Everything That Happens in Red Desert (11)

Familial terrors

This post contains some discussion of sexual assault, beginning after the row of asterisks.

Worse than the dangers posed to Giuliana by her own body and her immediate environment are the ones posed by her husband and son. We have met Ugo and Valerio separately in earlier scenes, and they have been presented as stark contrasts to Giuliana. They function comfortably in the industrial landscape that she struggles to come to exist within; they seem cool and controlled while she is feverish and spasmodic. When we see Giuliana at home, we see that her loved ones are a key part of what makes that home so oppressive for her, and we understand why she has nightmares while sleeping alongside them. As Philip Novak says:

[T]he characters who […] serve as models of healthy adjustment – the men generally, Ugo and Valerio particularly – come across as monsters. Ugo is insensitive and soulless, as much an automaton as the creepy robot his son plays with; and Valerio is a brat, unconcerned about and unapologetic for the suffering he causes his mother by pretending to be paralyzed.1

I will come back to Valerio’s pseudo-paralysis in Part 33, but for now let’s consider the suffering he causes his mother through his paintings.

The first picture on the left depicts a tree and a building side by side, recalling the transition from trees to factories in the first shot of the film. Valerio’s building seems like an attempt at a house but is disproportionately tall – taller than the tree, more like a block of flats than a single home. The white foliage on the tree’s branches looks like plumes of smoke. From the right side of the painting an ominous red cloud sweeps over the house, covering the greyish sky in the background.

The other pictures are more abstract and harder to make sense of. The background of the second picture suggests the blackness of space. An object in the top-left may be a spaceship or space station, with the yellow blotch representing the rocket exhaust and echoing the colour of the two stars on the right-hand side. Perhaps the spaceship is coming in to land and the yellow rods sticking out of the yellow ground at the bottom of the frame (more visible in the first image below, in which the painting is partially obscured by a chair) are meant to be docking stations in a moon-base.

As for the last two pictures – a red blotch on a black background and a mess of blue and yellow streaks – who knows what Valerio was going for here.

Whether they are figurative or abstract, these paintings demonstrate the little boy’s modern sensibilities. His picture of ‘home’ shows a tree towered over by a building and smoking like a factory, as a cloud of pollutant gas rolls towards it over the house (whose inhabitants, we might assume, are safely stowed inside). Valerio fantasises about inexplicable space adventures, with strangely shaped vehicles travelling among the stars, powered by solar energy and docking on the moon. And when he paints indecipherable nonsense, and his parents dutifully hang it on their bedroom wall, it fits right in with the equally indecipherable Gianni Dova painting, the Sagra della Primavera (Rite of Spring), which they hang on another wall just a few feet away.

Dova was an adherent of the Nuclear and Spatialist artistic movements. Enrico Baj, the founder of Nuclear Art, often portrayed deformed human figures with arms outstretched, as in Two Children in the Nuclear Night.2 Dova was surely thinking of such images when he painted the splayed limbs in his Rite of Spring.

Nuclear artists, as Lara Demori says, sought new effects through ‘the organic matter that spills randomly onto the canvases,’ and through what they called ‘“primary images”, a label that echoes Jungian studies on the notions of archetype and collective unconscious.’3 In an age when some of the most progressive artists are embracing their most primal, unconscious, child-like instincts, the automatism of an actual child’s painting takes on a new profundity. Indeed, Valerio’s black-and-yellow star painting recalls both the mural in Ugo’s factory and Baj’s Nuclear Forms, which consists of smears of black paint (with hints of red) on a yellow background.4

Like the factory mural, Valerio’s painting may represent both an aspirational ‘journey to the stars’ and a celebration of the explosive industrial processes taking place here on earth, which he has learnt about from his father. These pictures loom over Giuliana in her sleep, reminding her how well her son fits into the world that has left her behind.

Enrico Baj, like Antonioni, had a complex attitude towards the nuclear age and technological progress. The humanoid figures in his paintings are sometimes referred to as other-worldly ultracorpi (‘ultra-bodies’), which is also the word used for ‘body-snatchers’ in the Italian title of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. These creatures represent both ‘the success of science and the empowerment of man’ and the ‘inherent danger of altering the natural order.’5 Lucio Fontana, founder of the Spatialist movement, articulated a more purely utopian futurist vision in his Manifesto Blanco:

The old static images no longer satisfy the modern man who has been shaped by the need for action, and a mechanized lifestyle of constant movement. […] Calling on this change in man’s nature, the moral and psychological changes of all human relations and activities, we leave behind all known art-forms, and commence the development of an art based on the union of time and space. The new art takes its elements from nature. […] Colour in matter, developing in space, assuming different forms. Sound produced by artefacts as yet unknown. […] The subconscious, that magnificent well of images perceived by the mind, takes on the essence and form of those images and harbours the notions that make up man’s nature.6

This is the same kind of blissed-out rhetoric we heard from Luigi Russolo in Part 3, and some of Fontana’s comments anticipate Antonioni’s Cannes statement about L’avventura (to be discussed in Part 19). Fontana was inspired by Red Desert to make his painting Concetto spaziale, Attese, on the back of which he wrote, ‘I returned from Venice yesterday, I saw Antonioni’s film!!!’7 The front of the canvas is covered in solid, bright red, with a series of vertical cuts Fontana made with a Stanley knife. Fulfilling the artist’s ‘spatialist’ goal, ‘to explore and create space beyond the canvas,’ the slashes create what Olivia Tait calls ‘a mesmerizing illusion of infinite depth and space.’8

Dova’s Rite of Spring does not attempt such dramatic three-dimensional effects. Arguably, it does the opposite: it collapses space in a way that chimes with the telephoto-lens shots in Red Desert. This painting fits comfortably into a film where such ‘flattened’ images are the norm. In his manifesto, Fontana commented that in the idealised portrayals of representational art (which we should now relegate to the past),

The observer imagined that one object was, in fact, behind another; he imagined in the portrayal the actual difference between the muscles and the clothing.9

For example, the human figures in Botticelli’s Primavera are artfully placed amid a secluded forest grove, with their feet resting on the grass in the foreground or middle-ground, fruit trees extending into the background, and patches of blue sky in the far background.10 As we stand in front of it, the painting transports us, bodily, into this illusory three-dimensional space.

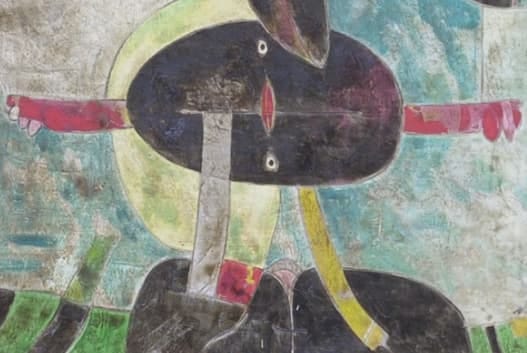

Dova subverts this in several ways in the Rite of Spring.11 In his seasonal idyll, the ultracorpi seem to exist in a world made two-dimensional. Standing before this painting, we feel ourselves and our surroundings flattened as well.

Is the green at the bottom of the frame supposed to suggest grass, and are the black shapes supposed to be plants or trees emerging from the ground? They are less like Botticelli’s shadowy black tree-trunks than they are like the mysterious structures Valerio paints emerging from the yellow ground of his alien planet.

In the Rite of Spring, what is represented by the patchwork background behind these figures, and is that a yellow sky behind the patchwork? Or has the sky itself, the forest, and the whole environment been turned into one flat, fragmented canvas? Look at this section of the painting:

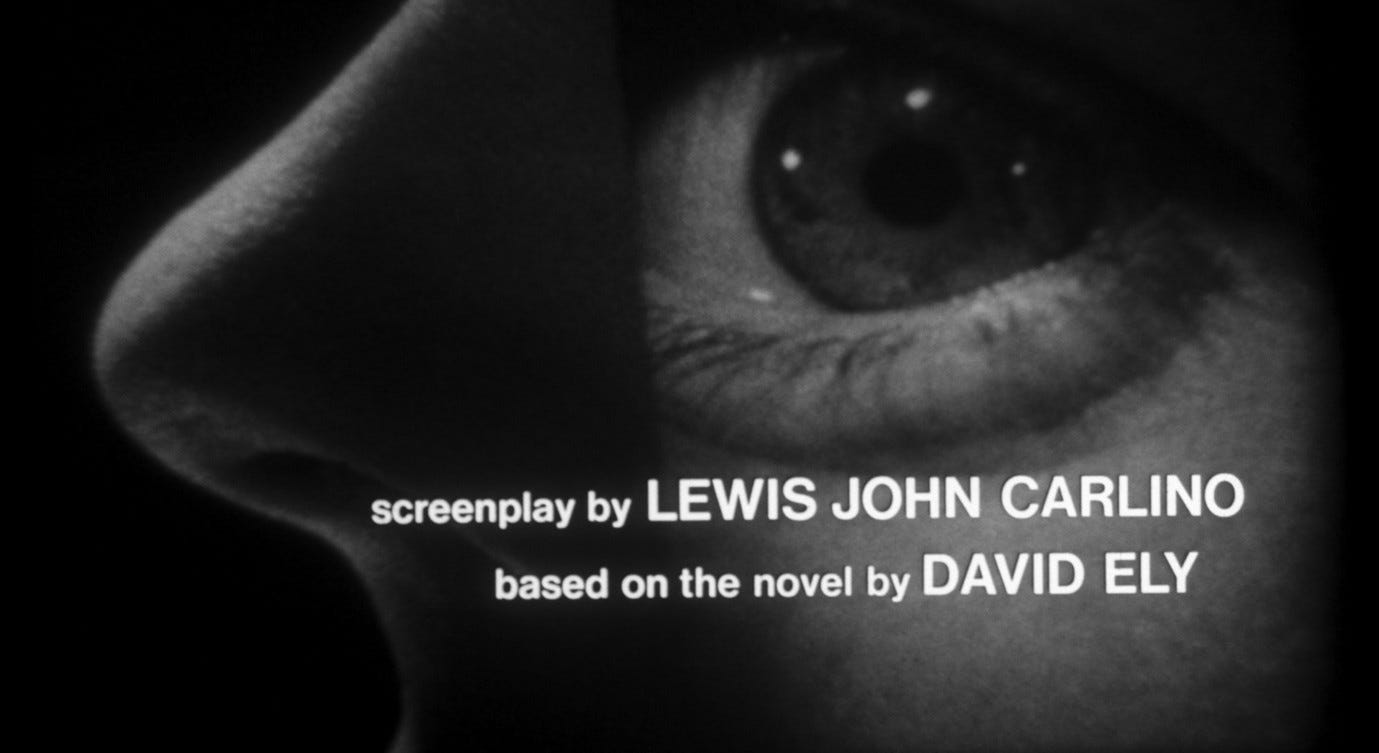

Are those clenched teeth attached to the horizontal leg-like object, or are they in front of it, or are they behind it? Are they embedded in the patchwork surface, as the two eyes seem to be? The placement of what look like eyes near what looks like a mouth prompts us to see a kind of face here. Is the yellow patch with the eyes in it a head, and is this attached to the entity on the left? Is it smiling or scowling? As in the title sequence of Seconds, the features are human-esque but distorted and mis-placed.

If Dova was thinking of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, perhaps the central figure in his painting is supposed to recall the girl selected to be sacrificed, who dances herself to death at the end of the ballet.

Here is another face with differently-placed features: eyes now level with the mouth, and the mouth represented as a pair of red lips rather than lipless clenched teeth. This mouth is intersected by a slit (like the slashes in Fontana’s painting), from which a grey leg extends on the left. Another (yellow) leg extends from the edge of the black torso, in what could almost be a three-dimensional effect (that is, this leg could be attached to the other side of the body). Both legs are embedded in huge black mounds at the base of the canvas – are these feet? Or shoes, like those of the other girl who famously dances herself to death (in The Red Shoes)? One shoe has a segment of lurid, fleshy red with dark vein-like structures in it and a small yellow streak. The figure’s mutated arms have the same painful, wounded red colour. This central figure in the Rite of Spring seems beset by larger and even more mutated figures on the left and right; it seems kicked and hammered by them into an agonising balletic pose, while also being weighed down from below by those clumping black boots. The outstretched arms suggest the terror and protest of Baj’s child casualties facing an atomic blast, but also the bowing gesture of a dancer completing her performance.

From one point of view, Dova’s painting might recall Harlan Ellison’s story, ‘I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream’, with its horrific technologically-induced transformations of the human form. Perhaps this is what it means to Giuliana. For Ugo, though, this painting might suggest a more positive vision of our species’ evolution, one that embraces the ultracorpi and the natural energies unleashed by their dance. Who needs Botticelli’s vision of nature as a protective, encircling glade in which Love and the Graces perform their elegant dances? For Gianni Dova, spring rites are celebrated in a space that looks entirely man-made, defiantly and economically flat, torn apart then patched together again, smudged by pollutants in the process, and populated by exciting new bodies with new faces, new expressions, and new emotions. This, Ugo and Valerio might feel as they look at the painting, is the exciting adventure we have embarked upon.

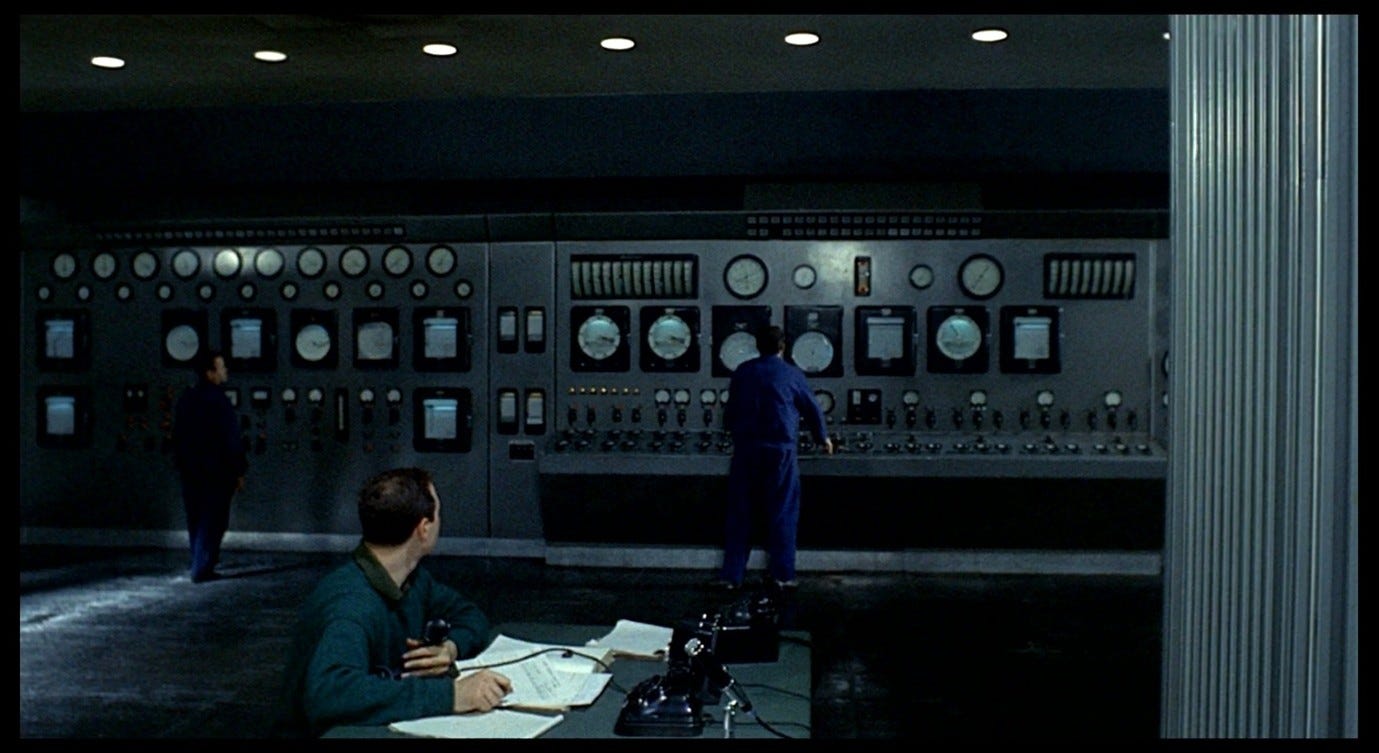

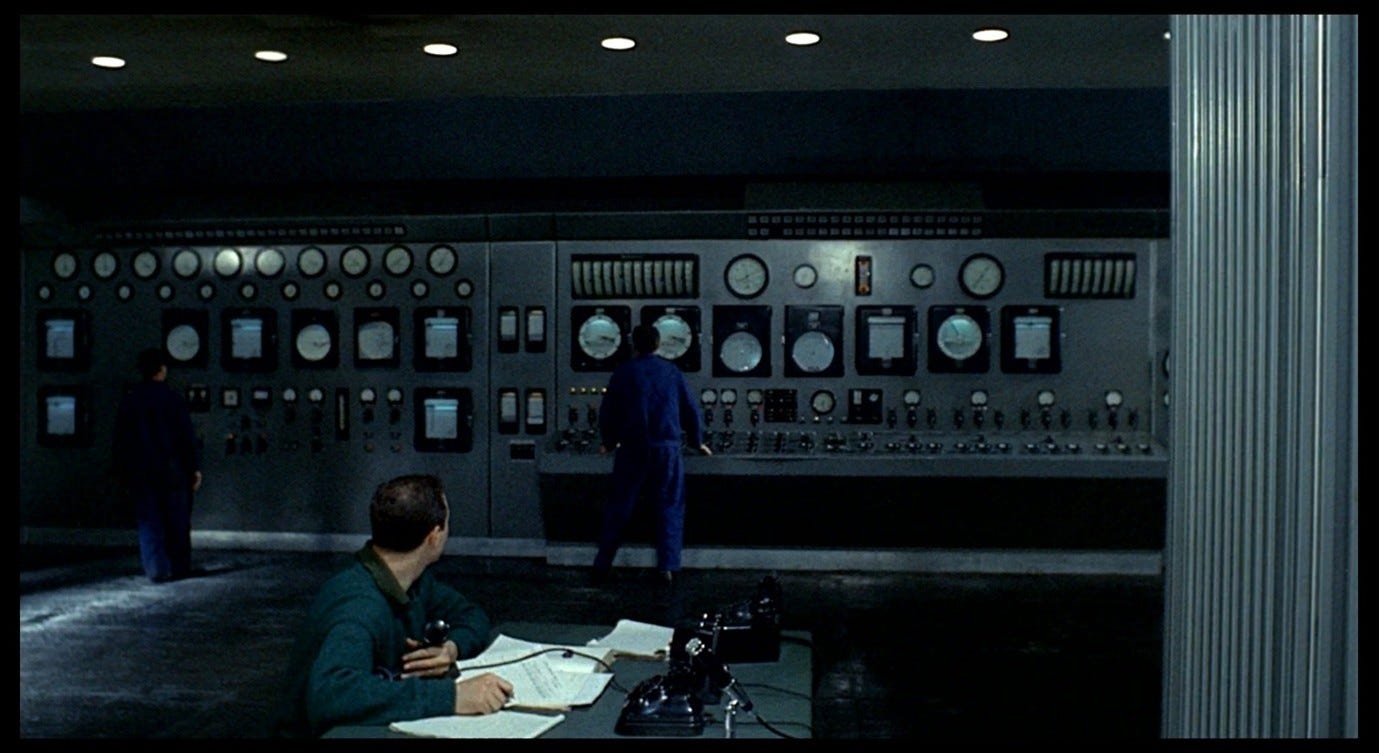

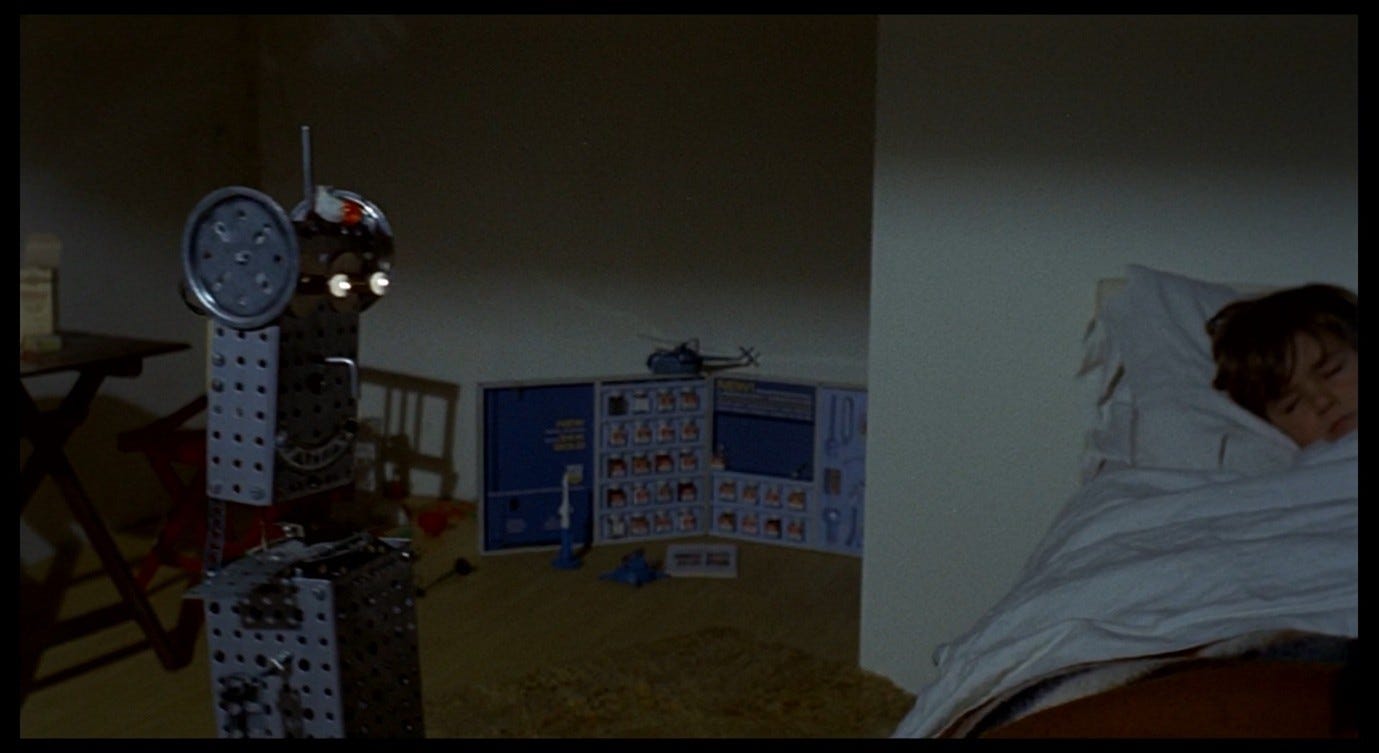

The robot in Valerio’s room embodies a different form of automatism from the paintings (including Valerio’s) discussed above. Its back-and-forth movements remind us of the child’s mechanical side-stepping along the rail outside the factory, as well as the similar side-stepping movements of Ugo’s employees in the control room.

The fact that Valerio has set this robot to patrol his room all night tells us something about his attitude to technology: the robot, with its permanent metal smile, is there to protect him. Its repetitive mechanical noise acts as a lullaby, an oscillating reassurance of safety and protection. Perhaps most importantly, Valerio has built this robot himself. In the background, we see that he is also working on miniature helicopters.

The middle-class child of the early 60s can be expected to master abstract expressionism, robotic engineering, and state-of-the-art aviation before the age of ten, and thereafter to grow up with a mindset that is comfortable with novelty.

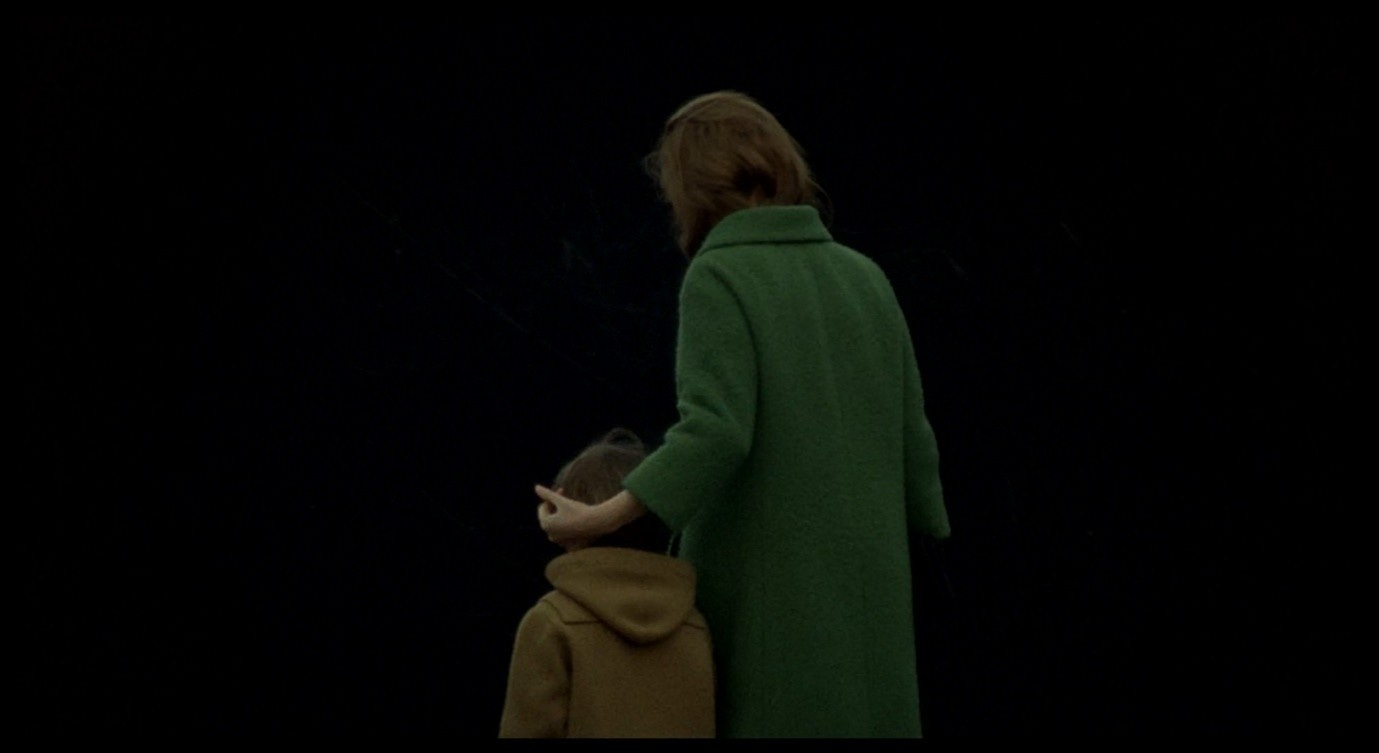

Giuliana strokes Valerio’s hair uncertainly, much as she did at the end of their lunchtime walk in the earlier scene.

As she approaches the bed, her fingers clutch the air as though to rehearse the stroking gesture they are about to make, or as though Giuliana were debating whether to stroke her son’s hair or not.

Her fingers continue to move as she steps away from the bed.

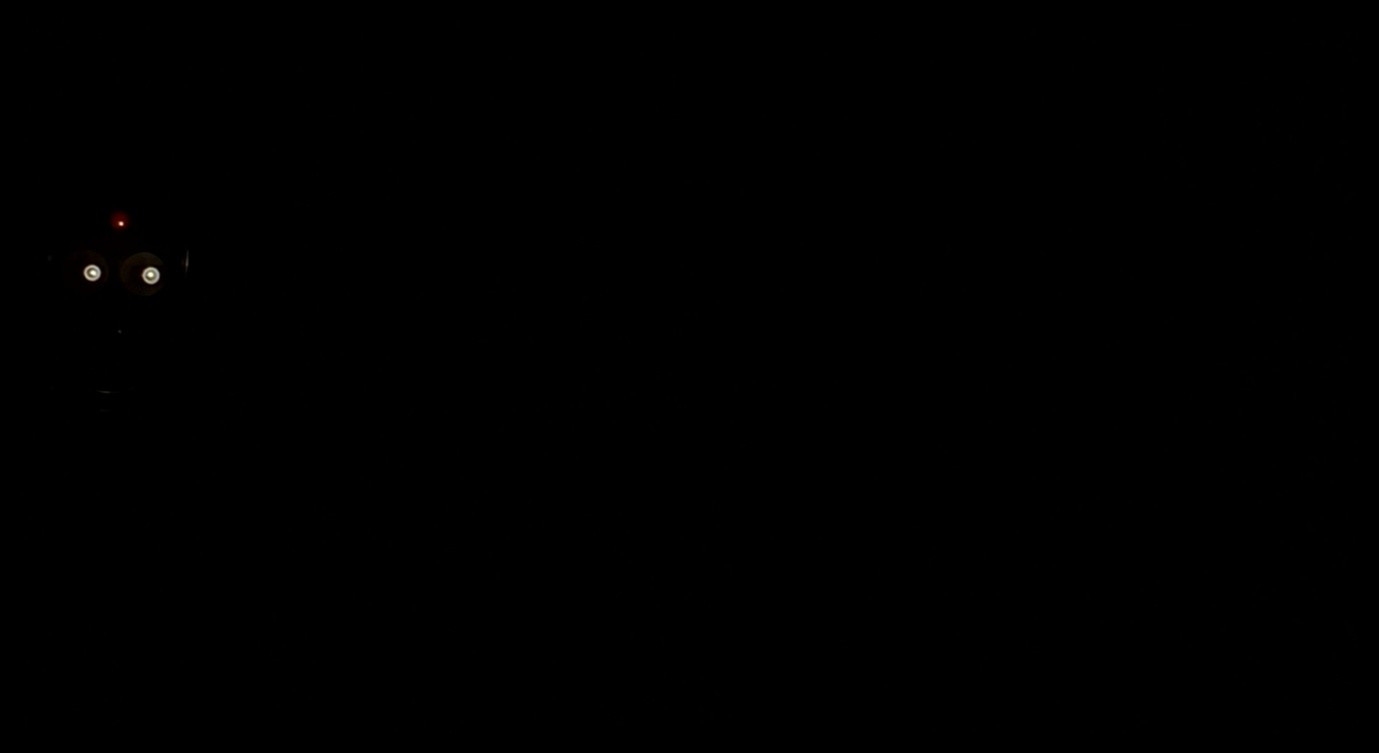

She is nervous about touching Valerio’s hair, not because she might wake him up – he is very firmly in sleep mode – but because this caress might not bring her the sense of connection she is looking for. And it clearly does not: she might as well be caressing thin air. Whatever it is about Valerio that frightens Giuliana, it persists at the end of this encounter. She may have stopped the robot from patrolling but its eyes continue to glow ominously in the dark, just enough to illuminate its implacable smile.

This anticipates Giuliana’s later, devastating revelation: that she is surplus to requirements in her own home because her son has no need of her love or protection.

In The Sleepwalkers, Hanna Wendling experiences a similar form of night-time alienation from her home and her son:

Even with regard to the boy she was not immune from this mysterious feeling of estrangement. When she woke up in the night she found it difficult to realize that he was sleeping in the next room, and that he was her son. And when she struck a few chords on the piano, it was no longer her hands that did it, but unfeeling fingers which had become strange to her, and she knew that she was losing even her music. Hanna Wendling went to the bathroom to wash away her morning in the town. Then she contemplated herself carefully in the mirror, looking to see whether the face there was still hers.12

Perhaps Giuliana goes into Valerio’s room to check on him, not because she is afraid he may be in danger but because, like Hanna, she is unsure whether he is really there, or whether he is really her son. Hanna’s loss of control over her hands is another symptom she shares with Giuliana, as is her sense of dissociation from the self she finds in the mirror: this is a topic I will return to in Part 17, with reference to Giuliana’s displacement of her illness onto an ‘other woman’ who was in the clinic with her. As with Hanna’s discomfort amid the ‘arbitrariness’ of her previously ordered home (discussed in Part 10), there is a sense that Giuliana is breaking the rules of her world, or that those rules are breaking around her. She wakes when she should sleep, her home is not a home, her son is not her son. In Red Desert, the rule that a parent should protect their child comes to seem arbitrary, nonsensical, when Valerio is so secure amongst his robots and his mother experiences every aspect of her environment as a mortal threat.

* * * * *

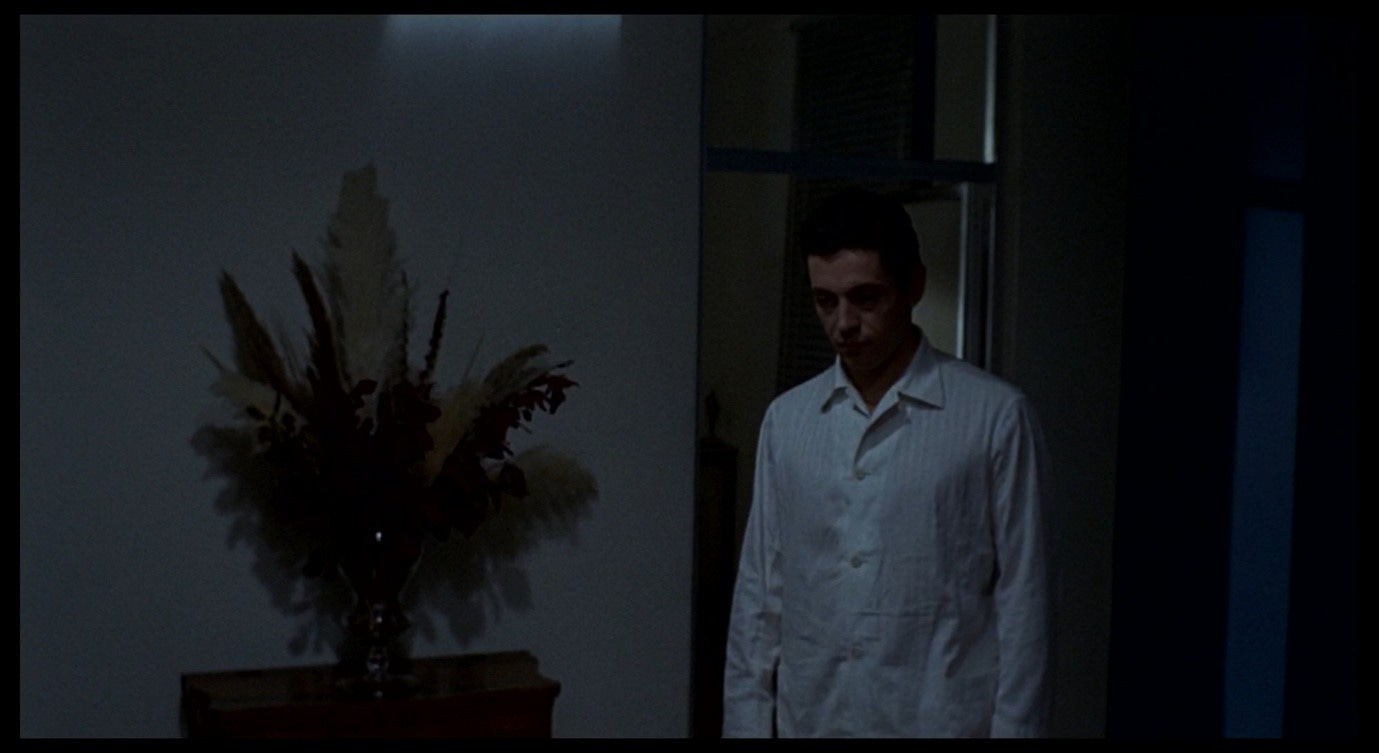

Ugo, who was sleeping soundly at the start of this sequence, has evidently woken up, and appears in the bedroom doorway looking immaculate, without any sign of fatigue.

He does not rub his eyes or stretch his limbs, but has simply switched into awake-mode, as he will do later when awakening from his nap in Max’s shack. Being a picture of functionality and wellness himself, Ugo deals with his wife’s illness by minimising or dismissing it. Looking at the thermometer he just says ‘qualche linea’ (an abbreviation of the phrase ‘qualche linea di febbre,’ meaning ‘a low-grade fever’), and when she protests that her temperature is alarmingly high, he retorts with a shrug, ‘it’s normal.’

When she tells him about the quicksand in her dream, he interrupts her, saying, ‘but no [ma no],’ ostensibly to dispel the nightmare but also to dismiss her fears as unreal, imaginary. If only she could get it into her head that she is not sinking, that she is on stable ground, she would be cured.

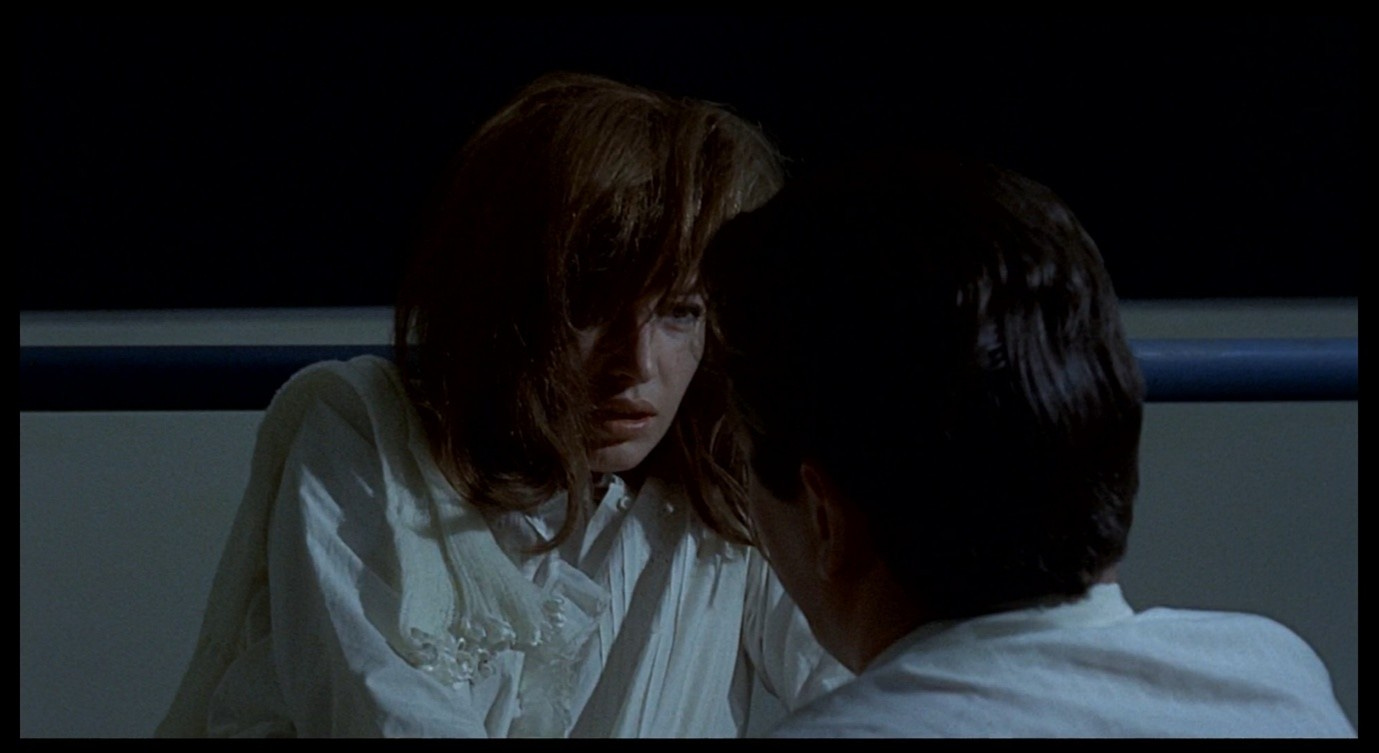

Monica Vitti’s voice, in this scene, is broken and hesitant. After describing her nightmare, she cries out in terror and buries her face in Ugo’s shoulder.

Here is how the screenplay describes what follows:

Then [Ugo] begins to kiss her neck affectionately. Giuliana seems not to notice, but because Ugo insists, in a manner that is less and less affectionate and more explicitly erotic, she gets up and detaches herself from her husband. But Ugo does not accept defeat [non si dà per vinto or ‘does not give himself as vanquished’], going to her and continuing to kiss her. Giuliana tries again to fight back [cerca ancora di reagire], convulsing as though with a sensation of pain, but the pleasure of the embrace, and of the kiss that follows, gets the upper hand.13

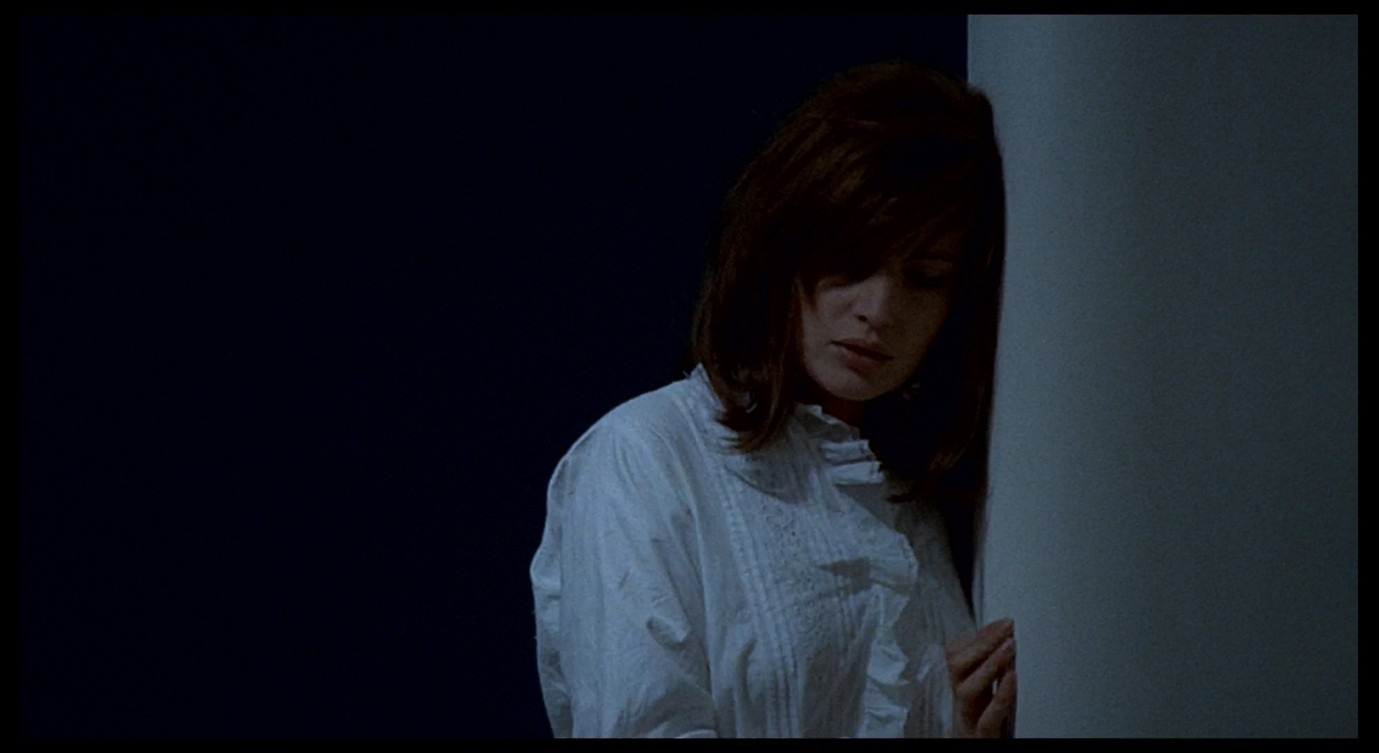

Much of this is captured in the finished film, but with some important differences. After burying her face in his shoulder, Giuliana suddenly recoils from Ugo, and it is not immediately clear what she is responding to. The reverse-shot of Ugo shows him looking fixedly at her with a kind of matter-of-fact desire, but now Giuliana is writhing desperately against the metal railing.

The electronic score returns, but instead of the agitated, pulsing noises we heard before, we hear a series of discrete sound effects, each of which resounds, echoes, and fades as though we were hearing them from a distance, through a cavernous space like a cave or a warehouse. The languid, resonant, mysterious tone of this music could evoke amorous sighs (the choir of robots trying to set an erotic mood) but could also be read as sinister and haunting (like a choir of erotic robots).

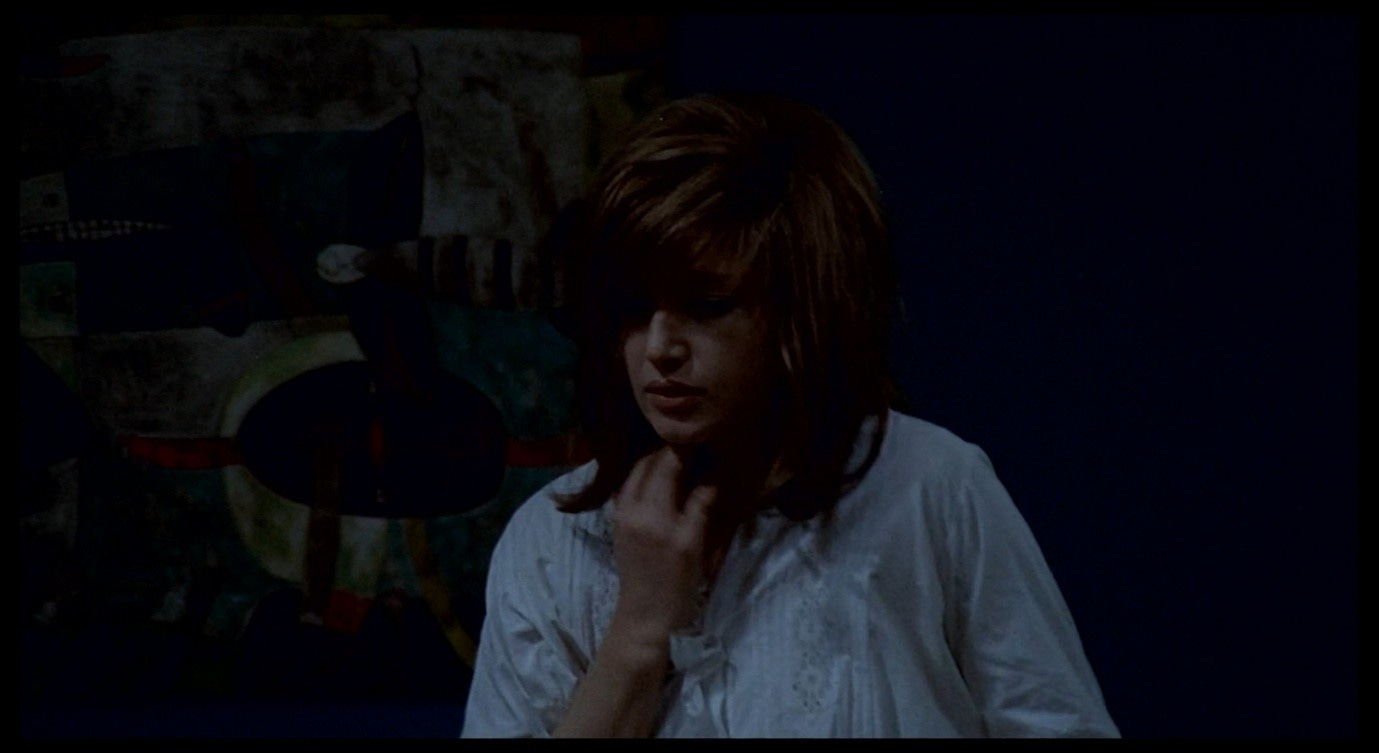

After kissing Ugo once, Giuliana gets up and moves away, the camera shakily following her as she readjusts her shawl, blinks down at Ugo as though she were afraid of him, and presses herself against the curved white wall. The Rite of Spring is conspicuous on the wall behind her.

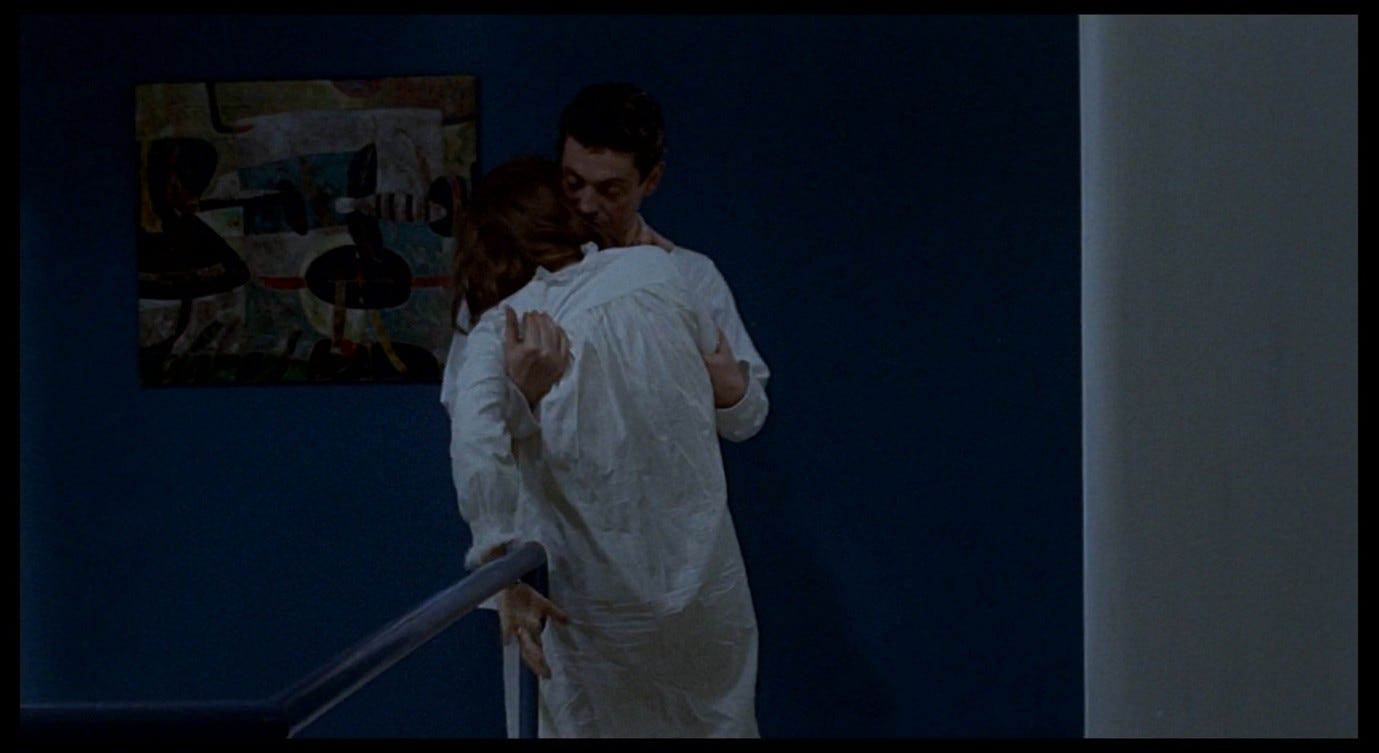

For a moment, she is caught in a very typical Antonioni composition, with the solid blue background dominating the left two thirds of the screen and the white wall dominating the right third. She presses her head and body against the whiteness as though wanting to disappear into it, but the composition emphasises her sense of entrapment, all the more so as the camera cuts to a wider shot and we see Ugo closing in from the left, following the direction of those attacking horizontal limbs in the painting.

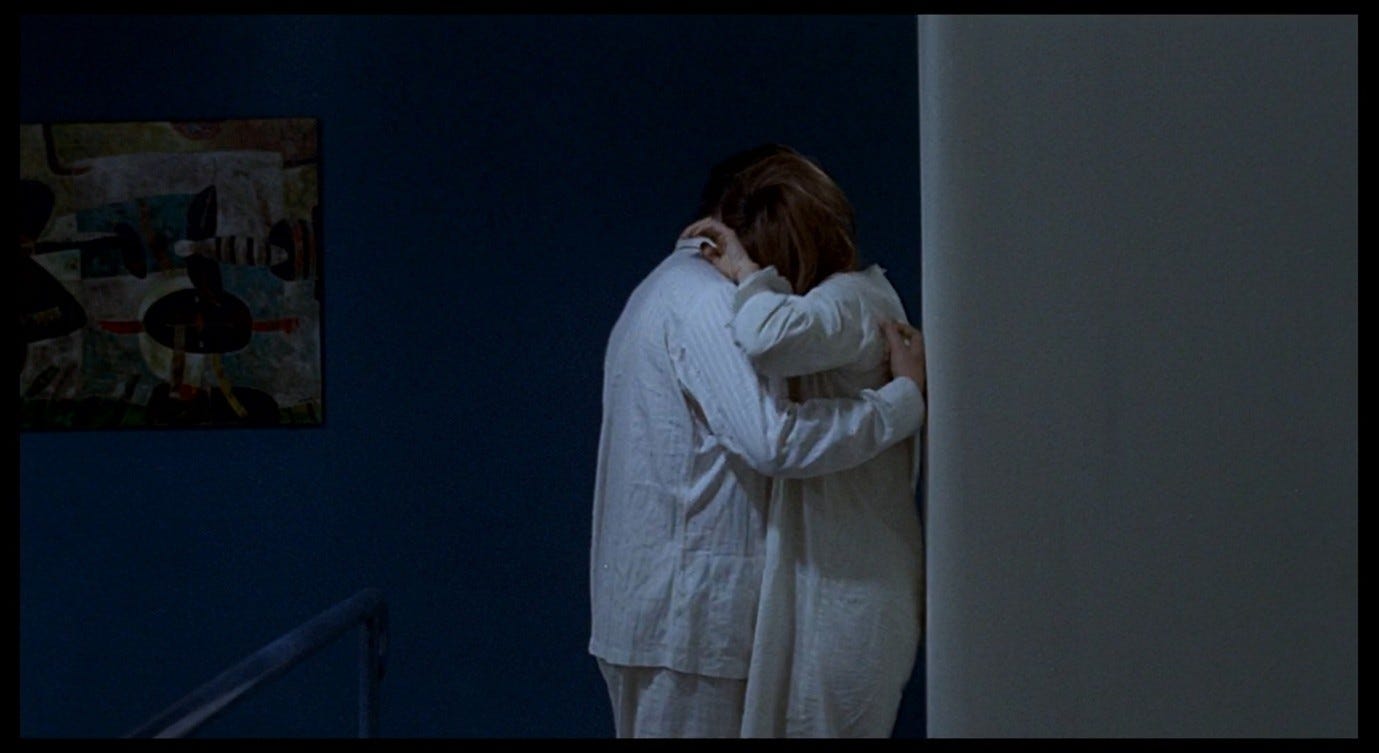

Giuliana is now clutching herself in an expression of physical pain, but Ugo – wordlessly, and without any visible emotion – takes hold of her. As he makes contact, she seems to notice him suddenly (snapping out of her trance), and she instinctively puts her hands up in a gesture that seems intended to push him away.

When her hands find themselves resting on Ugo’s shoulders, they flop down and we see her left hand form a loose fist, gently pressing against Ugo’s arm and then his shoulder.

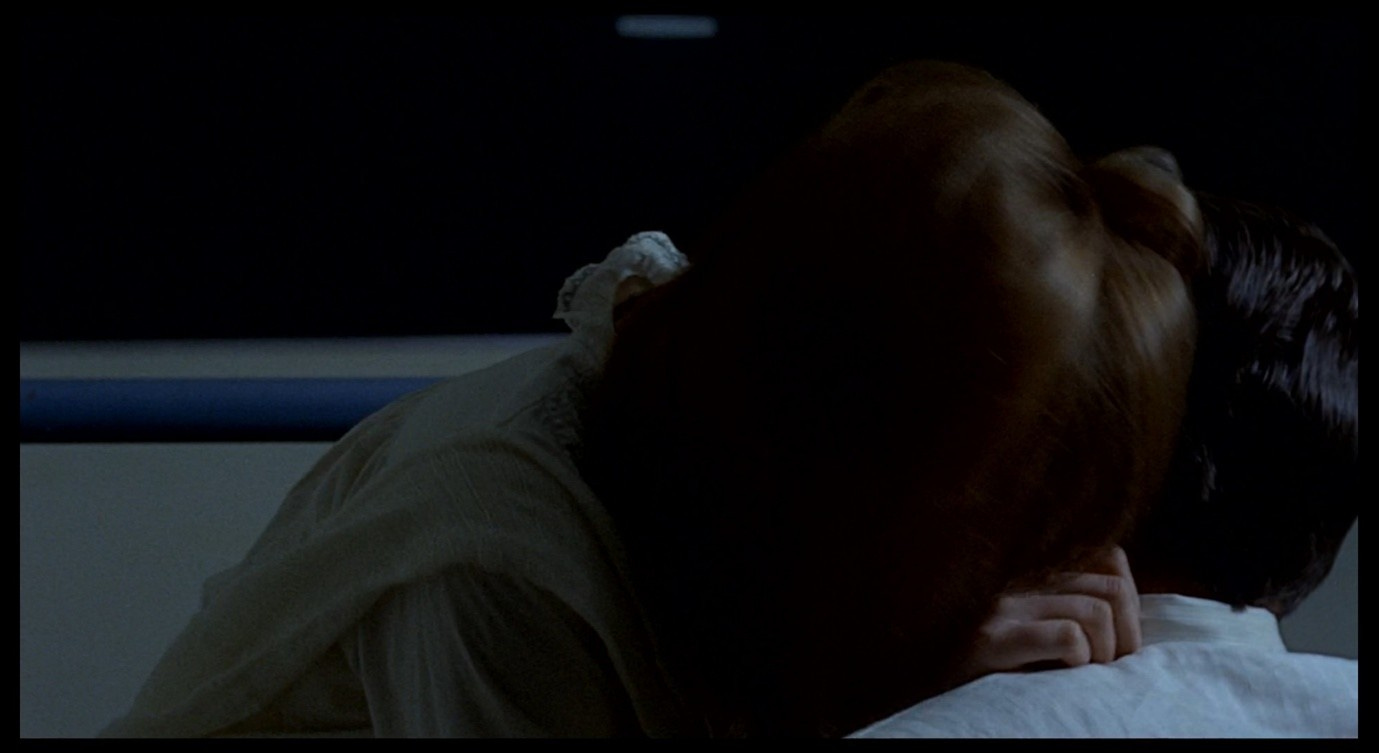

As Ugo moves her across the landing, her left hand reaches down to grab the banister, then (as we cut to a medium close-up) rises to clutch at Ugo’s shirt, then writhes behind his head.

None of these hand gestures seems indicative of consent. For example, the clutching of Ugo’s shirt might not be meant to draw him to her so much as urge him to hear what she is telling him. In fact, as her hand writhes behind his head, she explicitly says ‘no.’ Her speech then disintegrates. The murmurs and grunts that follow might be a deconstructed repetition of ‘no’: we hear the ‘n’ sound, then an ‘oh.’

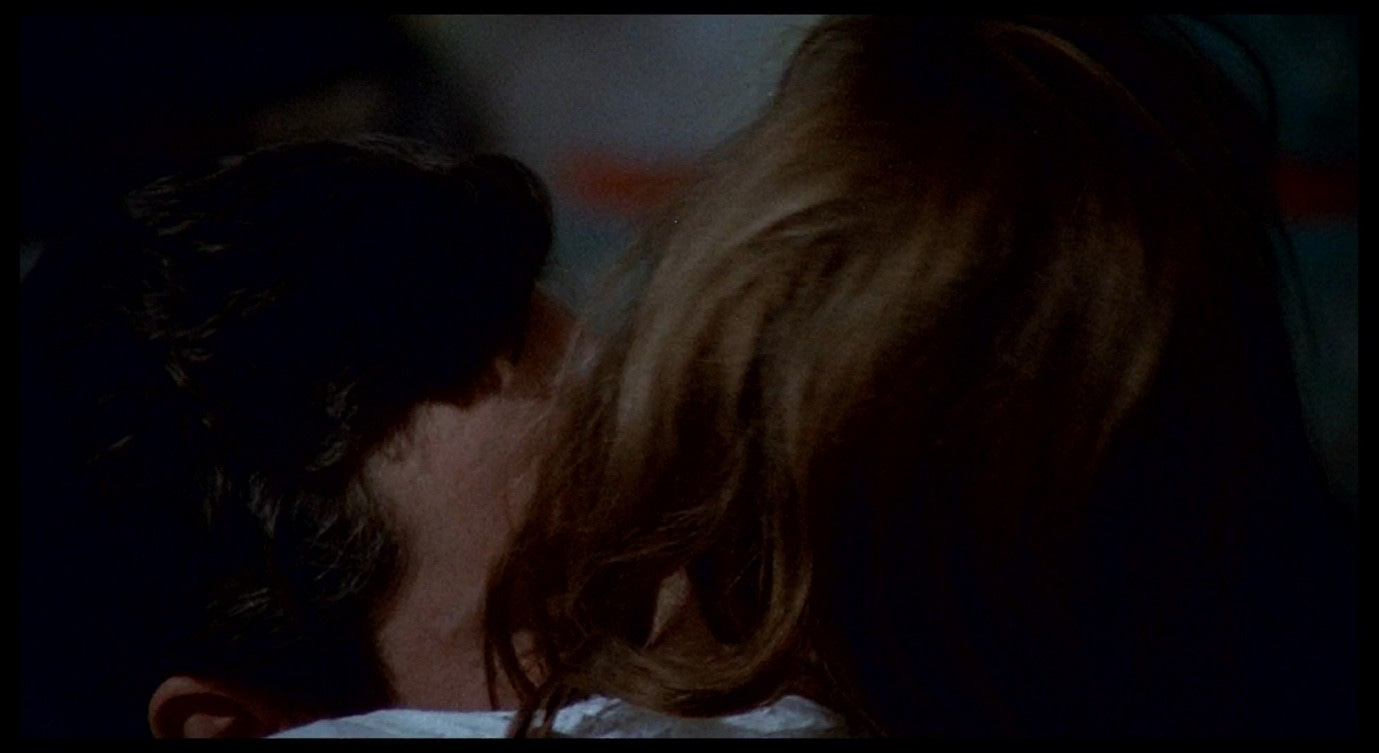

The screenplay indicates that she is overcome by pleasure and implies that the love-making will continue after the scene ends. But the conclusion of this scene, as filmed, seems to suggest something else. The camera focuses on the back of Giuliana’s head in extreme close-up, with Ugo’s face buried in her neck as he continues to kiss her. After a few seconds, Ugo becomes still. The two are locked in a static embrace. He seems to have given up, and his stillness might be read as despairing or passive-aggressive, but also as characteristically robotic. As with Valerio’s sentry, Giuliana seems to have found her husband’s off-switch. The camera tilts up until the top half of the frame is filled with the Rite of Spring, now rendered even more abstract by being out of focus.

This is one of several scenes in Antonioni’s films where a woman resists a man’s advances and he imposes himself on her – or, to be frank, sexually assaults her. Towards the end of L’avventura, Sandro tries to make love to Claudia following a moment of crisis. He has been vividly confronted with his professional failure and, in a state of frustration, he forces Claudia onto the bed, ‘as though he wanted to take his bad mood [malumore] out on [her],’ as the screenplay puts it.14 She, fighting him off, complains that he is behaving like a different person, prompting him to invoke the film’s title: ‘And aren’t you happy? You’ve got a new adventure [Hai un’avventura nuova].’

Sandro plays on the double meaning of ‘avventura’ as both ‘adventure’ and ‘affair’, and Claudia is horrified by this attempted joke. The exchange recalls the similar argument between Anna and Sandro earlier in the film, when she complained that she did not ‘feel’ him anymore, and he responded, ‘Even yesterday, you didn’t feel me?’, referring to their love-making in his apartment. ‘You always have to dirty [sporcare] everything,’ Anna replied – her last line in the film.

Ian Cameron argues that

Claudia’s problem is very different from Anna’s: she is worried about whether Sandro loves her, not about her feeling for him, of which she is certain.15

But I think part of the problem is that Claudia is learning not to be certain of any of her (or other people’s) feelings. Sandro says of Anna,

She behaved as though our love – mine, yours, her father’s in a certain sense – weren’t enough for her, or were of no use to her.

Later, Claudia will be equally disturbed to find her feelings for Anna dissipating – after a few days, she is afraid Anna will turn out to be alive. Towards the end of L’eclisse, Vittoria will say to Piero, ‘I wish I didn’t love you, or that I loved you much more.’ To say that Claudia’s problem is ‘very different’ from Anna’s is to make a distinction that these films refuse to make. Like Anna, Claudia finds herself not wanting to make love with Sandro, disgusted (in fact) by the prospect of making love with him, to the point that his ‘love-making’ becomes a violation. Anna’s comment, ‘I don’t feel you anymore,’ is a plea for emotional connection; Sandro’s lewd remark is a callous rejection of that plea.

At the end of La notte, Giovanni refuses to accept Lidia’s conclusion that they have fallen out of love with each other, and attempts to shut her up by ‘making love’ to her. The screenplay says that after resisting for a while,

Lidia closes her eyes and allows herself to be embraced. A kind of carnal lust devours her, in remembrance of that which was and which will never be again.16

As in Red Desert, the film deviates from the screenplay in that there is no indication of acquiescence on the woman’s part, and Giovanni’s ‘seduction’ comes across as an assault.

The carnal lust, driven by a memory of something that no longer exists, seems entirely on his side, and (like Sandro’s angry, frustrated assault in L’avventura) entirely joyless. Sam Rohdie makes this connection too, saying that Lidia is

assaulted, grabbed, pounced upon by Giovanni, so desperate as no longer to feel her. The violence of Giovanni’s act recalls the violence of Sandro’s remark to Anna, in L’avventura, before she disappears on Lisca Bianca, ‘And didn’t you feel me the night before?’17

William Arrowsmith describes Giovanni as

a black figure on [Lidia], around her, his blackness overwhelming her, drowning her, trying to make her drown with him, pushing her down into the emptiness, the desert.18

But then he says:

Each viewer must decide for himself whether Giovanni succeeds in overwhelming Lidia, but to me there seems no doubt that he fails. Why? Because the scene has been so carefully prepared for in the party, in her ripening loneliness, in the sequence of her dancing alone, and in her rejection of Roberto’s invitation to love […] The world changes, feelings change.19

This is not the last instance we will see of a critic blurring the issue of sexual assault: Seymour Chatman says both that Giovanni ‘forces himself’ on Lidia and that he ‘forcefully makes love to her.’20 This kind of hedging is far more common than the directness of Eugenia Paulicelli, who describes Giovanni as ‘intent on raping Lidia.’21 Antonioni himself showed an ambivalent attitude towards Giovanni’s actions:

The man becomes hypocritical, he refuses to go on with the conversation because he knows quite well that if he openly expresses his feelings at that moment, everything would be finished. But even this attitude indicates a desire on his part to maintain the relationship, so then the more optimistic side of the situation is brought out.22

The topic of men abusing women – and specifically the topic of sexual assault – is an important one in Antonioni’s work, and one that I will discuss in more depth in Part 40, with reference to the scene in Corrado’s hotel room. But it is important to stress, at this early stage, that I will not be making the case for Antonioni as a feminist whose primary intent is to critique patriarchal abuse. Indeed, there is evidence that, in the course of making some of his films, Antonioni was something of an abusive misogynist himself.23 That may be enough to make you stop watching his films (and stop reading this blog).

For the most part, however, Antonioni’s films seem (to me) more focused on an empathic engagement with the female characters’ perspectives, including their critical perspectives on the men’s behaviour. I detect none of the ‘optimism’ Antonioni refers to in the ending of La notte. Later in the same interview, he offers a less hopeful reading of this scene:

The woman is still willing to discuss, to analyze, to examine the reasons for the failure of their marriage. But she is prevented from doing so by her husband’s refusal to admit its failure, his denial, his inability to remember or unwillingness to remember […] Instead, he tries to take refuge in an irrational and desperate attempt to make physical contact.24

What all these scenes have in common is the dynamic between the woman’s and the man’s point of view. In each case, she is trying to acknowledge something important about the dysfunction in their relationship: something has changed, something has broken, and this needs to be addressed before they make love, or get married, or stay married. In each case, the man responds by reducing the relationship to sex, specifically to sex ‘in the moment’. Sandro’s riposte to Claudia (‘you have a new adventure’) is telling: it is based on the assumption that both she and he are driven by a desire to make love now, in the present, and if that means making love to a new and different person, so much the better. The newness of the affair (un’avventura nuova) underlines its positioning in the present, as opposed to the past. It does not matter how broken the relationship has been until now, it does not matter who has gone missing or died, and it does not matter if our lives or careers have failed. All that matters is this love-making and this orgasm.

The scene between Ugo and Giuliana in Red Desert replays this dynamic in a new context. The film is not interested in anatomising the problems in their relationship. When Giuliana tries to express herself, she is not directly saying that there is something wrong with their marriage. The nightmare of the bed descending into quicksand conveys the existential terrors that beset Giuliana internally and externally. Instead of saying to one individual, ‘I don’t feel you’ or ‘I don’t love you’ or ‘You’re like a different person,’ Giuliana is saying that her grasp on the whole world is failing. When Ugo responds by embracing her, unlike with Sandro or Giovanni we have no sense of the personal failures or frustrations he might be acting upon; perhaps he has none. Nor does it seem like his desire is excited by Giuliana’s distress, as such. Perhaps he thinks that love-making would cure her, or perhaps he is aroused by physical contact with her and automatically tries to have sex. It is the ‘automatic’ part that makes this scene uniquely disturbing. Unlike the men in the earlier films, Ugo does not even seem to have heard what his wife is telling him. He is like a Stepford Husband (if the husbands were the robots), coldly initiating the sex protocol and then shutting it down when he meets a certain level of resistance.

This is similar to the in-the-moment sensuality of the other male characters referred to above, but taken to a logical extreme. In the context of Red Desert, this sensuality is also figured more clearly as something ‘modern’, akin to the other features of Giuliana’s environment that she struggles to come to terms with. Her sterile, functional home; her self-sufficient child; her robotically affectionate husband; all of this induces her fever, her nightmares, her flailing contortions, and makes her feel as though she were drowning in quicksand. It is hard to crystallise why these things affect her in this way, but focusing on the parallels between Sandro, Giovanni, and Ugo helps to illuminate one aspect of the problem. In the red desert, no one cares about the lost oases or the people destroyed along the way. They focus only on the present and the future, the next embrace, the next conquest.

One simple way to look at Giuliana’s convulsions, her repeated backing into walls, and her fear of venturing downstairs into the darkness, is to say that she is fleeing from ‘the thing that approaches’, whatever that is. Something is changing, something is ‘next’, and she clings to the walls and floors to guard against this ‘next’ thing. For Ugo to behave as though they could make love at a moment like this, as though her fears could simply be neutralised by an orgasm, is ironically a fulfilment of her greatest fear: that her self and her sense of reality can be exchanged for another self, another reality, within a moment.

Arrowsmith’s reading of La notte (quoted above) saw Lidia as more in tune with the process of change, empowered to resist Giovanni’s assault by her acceptance that their relationship is over (whereas he still clings to this lost love). But in a way, it is Giovanni who embraces change and Lidia who resists it. He will go from being a principled artist to an industrialist’s lackey, from ‘loving’ Lidia to ‘loving’ Valentina, and then back again to Lidia (and so on). Lidia is seeking a sense of continuity between her past, present, and future selves, a sense of agency about the direction her life takes. She wants to reason things out, not be swept along by the impulses of each new moment. Antonioni was preoccupied with the passage of time and its effect on emotions:

[I]t is unbearable to see how, all too often, we throw away all our feelings or we don’t take care of them enough. I mean that as soon as we feel a relationship may be ending, instead of trying to keep it going, we conclude that it is over and look for another.25

Perhaps this goes some way to explaining why he saw a more ‘optimistic’ dimension in the ending of La notte, in Giovanni’s desire to keep the relationship going. But on balance, I think the passage just quoted is more reflective of Lidia’s feelings towards her unfaithful, forgetful, and now violent husband. Giuliana’s angst is a more intense variation on this. She feels things changing and wants Ugo to talk to her about this, so that she can feel secure in her relation to him – in their ability to see, hear, and feel each other – but Ugo, in effect, throws away this disturbed Giuliana and looks for another.

The Rite of Spring, seen through Giuliana’s out-of-focus vision, sums up the effect of the whole sequence. Dova’s challenging work of art has been appropriated to serve a specific function within this controlled domestic environment, like a gear that meshes perfectly with the other decorative items. But for Giuliana, who in this moment finds herself invisible to her husband except as a sex-object, the painting dissolves back into a troubling vision of chaos, like a wall of colourful quicksand that threatens to consume her.

Next: Part 12, Desert spaces.

View the Contents post to browse the full series.

Follow me on BlueSky and/or Twitter.

Novak, Philip, Interpretation and Film Studies (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), p. 75

Baj, Enrico, Two Children in the Nuclear Night (1956). Image from Introvigne, Massimo, ‘Exorcizing the Atomic Bomb Through the Arts. 2. Italy’s Nuclear Art Movement’, Bitter Winter (06 September 2022)

Demori, Lara, ‘Organicize disintegration: from Nuclear Aesthetics to Interplanetary Art’, Palinsesti 7 (2018) pp. 27-57; pp. 32-33

Baj, Enrico, Nuclear Forms (1951). Image from Pierre Menard’s Tumblr.

Demori, Lara, ‘Organicize disintegration: from Nuclear Aesthetics to Interplanetary Art’, Palinsesti 7 (2018) pp. 27-57; p. 34

Fontana, Lucio, Manifesto Blanco (1946), 391.org. I have not yet found an English version of this text with a credited translator.

Tait, Olivia, ‘Lucio Fontana’s Tagli’, Hauser & Wirth, 06 February 2019. The image of Concetto spaziale, Attese (1965) is taken from this article.

Tait, Olivia, ‘Lucio Fontana’s Tagli’, Hauser & Wirth, 06 February 2019.

Fontana, Lucio, Manifesto Blanco (1946), 391.org

Broch, Hermann, The Sleepwalkers, trans. Willa and Edwin Muir, 1947 (New York: Vintage International, 1996), loc. 6955 (Kindle edition)

Antonioni, Michelangelo, and Tonino Guerra, ‘Deserto rosso’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 433-497; p. 442 (my translation)

Antonioni, Michelangelo, Elio Bartolini, and Tonino Guerra, ‘L’avventura’, in Sei film (Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1964), pp. 209-298; p. 287

Cameron, Ian, and Robin Wood, Antonioni (revised edition) (New York: Praeger, 1971), p. 27

Antonioni, Michelangelo, Ennio Flaiano, and Tonino Guerra, ‘La notte’, trans. Roger J. Moore, in Screenplays of Michelangelo Antonioni (London, Souvenir 1963), pp. 209-276; p. 276

Rohdie, Sam, Antonioni (London: British Film Institute, 1990), p. 133

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 65

Arrowsmith, William, Antonioni: The Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 65

Chatman, Seymour, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), pp. 58, 52

Paulicelli, Eugenia, Italian Style: Fashion and Film from Early Cinema to the Digital Age (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), p. 275

‘A Talk with Antonioni on His Work’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 21-47; p. 35

Antonioni admitted to abusing Lucia Bosè during the making of Story of a Love Affair: ‘Oh, how many blows poor Lucia had to take for the final scene! […] To obtain the results I wanted I had to use psychological and physical violence. Insults, scolding, abuses, and hard slaps. In the end, she broke down, crying like a little baby. She played her part wonderfully. […] I hope Lucia has forgiven me. I didn’t like to have to do that, but there was no other way, nor did she have any other technique to rely on’ (Architecture of Vision, pp. 186 and 260). Wim Wenders and some of the actors involved in Beyond the Clouds and ‘The Dangerous Thread of Things’ also expressed discomfort about Antonioni’s approach to the nude scenes and sex scenes in those films (Wenders, My Time With Antonioni, pp. 27, 31-32, 65, 132, 180; Messina, ‘Luisa Ranieri definita la nuova Sophia Loren si racconta: “Sono una timida…”’, Novella 2000, 13 February 2018.

‘A Talk with Antonioni on His Work’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 21-47; p. 39

Vaccari, Luigi, ‘Profession Against’, in The Architecture of Vision, ed. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi; American edition by Marga Cottino-Jones (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), pp. 217-225; p. 223