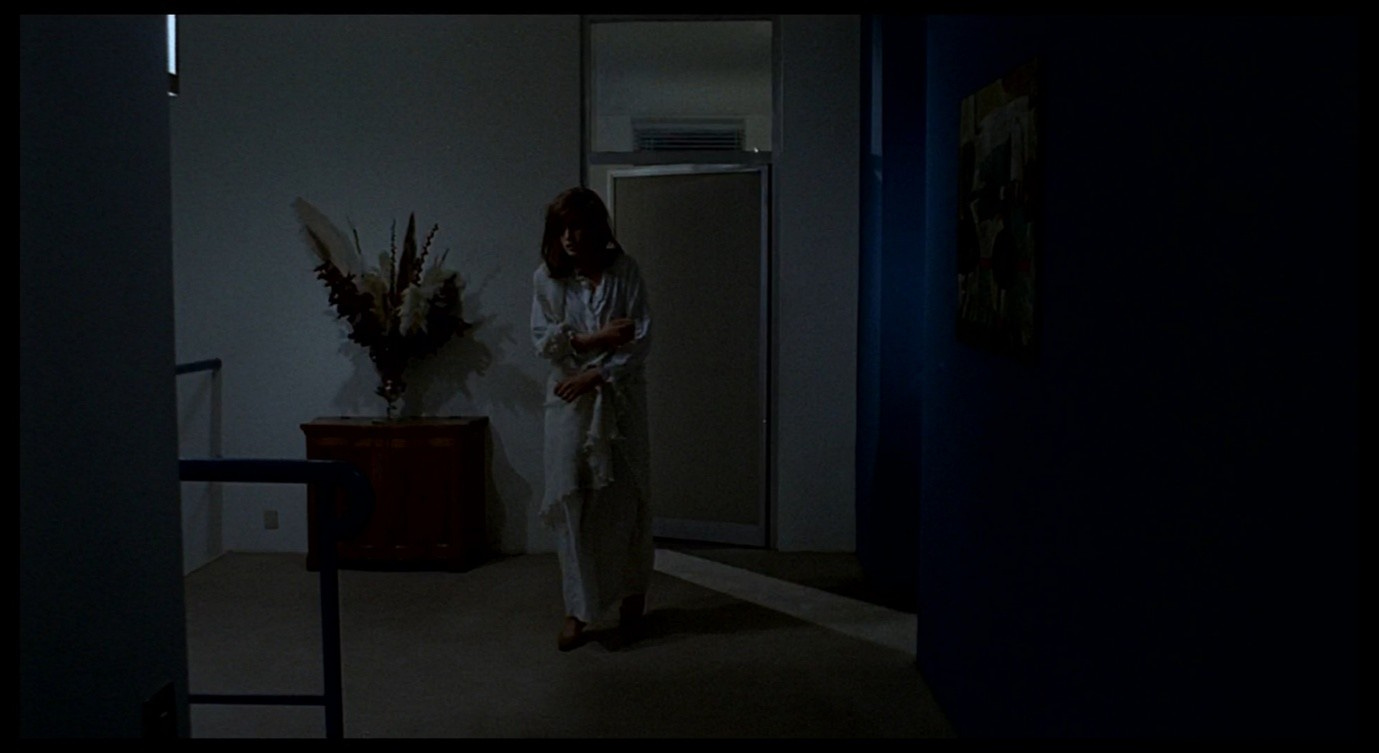

To return to Red Desert: what exactly is ‘broken’ in Giuliana’s home environment? We have escaped from the flames, slag-heaps, and labyrinthine factories, into a space that is oppressively sterile and uncluttered. Giuliana, dressed in white against bare white walls and beige floors, looks almost like a hospital patient. This effect is underlined when Ugo, in his lab-coat-like white pyjamas, shows up to read her thermometer.

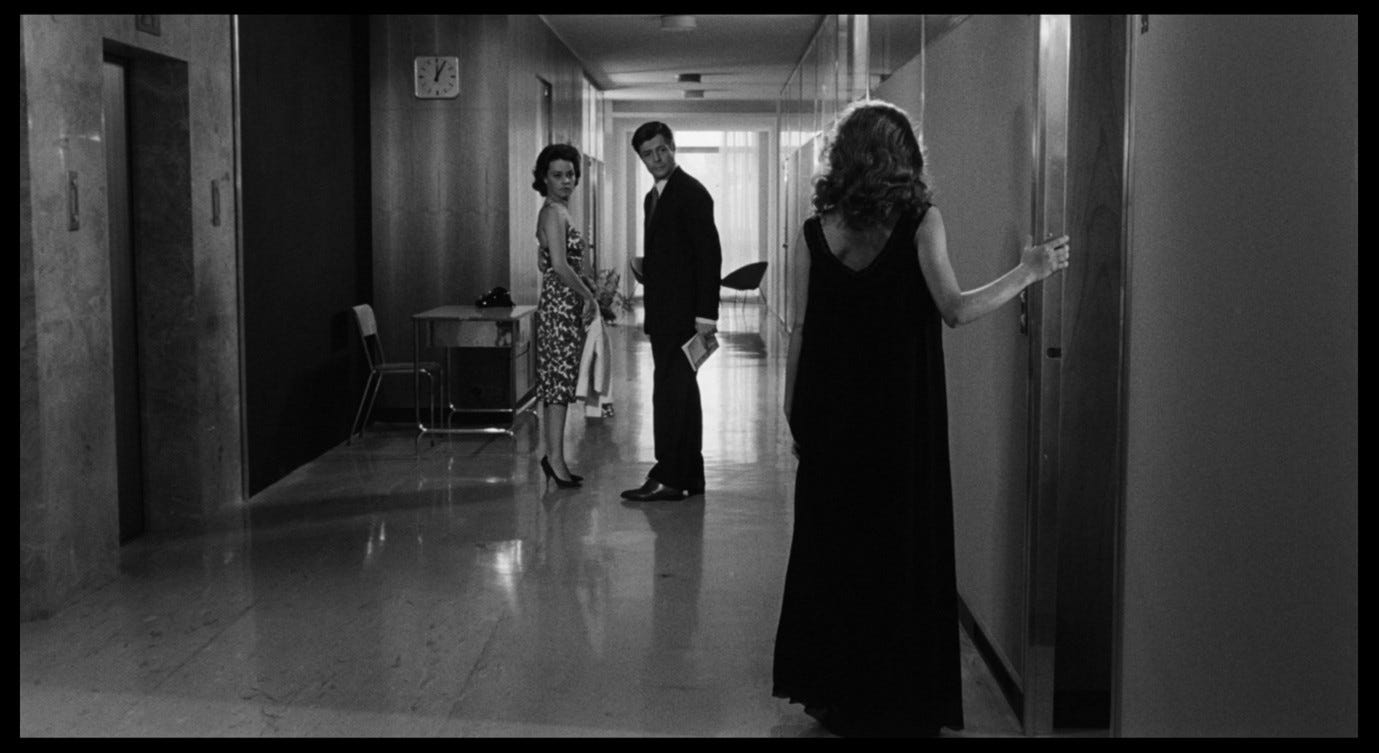

The disturbed woman in La notte was also framed against an annihilating white wall, in a hospital whose de-humanising effects are memorably described in the screenplay:

Almost monstrous in its perfection, it evokes the picture of flawless and implacable science… [The awkward elevator ride is] made even more uncomfortable by the impersonality of the décor… Lidia and Giovanni step out of the elevator into a long, cold, highly polished corridor, where the sound of their steps is deadened by the polished rubberised floor.13

In Giuliana’s home in Red Desert, the few objects that stand out against the whiteness are hardly conducive to a homely atmosphere. The light-blue metal railing is the same colour as that ominous tank in the factory, and generally reminiscent of the factory’s colour-coded pipes.

It blends seamlessly into the blue wall outside Valerio’s bedroom, just as the beige door blends into the beige carpet.

The scene is illuminated by an overhead light whose shade is a metal box with a grill on each of its four sides – like the grill in the air-vent that blew on Giuliana’s hair, or the one we looked through to spy on Ugo and Corrado.

The windows, as mentioned above, look out into pitch-darkness (later, in the daytime, they will look out onto the inescapable shipyards). Two pieces of comically out-of-place antique furniture occupy the landing. One is a chest of drawers topped with a decorative display of artificial plants.

Victoria Kirkham explains the cultural significance of the other:

The most striking, and surely the most incongruous, is an antique wooden chair on the landing in an otherwise aseptic stairwell […] In both English and Italian, it is known as a ‘Dante chair.’ From a similar chair, Dante presides in Giorgio Vasari’s often copied Portrait of Six Tuscan Poets of 1544, [pictured below14] perhaps the origin of the term. […] [It is a visual allusion to] a past nearly obliterated by the all-encompassing present.15

These pieces of furniture, especially the Dante chair with its cultural ties to Ravenna, are efficient indicators of wealth and taste, carefully positioned so as to create an effect without cluttering this ultra-modern home. As Kirkham says, their placement connotes their displacement, their obsolescence. Angela Dalle Vacche describes them as ‘a few precious, old pieces set amid rather barren, pristine white walls,’ but also, significantly, as ‘collector’s items that spell out the economic power of a social class used to purchases from antique dealers.’16 Everything in this space is functional and limited. There are precisely the right number and combination of colours, precisely the right amount of light filtering across the landing, and precisely the right kinds (and numbers) of objects.

This painting on the wall (Rite of Spring [Sagra della Primavera] by Gianni Dova)17 is also, somehow, precisely right.

Like the mural in the factory (discussed in Part 7), it is a carefully placed work of modernist art that reinforces bourgeois power structures.

Somehow, the juxtaposition of the antique furniture and Dova’s abstract expressionism, within the context of this clinically perfect home, conveys the intended message about the space and the people who inhabit it. Whether we detect more of Ugo’s design or of Giuliana’s in the decoration of their home will depend on a number of factors, and on our own preconceptions. For me, the domestic scenes in this film tend to stress Ugo’s complacency and Giuliana’s discomfort, so it seems like an environment that has been constructed and defined primarily by him. ‘None of Antonioni’s characters ever seem at home,’ says Sam Rohdie; ‘They are on the move, in houses which belong to others or appear to belong to others.’18

Dova’s Rite of Spring is also juxtaposed with other works of art. As Giuliana gets out of bed, we see Valerio’s paintings stuck on her wall.

We have a few seconds to look at these before a cut replaces the uppermost painting – an incomprehensible daub of blue and yellow streaks – with Dova’s painting (which also features dominant blues and yellows) in the same position in the frame.

I will say more about these artworks in Part 11, but for now it is enough to observe the highly decorous placement of the child’s paintings in the bedroom – keeping them private while stressing how much they are valued by his parents – and the expensive abstract painting in the more visible wall-space over the stairs, where it can be seen and appreciated by visitors. Somehow, it would not be fitting to place Valerio’s paintings beside Dova’s, or to place the Dante chair directly below a piece of modernist art.

Somehow, equally, it is not surprising that Giuliana feels uncomfortable in her own home. If everything, every object and colour-tone, has an exact place and function, where does she fit in? This sequence is almost a dramatisation of a passage from Hermann Broch’s The Sleepwalkers (the novel Valentina is reading in La notte), in which one of the characters finds herself inexplicably alienated from the décor in her own home:

It had given her a great deal of labour and pleasure to find for every piece of furniture its appropriate position, so that a general architectonical equilibrium might be inaugurated; and when all was finished Hanna Wendling had the feeling that she and she alone was aware of the perfection of that equilibrium, even though Heinrich too had a share in the knowledge, even though a great part of their married happiness consisted in this mutual awareness of the secret harmony and counterpoint exemplified in the arrangement of the furniture and pictures. Now the furniture had not been moved since that time, on the contrary, strict care had been taken not to alter the original arrangement by an inch; and yet it had become different: what had happened? can equilibrium suffer depreciation, can harmony become threadbare? […] [T]he curse of the fortuitous and the accidental had spread itself over things and the relations between things, and one could not think out any arrangement that would not be just as fortuitous and arbitrary as the existing one. […] So Hanna Wendling walked through the house, walked through her garden, walked over paths which were laid with crazy-paving in the English style, and she no longer saw the pattern, no longer saw the windings of the white paths.19

Certain characters in Antonioni’s 1960s films – especially from L’eclisse to Blow-Up – often seem to be pursuing something like the ‘perfect equilibrium’ that Broch describes, filling their homes, professions, and personal lives with just the right decorations, gestures, and people to create the desired effect.

If equilibrium is the ideal being sought, it is no wonder that Giuliana is so afraid of over-heating, a cardinal sin in this cool, measured environment. Hanna Wendling, in The Sleepwalkers, sees the equilibrium of her home being infected with a sense of ‘arbitrariness’, as though all the ordered structures of her life were disintegrating into chaos. Giuliana moves from place to place, and positions and re-positions her body and its limbs, with a restlessness that echoes Hanna’s.

The rules governing how she is ‘supposed to’ occupy her home no longer make any sense; they have become arbitrary, nonsensical, and no one else seems to have noticed. Her spasmodic gestures are not only reflex-responses to her inner pain, they are also a frenzied attempt to find the ‘right’ gestures and positions, to occupy this space in the way she is supposed to. Giuliana’s repeated reconfiguration of her limbs reminds me of Buster Keaton in Our Hospitality, trying to position himself appropriately in a household that is trying to kill him.

Again, it is important to emphasise that the instability is not just within Giuliana herself, but in the world around her. This is apparent in the imagery of the nightmare she recounts to Ugo:

I dreamt that I was in bed, and the bed was moving. Then I looked and I saw that it was resting on quicksand [sabbie mobili]…and it went down…always further down…

Giuliana dreamt of being in the place where she in fact was – her own bed – and it was the bed, with her in it, that sank into the shifting sands. The image of quicksand (literally ‘moving sands’ in Italian) recalls the seething waste of the slag-heap that so frightened Giuliana the previous day, but the idea of being swallowed up by one’s surroundings also recalls the world-eating steam-cloud in the factory courtyard.

As well as being sterile and functional, Giuliana’s world is also (paradoxically) nebulous and unpredictable, and her dream shows her awareness of this.

It is significant that the dream involves a descent and that Giuliana emphasises this with the repetition of ‘down, always further down.’ This fear of what lies beneath is related to her fear of the ground floor. Perhaps that descent into an unknown darkness felt too much like the descent into quicksand from which she had just woken up, hence her retreat from the stairs to the landing. Later, Giuliana will describe the falling/sinking/drowning sensation to Corrado in similar terms, again repeating ‘down, down.’ In the context of the present sequence, especially given its association with the marital bed, Giuliana’s fear seems rooted in her immediate domestic environment, not unlike Karin’s fear of the God-like/father-like spider. Clearly, it is not just the hazards and pollutants of the factories that threaten Giuliana, but something more pervasive in the world she inhabits.

Next: Part 11, Familial terrors.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 442

Godard, Jean-Luc, ‘The night, the eclipse, the dawn’, trans. Andrew Taylor, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 287-297; pp. 290-291

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 442

Forgacs, David, ‘Antonioni: Space, Place, Sexuality’, in Spaces in European Cinema, ed. Myrto Konstantarakos (Exeter: Intellect, 2000), pp. 101-111; p. 105

Forgacs, David, ‘Antonioni: Space, Place, Sexuality’, in Spaces in European Cinema, ed. Myrto Konstantarakos (Exeter: Intellect, 2000), pp. 101-111; p. 108

King James Bible, 1 Corinthians 13:12 (BibleGateway.com)

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 55

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 185

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 101

Jacobs, Steven, ‘Between EUR and L.A.: Townscapes in the Work of Michelangelo Antonioni’, in The Urban Condition: Space, Community, and Self in the Contemporary Metropolis, ed. the Ghent Urban Studies Team (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 1999), pp. 325-342; pp. 339-340

Moravia, Alberto, ‘The American Desert’, trans. Carmen Di Cinque, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 298-303; p. 301

Kinder, Marsha, ‘Zabriskie Point’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 304-312; p. 307

Antonioni, Michelangelo, Ennio Flaiano, and Tonino Guerra, ‘La notte’, trans. Roger J. Moore, in Screenplays of Michelangelo Antonioni (London, Souvenir 1963), pp. 209-276; pp. 211-212

Vasari, Giorgio, Six Tuscan Poets (1543-1544), Minneapolis Institute of Art

Kirkham, Victoria, ‘The Off-Screen Landscape: Dante’s Ravenna and Antonioni’s Red Desert’, in Dante, Cinema, and Television, ed. Amilcare A. Iannucci (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), pp. 106-128; p. 118

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 56

Dova, Gianni, Sagra della Primavera (1961), Collezione Ghigi-Pagnani. Image from ArtsCore. I identified the painting through a Google Image search.

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 141

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers, trans. Willa and Edwin Muir, 1947 (New York: Vintage International, 1996), loc. 7188-7217 (Kindle edition)