Everything That Happens in Red Desert (4)

Robotic and human songs

This post contains a spoiler for Forbidden Planet and a vague spoiler for The Conversation.

To complete our exploration of Red Desert’s title sequence, we need to consider the relationship between the two different kinds of music: the robots singing to each other and the human singing to herself. What, if anything, do we make of these songs when we first hear them? On subsequent viewings, how might we read them as foreshadowing the conclusion of Giuliana’s story?

Walter Murch, the celebrated film editor and sound designer, shared Antonioni’s fascination with the soundscape of New York, which I discussed in Part 3. As Matilde Nardelli puts it:

[T]he 10-year-old Murch (who, not incidentally, also spoke of his early interest in musique concrète) ‘capturing the back-alley reverberations of Manhattan’ [in the 1950s] is part of the immediate historical and cultural background to Antonioni’s own record of New York noises.1

In The Conversation, Murch’s sound design takes two human voices and translates them into a haunting electronic babble, set against the non-distorted music and chatter of Union Square in San Francisco. At the start of the film, the camera very slowly zooms in on the square, singling out a mime – who imitates human actions but does not speak – while the electronic ‘ba-da-da-dao’ sounds imitate the speech of two people we cannot yet see.

There is something vaguely sinister about the mime. Like the pod people in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the shape-shifting alien in The Thing, or an evil ventriloquist’s dummy, this entity that follows people around and copies their every move and gesture is existentially menacing. To most people, the mime is either funny or irritating, but to Harry Caul he is a threat. This is not only because the mime draws attention to Harry at a time when he is trying to remain unseen, but also because the mime’s behaviour mirrors Harry’s work as well as his movements. The young couple’s conversation is recorded by being mimicked – reproduced in a distorted form by state-of-the art surveillance devices – and this electronic imitation will then be painstakingly turned back into human speech by Harry to reveal the couple’s secrets, exposing what they are up to just as the mime threatens to expose what Harry is up to. The robotic voices Harry captures are unnerving when we first watch the film, but they are even more so – and in some ways even more inexplicable – when we know how the film will end. The electronic sounds in The Conversation evoke the uncanny terror of perceiving things that we cannot understand, of living in a world that is not legible to our senses. There is something terrible in this garbled chatter, but we will never know exactly what it is.

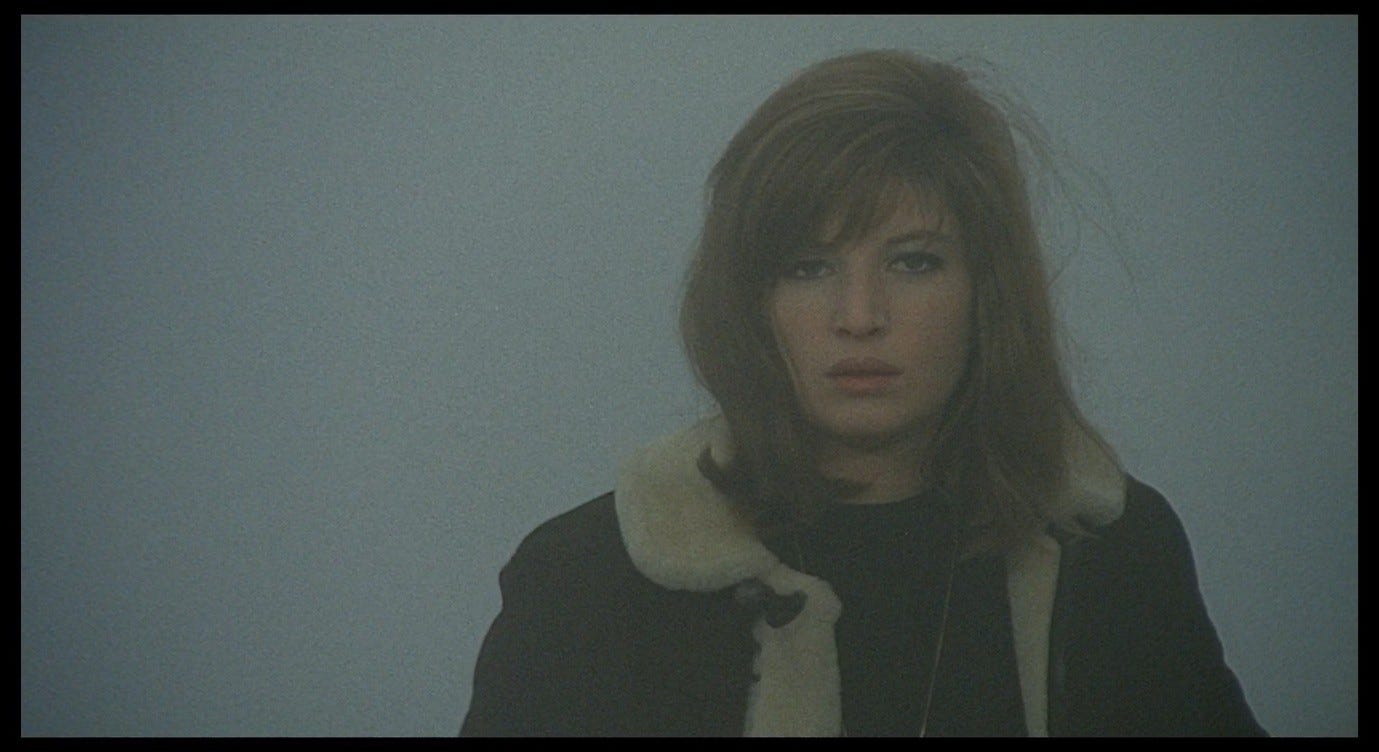

Vittorio Gelmetti’s music in Red Desert evokes the same kind of terror. Giuliana’s position in relation to her world is like Harry Caul’s in relation to his: her environment, her home, and even her own mind and body are sources of inexpressible fear. Both characters are seen getting lost in the fog, lost in a world of indistinct sounds and images, becoming increasingly convinced that there are dangerous powers at work within this fog.

If the phrase ‘red desert’ suggests a world where there are few oases left, red with the blood and flesh of its victims, Vittorio Gelmetti’s electronic effects suggest an aural landscape where even music (Harry Caul’s final refuge) offers no relief. Like the oases, music has been turned ‘concrète’, and the human voice that once inhabited it has become robotic and lifeless. Or worse, not lifeless, but expressive of an emotion or thought that can no longer be accessed through the layers of electronic distortion. What is the Red Desert equivalent of ‘He’d kill us if he got the chance’? What, if anything, are these robots saying?

Literally and figuratively, there are a number of robots in this film, and they represent one aspect of the de-humanising environment Giuliana struggles to come to terms with. The feeling of being surrounded by Stepford People is an integral part of Giuliana’s so-called neurosis. Other people do not seem to be human in quite the same way that she is; they do not seem to see, hear, or feel what she does. In the title sequence, just as the blurred images help us understand Giuliana’s anxieties, so we are also unnerved and disoriented by the voices of the robots, who may be singing to each other, or may be talking to (or conspiring with) each other, or may just be emitting random sounds that result from the practical functions they perform – and those functions might constitute the biggest threat of all.

For a few seconds after the initial ‘vworps’, the robotic song pauses and we hear only the drone of the factories. Then there is a high-pitched ‘niiinnnnng’, then a quick ‘tt-tup, zhoop’. Then, about 50 seconds into the title sequence, there is a short, distant bang like something crashing on the ground…and then at last we hear an un-distorted human voice. As it begins its song, the voice is accompanied by another jarring ‘nninnnng-nniiinnng’, followed by a metallic, echoing ‘ba-da-dang, da-da-ding’ sound. This latter effect is almost identical to the one used in Stalker to accompany the three protagonists’ journey into the Zone on a rail-cart. In Tarkovsky’s film, as in the first of Pierre Schaeffer’s Five Noise Studies (‘Étude aux chemins de fer’), the rhythmic train sounds serve as a backing track. Indeed, in Stalker the electronic sounds seem to be emanating from the mechanical train-rattle, as though the Zone itself were causing the machine to produce sound in a different way. Once we arrive in the Zone, we see in colour rather than sepia-tinted black-and-white, and perhaps the sounds as well as the sights resonate differently against our senses.

In the title sequence of Red Desert, we feel that we are ‘tuning in’ to new aural wavelengths, that we are able to hear familiar noises in new ways. The ‘nninnnng-nniiinnng’ sound is like a momentary bout of tinnitus, a high-frequency whine that we normally cannot detect but that intrudes on our ears for a few seconds before fading out again. It both responds to and ‘sets off’ the other noises, making us hear that electronic ‘ba-da-dang’ (perhaps by distorting a different ‘original’ noise), and at the same time making us suddenly aware of the lone human voice, or prompting the voice’s owner to start singing. It is important that the voice is not heard until 50 seconds into the credits: we need to have spent those 50 seconds listening to the other sounds before we can hear this one, and the singer needs to have dwelt among those other sounds for 50 seconds before she can join in with her own voice. Red Desert explores how an environment affects an individual and how that individual experiences her environment having been trapped in it for an extended period of time. The title sequence makes us feel that we are learning (or being forced) to see and hear things in different ways. That learning process is reflected in the changes that occur during this sequence.

As the human song begins, the robotic one winds down with a series of dramatic flourishes. We hear another quiet bang, then several rattlesnake-like shimmering noises in the background. Then there are some new sounds: a kind of rapid ‘mao-mao-mao-mao-mao’, which modulates into a ringing, metallic ‘dgl-dgl-dgl-dgl-dgl’ (like a robot clearing its throat) whose final notes repeat like a stuck record before fading away. Is this a repetitive industrial process – a series of percussive blows – or a single blow echoing across space, or a single blow mimicked and repeated by an electronic device? Finally, there is a high-pitched ‘pew-pew-pew-pew-pew-pew, pew-chirrp’ over Vittorio Gelmetti’s credit, resembling a 1950s ‘flying saucer’ effect produced with a ring modulator or Theremin.

Significantly, these electronic sounds stop after this point, just over one minute and 20 seconds into the title sequence. This music has taken us from the already-disorienting sense of listening to human or animal voices that have been distorted, through what sound like mechanical actions made indecipherable, to a kind of apotheosis where sound is not rooted in any recognised physical process. That final ‘pew-pew-pew-pew’ sound is often associated with literally alien, ‘out of this world’ forces because it is so divorced from the sound-producing vibrations we are used to. For those of us who do not understand how it works (or for me, at any rate), it is hard to shake the feeling that the Theremin is an uncanny device that represents a technological step beyond our comprehension. Perhaps Gelmetti’s music only seems to stop here because it goes beyond our perceptual capacities – the rest of that song is for robot ears only.

Forbidden Planet’s innovative soundtrack, by Bebe and Louis Barron, used electronic effects to represent both the advanced technology of Commander Adams’s starship and the hyper-advanced technology (and music) left behind by the now-extinct Krell on Altair IV. Most striking of all are the effects used to evoke an entity born from the accidental marriage of technology and primal impulses: the invisible ‘monster from the id’ that Morbius conjures after hooking his brain up to a Krell machine. In the film’s climax, when the monster is tearing at the walls of Morbius’ compound, it emits noises that sound very much like Gelmetti’s ‘Vwwwwwup, vvwooorp, vwwwwup’ in Red Desert.

In Part 3, I said that those ‘vworps’ suggested something being torn apart, like the Tardis ‘rending time and space.’ In Forbidden Planet, these noises stand for repressed emotions tearing their way out of the unconscious in order to literally tear objects and people apart in the real world. As we turn from the robotic to the human song in Red Desert, we will find this same commingling of modernity and antiquity, of avant-garde melody and primal scream, occupying an ambiguous space that is at once both internal and external.

As the credit before Gelmetti’s tells us, the human song was composed by Antonioni’s long-time collaborator Giovanni Fusco and sung by the composer’s daughter, Cecilia. Fusco’s song, which gradually replaces Gelmetti’s over the course of about 30 seconds, in some ways appears to be in conflict with it. The song comes as a shock after those first 50 seconds, like the shift from pop to avant-garde musique concrète and Stockhausen-esque piano chords in the title sequence of L’eclisse. In the first 50 seconds of Red Desert, we have in a sense become acclimated to the industrial soundscape, and now the intrusion of a human voice seems jarring. This tells us something important about the film’s multiple perspectives: for the most part, we perceive the world as Giuliana does and feel disturbed by futuristic sights and sounds, but we also have the option of feeling like ‘insiders’ whose futurist ears may find Giuliana disturbing.

This last comment assumes that Fusco’s song in some way represents or belongs to Giuliana, and I think this is the most obvious way to understand it. The song is defiantly human (and solely human, without accompanying instruments) in the face of the mechanised noises that dominate the rest of the soundtrack. It is also more obviously melodious than the factory drones and electronic ‘vworps’; this is, more or less, a tune you could hum. However, it is also comparable to Gelmetti’s music in that it sounds very strange and off-kilter. Karen Pinkus argues that it sounds ‘rather electronic, like a Theremin,’2 and at times it almost seems like this voice is trying to fit in with the world around it, trying to sing in harmony with the robots. The voice is reminiscent of the train-whistle in Schaeffer’s ‘Étude aux chemins de fer’, or the coughs and ‘oh’ sounds transformed into music in ‘Étude pathétique’ (the last of the Five Noise Studies). Nardelli observes that

Schaeffer’s aim was not the straight importation of common noises into music: he did not want to make music noise, but to make noise music, using recording technology to transfigure mundane sounds.3

Arguably, the human song in Red Desert inverts this formulation, turning music back into noise without transfiguring it through novel recording technology.

The electronic song is incomprehensible: we cannot confidently assign any meaning, tone, or intention to it. Is the human song any different? Is it legible, on any level? There are no words and only one vowel sound: ‘Ah’. Nor does the melody convey easily discernible emotions. Fusco could have composed something more tuneful, like the sad theme that accompanies Aldo’s broken-hearted odyssey in Il grido. In that case, the under-scoring of the character’s emotional state is clear to the point of being a little obvious and even reductive. It is an apt song for a man who feels obsolete, but as the film goes on we may come to feel that Aldo’s problem is too complex to be encapsulated by this maudlin piano music. Giuliana is like Aldo, both because she feels ‘left behind’ by the world and because her ailment seems rooted in a deeper, harder-to-define existential problem.

Like Aldo, Giuliana does not know how she is meant to love, or to feel, or to interact with reality, and all the ways in which she tries to do these things seem to be wrong, out of place, dysfunctional. The ‘ah’ song is emotionally legible insofar as it conveys this sense of confusion. If there is an ambiguity as to whether the song represents Giuliana herself or a quasi-mechanical performance by Giuliana, or even something external to Giuliana, this is the same ambiguity she experiences as she tries to mediate between her inner state and the demands of her husband, the doctors, and others. Angela Dalle Vacche describes the song as

full of desire, as if it belonged to an ancient soul forever imprisoned in the stone but still striving to reach out […] full of corporeal abandon […] half-human, half-divine.4

She also sees the juxtaposition of robotic and human songs as exemplifying ‘the painful breaking through of new forms out of old molds.’5 When Fusco composed the score for L’avventura, Antonioni asked him to ‘imagine […] how they would have written a jazz piece in the Hellenic era if jazz had existed then.’6 Dalle Vacche’s reading of the Red Desert song suggests a similar combination of the ancient and the new. However, I would read this less in terms of the ‘breaking through of new forms out of old molds,’ and more in terms of old forms striving vainly to adapt to new moulds: a Hellenic instrument trying to imitate jazz, a human voice trying to sing with the machines, a flesh-pink rock trying to be grey concrete – and all failing.

At times, Cecilia Fusco sounds as if she were doing breathing exercises, either to train her voice or to maintain control during a panic attack. At other times, the voice settles into a stable, almost serene melody, then flares out of control, before retreating desperately into the breathing exercise from the start. As such, the song pre-figures Giuliana’s demeanour throughout the film: nervy, impulsive, by turns descending to a depressive mumble and rising to an agonised shriek. The voice wants to make music but does not know how, just as the eyes (of this title sequence) want to see the world but cannot bring it into focus, and the ears want to recognise sounds but cannot connect them with any recognisable source.

Karen Pinkus describes the difficulty, for the viewer, of responding to these origin-less noises:

The ear may take in the sounds as electronic and link them, through an intellectual connection, with the factory but there is still a sense of disjuncture […] [T]he viewer, with varying degrees of consciousness, is left to link ambient sounds with smoke; or to exist in a state of disaggregation and confusion.7

This could serve as a persuasive interpretation of the emotion behind Fusco’s song, which seems always to be reaching for order and connection, to be attempting kinship with the smoke and (as we will see in a minute) the pulsing flames of the factories, but then to be lapsing back into a state of disaggregation and confusion. Roberto Calabretto argues that

[t]he difficulty in identifying the sources of sounds, proof of an uncertain and undefined universe, is akin to the recurrence of out-of-focus shots, with ambiguous colours.8

Antonioni has a penchant for insoluble mysteries about where people end up: Anna in L’avventura, Vittoria and Piero at the end of L’eclisse, the corpse in Blow-Up. But as Calabretto says, not knowing where something came from is in some ways more unsettling. Perhaps this is the real mystery behind the disappearances I just listed. Never mind where they ended up; who (or what) were Anna, Vittoria, Piero, or the corpse, in the first place? The singer at the start of Red Desert does not know what she is seeing or hearing, and this is why she finds herself not only trapped in an ‘uncertain and undefined universe,’ but possessed of an uncertain and undefined self.

Angelo Restivo compares the effect here to the ‘play between interiority and exteriority’ in the title sequence of Zabriskie Point, which he calls ‘in some ways a reprise of the opening sequence of [Red Desert].’9 There, the telephoto-lens shots of the students move in and out of focus, the camera veering nervously from one face to another, while the music (by Pink Floyd) juxtaposes a kind of echoing heartbeat with samples of barely audible dialogue.

Are we among these students or observing them from a distance? Are these sounds coming from inside us, from the students, or from somewhere far away? When the credits end, we see and hear the student debate with documentary-like clarity.

But did the title sequence represent a kind of internalised translation of these images and sounds? As in Red Desert, we begin by occupying a disembodied set of confused eyes and ears, lost in a strange environment that will never feel safe or familiar from now on, even when we do manage to see and hear it more clearly.

The ‘lost’ quality of the human voice in Red Desert’s title sequence is accentuated by its increasing isolation. The electronic music fades away after that farewell ‘chirrp’, and about 30 seconds later the voice suddenly rises to an unprecedented high pitch with a prolonged ‘aaaaaaaaaaaahhhaaaahhh’. This occurs in shot 13, one of the most spatially disorienting images in this sequence.

We see a conglomeration of bars and pipes whose size and distance from the camera are impossible to determine, some of which blur into each other or into the sky. On the right is a rectangular network of blue lines that is almost certainly a ladder but has been made unfamiliar, not only due to the blurring effect and the collapsing of distance by the telephoto lens, but also due to its colour. There is so little blue in this title sequence – most things, including the sky, are grey – and this ladder is like a ghost of sky-blueness. Perhaps the voice has been holding it together until now, but something about this maddening image drives it over the edge. The scream is not only shocking and ear-splitting, it is also gratingly intense. It represents an indecorous loss of composure from which the voice quickly recovers, reverting back to its opening ‘ah-ah-ah’ breathing exercise.

As if in response to this scream, the whining of the factories also dissipates, vanishing entirely within the next 40 seconds and leaving the voice alone on the soundtrack for the final 30 seconds of the title sequence. We can no longer hear the other noises and they presumably can no longer hear the singing voice. Here is that ‘left behind’ feeling that Antonioni evokes so well, infused with a vague sense of humiliation (recalling Aldo in Il grido) after the voice’s emotional outburst. From another point of view, we might see the voice as having more agency here: perhaps it is chasing away the other noises, first the song of the robots and then the factory sounds. That rising shriek may have been a deliberate attempt to surpass the frequency of the oscillating industrial whine and thus drown it out, with the whole song functioning as a kind of meditation exercise to dispel troubling external noise. Again, we find ourselves positioned ambiguously. Do we hear the voice being gradually abandoned by a world that rejects it, or do we hear it transcending a world that it rejects?

As we reach the final shot of the title sequence, the voice comes to the end of its song but never quite finishes. The final three-note phrase sounds like an ending, but an ending whose dominant tone is uncertainty: it is mysterious and ominous, a premonition of as-yet ill-defined bad things still to come. The phrase is sung once, then repeated with the third note unnaturally prolonged. Just as we begin to wonder how long it will continue, it is rudely interrupted (and silenced) by the sound of flames bursting from a flare stack.

The rhythm of this new sound recalls the ‘ah-ah-ah’ breathing exercise at the start of the song, except that these flames are relentless – they will persist throughout the first scene of the film – a cruel parody of the frail, unstable voice they have replaced.

Just before this, the final image of the title sequence is of a ship leaving the harbour, or perhaps arriving in the harbour: I tend to think it’s the former because the ship looks like it is travelling away from a loading crane and away from us, into the upper-left corner of the frame, presumably out to sea.

The image of a boat pulling away from a dock foreshadows Giuliana’s near-escape on a Turkish cargo boat in the film’s penultimate scene. She will consider fleeing the country and will even begin boarding the ship, but will then back away and return to her life among the Ravenna factories. The tension in that scene will echo the tension at the end of the title sequence, where we wonder how long that final note can be sustained (by a non-electronic voice that will soon run out of breath) and where it will end up. This film, like this song, will not give us a sense of closure, but rather of a cry (a ‘grido’) of emotion that is interrupted; a vessel always in the process of escaping but always prevented from doing so; a person in an ongoing state of crisis that can never be resolved.

Next: Part 5, Outside the factory.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Nardelli, Matilde, ‘Some Reflections on Antonioni, Sound and the Silence of La notte’, The Soundtrack 3.1 (2010), pp. 11–23; p. 6

Pinkus, Karen, ‘Antonioni’s Cinematic Poetics of Climate Change’, Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 254-275; p. 266

Nardelli, Matilde, ‘Some Reflections on Antonioni, Sound and the Silence of La notte’, The Soundtrack 3.1 (2010), pp. 11–23; p. 5

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 55

Dalle Vacche, Angela, Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 55

Brunette, Peter, The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 48, quoting TommasoChiaretti, ‘The Adventure of L’Avventura,’ in L’Avventura (New York: Grove Press, 1969), ed. George Amberg and Robert Hughes, p. 208

Pinkus, Karen, ‘Antonioni’s Cinematic Poetics of Climate Change’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 254-275; p. 267

Calabretto, Roberto, ‘The Soundscape in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Cinema’, The New Soundtrack 8.1 (2018), pp. 1-19; p. 16

Restivo, Angelo, ‘Revisiting Zabriskie Point’, in Antonioni: Centenary Essays, ed. Laura Rascaroli and John David Rhodes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 82-97; p. 87