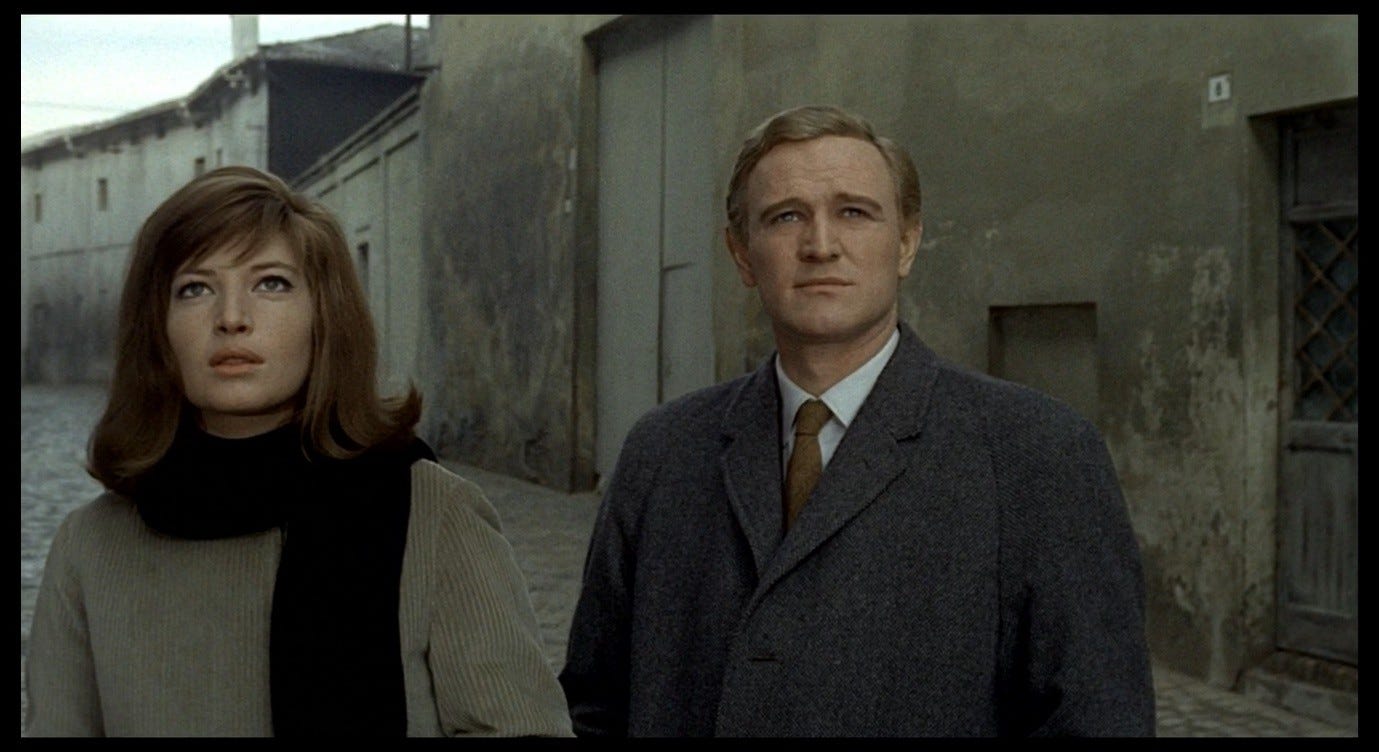

If Giuliana’s surroundings feel suffocatingly modern in the early scenes of Red Desert, it may come as a relief to see her, as we do now, in an older part of Ravenna, among buildings where the telegraph wires stretching between roofs are the only signifiers of the 20th century. Indeed, according to Google Street View, the Via Pietro Alighieri looked quite similar as recently as 2020 (bearing in mind that it was made artificially grey for the film).

This is where Giuliana is trying to set up her shop, and where her relationship with Corrado will begin and end.

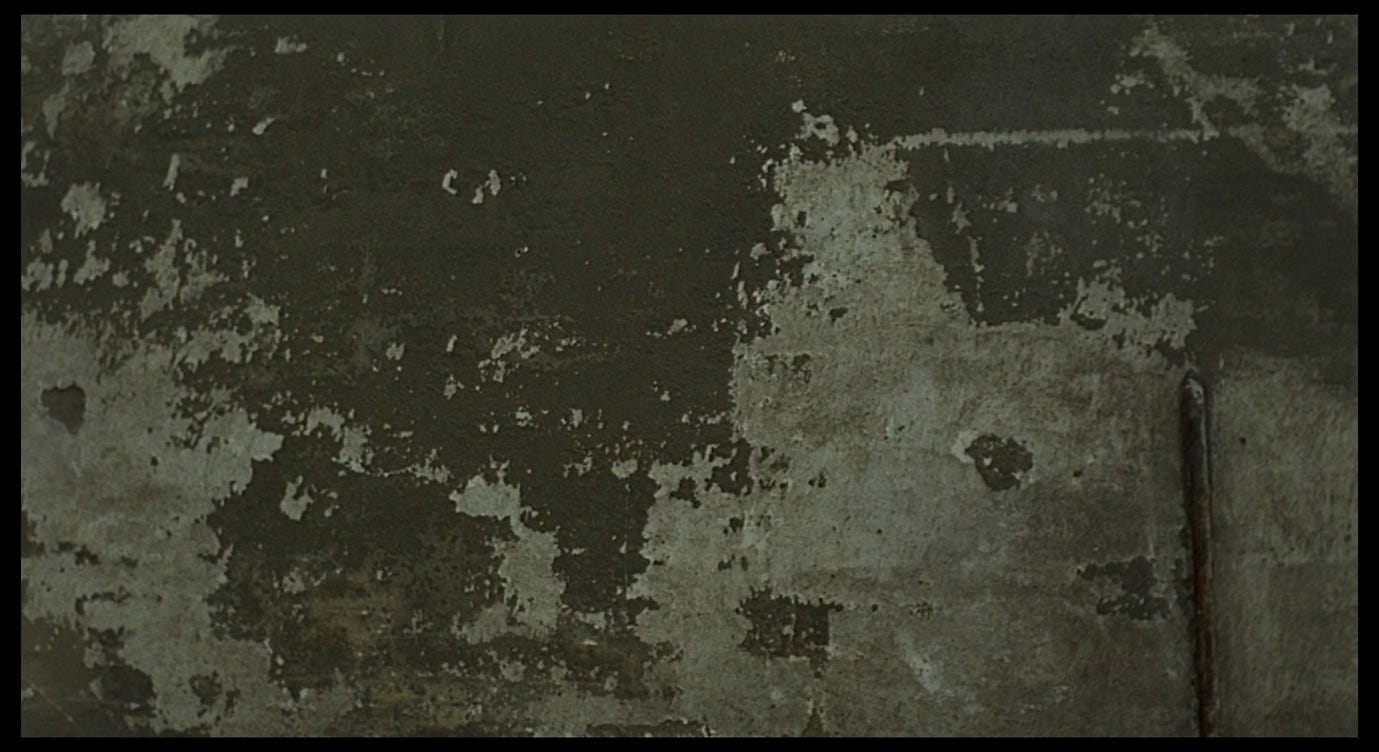

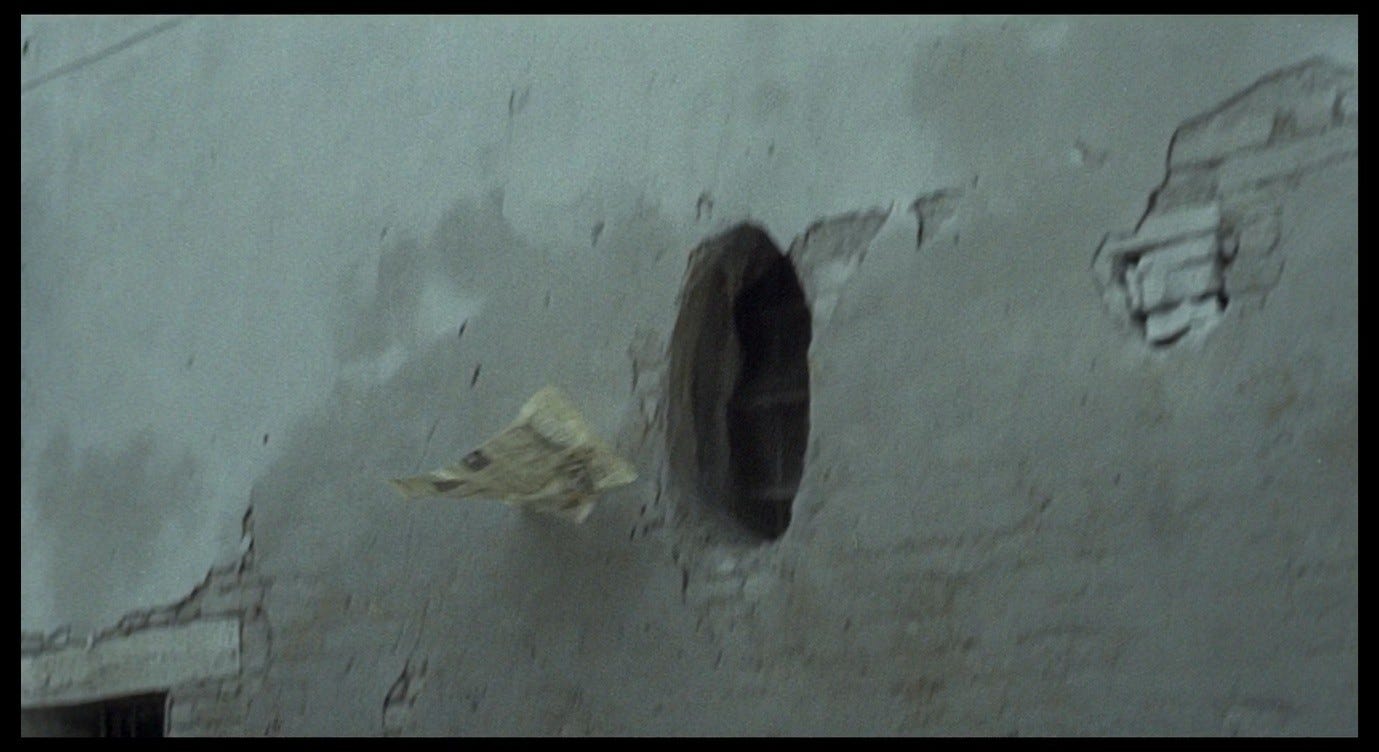

The final image of the previous scene – of two heads framed against the out-of-focus Rite of Spring – cuts to a perfectly in-focus image of a wall, although it may not be immediately obvious what we are looking at.

Sam Rohdie notes that there are several such moments in Red Desert: ‘only retrospectively do things reveal themselves […] when a figure or object enters into that space or along its surface to form a relation which identifies it.’1 If we are (even unconsciously) searching for patterns, we may see a vague echo of the space occupied by Ugo and Giuliana in the dark and light blotches in the lower part of the frame. Their heads have been flattened into the painted surface of Dova’s canvas, whose colourful, fantastical imagery has in turn metamorphosed into this dull greenish-grey wall. Or perhaps we think this is an even more challenging piece of abstract art. As in the previous image of the painting, blurred beyond recognition, the film is playing with our perceptive and interpretative faculties, and in that sense is giving us another glimpse of the world through Giuliana’s eyes. If she has to deal with a reality that is constantly on the verge of dissolving, where places, people, and objects lose definition, then so (occasionally) do we.

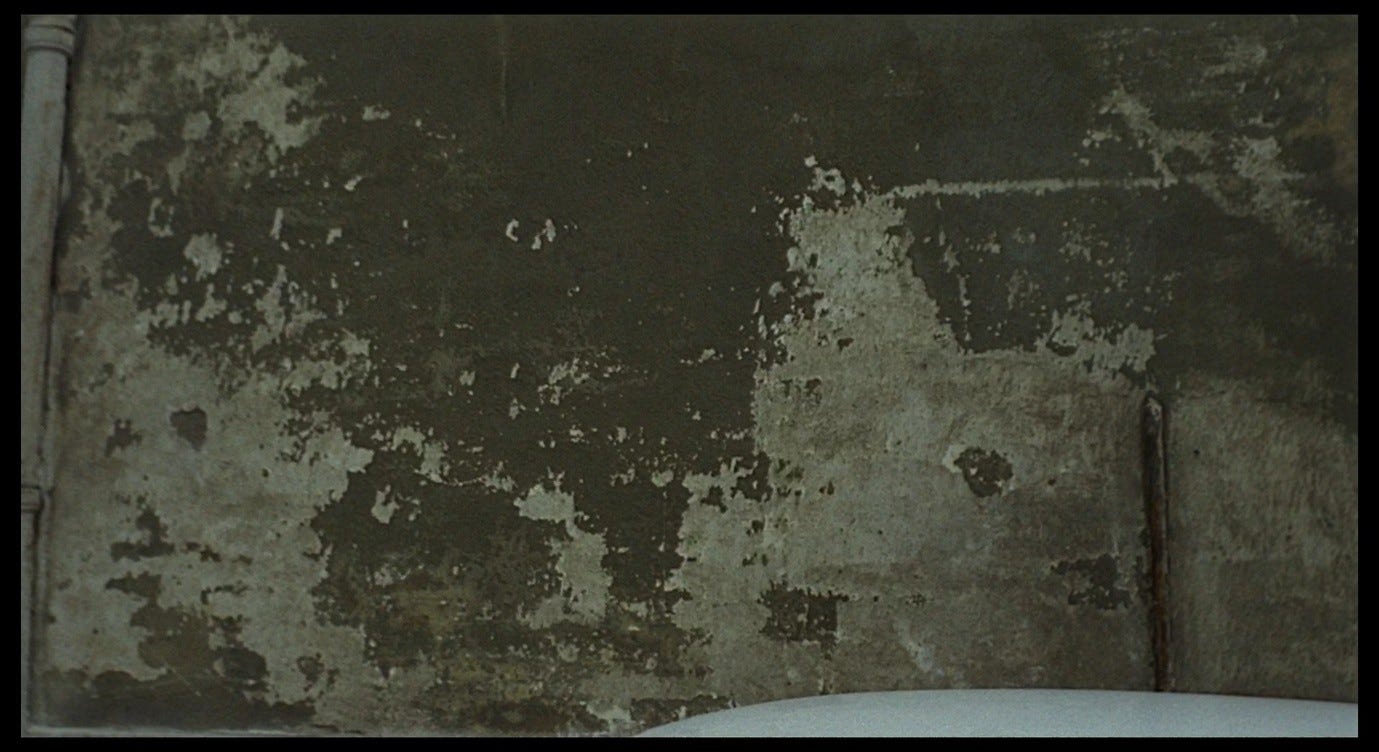

Having said that, after our initial disorientation we probably see the pipe in the right-hand corner of the image, and infer that this is indeed a wall. As the camera dollies back, an even bigger pipe confirms this, as does the positioning of the window on the left and the roof of Corrado’s car at the bottom of the frame.

Corrado could have parked in front of the pipe-less stretch of wall we see to his right in this shot:

and we would have had even fewer clues to the identity of this surface. As in the factories, we get a sense (again, unconsciously) of how pipes communicate the nature and function of a space.

The film is pulling off a familiar trick, making us feel disoriented and confused like Giuliana, then granting us a well-oriented perspective that can interpret the environment with relative ease. But Rohdie argues that this establishing shot maintains a sense of disorientation, even after the ‘clarification’ that occurs when we step back from the wall:

[F]iguration itself is suspended, the entire volume and depth in which things take place in narratives seems momentarily absent and in its place appears the ‘emptiness’ of a surface image, unmoored, unidentifiable, narratively blank, a kind of eclipse of narrative into abstraction. The wall materialises out of nothing both narratively and visually, but when it does its other status as image remains: while one part of the pressure of the scene is towards the construction of ‘facts’ […] another part of the scene moves towards dissolution, nothingness.2

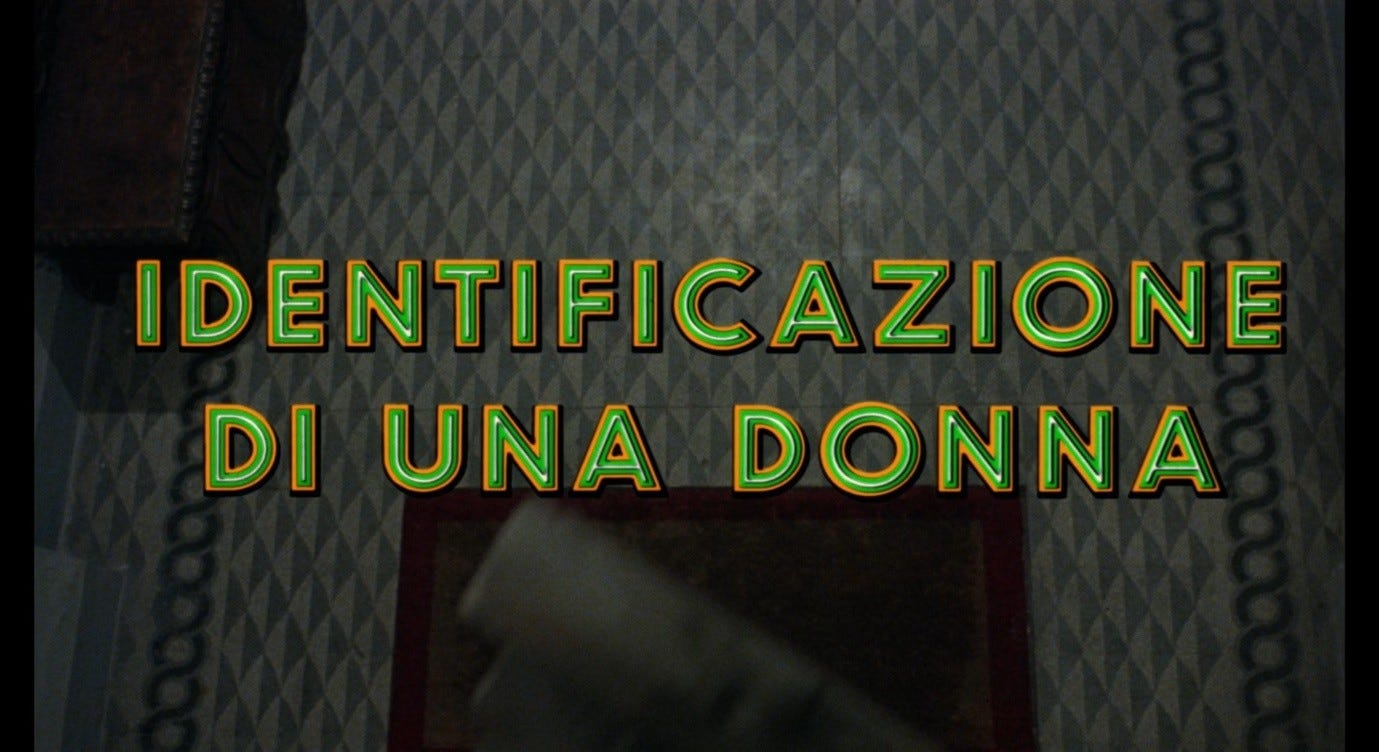

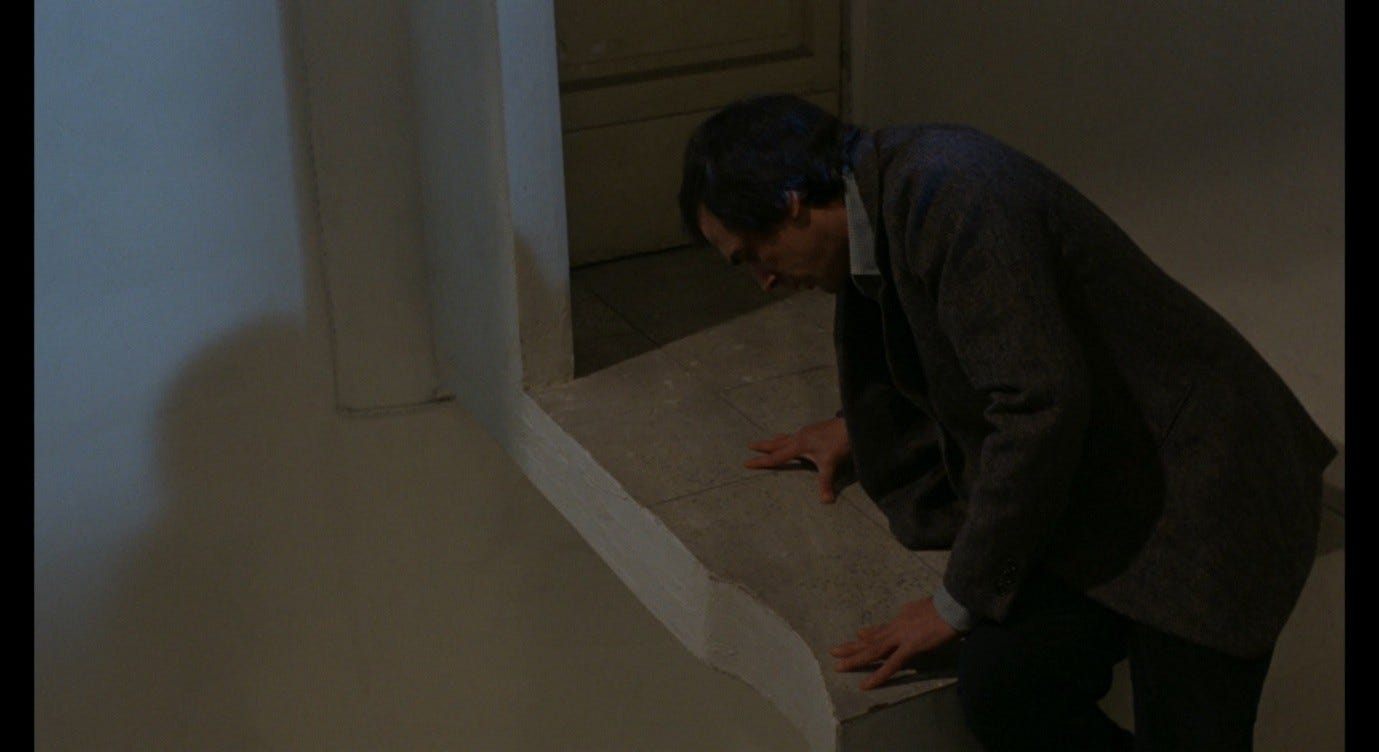

A similar effect is achieved in Identification of a Woman, also photographed by Carlo di Palma. Identification begins with an image of a more-or-less flat surface covered with shapes of different colours.

We may not realise what we are looking at until the door opens and Niccoló’s suitcase, then the crown of his head, enter the frame.

This is an overhead shot of the hallway in his apartment building. In those first few seconds, making sense of the image is a little like trying to make sense of Gianni Dova’s Rite of Spring. At first glance, the doormat at the bottom of the frame looks more like a chest of drawers than the actual wooden chest that is relegated to the top-left corner, because it is the same shape as a chest normally is when we look at it head-on, and because it is at the bottom of the frame (as though it were positioned on the floor). But then we notice that this rectangle dominating the centre of the image is flattened against the background, whose patterned tiles – diamond shapes, each evenly divided between light and dark, with serpentine black spirals on either side – are designed to create a false three-dimensional effect. We can see just enough of the walls at the edges of the frame, and of the chest in the corner, to get a sense of ‘proper’ perspective, but like the drainpipe in Red Desert, these clues are marginalised to prevent us from noticing them right away. We are given a moment to experience that fleeting sense that we are facing a wall, so that when we re-identify the image as ‘floor’ we will feel the mild sense of doubt and anxiety that is the defining mood of the film.

In a famous moment towards the end of Identification of a Woman, Niccoló will look down at Mavi – the primary object of his identificatory efforts – from the same overhead perspective, unseen by her at the top of a spiral staircase (built specially for the film).

Whereas his hallway looks geometrically ordered and coherent from above, in Mavi’s building this perspective shows a vertiginous abyss. The tiles and spiral shapes in the hallway created a mild, aesthetically pleasing illusion of depth, but now Niccoló stares down into an actual spiral filled with actual alternating light and shade, a depth into which one could fall and die. Later on, another woman, Ida, will explain she is leaving Niccoló to be with another man who is her ordine (‘order’), the person with whom her life will make sense. Niccoló goes back, somewhat ruefully, to his own ordine in his apartment. From the start of the film, through its title and its gimmicky opening shot, these themes of order and disorder, mystery and sense-making, are foregrounded. The context is very different from Red Desert, but the search for an ‘ordering’ or ‘identifying’ perspective on the world is woven through both films.

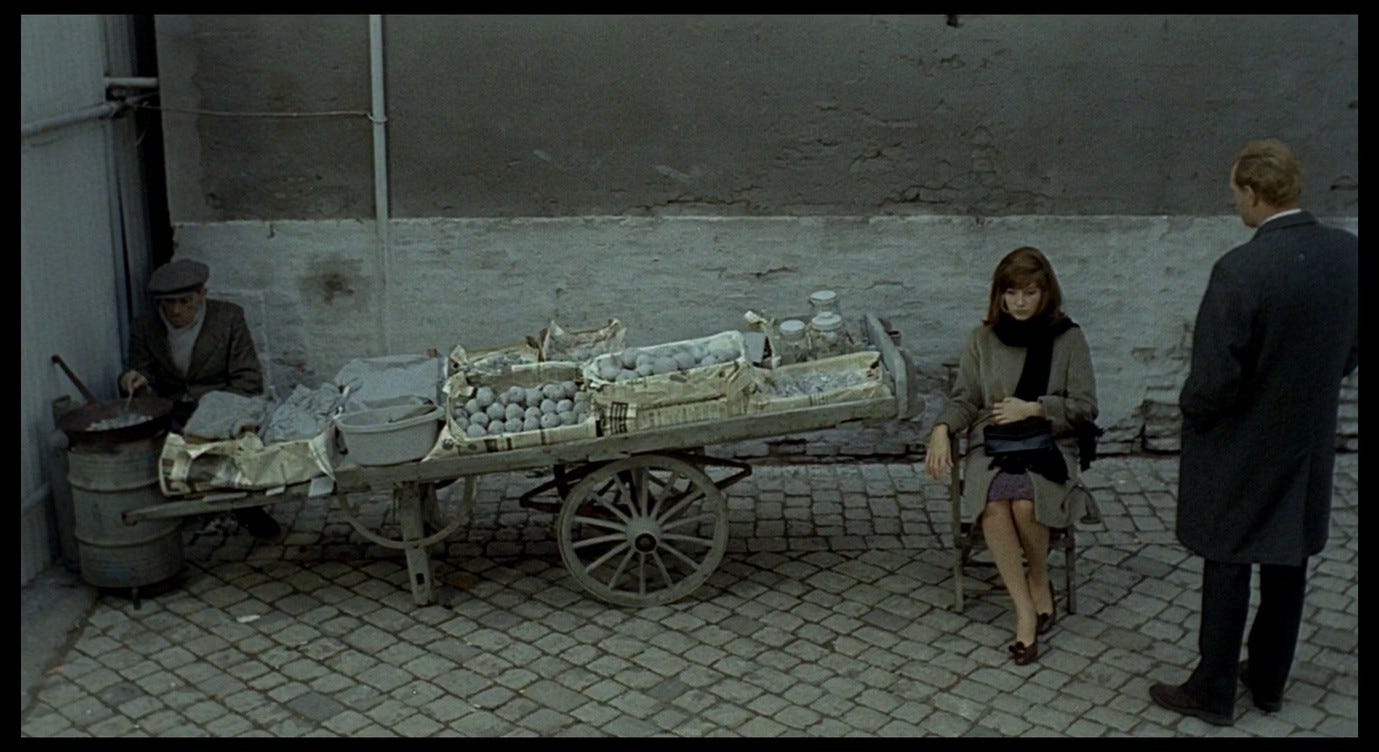

One thing we may identify about the wall (and the pipes) in Red Desert is their dilapidated state, which had clearly been improved upon by 2020. The setting for this sequence is archaic, desolate, and de-populated. Only three people besides Giuliana and Corrado appear in the street: a man on a bicycle, a woman knocking on a door, and the fruit-seller. During the scene in Giuliana’s shop, we also hear a horse-drawn cart passing by outside, its bell tinkling.

Notice the distinctive round arch over the door the woman knocks at on the left-hand side of this shot:

Thanks to another Google Street View image, we can see that the woman is visiting the convent of the Capuccine Clarisse nuns. Here is the view from the other end of the street:

According to an undated webpage, the convent was established in this location in 1823 and was, as of (presumably) quite recently, presided over by an abbess who joined the convent in 1956. There is nothing in the present scene in Red Desert to tell us this is a convent, and only someone who knew this street well would be able to identify it as such, but I think it is significant that Antonioni directed this background extra to knock on this specific door. We sense that this woman, and the visit she is paying (whatever its motive), are from a sphere of existence that would be quite alien to Giuliana, Ugo, and Corrado.

The few (visible or audible) human figures in this scene embody archaic modes of transportation, communication, commerce, and social connection, but more conspicuously they evoke the loneliness of this street. The woman visiting the convent does not appear to receive a response; after knocking at the door, she stands back and looks up expectantly at the windows, perhaps hoping for signs of life.

The extras in this scene do not interact with each other or with anyone else, unless we count the strange, hostile look the fruit-seller gives Giuliana. We are looking at a decaying remnant of the past that has somehow been preserved despite being drained of all life. (To be clear, this is how the street is presented in the film, not necessarily how it is in real life.)

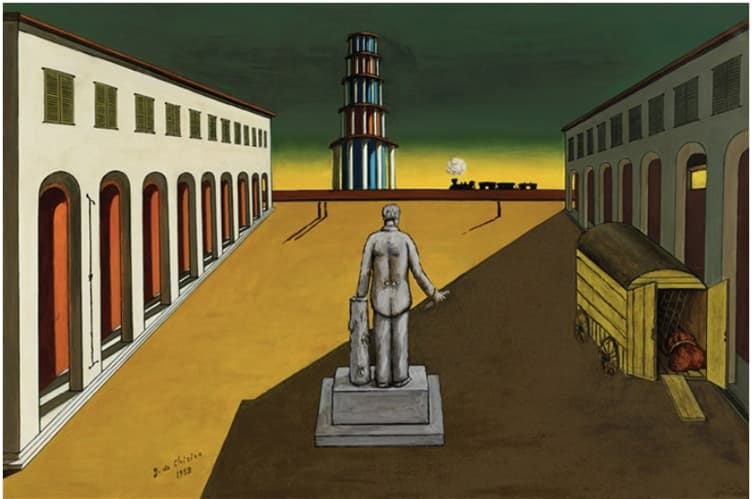

Angela Dalle Vacche cites this sequence to illustrate the influence of Giorgio de Chirico on Antonioni, particularly insofar as Antonioni uses de Chirico-like imagery to portray the ‘clash of old and new.’3 This sequence, Dalle Vacche argues, ‘looks like a whole canvas by de Chirico,’ with its deserted, claustrophobic street and its self-absorbed human figures.4 She cites de Chirico’s anecdote of being inspired, while recovering from an illness, by an empty square that seemed to him to be ‘convalescent’, and she connects this with a long cultural tradition of associating creativity with pathology:

[T]he scenario of convalescence at the heart of Red Desert not only fits the theme of artistic creativity for the director and of attainment of a new sense of self for the female protagonist, but it also intertwines with the need to clear the ground, to start with a tabula rasa, to produce a temporary void, which is typical of traumatic historical change and melodrama.5

Giuliana is in an ongoing process of recovery from (or relapse into) an illness, and like de Chirico she is drawn to blank, empty spaces that offer a possibility of renewal. Dalle Vacche’s references to both historical change and melodrama are pertinent to Red Desert, in which the struggle to adjust to modernity is inextricably linked to the development of an adulterous affair. The concept of the ‘nuova avventura’ (discussed in Part 11) is linked to the renewal of self, the ground-clearing, and the temporary void that Dalle Vacche includes among the pursuits of the convalescent-creative.

Although Antonioni said that he did not deliberately imitate painters in his films, Matilde Nardelli too argues that

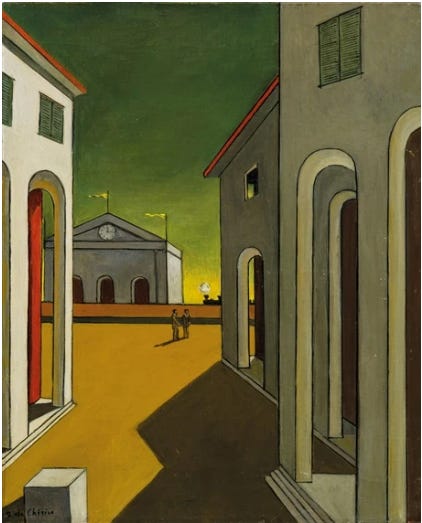

De Chirico’s ‘pittura metafisica’ of nearly empty townscapes […] seems undeniably evoked in the very way in which the director captures and works on (even if only through framing, angle and lens used) a location he finds, such as the modern, yet abandoned Sicilian village [Schisina] in L’avventura, or the Via Pietro Alighieri in the historic centre of Ravenna in Il deserto rosso, whose pavement and buildings, moreover, were painted white and filmed with blue filters on the camera lens so as to appear greyish.6

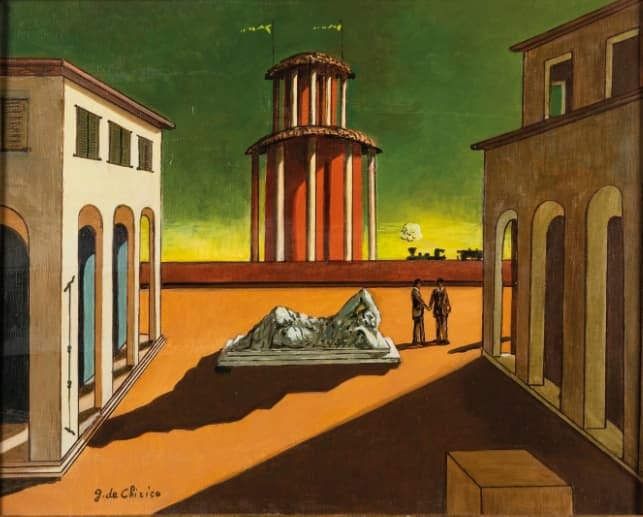

In Antonioni’s re-painted version of the Via Alighieri, the contrast between the light grey of the left side of the street and the darker beige of the right side echoes the stark light/shade contrasts of de Chirico paintings such as Piazza d’Italia, 1963.7

The cyclist perhaps recalls the girl with a hoop from Melancholy and Mystery of a Street.8

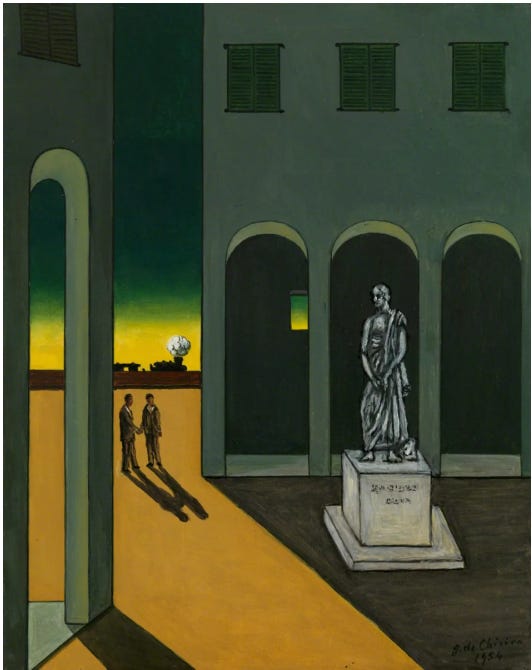

Giuliana and Corrado stand out like the paired figures who sometimes appear in de Chirico’s paintings: for instance, the two men who meet in an empty square, one looking in another direction while the other shakes his hand, in Piazza d’Italia, 1970.9

Another entry in the Piazza d’Italia series resembles the famous unmotivated dolly shot in L’avventura in the scene just referred to by Nardelli, when Claudia and Sandro visit the deserted village of Schisina. Like that camera movement, de Chirico’s painting evokes the sense of prowling down a dark, empty street towards a square with a dominant (but still empty) building looming over it.10

In Sgombero su piazza d’Italia, 1968, two figures (too small to have identifiable features) stand side by side, while a lone figure stands some distance away on the other side of the picture; the figures are identical and cast identical shadows.11

This kind of couple/single juxtaposition is especially evocative of Antonioni, contrasting an image of ‘togetherness’ with an image of ‘solitude’ but also calling into question the distinction between them. People meet without interacting, are together without relating to each other, and are somehow both coupled and alone, rather than alternating between these states.

Cara Hoffman says that in de Chirico’s paintings she found ‘the dream landscape of my childhood and the piazza of my awakening, merged.’12 As a child, growing up in a depressing American town where ‘people did not spend time outside their houses,’ she would imagine she was living in a post-atomic wasteland: if she walked into someone’s home, she thought she would find ‘a skeleton sitting in a La-Z-Boy bathed in the glow of The Price Is Right.’ In Europe, she discovered the beauty of ‘the evening sun setting an empty piazza aglow,’ and returning to America she struggled to recreate this experience:

The closest I came back home to feeling the same kind of powerful and solitary dislocation in the face of beauty was looking at the Bethlehem Steel plant surrounded by snow, while I stood at the top of a toboggan run.13

Hoffman’s article makes me think of Red Desert because it not only distinguishes between the desert space of the Italian piazza and the cultural desert of the modern American town, it also shows how the two eventually bleed into each other through an encounter with de Chirico. The apocalyptic childhood playground contrasts starkly with the old-world beauty of Vicenza, but when Hoffman sees Mystery and Melancholy of a Street, she sees those two spaces merged together, just as she found an echo of the piazza in the Bethlehem Steel plant.

Hoffman describes a lifelong search for the ‘powerful and solitary dislocation in the face of beauty.’ For Antonioni’s characters, this search has less to do with beauty than with communication, but dislocation (in multiple senses) is still of central importance, as it was for de Chirico:

I called [my paintings] ‘metaphysical’ on the basis of the etymology of the word itself. ‘Metaphysical’ means ‘beyond physical things’, and in fact what I thought I was expressing was something that went beyond the tangible, that which directly touches our senses.14

From the outset of the Via Alighieri sequence in Red Desert, we find ourselves in an encounter with something that goes beyond tangible reality. We were just staring at a painting that was, through the blurring effect, no longer a painting; then we found ourselves staring at a wall that seemed, for a moment, not to be a wall, indeed that may have seemed more like a painting. Then, as Corrado gets out of his car and looks quizzically at this desolate place, we immediately pick up on the not-quite-there atmosphere of the setting. Like Hoffman, we might expect to find the houses full of skeletons, or perhaps full of intact persons covered in grey dust.

Seymour Chatman argues that de Chirico’s paintings ‘suggest that the town was once occupied, that the people have gone away and may even return,’ in contrast to the deserted town in L’avventura which ‘looks as if it has never been lived in, as if some intuition warned the Sicilians to have nothing to do with it.’15 But Claudia and Sandro have no access to the historical data about Schisina, which indeed was never inhabited. They have only the empty, echoing buildings before their eyes.

Besides Chatman’s two alternatives – abandoned or never lived in – I think that de Chirico’s paintings and the scene from L’avventura suggest something even more troubling: a town that is not a town, a desert-like reality that lies behind the tangible markers of civilisation. Normally it cannot be seen, but for a moment it is made visible to us. Gilles Deleuze refers to Antonioni’s ‘dehumanized landscapes […] emptied spaces that might be seen as having absorbed characters and actions, retaining only a geophysical description, an abstract inventory of them.’16 The Via Alighieri in Red Desert is like this: a street that is sort-of inhabited, but whose inhabitants have been absorbed and now survive as traces or fossils, grey marks on the grey street. ‘The perspectives seem out of true as in a De Chirico,’ says Rohdie, ‘or the ghost town […] in L’avventura. If this street isn’t there and this town isn’t there, what of its inhabitants?’17

In La signora senza camelie, Clara brings her lover to an isolated waste land from which tall buildings can be seen in the distance – Rome’s EUR district, according to Jacopo Benci.18

This is, as William Arrowsmith says in relation to Lidia’s long walk in La notte, ‘what Italians call la periferia, that is, the neither-nor space where […] city and country intersect in a momentary, fragile equilibrium.’19 Clara tells Nardo that she brought him here

…because I like this place, and because I thought that if two people were here and talking to each other, they would end up understanding each other. But instead…

Clara has escaped to the outskirts of Rome, hoping at the same time to escape the artificiality that is overtaking her life. She is disappointed to find that Nardo sees her, and desires her, as an exotic ‘movie star’. She wants a real connection and hopes that this empty, marginal space will enable such a connection to form. But it does not work. Nardo still talks in the clichés of romantic melodrama. ‘Can you deny this spark between us?’ he asks, trying to kiss her. ‘Don’t ruin everything,’ Clara says, ‘you don’t understand.’ And so they drive away, back into the city.

This moment resonates through all of Antonioni’s films, finding echoes in countless scenes where people seek out deserts of one kind or another in the hope of prompting some special relation or revelation. Noa Steimatsky refers to ‘Antonioni’s grasp of the landscape as a distanced, alienated terrain,’ and calls this a ‘critical, transformative principle’ in his films;20 the desert becomes a way of gaining critical distance from something and thus transforming it. Often, as in La signora, the ‘something’ is a personal relationship. Illicit lovers take refuge in these empty spaces, away from the prying eyes of their social circle, to talk openly about their feelings: think of the Idroscalo in Story of a Love Affair, the embankment in Le amiche, or the plains by the railway track in L’avventura (where Claudia and Sandro make love after escaping from Schisina).

Then these same lovers take refuge in cramped hotel rooms, where they argue.

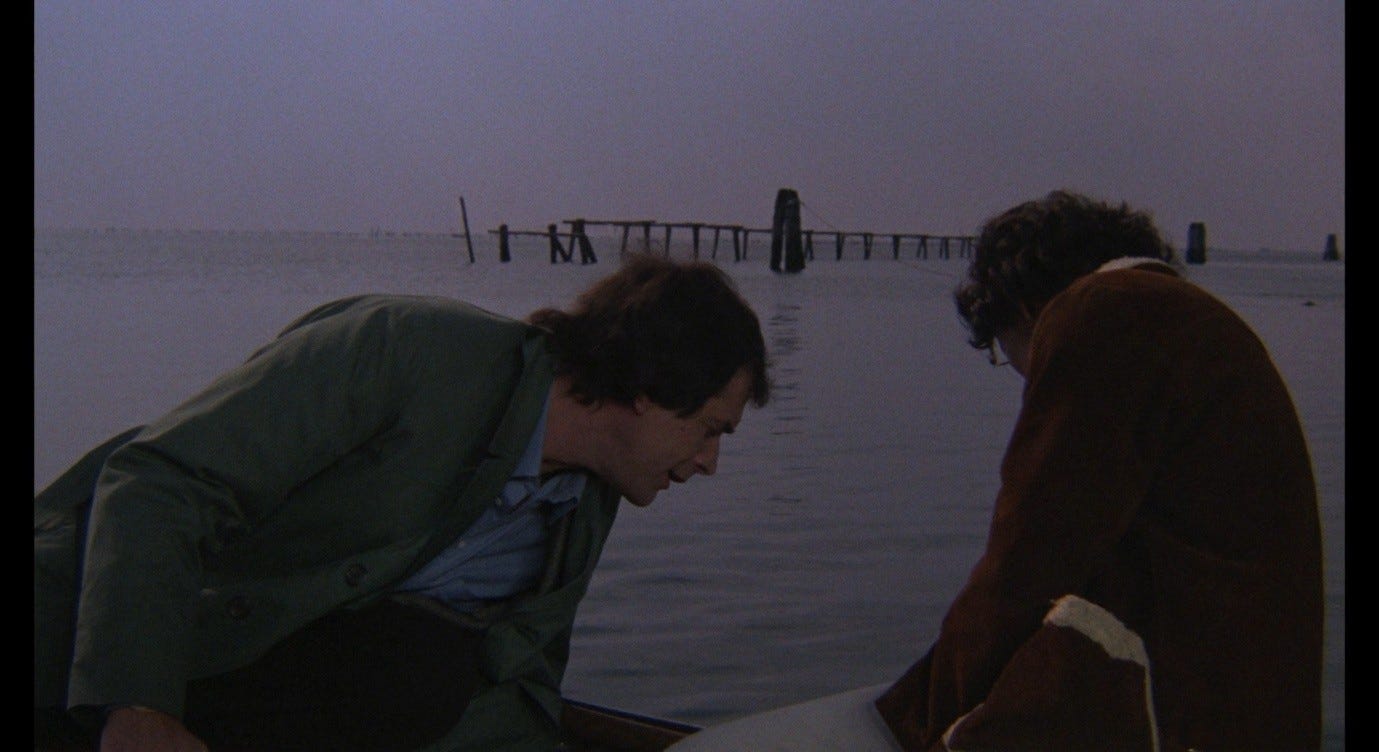

Other Antonioni characters resort to desert spaces to find peace (the park in Blow-Up), to make art (the Venetian lagoon in Identification of a Woman), to commit murder (the parks in I vinti and Blow-Up), or to experience literal or metaphorical death and annihilation (various locations in Zabriskie Point and The Passenger). Beyond Antonioni’s general interest in how people are shaped by environments, he is most interested in how human relationships are affected by being transposed to different spaces, especially empty ones. What does the uninhabited town in L’avventura do to Claudia and Sandro, and why do they run away from it in terror? What do the empty spaces at the end of L’eclisse tell us about the lovers who refuse to appear in them? William Arrowsmith reads David Locke, in The Passenger, in terms which could also describe Clara in La signora:

Inwardly he feels hollow, filled with an emptiness like the desert to which he feels drawn, emptiness to emptiness. […] [L]ike Antonioni’s characters generally, he declares his psychic reality by inserting himself into the apposite geography, a landscape and an emptiness like his own. […] [H]is hunger for transcendence […] draws him toward the desert, itself defined as a waiting, breathing expectancy; it is the desert, or something in the desert, if only a void waiting to be filled, that triggers his adoption of Robertson’s identity.21

Locke is framed against a desert that seems to be waiting for him, and against which he sometimes appears as the more empty vessel. In one shot he is a near-silhouette, pouring water (a transparent substance through which we can see the desert) into his gaping mouth, while the sunlit sand fills the frame around him.

Locke’s adoption of another self is a kind of relationship, just as the emptiness of the desert seems personified as ‘a waiting, breathing expectancy.’ The desert is the new adventure, the new affair, the new self, the empty space in which connection and creation will suddenly become possible. It is striking, for instance, that Locke’s initial odyssey in the desert resembles the rock-climbing search for Anna in L’avventura.

Anna is never found and Locke is stranded in the desert, but in both cases the searchers try to turn this bleak predicament into an opportunity for new adventures. When Locke claws at the sand beside his stalled car, this is both a gesture of despair and a gesture of surrender to the desert elements, in which he wants to bury, cleanse, and renew himself.

However, these adventures are disappointing as well, ending in even bleaker, lonelier dead-ends. In most of the above-mentioned examples, the effort to find a particular kind of connection or way of communicating in a desert space turns out to be futile. The open spaces do not necessarily foster emotional openness, any more than the small hotel rooms foster emotional intimacy. To quote Steimatsky again:

Several of Antonioni’s narratives of failure – most obviously Blow-Up and The Passenger – trace the pitfalls of some such ambition to both partake in experience and achieve at the same time a removed (critical, or non-committal) perspective on the matter at hand. Possibly such attitude is most salient with Antonioni’s male protagonists: it supports one’s reading them as surrogates for the filmmaker, and regarding his attitude to his craft.22

The photographer in Blow-Up thinks he has found stillness and peace in Maryon Park, perhaps a fulfilment of the ambition Steimatsky describes. To partake in experience by being critically distanced from it is a desirable form of relationship, a way for two or more people to ‘end up understanding each other,’ as Clara Manni might say. But the de Chirico-like arrangement the photographer has captured – two figures holding hands while one looks off to the side, with a single figure positioned ominously nearby – turns out to be a premonition of murder, and he becomes inextricably (and inexplicably) involved in this crime.

In fact, the photographer has stumbled into a situation from another Antonioni film: the English episode of I vinti, in which the peaceful setting and the amicable relationship between its two inhabitants turn out to be chillingly ironic. Aubrey’s poetic sensibility and love of beauty have prompted him to bring the sex worker to this spot, but they have also prompted him to murder her; what makes this place serene (it is a desert) also means that no one will see or hear this woman being strangled.

In Identification of a Woman, Niccoló takes Ida to the Venetian lagoon in the hope that their romance will flourish, but when they arrive they find themselves sunk in melancholy. His professional instinct has led him to an excellent filming location, but one that spells the imminent demise of this love affair. It is Niccoló’s ordine to live in such a space, but not Ida’s.

He dips his hand in the water and she drinks some of it. The lagoon is like the desert sand in The Passenger, an element in which one might dissolve oneself. But again, this is the dissolution that Niccoló - not Ida - is seeking.

As in I vinti, La signora, and Blow-Up, the attempt to use a space to achieve a specific goal is strongly associated with the character’s role as an artist. The poet sees everything, even murder, in poetic terms. The actor cannot get away from acting, however distant she is from Cinecittà. The photographer captures the reality in front of him, whether he wants to or not. The director’s romantic getaway turns into location scouting.

In one of his short stories, Antonioni describes a disturbing encounter with a man who seems to be pointing at nothing. The emptiness of the environment is likened to the emptiness of the man’s gesture:

I don’t see anything worth pointing at. At that spot there are neither trees nor those high-tension wires of the sort one sees in the outskirts, there are no telephone poles, no trash barrels, no cars, buses, or people passing. The point is an empty passageway between two buildings, empty of everything but emptiness. The strange thing is this, that you don’t have the sense that at that point the outskirts proper begin, as in fact they do. You have the feeling of emptiness. What the devil is that man pointing at? […] Maybe he’s a lunatic escaped from the asylum […] Or, more simply, one of those people who point to something that only they see.23

The story ends with an inexplicable sense of claustrophobia, a feeling of being trapped between the past and the future, triggered seemingly by that empty passageway and the man pointing at nothing. This is a classic piece of Antonioni creativity, in that it generates art out of nothingness but refuses to frame this as a generative act: you come away feeling depressed and anxious without knowing why.

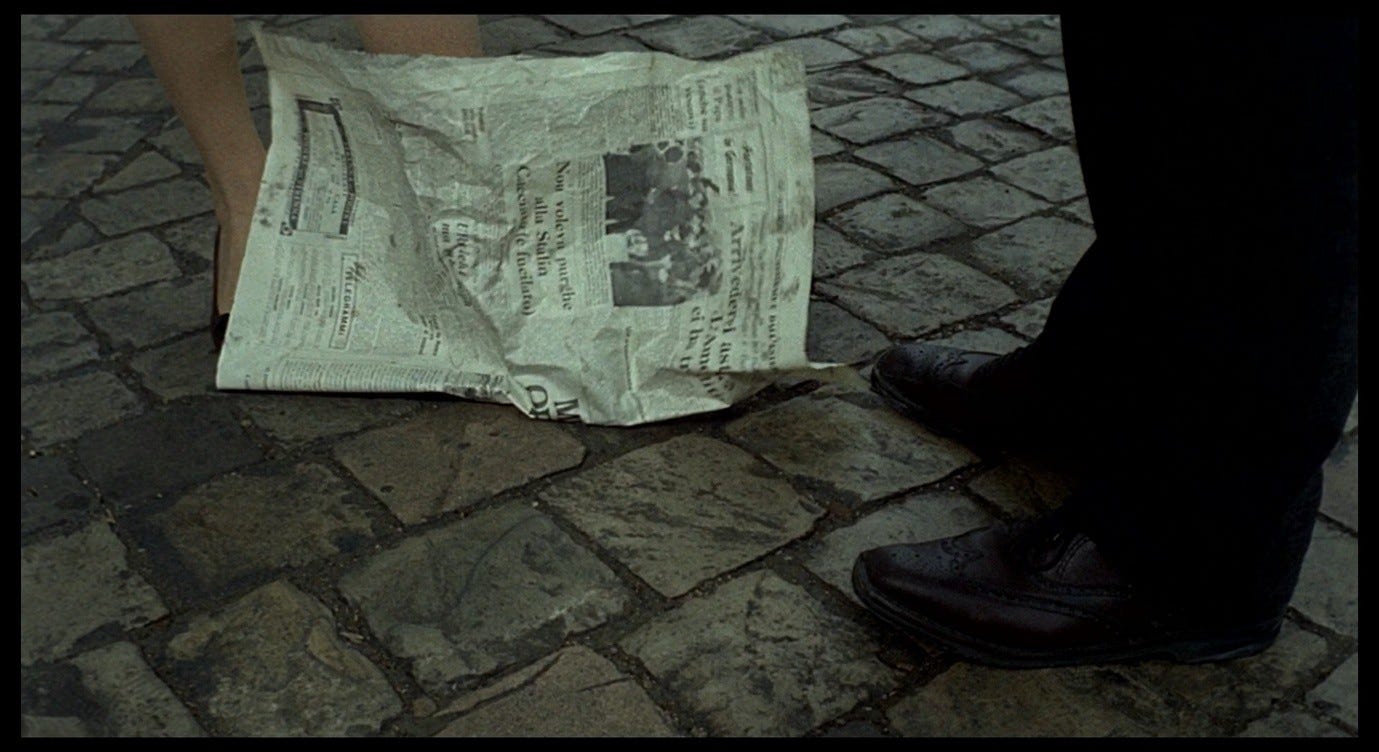

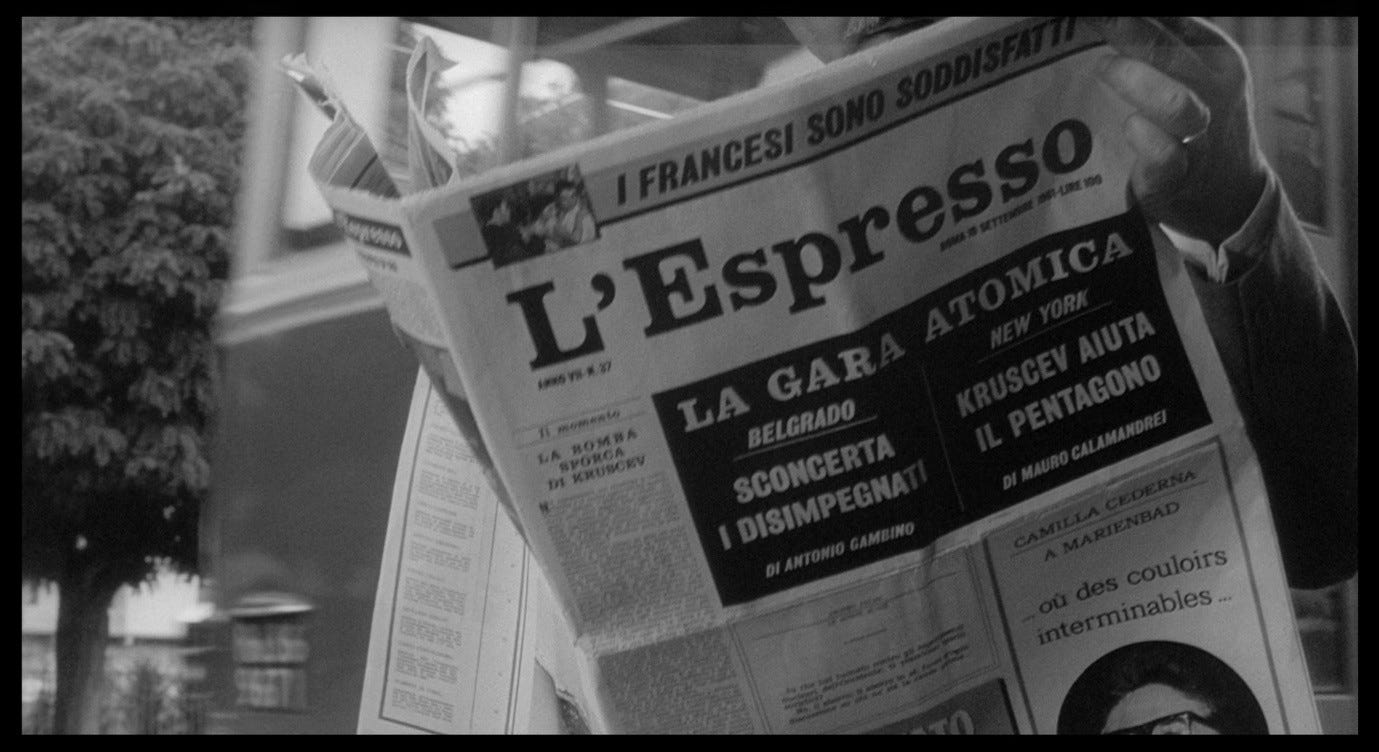

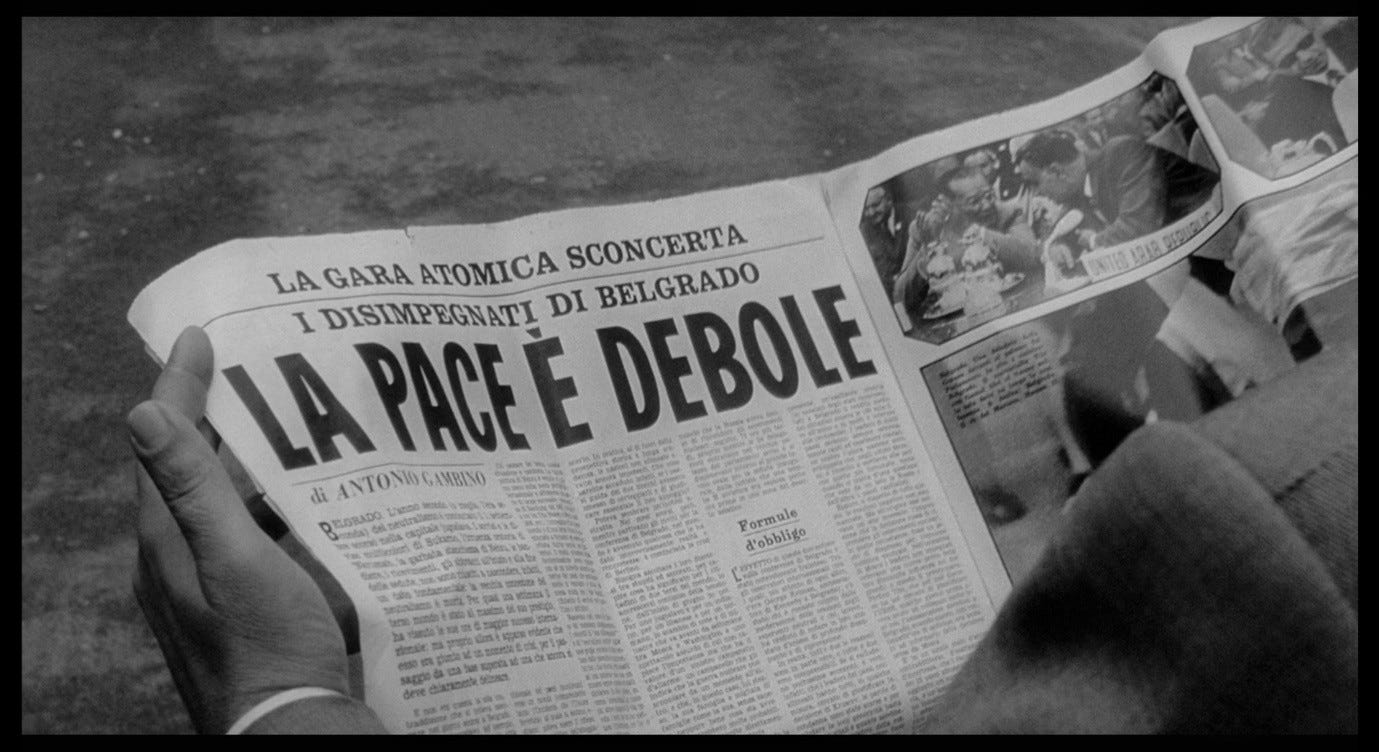

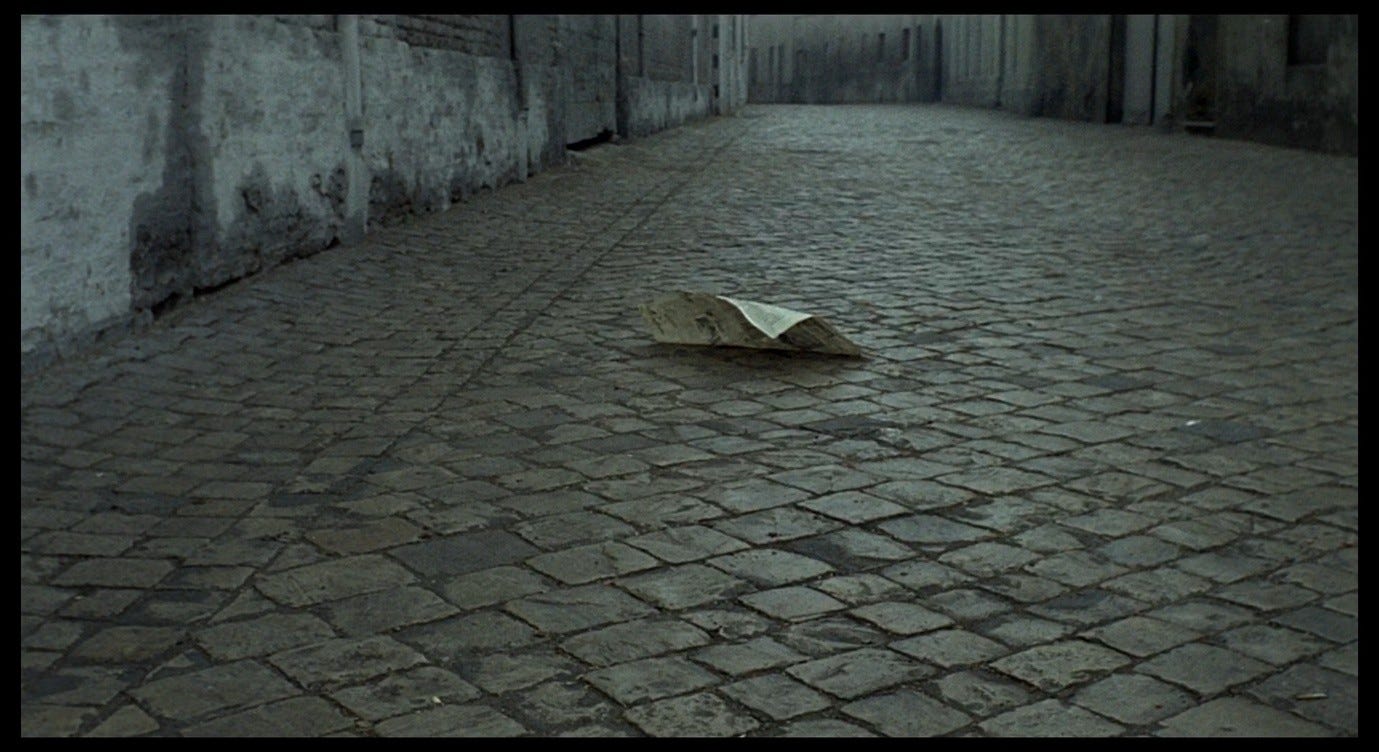

In Red Desert, Giuliana has set herself up in the Via Pietro Alighieri, a street that is named after a 14th-century figure (Dante’s son) and looks like it is stuck in the past. A page from a newspaper drifts down as if from a faraway land, and Giuliana comments, ‘Imagine that [Pensi], it’s from today.’ We briefly glimpse headlines about America and Stalinism, recalling the cold-war tensions alluded to in the newspaper at the end of L’eclisse.

In Red Desert, the present-ness of the paper seems comically misplaced amidst the archaism of the Via Alighieri, as Giuliana acknowledges with her amused ‘pensi’ – who would have thought today’s newspaper would end up here? When she steps on the paper, it flaps up and hugs her foot for a moment, before dancing away and falling dead on the ground.

This recalls a moment during the central ballet sequence of The Red Shoes, when Vicky dances with a newspaper. Entitled ‘Le Jour’ (or ‘The Day’), the paper drifts in and out of the scene, representing both the detritus among which the cursed dancer is forced to wander and the days that pass as she continues her lonely journey through the world. Cut off from the rest of the human race, she briefly imagines that the paper is a man (resembling her fiancé) and that she has found some respite from her solitude, but the man turns back into a newspaper and floats away.

There is a parallel here with Giuliana’s fleeting, disappointing romance with Corrado, and more generally with her sense of alienation from a world whose colours and boundaries seem to shift around her from moment to moment. As in Antonioni’s short story, Vicky feels trapped in an in-between space where she is both compelled to fulfil and prevented from fulfilling her creative impulses: the evil shoemaker is both Lermontov and Craster, art and love, with their irresistible yet irreconcilable demands. Vicky’s journey through dream-like deserts and her lonely dance with the newspaper are ways of visualising the effect of this in-between-ness on her psyche.

Giuliana’s selection of a location as out-of-the-way (both spatially and temporally) as the Via Alighieri, in her attempt to repair her relationship with the world, tells us something about the nature of her predicament. Like other Antonioni protagonists, she approaches this endeavour with a creative sensibility. Like other Antonioni protagonists, she will fail to accomplish her goal. The next time we visit this location, it will be to witness Giuliana’s declaration of all-round failure (and ironic, unwanted success in the field of infidelity). The sense of loneliness and obsolescence in this setting explains both why Giuliana is drawn to it and why she will not find what she needs here. To over-simplify, Antonioni’s characters are drawn to lonely places because they are lonely, and they are drawn to deserts because they have deserted (or feel deserted by) the world. Perhaps they hope to discover a sense of kinship with these spaces, or with the people they bring into these spaces. But they see ‘as if in a mirror, darkly’; the deserts only reflect the characters’ loneliness without soothing it, and only throw into relief their dislocation from other people.

Next: Part 13, The fruit-seller.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 160

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 160

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 51

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 53

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 50

Nardelli, Matilde, Antonioni and the Aesthetics of Impurity: Remaking the Image in the 1960s (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), p. 22

de Chirico, Giorgio, Mystery and Melancholy of a Street (1914). Image from Hoffman, Cara, ‘Vanishing Point’, The Paris Review (06 March 2017).

de Chirico, Giorgio, Piazza d’Italia, 1970, Galerie Andrea Caratsch, St. Moritz. Image from Artsy. The ‘1954’ under de Chirico’s signature reflects his practice of back-dating paintings when reproducing his earlier works.

Hoffman, Cara, ‘Vanishing Point’, The Paris Review (06 March 2017)

Hoffman, Cara, ‘Vanishing Point’, The Paris Review (06 March 2017)

Marchand, Jean José, ‘Interview with de Chirico’, trans. David Smith, Metaphysical Art 11-13 (2013), pp. 286-298; p. 288

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 102

Deleuze, Gilles, Cinema 2: The Time-Image (1985), trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), p. 5

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 175

Benci, Jacopo, ‘Identification of a City: Antonioni and Rome, 1940–62’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 21-63; pp. 44-45

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 52

Steimatsky, Noa, Italian Locations: Reinhabiting the Past in Postwar Cinema (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), p. 38

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 153, 156

Steimatsky, Noa, ‘The Antonioni Screen-Test’, Framework 55.2 (2014), pp. 191-219; p. 207

Antonioni, Michelangelo, ‘Report about myself’, in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), trans. William Arrowsmith, pp. 91-96; pp. 93-94